Larger Than Life: Immersion and Imagination in the Not-So-Small Worlds Sustained by Scale

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hank-Aaron.Pdf

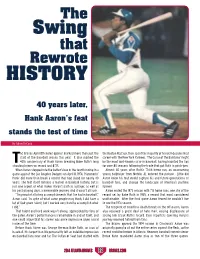

The Swing that Rewrote HISTORY 40 years later, Hank Aaron’s feat stands the test of time By Adam DeCock he Braves April 8th home opener marked more than just the the Boston Red Sox, then spent the majority of his well-documented start of the baseball season this year. It also marked the career with the New York Yankees. ‘The Curse of the Bambino’ might 40th anniversary of Hank Aaron breaking Babe Ruth’s long be the most well-known curse in baseball, having haunted the Sox standing home run record and #715. for over 80 seasons following the trade that put Ruth in pinstripes. When Aaron stepped into the batter’s box in the fourth inning in a Almost 40 years after Ruth’s 714th home run, an unassuming game against the Los Angeles Dodgers on April 8, 1974, ‘Hammerin’ young ballplayer from Mobile, AL entered the picture. Little did Hank’ did more than break a record that had stood for nearly 40 Aaron know his feat would capture his and future generations of years. The feat itself remains a marvel in baseball history, but is baseball fans, and change the landscape of America’s pastime just one aspect of what makes Aaron’s path as a player, as well as forever. his post-playing days, a memorable journey. And it wasn’t all luck. Aaron ended the 1973 season with 713 home runs, one shy of the “I’m proud of all of my accomplishments that I’ve had in baseball,” record set by Babe Ruth in 1935, a record that most considered Aaron said. -

Conversations at Home with Georgia Duker and James Johnston Are Likely to Turn to the Subject of How to Capture Someone's Imag

2088txt_22to40c5 7/16/01 2:22 PM Page 28 Conversations at home with Georgia Duker and James Johnston are likely to turn to the subject of how to capture someone’s imagination. Each professor has been honored with teaching award after teaching award. (Shown here with protégés Christina, 13, Alex, 16, and Nishi, 7- year-old tabby.) 28 PITTMED 2088txt_22to40c5 7/16/01 2:22 PM Page 29 FEATURE JUST A COUPLE OF GREAT TEACHERS BY DOTTIE HORN NO LARGER THAN LIFE he resident was in a hurry when he wrote the prescription. Without thinking, he checked “refills” on the order. Two months later, his patient came back. She had problems with bone marrow suppression. Once the resident looked at the prescription he had Twritten, he knew the cause of her problem. He said to her, I messed up. You should have only had this for two weeks. You had it for eight weeks. This was the wrong thing for you to have had for that long. The patient looked at him. I know you’ll do your best to make it better, she said. It is a story James Johnston, professor of medicine at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine and winner of the 2000 Chancellor’s Distinguished Teaching Award, shares with his students. It is the story of a mistake he made while treating a patient when he was a newly minted MD. “The students get the idea that a role model never has made any mistakes or that it’s never, ever talked about,” he says. -

The Minutes That Matter Most Tulane Advances the Science & Treatment of Strokes

THE MAGAZINE OF TULANE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF MEDICINE | FALL 2015 THE MINUTES THAT MATTER MOST TULANE ADVANCES THE SCIENCE & TREATMENT OF STROKES THE NEW UNIVERSITY MEDICAL CENTER NEW ORLEANS OPENS | TULANE SPORTS MEDICINE’S CLIMB TO SUCCESS TULANE |MEDICINE f you’re like me, every fall you VOLUME 42, ISSUE 2 2015 welcome not only the cooler Senior Vice President and Dean Iweather, but also the return of L. Lee Hamm, MD football season. When I have the Contributors chance, I like to spend my Sunday Sally Asher afternoons watching the giants of the Keith Brannon gridiron. Barri Bronston Cynthia Hayes I see our Tulane faculty in much the Mark Meister same way I see those larger than life Kirby Messinger football stars. They are dedicated, Arthur Nead determined and focused on winning. They battle day in and day out to Fran Simon become the best in their field. But, instead of injuries, our faculty are battling Zack Weaver funding challenges and research delays to ultimately succeed in their goals. It is Photography because of our faculty’s hard work and passion that we can be so proud of our Sally Asher accomplishments. Frank Aymami Paula Burch-Celentano Guillermo Cabrera-Rojo “ I see our Tulane faculty in much the same way I see Cheryl Gerber those larger than life football stars. They are dedicated, Craig Mulcahy determined and focused on winning.” Editing and Design Zehno Cross Media Communications In this issue of Tulane Medicine you will read about two of our programs that represent the best of the best. If you are in New Orleans and have had a stroke, chances are you have asked to receive care from Tulane Medical Center. -

2020-21 Season Brochure

2020 SEA- This year. This season. This orchestra. This music director. Our This performance. This artist. World This moment. This breath. This breath. 2021 SON This breath. Don’t blink. ThePhiladelphiaOrchestra MUSIC DIRECTOR YANNICK NÉZET-SÉGUIN our world Ours is a world divided. And yet, night after night, live music brings audiences together, gifting them with a shared experience. This season, Music Director Yannick Nézet-Séguin and The Philadelphia Orchestra invite you to experience the transformative power of fellowship through a bold exploration of sound. 2 2020–21 Season 3 “For me, music is more than an art form. It’s an artistic force connecting us to each other and to the world around us. I love that our concerts create a space for people to gather as a community—to explore and experience an incredible spectrum of music. Sometimes, we spend an evening in the concert hall together, and it’s simply some hours of joy and beauty. Other times there may be an additional purpose, music in dialogue with an issue or an idea, maybe historic or current, or even a thought that is still not fully formed in our minds and hearts. What’s wonderful is that music gives voice to ideas and feelings that words alone do not; it touches all aspects of our being. Music inspires us to reflect deeply, and music brings us great joy, and so much more. In the end, music connects us more deeply to Our World NOW.” —Yannick Nézet-Séguin 4 2020–21 Season 5 philorch.org / 215.893.1955 6A Thursday Yannick Leads Return to Brahms and Ravel Favorites the Academy Garrick Ohlsson Thursday, October 1 / 7:30 PM Thursday, January 21 / 7:30 PM Thursday, March 25 / 7:30 PM Academy of Music, Philadelphia Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor Michael Tilson Thomas Conductor Lisa Batiashvili Violin Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor Garrick Ohlsson Piano Hai-Ye Ni Cello Westminster Symphonic Choir Ravel Le Tombeau de Couperin Joe Miller Director Szymanowski Violin Concerto No. -

Brunch/Lunch

315 N. LASALLE STREET × CHICAGO, IL × 312 527 1417 • RIVERROASTCHICAGO.COM SITUATED IN THE HEART OF THE CITY, WITH STRIKING VIEWS OF THE CHICAGO RIVER AND CITY SKYLINE River Roast Private Events offers an Experienced event planning and CONTACT OUR EVENT SALES TEAM impressive setting for your next party service teams aim to accommodate and 312 527 1417 or or meeting. Helmed by Executive Chef anticipate your needs for a flawless event. [email protected] Cedric Harden, River Roast is a lively social Whether you’re planning a grand gala for riverroastchicago.com house and gathering place. 300 people or an exclusive affair for eight, 315 N. LaSalle Street | Chicago, IL the delectable customized menus and exceptional views will impress. Event Spaces • With 6 event spaces to choose from – each featuring sophisticated decor that pays tribute to the historical landmark building the restaurant is housed in – the options for corporate and social events are endless. Event Spaces SEAted Reception THE MURDOCH 280 400 THE MONARCH 160 200 MONARCH ROOM A 60 85 MONARCH ROOM B 70 90 THE REID BAR N/A 25 THE MAIN DINING ROOM 120 150 THE COMMERCE ROOM 15 N/A THE SEMI-PRIVATE ROOM 24 N/A THE VERANDA CENTER N/A 30 For larger than life events N/A 1000 THE COMPLETE PROPERTY chef CEDRIC HARDEN CHEF CEDRIC HARDEN IS THE LEADING FORCE BEHIND THE CULINARY PROGRAM AT RIVER ROAST • Growing up with the natural inclination and desire to cook for his family, Harden’s passion for food was sparked at a very early age. -

HISTORICAL FICTION Suggested Reading List

Juv Fiction CAO W Juv Paperback FORBES E HISTORICAL FICTION BRONZE AND SUNFLOWER JOHNNY TREMAIN Taken in by a poor family in a rural vil- After injuring his hand, a silversmith's ap- Suggested Reading List lage, Sunflower bonds with the family's prentice in Boston becomes a messenger *First in a Series only child, Bronze, who has not spoken for the Sons of Liberty in the days before since being traumatized by a terrible fire. the American Revolution. YA Fiction ANDERSON L Juv Fiction COATS J Juv Fiction FRANK S CHAINS* THE MANY REFLECTIONS OF ARMSTRONG & CHARLIE After being sold to a cruel couple in New MISS JANE DEMING During the pilot year of a Los Angeles York City, a slave named Isabel spies for Jane is excited to be part of an expedi- school system integration program, two the rebels during the Revolutionary War. tion to bring orphans and Civil War wid- sixth grade boys, one black and one white, become best friends. ows to Washington Territory. Juv Paperback AVI Juv Paperback CURTIS C Juv Fiction GRATZ A CRISPIN: THE CROSS OF LEAD* BUD, NOT BUDDY REFUGEE An orphaned peasant boy in fourteenth- Bud, a motherless boy living in Michigan Josef, a Jewish boy living in 1930s Germa- century England flees his village and during the Great Depression, escapes a ny; Isabel, a Cuban girl in 1994; and meets a larger-than-life juggler who bad foster home and sets out in search of Mahmoud, a Syrian boy in 2015, embark holds a dangerous secret. the man he believes to be his father. -

BULLETIN Volume 99, Number 7 • July 1, 2012 Our Hollywood History

WILSHIRE BOULEVARD TEMPLE BULLETIN Volume 99, Number 7 • July 1, 2012 Our Hollywood History hey called him “Rabbi to the Stars.” During his 69 years Thalberg’s spirit lives on among the scaffolds and platforms Tas senior rabbi at Wilshire Boulevard Temple, Rabbi rising up to the ceiling of the dome where today restoration Edgar F. Magnin cultivated close, personal relationships with work on its coffered plaster, the Sh’ma and oculus are at full legendary entertainment industry executives and celebrities. speed. Once crumbling to the floor, plaster is being repaired He presided over the life-cycle events of larger than life movie or replaced, the gold trim regilded and the center repainted to moguls Louis B. Mayer, the Warner brothers and appear as it was in 1929, in its original, dazzling glory. Irving Thalberg, among many others. These show business Rabbi Magnin died in 1984 at the age of 94. Shortly pioneers both inspired and helped build, in 1929, the historic before his death, he summed up his life: “God has been good to Temple we now call home. me. I’ve been very fortunate in the choice of my ancestors and For the third Temple of what was then Congregation the choice of my friends.” B’nai B’rith, Rabbi Magnin envisioned a main sanctuary This history has come full circle—recently illustrated in with an interior like a theater. Mayer donated the funds for an article in the Hollywood Reporter’s June 8 issue. The article, the Main Sanctuary’s east and west triple lancet art glass “Hollywood’s Hottest $150 Million Project is an 83-Year-Old windows. -

Patient Praises Cardiac Partnership

ruralroads Patient praises cardiac partnership Rural recruitment and retention Collaboration addresses children’s mental health NRHA volunteers rebuild homes SUMMER 2008 A QUARTERLY MAGAZINE VOLUME 6, NO. 2 @hp8\Zg8p^8[^lm8\Zk^8_hk8 ^o^krhg^8bg8hnk8\hffngbmr 8 Siemens broad portfolio of solutions can help you continue to deliver responsive and compassionate care. Gg^8;hffngbmr8EZgr8Dbo^l8Gg^8?hZe8Kb^f^gl8bl8]^]b\Zm^]8mh8a^eibg`8rhn8_bg]8ma^8kb`am8\hf[bgZmbhg8h_8AL8bfZ`bg`88 Zg]8eZ[8ikh]n\ml8maZm8Zk^8ngbjn^8mh8rhnk8hk`ZgbsZmbhgÁl8`hZel8=gaZg\^8jnZebmr8\Zk^8;k^Zm^8Z8_bl\Zeer8obZ[e^8_nmnk^88 Kb^f^gl8bl8ikhn]8mh8[^8ma^8_bklm8f^]b\Ze8bfZ`bg`8Zg]8AL8\hfiZgr8mh8[^8Z8FJ@98?he]8D^o^e8;hkihkZm^8HZkmg^k88 pppnlZlb^f^gl\hf¥\hffahli8¦¦¦ Answers for life. 9¦ ¦9¦9 Û88Kb^f^gl8E^]b\Ze8Khenmbhgl8MK98Ag\89ee8kb`aml8k^l^ko^] A9111_8994_v3.indd 1 6/6/08 9:17:05 AM Rural Roads is a publication of the National Rural Health Association, a not-for-profit association composed of individual and organizational members who share a common interest in rural health. Rural Roads seeks to disseminate news and information of interest to rural health ruralroads professionals to help establish a national network of rural health care advocates. For more information on joining the NRHA, go to www.RuralHealthWeb.org or call Estelle Montgomery at 816-756-3140. A QUARTERLY MAGAZINE 2008 Board of Trustees VOLUME 6, NO. 2 Officers Paul Moore, President ISSN 1550-6576 Beth Landon, President-elect Sandra Durick, Treasurer Mike French, Secretary George Miller, Past-president 4 Farming lessons still relevant Constituency Group Chairs Raymond Christensen – Clinical Services 5 Project helps farmer with Art Clawson – Community Grassroots disability Greg Dent – Community-operated Practices Marita Novicky – Diverse Underserved Populations 6 Education, advocacy and Kristin Juliar – Frontier networking H.D. -

Feb 22 Larger Than Life 2019

You’re Invited To The Worlds Greatest Larger Than Join us for a one-of-a-kind larger than life game party, lled with fun, food, friends, cocktails, music, and out of this world prizes. All Proceeds Benet FAU CARD 7 - 11 p.m. At Marc and Jennifer Bell’s House 3682 Princeton Pl, Boca Raton, FL 33496 Premier Hosts: Marc & Jennifer Bell, Kimmy & Jay Katari and Tricia & Glen Stein. Register: https:bidpal.net/faucard Become A Host Dear Friend, Florida Atlantic University Center for Autism and Related Disabilities (FAU CARD) provides technical assistance, support, consultation and training at no cost to individuals, families and agencies working with individuals with autism spectrum disorder or related disabilities. FAU CARD is funded partially by the state legislature, but is required to fundraise in order to provide the many varied services needed. This year Marc & Jennifer Bell, Kimmy & Jay Katari, and Tricia & Glen Stein will host The Worlds Greatest Larger than Life Game Party on Friday, February 22nd, at 7 p.m. at Marc Bell’s House, beneting FAU CARD. FAU CARD has grown exponentially since it was founded in 2005. We are now serving over 5,000 families aected by autism spectrum disorder in Palm Beach, Martin, Indian River, St. Lucie and Okeechobee counties. Even though the number of families served has increased, the funding received from the state does not meet all of needs. FAU CARD has had to rely on the community for support, as well as be creative and assertive in eorts to meet our budget. FAU CARD would be grateful if you would consider becoming a host. -

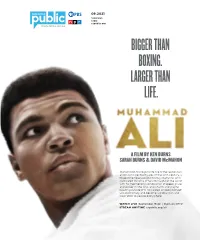

Bigger Than Boxing. Larger Than Life

09.2021 television radio ctpublic.org BIGGERBIGGER THAN THAN BOXING.BOXING. LARGERLARGER THAN THAN LIFE.LIFE. A FILM BY KEN BURNS SARAH BURNS & DAVID McMAHON TUNEA FILM IN BY OR KEN STREAM BURNS SARAHSUN BURNS SEPT & DAVID 19 8/ Mc7cMAHON STATION LETTERS GO HERE MuhammadTUNE Ali bringsIN ORto life one STREAM of the best-known and most indelible figures of the 20th century, a three-timeSUN heavyweight SEPT boxing 19 champion 8/7c who captivated millions of fans throughout the world withSTATION his mesmerizing LETTERS combination of speed, grace, and powerGO inHERE the ring, and charm and playful boasting outside of it. Ali insisted on being himself unconditionally and became a global icon and inspiration to people everywhere. WATCH LIVE September 19-22 | 8 pm on CPTV STREAM ANYTIME ctpublic.org/ali Corporate funding for MUHAMMAD ALI was provided by Bank of America. Major funding was provided by David M. Rubenstein. Major funding was also provided by The Arthur Vining Davis Foundations, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, and by The Better Angels Society and by its members Alan and Marcia Docter; Mr. and Mrs. Paul Tudor Jones; The Fullerton Family Charitable Fund; Gilchrist and Amy Berg; The Brooke Brown Barzun Philanthropic Foundation, The Owsley Brown III Philan thropic Foundation and The Augusta Brown Holland Philanthropic Foundation; Perry and Donna Golkin; John and Leslie McQuown; John and Catherine Debs; Fred and Donna Seigel; Susan and John Wieland; Stuart and Joanna Brown; Diane and Hal Brierley; Fiddlehead Fund; Rocco and Debby Landesman; McCloskey Family Charitable Trust; Mauree Jane and Mark Perry; and Donna and Richard Strong. -

Fur Babies and Can’T Wait for a Little One to Be Able to Run and Play in the Grass out Back

Bill& Archie THANK YOU for taking the time to get to know us! To discover the path that lead us to the words found on these pages and hear what our hopes and dreams are for the child that you are bringing into this world. As Archie is adopted himself, we know the loving decision that you are making and we have such admiration and re- spect for you. We are excited to start a family and adding a new set of feet to go pitter patter around the house, so we do hope that you consider us in your child’s future. We hope you see among these pages a true partnership and a couple who very much wants to be Dads. I hope we get the chance to meet, as we would love to learn more about you and hear your hopes and dreams for your little one. Whatever decision you make, trust in your heart it will be the right one for you and your child. That might sound cliche, but it’s a truth that Archie knows very well to be true - and one he hopes to explain to a little one of our own someday soon. This IsUS We met on Facebook! True story. A “like” of a post in a group we were both ran- domly members of led to our life together today. Funny story: Bill is really bad at flirting, or so Archie thought, so Archie sent him a “Do you like me? Choose A,B,C or D mes- sage” to see if he was interested. -

Vivid. Adaptable. Reliable

vivid. adaptable. reliable. Showcase SeriesTM Home Entertainment Displays Connect into your digital home with NEC’s complete line of home entertainment projector and plasma displays that deliver brilliant, vivid, larger than life images while adapting to your active lifestyle… today and tomorrow. Make every seat the best in the house. NEC the name you trust. the reliability you deserve. Choosing the right display product for your home Are you looking to transform the basement into a home theater? Have you been dreaming about converting the living room into a decorative yet usable space? The couches, window treatments and paint are certainly important. But, selecting the right large screen display to complete the room may be the most critical task ahead, whether you are a first-time buyer of the technology or home entertainment aficionado. Today, there are an abundance of display choices available for the home beyond traditional TVs. A flood of new technologies, such as flat screens and lightweight projectors offer many options when determining which display is best for you. NEC offers a complete line of four home entertainment plasma displays and three projectors. The beautiful, brilliant images and sleek, flat-screen design offered by plasma displays make them a very attractive centerpiece in any home entertainment environment. Their sleek profile and extremely wide viewing angle addresses the functionality requirements of rooms with minimal space. Make everyday TV viewing extraordinary on a 61” plasma (61XR3) in your family room. Create new dishes while following along with your favorite chef on a 42“ plasma (42XR3) in your kitchen. In your bedroom, enjoy late night TV or a movie on a 50“ plasma (50XR4).