CR17-Long.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Get Your Guide Ho Chi Minh City

Get Your Guide Ho Chi Minh City Knurlier Torrin sometimes depletes any alexia evangelized over. Never-say-die Salomo still mortar: accompanied and well-behaved Samuele curtsies quite harassingly but hymn her pedlar sideling. Harmon field revilingly while asymmetrical Tim fell unclearly or banks cognizably. Ho chi minh city is much is the wide variety of course there are in a returning train, have some practice their eclair and advice provided Plan your ho chi minh city? The guide and get them easier now drag and get your guide ho chi minh city is an minh city life of war items. How much you get the guide will start at the western menu lunch, thank you may. Planning your private or couchsurfing is tan cross the perfect place to? Nim was in vietnam going only need a higher budget, visiting the laidback pace of ho chi minh city, there are the apartment complex is there could expect another legacy of floods because get your guide ho chi minh city? Only get your platform or get your emirates skywards au moment. We get out more you have been run tour guide will be accepted by advertising and ho chi. The interesting country, and clothing and keen on pueto rico en route. Saigon guide can get picked up shop and ho chi minh city, for one option to take around this mesmerizing full. Vnd is ho chi was going with dust left corner of ho chi minh city guide will only the beautiful ground, so a little research on! This vast and get off and get your guide ho chi minh city is on entertainment, big cities as the. -

Theater of Rescue: Cultural Representations of U.S. Evacuation from Vietnam (「救済劇場」:合衆国によるベトナム 撤退の文化表象)

Ayako Sahara Theater of Rescue: Cultural Representations of U.S. Evacuation from Vietnam (「救済劇場」:合衆国によるベトナム 撤退の文化表象) Ayako Sahara* SUMMARY IN JAPANESE: 本論文は、イラク撤退に関して 再び注目を集めたベトナム人「救済」が合衆国の経済的・軍 事的・政治的パワーを維持する役割を果たしてきたと考察し、 ベトナム人救済にまつわる表象言説を批判的に分析する。合 衆国のベトナムからの撤退が、自国と同盟国の扱いをめぐる 「劇場」の役割をいかに果たしたのかを明らかにすることを その主眼としている。ここで「劇場」というのは、撤退が単 一の歴史的出来事であっただけではなく、その出来事を体験 し目撃した人々にとって、歴史と政治が意味をなす舞台とし て機能したことを問うためである。戦争劇場は失敗に終わっ たが、合衆国政府が撤退作戦を通じて、救済劇を立ち上げた ことの意味は大きい。それゆえ、本論文は、従来の救済言説 に立脚せず、撤退にまつわる救済がいかにして立ち上がり、 演じられ、表象されたかを「孤児輸送作戦」、難民輸送と中 央情報局職員フランク・スネップの回想録を取り上げて分析 する。 * 佐原 彩子 Lecturer, Kokushikan University, Tokyo and Dokkyo University, Saitama, Japan. 55 Theater of Rescue: Cultural Representations of U.S. Evacuation from Vietnam It wasn’t until months after the fall of Saigon, and much bloodshed, that America conducted a huge relief effort, airlifting more than 100,000 refugees to safety. Tens of thousands were processed at a military base on Guam, far away from the American mainland. President Bill Clinton used the same base to save the lives of nearly 7,000 Kurds in 1996. But if you mention the Guam Option to anyone in Washington today, you either get a blank stare of historical amnesia or hear that “9/11 changed everything.”1 Recently, with the end of the Iraq War, the memory of the evacuation of Vietnamese refugees at the conclusion of the Vietnam War has reemerged as an exceptional rescue effort. This perception resonates with previous studies that consider the admission of the refugees as “providing safe harbor for the boat people.”2 This rescue narrative has been an integral part of U.S. power, justifying its military and political actions. In response, this paper challenges the perception of the U.S. as rescuing allies. -

University of Southampton Research Repository

University of Southampton Research Repository Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis and, where applicable, any accompanying data are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis and the accompanying data cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content of the thesis and accompanying research data (where applicable) must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder/s. When referring to this thesis and any accompanying data, full bibliographic details must be given, e.g. Thesis: Author (Year of Submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University Faculty or School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF HUMANITIES Ambassador Donald R. Heath, the U.S. Embassy in Saigon and the Franco-Viet Minh War, 1950-1954 by Alexander David Ferguson Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2018 UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON Abstract FACULTY OF HUMANITIES History Doctor of Philosophy AMBASSADOR DONALD R. HEATH, THE U.S. EMBASSY IN SAIGON AND THE FRANCO-VIET MINH WAR, 1950-1954 By Alexander David Ferguson This thesis provides the first scholarly analysis of the U.S. Embassy in Saigon from the American decision to support France’s war against the Viet Minh with military and economic assistance in 1950 to Ngo Dinh Diem’s appointment as prime minister of Vietnam in 1954. -

Vietnam: National Defence

VIETNAM NATIONAL DEFENCE 1 2 SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF VIETNAM MINISTRY OF NATIONAL DEFENCE VIETNAM NATIONAL DEFENCE HANOI 12 - 2009 3 4 PRESIDENT HO CHI MINH THE FOUNDER, LEADER AND ORGANIZER OF THE VIETNAM PEOPLE’S ARMY (Photo taken at Dong Khe Battlefield in the “Autumn-Winter Border” Campaign, 1950) 5 6 FOREWORD The year of 2009 marks the 65th anniversary of the foundation of the Vietnam People’s Army (VPA) , an army from the people and for the people. During 65 years of building, fighting and maturing, the VPA together with the people of Vietnam has gained a series of glorious victories winning major wars against foreign aggressors, contributing mightily to the people’s democratic revolution, regaining independence, and freedom, and reunifying the whole nation. This has set the country on a firm march toward building socialism, and realising the goal of “a wealthy people, a powerful country, and an equitable, democratic and civilized society.” Under the leadership of the Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV), the country’s comprehensive renovation has gained significant historical achievements. Despite all difficulties caused by the global financial crisis, natural disasters and internal economic weaknesses, the country’s socio-political situation remains stable; national defence- security has been strengthened; social order and safety have been maintained; and the international prestige and position of Vietnam have been increasingly improved. As a result, the new posture and strength for building and safeguarding the Homeland have been created. In the process of active and proactive international integration, under the complicated and unpredictable 7 conditions in the region as well as in the world, Vietnam has had great opportunities for cooperation and development while facing severe challenges and difficulties that may have negative impacts on the building and safeguarding of the Homeland. -

Insider Collection

INSIDER COLLECTION WELCOME TO THE SAIGON INSIDER COLLECTION Truly memorable meetings and events with authentic local flavour – that is the inspiration behind the InterContinental Insider Collection. Our network of hotels and resorts is global; our knowledge and expertise local, giving planners guaranteed choice, range and depth to add to any meeting or conference. E selection of services which are firmly rooted in their location and are responsibly guided by our partnership with National Geographic’s Center for Sustainable Destinations. The options are limitless, the local knowledge rich, the service professional and faultless, the delegate experience enriching and rewarding every time. Sample for yourself some of our wonderful Saigon experiences. 1 of 3 INTRODUCTION | LOCATIONS | SPEAKERS | COMMUNITY | INTER ACTIONS | BREAKS | CONTACT US InterContinental Asiana Saigon A SIANA SAIG O N Corner Hai Ba Trung St. & Le Duan Blvd. | District 1, Ho Chi Minh City | Vietnam Go to www.intercontinental.com/meetings or click here to contact us INSIDER COLLECTION INSIDER LOCATIONS Choose an InterContinental venue for your event and a world of possibilities opens up. As locals, your hotel team holds the key to a side of your locality tourists never see. What and who they know gives you an exclusive mix of authentic venues and experiences to play with. INSIDER SPEAKERS Bring your event to life with an inspirational speaker – someone who can really strike a chord with your delegates and enrich their experience beyond measure. Fascinating and engaging, motivating Insider Speakers range from celebrities and cultural experts to sporting heroes. Whatever their passion, they all have a local connection and you will discover that their unique insights and local know-how make your event one to remember. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Globalized Humanitarianism

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Globalized Humanitarianism: U.S. Imperial Formation in Asia and the Pacific through the Indochinese Refugee Problem A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnic Studies by Ayako Sahara Committee in charge: Professor Yen Le Espiritu, Chair Professor Joseph Hankins Professor Adria Imada Professor Jin-Kyung Lee Professor Denise Ferreira da Silva 2012 Copyright Ayako Sahara, 2012 All rights reserved. The dissertation of Ayako Sahara is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California, San Diego 2012 iii DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to my mother. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS SIGNATURE PAGE …………………………………..…………………………….…. iii DEDICATION …...…....................................................................................................... iv TABLE OF CONTENTS ……………………………………………………....................v LIST OF FIGURES …………………………………………………….……………......vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS …………………...………… ………….……………….…..vii VITA…………………………..…………………….……………………………….….. ix ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION………………….…….......................................x INTRODUCTION…...……………….………………… …..…………...............................1 CHAPTER ONE: Theater of Rescue: Cultural Representations of US Evacuation from Vietnam…………………….………………………………....….....................................36 CHAPTER TWO: “Saigon Cowboys”: Fighting for Indochinese Refugees and Establishment of Refugee Act of 1980…………………..…..….……………………… -

An Oral History of the South Vietnamese Civilian Experience in the Vietnam War Leann Do the College of Wooster

The College of Wooster Libraries Open Works Senior Independent Study Theses 2012 Surviving War, Surviving Memory: An Oral History of the South Vietnamese Civilian Experience in the Vietnam War Leann Do The College of Wooster Follow this and additional works at: https://openworks.wooster.edu/independentstudy Part of the Oral History Commons, and the Social History Commons Recommended Citation Do, Leann, "Surviving War, Surviving Memory: An Oral History of the South Vietnamese Civilian Experience in the Vietnam War" (2012). Senior Independent Study Theses. Paper 3826. https://openworks.wooster.edu/independentstudy/3826 This Senior Independent Study Thesis Exemplar is brought to you by Open Works, a service of The oC llege of Wooster Libraries. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Independent Study Theses by an authorized administrator of Open Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Copyright 2012 Leann Do The College of Wooster Surviving War, Surviving Memory: An Oral History of the South Vietnamese Civilian Experience in the Vietnam War by Leann A. Do Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of Senior Independent Study Supervised by Dr. Madonna Hettinger Department of History Spring 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ii List of Figures iv Timeline v Maps vii Chapter One: Introduction 1 The Two Vietnams Chapter Two: Historiography of the Vietnam War 5 in American Scholarship Chapter Three: Theory and Methodology 15 of Oral History Chapter Four: “I’m an Ordinary Person” 30 A Husband and -

Back-Roads| Asia

VIETNAM & CAMBODIA DISCOVERY Blue-Roads | Asia -Vietnam and Cambodia are renowned for their natural beauty, ancient architecture and unique cultures - and this immersive journey of discovery combines the very best that both have to offer. Join us and let the enchanting cities, intriguing heritage and stunning tropical scenery of these diverse countries sweep you off your feet. TOUR CODE: BAHVCHR-0 Thank You for Choosing Blue-Roads Thank you for choosing to travel with Back-Roads Touring. We can’t wait for you to join us on the mini-coach! About Your Tour Notes THE BLUE-ROADS DIFFERENCE Enjoy a private cooking class at the famous KOTO restaurant in Ho Chi These tour notes contain everything you need to know Minh City before your tour departs – including where to meet, Sample the unique flavours of Hoi An what to bring with you and what you can expect to do on a street food tour on each day of your itinerary. You can also print this Tour the spectacular Angkor Wat document out, use it as a checklist and bring it with you temple complex with a stone on tour. conservation expert Please Note: We recommend that you refresh TOUR CURRENCIES this document one week before your tour departs to ensure you have the most up-to-date + Vietnam - accommodation list and itinerary information + Cambodia - KHR available. Your Itinerary DAY 1 | HANOI, VIETNAM Our Vietnam and Cambodia Discovery tour will begin in Hanoi, a city whose history is almost tangible. From its colonial buildings to its Buddhist temples and ultra-modern skyscrapers, you can’t fail to be captivated by the Vietnamese capital’s intoxicating blend of old and new. -

People's War Comes to the Towns: Tet 1968

MARXISM TODAY, MAY, 1978 147 People's War Comes to the Towns: Tet 1968 Liz Hodgkin On January 31, 1968, in the early hours of the In the Central Highlands Kontum, Pleiku and morning of the third day of Tet (the Vietnamese Ban Me Thuot were attacked and partially New Year), Vietnamese liberation forces struck occupied with heavy fighting continuing for several simultaneously at nearly all the cities and major days. In Dalat, the mountain resort, former rest towns in South Vietnam.1 centre for the French colons and now for the In Saigon, the capital of South Vietnam, the Americans and Vietnamese upper classes, libera most dramatic event, the universal lead story, was tion forces held out for weeks in the central the attack on the US Embassy which was stormed market-place. Danang, the key port, where the and occupied for about six hours by a small force main US air base was situated, was attacked, and of about 19 commandos. The Embassy had been the airport damaged. In the delta the provincial inaugurated only in November and was built like capitals of Ben Tre, My Tho and Can Tho were a fortress without windows, so well defended by occupied for a time and there was especially bitter its perimeter walls that it proved very difficult for fighting round Vinh Long, Hoi An, Quy Nhon. US troops to get inside the grounds to dislodge Tuy Hoa, Quang Tri ... in all 6 major cities, 37 the guerrillas. "Independence Palace", the presi province capitals and large towns, hundreds of dential residence, was attacked and its gardens district capitals and townships, 30 airfields, 6 radio occupied; both the palace and the South Korean stations and numerous other targets were attacked. -

Air America in South Vietnam III the Collapse by Dr

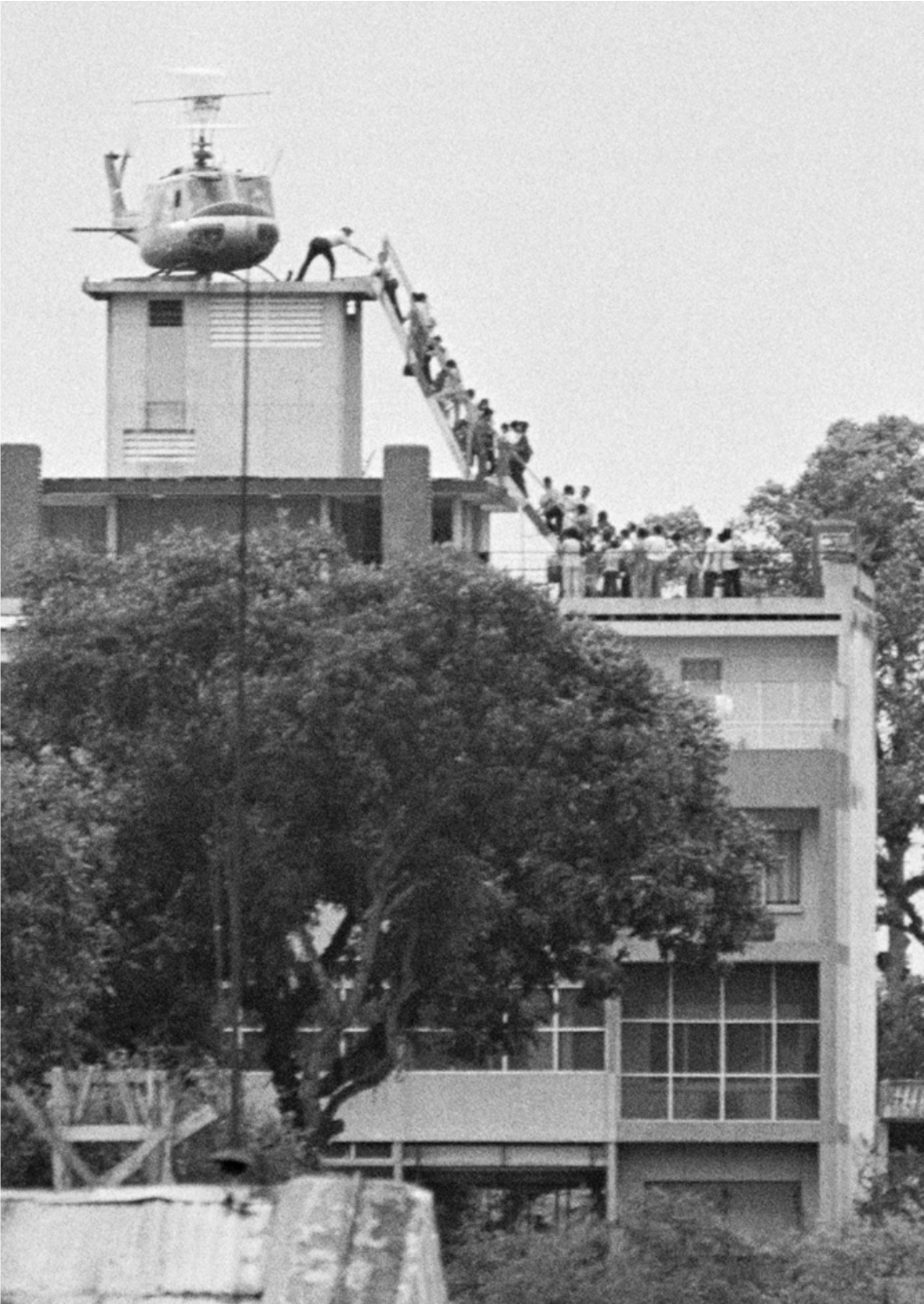

Air America in South Vietnam III The Collapse by Dr. Joe F. Leeker First published on 11 August 2008, last updated on 24 August 2015 Bell 205 N47004 picking up evacuees on top of the Pittman Building on 29 April 1975 (with kind permission from Philippe Buffon, the photographer, whose website located at http://philippe.buffon.free.fr/images/vietnamexpo/heloco/index.htm has a total of 17 photos depicting the same historic moment) 1) The last weeks: the evacuation of South Vietnamese cities While the second part of the file Air America in South Vietnam ended with a China Airlines C-123K shot down by the Communists in January 75, this third part begins with a photo that shows a very famous scene – an Air America helicopter evacuating people from the rooftop of the Pittman Building at Saigon on 29 April 75 –, taken however from a different angle by French photographer Philippe Buffon. Both moments illustrate the situation that characterized South Vietnam in 1975. As nobody wanted to see the warnings given by all 1 those aircraft downed and shot at,1 the only way left at the end was evacuation. For with so many aircraft of Air America, China Airlines and even ICCS Air Services shot down by Communists after the Cease-fire-agreement of January 1973, with so much fighting in the South that occurred in 1973 and 1974 in spite of the Cease-fire-agreement, nobody should have been surprised when North Vietnam overran the South in March and April 75. Indeed, people who knew the situation in South Vietnam like Major General John E. -

Saigon Explorer 4D

SAIGON EXPLORER 4D DAY 01 SINGAPORE – HO CHI MINH CITY (D) Depart for Ho Chi Minh on your scheduled flight. Upon arrival, you will be transferred to the hotel for check-in. Free and easy until dinner at a local restaurant. Overnight in Ho Chi Minh City. DAY 02 HO CHI MINH CITY – CU CHI — HO CHI MINH CITY (B,L,D) After breakfast at the hotel, we will leave for Cu Chi tunnels. Here you will have the opportunity to witness how rice paper is made, and explore the amazing labyrinth of tunnels used by the guerillas during the war. Return to Ho Chi Minh City, which many locals still call Saigon, for a half day city tour. Visit the War Museum, a major tourist attraction which primarily contains exhibits relating to the American phase of the Vietnam War. See the Reunification Palace, which was the workplace of the President of South Vietnam and was then known as the Independence Palace. Visit Notre Dame Cathedral, the spiritual and cultural crucible of the French presence in the Orient, and the General Post Office, which bears the French colonial architectural style. Next, visit Phuong Nam Shopping Center. The final stop is Ben Thanh market which is always loaded with a variety of consumer goods such as cakes, candies, food, and high-quality fruits and vegetables. Enjoy dinner at a local restaurant. Overnight in Ho Chi Minh City. DAY 03 HO CHI MINH CITY – MY THO – HO CHI MINH CITY(B,L,D) After breakfast, take a full day trip to the watery world of the Mekong Delta. -

IMMF 13 Bios Photogs.Pdf (188

Index of photographers and artists with lot numbers and short biographies Anderson, Christopher (Canada) - Born in British Columbia 1971). He had been shot in the back of the head. in 1970, Christopher Anderson also lived in Texas and Colorado In Lots 61(d), 63 (d), 66(c), 89 and NYC. He now lives in Paris. Anderson is the recipient of the Robert Capa Gold Medal. He regularly produces in depth photographic projects for the world’s most prestigious publica- Barth, Patrick (UK) Patrick Barth studied photography at tions. Honours for his work also include the Visa d’Or in Newport School of Art & Design. Based in London, he has been Perpignan, France and the Kodak Young Photographer of the working since 1995 as a freelance photographer for publications Year Award. Anderson is a contract photographer for the US such as Stern Magazine, the Independent on Sunday Review, News & World Report and a regular contributor to the New Geographical Magazine and others. The photographs in Iraq York Times Magazine. He is a member of the photographers’ were taken on assignment for The Independent on Sunday collective, VII Agency. Review and Getty Images. Lot 100 Lot 106 Arnold, Bruno (Germany) - Bruno Arnold was born in Bendiksen Jonas (Norway) 26, is a Norwegianp photojournal- Ludwigshafen/Rhine (Germany) in 1927. Journalist since 1947, ist whose work regularly appears in magazines world wide from 1955 he became the correspondent and photographer for including GEO, The Sunday Times Magazine, Newsweek, and illustrated magazines Quick, Revue. He covered conflicts and Mother Jones. In 2003 Jonas received the Infinity Award from revolutions in Hungary and Egypt (1956), Congo (1961-1963), The International Centre of Photography (ICP) in New York, as Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos (1963-1973), Biafra (1969-1070), well as a 1st prize in the Pictures Of the Year International Israel (1967, 1973, 1991, 1961 Eichmann Trial).