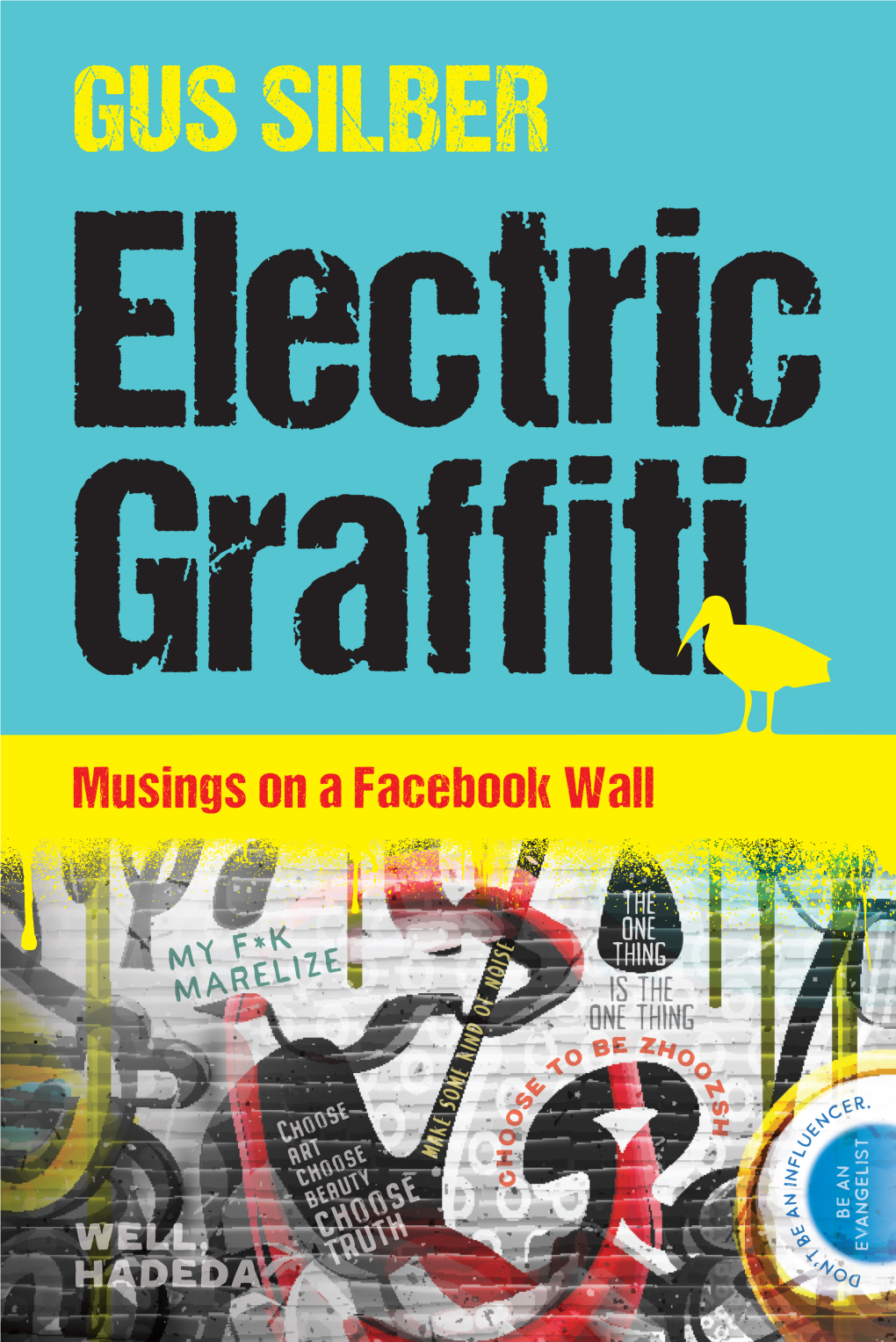

Electric-Graffiti.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How It Works: This Is a Way of Working That

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - How it works: This is a way of working that anyone can do. This will clear your mind. You must not worry. You will not be judged. Relax and enjoy the materials and music. Allow your whole body to loose control and let the materials and music take over. You may use a visual reference if you prefer or let your hand guide you. The materials will do lovely blends by themselves We will start with warm up exercise 1. Then exercise 2 onwards is more of a process that you can do over a few days or in 1 long session. There are 2 processes. I have given you a descriptive plan of making an image using various materials whilst listening to music. Also use a references, E.g still life or landscape, or life drawing. You can have an image in-front of you to respond to. The seascape example you see in picture form in this pack. I listened to the sea and the wind, bird and atmospherics to help with the brush strokes. The still life of a stack of large beach pebbles, where I still listened to music. mainly classical. For this project I have the following music Chinese music that is very simple and you hear each sound and instrument clearly. Talk Talk. From the Album Spirit of Eden. Specifically The Rainbow, Eden, Desire, Inheritance, I believe in you, wealth. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HSfGvuiFOWI Also the Harpist Lavinia Meijer. Her work Gnossienne, Lift off and Metatmorphosis, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FWEymbfwNzo https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=1&v=hV2-zFh3tAU&feature=emb_lo go https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oN99NYFHWEs https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WbCjceRPXyw Your materials are: Bamboo stick, which you can extend by using your own longer stick. -

Kein Weg Zurück in Syrien Warten Gefangene Islamisten Auf Einen Prozess

Strassenmagazin Nr. 472 davon gehen CHF 3.– Bitte kaufen Sie nur bei Verkaufenden 27. März bis 16. April 2020 CHF 6.– an die Verkaufenden mit offiziellem Verkaufspass Corona- Krise Wir brauchen Sie! Daesch Kein Weg zurück In Syrien warten gefangene Islamisten auf einen Prozess. Keiner will ihn führen. Seite 8 Surprise 472/20 3 INFOS ZUM VERKAUFSSTOPP Der Verein Surprise stellt den Verkauf des Strassenmagazins und die Sozialen Stadtrundgänge bis auf Weiteres ein. So soll die besonders vulnerable Gruppe der Armutsbetroffenen geschützt und ein Beitrag zur Eindämmung des Coronavirus geleistet werden. Die Massnahmen gelten bis auf Weiteres. Das aktuelle Surprise Strassenmagazin steht in dieser Zeit kostenlos via Website zum Download bereit und wird in kleiner Auflage weiterhin für AbonnentInnen gedruckt. Der Verein setzt alles daran, die Verkaufenden und Stadtführenden finanziell zu unterstützen und weiterzubegleiten. Wir sind aber dringend auf Ihre Hilfe angewiesen. Die Massnahmen stellen die Verkaufenden und Stadtführenden sowie den Verein Surprise vor massive Herausforderungen. Viele der rund 450 Verkaufenden und 14 Stadtführenden sind armutsbetroffen und für ihr Überleben vom Verkauf des Strassenmagazins und von den Führungen abhängig. Der Verein Surprise wird nicht staatlich subventioniert und ist zu 65 Prozent vom Heftverkauf abhängig. Surprise ist deshalb auf Ihre Solidarität angewiesen. Unterstützen Sie uns mit einer Spende für die betroffenen Verkaufenden und Stadtführenden sowie für den Verein Surprise. Vielen herzlichen Dank für -

Mark Hollis, Leader of ’80S Band Talk Talk, Is Dead

LOG IN Mark Hollis, Leader of ’80s Band Talk Talk, Is Dead Mark Hollis of Talk Talk in 1986. The success of the group’s second album, “It’s My Life,” gave Mr. Hollis and the rest of the band free rein to experiment. Rob Verhorst/Redferns, via Getty Images By Daniel E. Slotnik Feb. 27, 2019 Mark Hollis, the frontman for the British band Talk Talk, which had synth-pop hits in the early 1980s before veering into a more experimental sound that influenced a generation of musicians, has died. Mr. Hollis, about whom personal details are scarce, was widely reported to have been 64. A Facebook page devoted to the group confirmed the death, citing Keith Aspden, Mr. Hollis’s former manager, but provided no further details. Talk Talk was formed in London in 1981, when new wave and synth-pop groups like A Flock of Seagulls and Duran Duran were beginning to receive heavy airplay. Talk Talk’s biggest hits, among them “It’s My Life” and “Such a Shame,” were typical of the style: buoyant songs built on catchy, danceable beats and Mr. Hollis’s plaintive lyrics. The band at first consisted of Mr. Hollis on vocals, guitar and piano, Lee Harris on drums, Paul Webb on bass and Simon Brenner on keyboards. Mr. Brenner left after the group released its first album, “The Party’s Over,” on EMI in 1982, and Tim Friese-Greene became the band’s producer and unofficial fourth member. Talk Talk toured with Duran Duran and broadened its American audience with videos on MTV. -

Classic Pop Magazine

CLASSIC eighties electronic eclectic 58 62 CONTENTS 26 38 95 68 07 74 46 52 Follow us FEATURES SO MUCH TO ANSWER FOR: CLASSIC ALBUM: CELEBRITY SQUARES 88 YOKO ONO 17 SHOCK OF THE NEW 42 Subscribe Subscribe and get Search Classic Pop BOY GEORGE 26 CAMDEN TOWN 52 SPIRIT OF EDEN 68 From Cerys to Edith, the ladies of At 80 years of age, she’s back with a Modern artists inspired by the classics magazine In one of his most candid interviews, Mark Frith explores how its hard- When Talk Talk delivered Spirit Of Eden, BBC 6 Music line up to answer the new album (and great Chinese-food tips!) POSTERS 80 a free CD boxset George O’Dowd tells John Earls about drinking haunts have given rise to some both their label and manager were taken Classic Pop questions of the day Iconic images from pop history (UK readers only) @classicpop DIETER MEIER 19 his new-found happiness and how it of the most popular performers of the aback by its uncompromisingly The vocal half of Yello talks sampling, Page 50 magazine stems from his coming to terms with Eighties and Nineties uncommercial sound. We investigate an NEWS poker and being the ultimate dilettante REVIEWS his creation, Boy George… KIM WILDE 58 album that ultimately finished the band POP-UP 08 The best releases and live concerts… GARY NUMAN 38 One of the most successful female but now stands up to being a classic This month, Howard’s new gear, COMPETITIONS NEW RELEASES 94 …But if you think George opens up to artists of the Eighties reveals a new tour ROXY MUSIC 74 Flock Of Seagulls have theirs nicked, WIN A DAY AT VINTAGE TV 36 Numan, Erasure, Boy George and Prefab Classic Pop, wait until you read this. -

Southbank Centre Announces: a Celebration of Talk Talk and Mark Hollis

Press Release Date: Monday 29 July 2019, 10am Contact: [email protected] / 0207 921 0676 Images: downloadable here Southbank Centre announces: A Celebration of Talk Talk and Mark Hollis Plus: George Dalaras and Kayhan Kalhor Southbank Centre, in partnership with Eat Your Own Ears, today announces a very special night paying tribute to the pioneering and hugely influential 1980s British pop and rock band, Talk Talk, and their late frontman Mark Hollis, at Royal Festival Hall, 26 November 2019. Following the death of the band’s lead singer and chief songwriter in February 2019, A Celebration of Talk Talk and Mark Hollis brings together founding and former members of the band, Simon Brenner, Martin Ditcham, Rupert Black and Jeep Hook, as well as bassist John Mckenzie, to perform as the Spirit of Talk Talk. They will be joined by a line-up of very special guests to be announced, all of whom have been touched by Talk Talk’s music and inspired by Hollis. With Grammy- and Ivor Novello-award winning songwriter Phil Ramacon as musical director, this collection of extraordinary musicians will perform songs from across the band’s eclectic catalogue, including their groundbreaking final records Spirit of Eden (1988) and Laughing Stock (1991) neither of which have ever before been performed live. Bengi Ünsal, Senior Contemporary Music Programmer, Southbank Centre, said: "We are honoured to be holding this beautiful event. Tom and I were talking about staging a celebration of Talk Talk even before Mark passed away. When he sadly died, it became inevitable for us, the fans, and for all the artists who adore the band to pay tribute to them and appreciate the indelible mark they left on music. -

February Newsletter

Systematic Innovation e-zine Issue 180, March 2017 In this month’s issue: Article – Case Study: B2B Intangibles Article – The Morality Of Toast Not So Funny – 2016 Darwin Awards Patent of the Month – Microwave Dehydration Best of The Month – Panarchy Wow In Music – Spirit Of Eden Investments – Isomax Generational Cycles – 4Gs & Generations Biology – Honeyguide Short Thort News The Systematic Innovation e-zine is a monthly, subscription only, publication. Each month will feature articles and features aimed at advancing the state of the art in TRIZ and related problem solving methodologies. Our guarantee to the subscriber is that the material featured in the e-zine will not be published elsewhere for a period of at least 6 months after a new issue is released. Readers’ comments and inputs are always welcome. Send them to [email protected] 2017, DLMann, all rights reserved Case Study: B2B Intangibles Everyone involved in the Business-to-Consumer world is at least beginning to understand the importance of designing for the unspoken intangible outcomes customers are looking for. A lot of times those in the B2B world still don’t get it. We’ll hear sentences like, ‘the contract manager is simply looking to get us to reduce our prices’, or ‘it’s all about legal compliance; so long as we’re compliant, that’s all they want’. We thought a project with a B2C client with a number of adjacent B2B functions might be useful to let the B2B world see what they’re missing out on. The story started a couple of years ago. -

Filmtrax Acquires

PUBLISHIN ., . ... ...-..' ..... -' RADIO 1 RADIO 1 REGIONAL LAST KEY A= Radio 1'A' list ,v/e w/e wh 'wlr wtt wk WEEK'S B= Radio 1'B' list 249 17.9 119 6/ 249 179 CHART C33 Radio 1'C list ACTUAL PLAYS PLAYLGTED PlAYLISTINGS 4Ofmore/ 143 stations' Zombasnaps upChappell's A -HA Touchy! Warner Brothers 13 15 A A 35 37 27 ALMOND, MARC Tears Run Rings Parlophone 16 13 A B 32 28 28 ANTHRAX Make Me Lough Island - 4 --- 4 - ASSOCIATES, THE Head Of Glass WEA 6 7 B B 17 13 62 ASTLEY, RICK She Wants To Dance With Me RCA- 4 - 35 26 16 recorded music librarygems ASWAD Set Them Free Mango 4 4 - 15 11 - BANANARAMA Love, Truth And Honesty London - - 29 26 31 the Chappell Record Music Li- Zomba's West End offices at BEATMASTERS/PP ARNOLD Burn It Up Rhythm King 8 - B --- 45 BLACK Big One A&M 6 6 -- 23 12 Having brary which has now been pur- 11 Greek Street, Soho, which - BOMB THE BASS Don't Make Me Wait Rhythm King 11 12 A A 25 25 14 acquired chased by Zomba Music Pub- already houses Zomba Screen BON 10V1 Bad Medicine Vertigo 8 6 B - 15 - 18 lishing. Music, The Jingle Zone and Chappell's BRAGG, BILLY Great Leap Forward Go! Discs 6 5 ---- 59 is a Zomba comparative Bruton Music. BREATHE Hand To Heaven Siren 10 11 C B 24 34 25 recorded newcomer to the background "We will be embarking upon BROS I Quit CBS 20 15 A A 30 17 6 library field, having first enter- an extensive 12 14 A A 40 38 13 music library, recordingpro- BROTHER BEYOND The Harder 1Try EMI ed this area in 1986 through gramme to broaden and ex- B.V.S,M.P. -

Talk Talk Before the Silence

reDISCOvery presenta: Talk Talk Before the Silence Un’esperienza d’ascolto di Federico Sacchi Regia: Federico Sacchi e Marzia Scarteddu Una coproduzione: Teatro Stabile di Torino – Teatro Nazionale / Docabout Prima Nazionale Teatro Gobetti (TO), 28 Maggio – 02 giugno 2019, www.rediscovery.it Amo il suono ma preferisco il silenzio (Mark Hollis) Il Teatro Stabile di Torino – Teatro Nazionale e l’associazione culturale Docabout presentano la prima nazionale di TALK TALK Before the Silence, la nuova esperienza immersiva di reDISCOvery, la musica come non l’avete mai vista e ascoltata. Quella dei Talk Talk è una delle più imprevedibili e meravigliose metamorfosi musicali nella storia del Pop. Un processo graduale che li ha portati, in un breve lasso di tempo, a passare da una totale aderenza alle mode musicali del momento (i primi anni ’80) a una completa autonomia da queste, creando di fatto un nuovo genere musicale, quello che a posteriori è stato definito “Post Rock”. Un processo inscindibile dall’evoluzione umana e artistica del leader del gruppo Mark Hollis, improbabile Pop Star alla ricerca del “silenzio musicale”. Un artista la cui scomparsa avvenuta il 25 febbraio scorso ha suscitato sincera commozione tra musicisti e appassionati di musica in tutto il mondo. Una notizia che ha avuto grande risonanza in Italia, dove la band ebbe uno straordinario successo tra il 1984 e il 1986. Talk Talk before the Silence è un’esperienza d’ascolto del musicteller Federico Sacchi, con la regia di Federico Sacchi e Marzia Scarteddu, un vero e proprio documentario dal vivo che fonde storytelling, musica, teatro, video e nuove tecnologie. -

Mark Hollis Z Talk Talk Mark Hollis Był Najbardziej Znanym Członkiem Przekaz

Pożegnanie Mark Hollis z Talk Talk Mark Hollis był najbardziej znanym członkiem przekaz. Szukał autorskich brzmień oraz zespołu Talk Talk. Wiadomość o jego śmierci sposobów ekspresji. Dwie ostatnie płyty Talk Talk spotkały się z raczej chłodnym pogrążyła w smutku fanów dźwięków niebanalnych. przyjęciem krytyki. Mówiąc najprościej, uznano, że zespół oszalał. Ale przecież Michał Dziadosz nie wszystko, czego się nie rozumie, musi być zaraz szalone. rodził się 4 stycznia 1955 ro- ku w Londynie. Początkowo chciał zostać psychologiem dziecięcym. W roku 1975 porzucił jed- nak studia i założył swój pierwszy po- ważny zespół – The Reactors. Band na- grał tylko jeden singiel, „I can’t resist” (1977), po czym się rozpadł. Brat Mar- ka, Ed Hollis, który na przełomie lat 70. i 80. XX wieku zajmował się pro- dukcją muzyczną, pomógł znaleźć mu- zyków do nowego składu. Tak powstało Talk Talk. Zespół działał przez okrągłą dekadę (1981-1991). Nagrał zaledwie pięć stu- dyjnych albumów, ale na każdym pre- zentował coraz bardziej ambitną muzy- kę. Początkowo Hollis eksperymentował z new romantic i synth popem (na płycie „The Party’s Over”, 1982), by następnie powędrować w kierunku wysmakowa- Make It”. Poza tym powinna funkcjono- Po rozpadzie grupy w 1991 roku na- nego, akustycznego popu z elementami wać raczej jako całość, a najlepiej sma- stąpiła długa przerwa w działalności rocka i jazzu („It’s My Life”, 1984; „The kuje właśnie w kwietniu. Marka. Dopiero w 1998 wydał swój je- Colour of Spring”, 1986). Skończył na Jeżeli chodzi o przeboje, to zespoło- dyny solowy album bez tytułu. Poza tym odlotowych, intrygujących utworach wi udało się wylansować jeszcze kilka. -

Album Oriented Lists

ALBUM ORIENTED PODCAST LIST EW list NME list Mid Year 100. Ramones, Ramones (1976) D 100. The Smiths, 'Hatful Of Hollow' (1984) E 1980 D 99. Erykah Badu, Mama’s Gun (2000) E 99. The Libertines, 'The Libertines' (2004) D 2002 E 98. Queens of the Stone Age, Songs for the Deaf (2002) D 98. Neutral Milk Hotel, 'In The Aeroplane Over The Sea' (1998) E 2000 D 97. Dusty Springfield, Dusty in Memphis (1969) E 97. The Smiths, 'The Smiths' (1984) D 1976-7 E 96. Dixie Chicks, Home (2002) D 96. Public Enemy, 'Fear Of A Black Planet' (1990) E 1996 D 95. Various Artists, Saturday Night Fever (1977) E 95. Talk Talk, 'Spirit Of Eden' (1988) D 1982-3 E 94. Beyonce, B’Day (2006) D 94. The Rolling Stones, 'Beggars Banquet'(1968) E 1989 D 100. The Who—Live at Leeds (1970) E 93. N.W.A. Straight Outta Compton (1988) D *93. Queens Of The Stone Age 'Songs For The Deaf' (2002) E 1978 E 98. The Zombies—Odyssey and Oracle (1968) E 92. Elliott Smith, Either/Or (1997) E 92. Super Furry Animals, 'Radiator' (1997) D 1997 D 91. Sly and the Family Stone, There’s a Riot Goin’ On (1971) D 91. Prince And The Revolution, 'Purple Rain'(1984) E 1969 E 96. The Byrds—The Notorious Byrd Brothers (1968) E 90. The White Stripes, White Blood Cells (2001) E 90. The Streets 'A Grand Don’t Come For Free' (2004) D 2002-3 D 89. Sleater-Kinney, Dig Me Out (1997) D 89. -

Talk Talk Laughing Stock Mp3, Flac, Wma

Talk Talk Laughing Stock mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Laughing Stock Country: UK & Europe Released: 1991 Style: Alternative Rock, Ethereal MP3 version RAR size: 1727 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1142 mb WMA version RAR size: 1578 mb Rating: 4.5 Votes: 800 Other Formats: AIFF ASF AHX DMF VOX MP3 VOC Tracklist A1 Myrrhman A2 Ascension Day A3 After The Flood B1 Taphead B2 New Grass B3 Runeii Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Polydor Ltd. (UK) Copyright (c) – Polydor Ltd. (UK) Marketed By – Polydor Ltd. (UK) Distributed By – Polydor Ltd. (UK) Recorded At – Wessex Sound Studios Designed At – Peacock Credits Acoustic Bass – Ernest Mothle, Simon Edwards Cello – Paul Kegg, Roger Smith Composed By – Mark Hollis, Tim Friese-Greene Contrabass Clarinet – Dave White Drums – Lee Harris Engineer – Phill Brown Harmonica – Mark Feltham Illustration [Cover Illustration] – James Marsh Management – Keith Aspden Organ, Piano, Harmonium – Tim Friese-Greene Percussion – Martin Ditcham Producer – Tim Friese-Greene Sleeve – Russell Uttley Trumpet, Flugelhorn – Henry Lowther Viola – Garfield Jackson, Gavyn Wright, George Robertson, Jack Glickman, Levine Andrade, Stephen Tees, Wilf Gibson Vocals, Guitar, Piano, Organ – Mark Hollis Notes ℗ 1991 Polydor Ltd UK © 1991 Polydor Ltd UK The copyright in this sound recording is owned by Polydor UK Ltd Also available on LP 847 717-1 - CD 847 717-2 Marketed and distributed in the UK by Polydor Ltd. Recorded at Wessex Studios London Sept 1990 - April 1991 Sleeve at Peacock Design Chrome -

Multimodal Performance Approaches in Electronic Music

Multimodal Performance Approaches in Electronic Music Ben Eyes MA by Research University of York Music January 2015 Abstract Within this portfolio are three pieces which explore the use of video, improvisation and noise in the performance and production of electronic music. The pieces are presented as both fixed media and videos of performances. Also included is preliminary research in the form of two smaller research projects. Video has been used in various forms either as a stimulus to improvisation and composition, as an input for sound control, or more traditionally, as an accompaniment to a composition. The use of improvisation both in the composition and performance of the pieces was also investigated. Noise was used in the composition of the pieces, recorded from field recordings, performed by live instrumentalists or generated by synthesisers. Noise is an important theme in the work and is used to bind sounds together, to create tension and release and to provide a contrast to the more traditional melodic and rhythmic structures. This research endeavors to expand the idea of electronic music performance and explore different approaches to presenting electronic music in a live context. The aim being to break out of the paradigm of the laptop musician staring at a screen and doing little else whilst performing. For each piece I have explored a different mode of performance. For example in the piece Aberfan (2013) the traditional three piece band line up of guitar, percussion and bass, was mutated, creating instruments from springs, heavily distorting conventional instruments such as double bass and using improvising musicians to accompany a film.