Alice's Little Parade

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Uses of Animation 1

The Uses of Animation 1 1 The Uses of Animation ANIMATION Animation is the process of making the illusion of motion and change by means of the rapid display of a sequence of static images that minimally differ from each other. The illusion—as in motion pictures in general—is thought to rely on the phi phenomenon. Animators are artists who specialize in the creation of animation. Animation can be recorded with either analogue media, a flip book, motion picture film, video tape,digital media, including formats with animated GIF, Flash animation and digital video. To display animation, a digital camera, computer, or projector are used along with new technologies that are produced. Animation creation methods include the traditional animation creation method and those involving stop motion animation of two and three-dimensional objects, paper cutouts, puppets and clay figures. Images are displayed in a rapid succession, usually 24, 25, 30, or 60 frames per second. THE MOST COMMON USES OF ANIMATION Cartoons The most common use of animation, and perhaps the origin of it, is cartoons. Cartoons appear all the time on television and the cinema and can be used for entertainment, advertising, 2 Aspects of Animation: Steps to Learn Animated Cartoons presentations and many more applications that are only limited by the imagination of the designer. The most important factor about making cartoons on a computer is reusability and flexibility. The system that will actually do the animation needs to be such that all the actions that are going to be performed can be repeated easily, without much fuss from the side of the animator. -

French Animation History Ebook

FRENCH ANIMATION HISTORY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Richard Neupert | 224 pages | 03 Mar 2014 | John Wiley & Sons Inc | 9781118798768 | English | New York, United States French Animation History PDF Book Messmer directed and animated more than Felix cartoons in the years through This article needs additional citations for verification. The Betty Boop cartoons were stripped of sexual innuendo and her skimpy dresses, and she became more family-friendly. A French-language version was released in Mittens the railway cat blissfully wanders around a model train set. Mat marked it as to-read Sep 05, Just a moment while we sign you in to your Goodreads account. In , Max Fleischer invented the rotoscope patented in to streamline the frame-by-frame copying process - it was a device used to overlay drawings on live-action film. First Animated Feature: The little-known but pioneering, oldest-surviving feature-length animated film that can be verified with puppet, paper cut-out silhouette animation techniques and color tinting was released by German film-maker and avante-garde artist Lotte Reiniger, The Adventures of Prince Achmed aka Die Abenteuer des Prinzen Achmed , Germ. Books 10 Acclaimed French-Canadian Writers. Rating details. Dave and Max Fleischer, in an agreement with Paramount and DC Comics, also produced a series of seventeen expensive Superman cartoons in the early s. Box Office Mojo. The songs in the series ranged from contemporary tunes to old-time favorites. He goes with his fox terrier Milou to the waterfront to look for a story, and finds an old merchant ship named the Karaboudjan. The Fleischers launched a new series from to called Talkartoons that featured their smart-talking, singing dog-like character named Bimbo. -

Chapter 1: Mattes and Compositing Defined Chapter 2: Digital Matting

Chapter 1: Mattes and Compositing Defined Chapter 2: Digital Matting Methods and Tools Chapter 3: Basic Shooting Setups Chapter 4: Basic Compositing Techniques Chapter 5: Simple Setups on a Budget Chapter 6: Green Screens in Live Broadcasts Chapter 7: How the Pros Do It one PART 521076c01.indd 20 1/28/10 8:50:04 PM Exploring the Matting Process Before you can understand how to shoot and composite green screen, you first need to learn why you’re doing it. This may seem obvious: you have a certain effect you’re trying to achieve or a series of shots that can’t be done on location or at the same time. But to achieve good results from your project and save yourself time, money, and frustration, you need to understand what all your options are before you dive into a project. When you have an understanding of how green screen is done on all levels you’ll have the ability to make the right decision for just about any project you hope to take on. 521076c01.indd 1 1/28/10 8:50:06 PM one CHAPTER 521076c01.indd 2 1/28/10 8:50:09 PM Mattes and Compositing Defined Since the beginning of motion pictures, filmmakers have strived to create a world of fantasy by combining live action and visual effects of some kind. Whether it was Walt Disney creating the early Alice Comedies with cartoons inked over film footage in the 1920s or Ray Harryhausen combining stop-motion miniatures with live footage for King Kong in 1933, the quest to bring the worlds of reality and fantasy together continues to evolve. -

Diplomarbeit

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit “Alice’s Journey Through Utopian and Dystopian Wonderlands“ verfasst von Katharina Fohringer, BA angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Mag.phil.) Wien, 2015 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 190 344 333 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Lehramtsstudium Englisch, Deutsch Betreut von: o.Univ.-Prof. Dr. Margarete Rubik TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................ 3 2. ADAPTATION THEORY ................................................................................ 5 2.1. Defining and Categorizing Adaptations .................................................... 5 2.2. Approaches to Analysis ............................................................................ 8 2.2.1. Meaning and Reality .......................................................................... 8 2.2.2. Narrative, Time and Space .............................................................. 11 2.2.3. Film Techniques............................................................................... 14 3. UTOPIA AND DYSTOPIA ON SCREEN...................................................... 16 3.1. Definitions .............................................................................................. 16 3.2. Historical Development of Utopia in Film ............................................... 18 3.3. Categories for Analysis .......................................................................... 21 4. FILM ANALYSIS ......................................................................................... -

Factualwritingfinal.Pdf

Introduction to Disney There is a long history behind Disney and many surprising facts that not many people know. Over the years Disney has evolved as a company and their films evolved with them, there are many reasons for this. So why and how has Disney changed? I have researched into Disney from the beginning to see how the company started and how they got their ideas. This all lead up to what happened in the company including the involvement of pixar, and how the Disney films changed in regards to the content and the reception. Now with the relevant facts you can make up your own mind about when Disney was at their best. Walt Disney Studios was founded in 1923 by brothers Walt Disney and Roy O. Disney. Originally Disney was called ‘Disney Brothers cartoon studio’ that produced a series of short animated films called the Alice Comedies. The first Alice Comedy was a ten minute reel called Alice’s Wonderland. In 1926 the company name was changed to the Walt Disney Studio. Disney then developed a cartoon series with the character Oswald the Lucky Rabbit this was distributed by Winkler Pictures, therefore Disney didn’t make a lot of money. Winkler’s Husband took over the company in 1928 and Disney ended up losing the contract of Oswald. He was unsuccessful in trying to take over Disney so instead started his own animation studio called Snappy Comedies, and hired away four of Disney’s primary animators to do this. Disney planned to get back on track by coming up with the idea of a mouse character which he originally named Mortimer but when Lillian (Disney’s wife) disliked the name, the mouse was renamed Mickey Mouse. -

Identifying the Real Alice: the Replacement of Feminine

Identifying the Real Alice: The Replacement of Feminine Innocence with Masculine Anxiety Amy Horvat This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Research Honors Program in the Department of English Marietta College Marietta, Ohio April 18, 2011 This Research Honors thesis has been approved for the Department of English and the Honors and Investigative Studies Committee by Dr. Carolyn Hares-Stryker April 18, 2011 Faculty thesis advisor Date Dr. Joseph Sullivan April 18, 2011 Thesis committee member Date Dr. Ihor Pidhainy April 18, 2011 Thesis committee member Date Acknowledgements Many thanks to Dr. Carolyn Hares-Stryker for providing guidance, feedback and inspiration, for saying what I meant but did not know how to express, and for understanding about a flexible timeline; Thanks to Dr. Joseph Sullivan for the constant support, both in this project and in everything else, for the reassurance about „growing pains‟ and offering advice about how to fix them, and also for ensuring I was not eaten by sharks and thrown from mountain-sides before completing my project; Thanks to Dr. Ihor Pidhainy for his continued interest and for the epiphany regarding the cantankerous Disney chapter; Thanks also goes to Casey Mercer for proofreading and offering advice about titles, to name the least of it; to Kelly Park for being a willing commiserator; to Diana Horvat for managing the library snafu; and, last but not least, to Chelsea Broderick, James Houck, Amber Vance and Will Vance for listening to one very impassioned late-night lecture on Alice in Cartoonland. Table of Contents Introduction: Constructing Characters and Public Personas …..…………..….…. -

Nationalism, the History of Animation Movies, and World War II Propaganda in the United States of America

University of Akureyri Faculty of Humanities and Social Science Modern Studies 2011 Intersections of Modernity: Nationalism, The History of Animation Movies, and World War II propaganda in the United States of America Kristján Birnir Ívansson Final BA Thesis in the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences University of Akureyri Faculty of Humanities and Social Science Modern studies 2011 Intersections of Modernity: Nationalism, The History of Animation Movies, and World War II propaganda in the United States of America Kristján Birnir Ívansson A final BA Thesis for 180 ECTS unit in the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Instructor: Dr. Giorgio Baruchello Statements I hereby declare that I am the only author of this project and that is the result of own research Ég lýsi hér með yfir að ég einn er höfundur þessa verkefnis og að það er ágóði eigin rannsókna ______________________________ Kristján Birnir Ívansson It is hereby confirmed that this thesis fulfil, according to my judgement, requirements for a BA -degree in the Faculty of Hummanities and Social Science Það staðfestist hér með að lokaverkefni þetta fullnægir að mínum dómi kröfum til BA prófs í Hug- og félagsvísindadeild. __________________________ Giorgio Baruchello Abstract Today, animations are generally considered to be a rather innocuous form of entertainment for children. However, this has not always been the case. For example, during World War II, animations were also produced as instruments for political propaganda as well as educational material for adult audiences. In this thesis, the history of the production of animations in the United States of America will be reviewed, especially as the years of World War II are concerned. -

Disney Channel

Early Enterprises... Walt Disney was born on December 5, 1901 in Chicago Illinois, to his father Elias Disney, and mother Flora Call Disney. Walt had very early interests in art, he would often sell drawings to neighbors to make extra money. He pursued his art career, by studying art and photography by going to McKinley High School in Chicago. Walt began to love, and appreciate nature and wildlife, and family and community, which were a large part of agrarian living. Though his father could be quite stern, and often there was little money, Walt was encouraged by his mother, and older brother, Roy to pursue his talents. Walt joined the Red Cross and was sent overseas to France, where he spent a year driving an ambulance and chauffeuring Red Cross officials. Once he returned from France, he wanted to pursue a career in commercial art, which soon lead to his experiments in animation. He began producing short animated films for local businesses, in Kansas City. By the time Walt had started to create The Alice Comedies, which was about a real girl and her adventures in an animated world, Walt ran out of money, and his company Laugh-O-Grams went bankrupted. Instead of giving up, Walt packed his suitcase and with his unfinished print of The Alice Comedies in hand, headed for Hollywood to start a new business. The early flop of The Alice Comedies inoculated Walt against fear of failure; he had risked it all three or four times in his life. Walt's brother, Roy O. Disney and Walt borrowed an additional $500, and set up shop in their uncle's garage. -

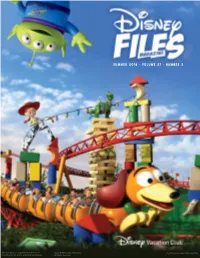

Summer 2018 • Volume 27 • Number 2

Summer 2018 • Volume 27 • Number 2 Slinky® Dog is a registered trademark of Jenga® Pokonobe Associates. Toy Story characters ©Disney/Pixar Poof-Slinky, Inc. and is used with permission. All rights reserved. WeLcOmE HoMe Leaving a Disney Store stock room with a Buzz Lightyear doll in 1995 was like jumping into a shark tank with a wounded seal.* The underestimated success of a computer-animated film from an upstart studio had turned plastic space rangers into the hottest commodities since kids were born in a cabbage patch, and Disney Store Cast Members found themselves on the front line of a conflict between scarce supply and overwhelming demand. One moment, you think you’re about to make a kid’s Christmas dream come true. The next, gift givers become credit card-wielding wildebeest…and you’re the cliffhanging Mufasa. I was one of those battle-scarred, cardigan-clad Cast Members that holiday season, doing my time at a suburban-Atlanta mall where I developed a nervous tick that still flares up when I smell a food court, see an astronaut or hear the voice of Tim Allen. While the supply of Buzz Lightyear toys has changed considerably over these past 20-plus years, the demand for all things Toy Story remains as strong as a procrastinator’s grip on Christmas Eve. Today, with Toy Story now a trilogy and a fourth film in production, Andy’s toys continue to find new homes at Disney Parks around the world, including new Toy Story-themed lands at Disney’s Hollywood Studios (pages 3-4) and Shanghai Disneyland (page 22). -

Life, Scenery and Customs in Sierra Leone and the Gambia, Volume I

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com HISTORY AND BIOGRAPHY. MEMOIRS OF THE HOUSE OE ORLEANS. By W. Cooke Taylor, LL.D. 3 vols., 8vo., 42s. THE COURT AND REIGN OP FRANCIS THE FIRST, KING OF FRANCE, By Miss Pardoe. 2 vols., 8vo., 36s. LIFE OF H.R.H. EDWARD, DUKE OF KENT. By the Rev. Erskine Neale, M.A. 1 vol., 8vo., 14s. DOCTOR JOHNSON: HIS RELIGIOUS LIFE AND HIS DEATH. By the Author of -' Dr. Hookwell. ' 1 vol., post 8vo., 12s. EARTH AND MAN: LECTURES ON COMPARATIVE PHYSICAL GEOGRAPHY. By Arnold Guvot. 1 vol , post 8vo., 5s. THE PHANTOM WORLD; or, the Philosophy of Spirits, Appari tions, &c. By Augustine Calmet. Edited, with an Introduction and Notes, by the Itev. Henry Christmas, M.A., F.R.S. 2 vols., post 8vo., 21s. LIFE AND CORRESPONDENCE OF ADMIRAL SIR WM. SYDNEY SMITH, G. C. B. By John Barrow, Esq., F. R S. 2 vols , 8vo., 28s. THE LETTERS OF PHILIP DORMER STANHOPE, EARL OF CHESTERFIELD. Edited, with Notes, by Lord Mahon. 4 vols., 8vo., 24s. THE HISTORY OF THE FRENCH REVOLUTION. By M. A. Thiers. Translated, with Notes and Illustrations, by F. Shoberl. 5 vols., 8vo„ 25s. THE LIBERTY OF ROME : A History, with an Historical Accou.nt of the Liberty of Ancient Nations. By Samuel Eliot. 2 vols., 8vo , 28s. THE HISTORY OF PETER THE CRUEL, KING OF CASTILE AND LEON. -

Young Boys and Disney: a Qualitative Study of Parents' Perceptions About

Young Boys and Disney: A Qualitative Study of Parents’ Perceptions about their Sons and Disney Media by Caleb Hubbard A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS Major Subject: Communication West Texas A&M University Canyon, Texas August 2017 ABSTRACT This current study analyses parents’ views on the influence and impact Disney has on their sons. Few research studies have focused on the impact Disney has on young males. This study assists in filling that research gap. Using a qualitative approach that included interviews with 11 parents and the theoretical framework provided by Social Learning Theory, my study sought information about parents’ perceptions of how Disney media and Disney merchandise may be influencing their sons. Common themes discovered from coding the interview transcripts were that parents were unaware of the variety of companies owned by Disney, that parents like Disney, that they use Disney media and merchandise as a teaching opportunity, and that they notice an absence of leading male roles in Disney media. Parents identified newer Disney franchises (Marvel, Pixar and Star Wars) as having more influence on their sons, that their sons preferred live action over animation, that their sons’ interest in Disney products was tied to their ages, and that Disney books and Disney produced music was not as interesting to their sons as were action movies. There was a desire expressed by parents for the need to control the somewhat obsessive interest of their sons in particular Disney merchandise and the tendency for their sons to view traditional Disney media as something only girls are interested in. -

The Mystery of a Hansom Cab by Fergus Hume

The Mystery of a Hansom Cab by Fergus Hume PREFACE In its original form, "The Mystery of a Hansom Cab" has reached the sale of 375,000 copies in this country, and some few editions in the United States of America. Notwithstanding this, the present publishers have the best of reasons for believing, that there are thousands of persons whom the book has never reached. The causes of this have doubtless been many, but chief among them was the form of the publication itself. It is for this section of the public chiefly that the present edition is issued. In placing it before my new readers, I have been asked by the publishers thoroughly to revise the work, and, at the same time, to set at rest the many conflicting reports concerning it and myself, which have been current since its initial issue. The first of these requests I have complied with, and the many typographic, and other errors, which disfigured the first edition, have, I think I can safely say, now disappeared. The second request I am about to fulfil; but, in order to do so, I must ask my readers to go back with me to the beginning of all things, so far as this special book is concerned. The writing of the book was due more to accident than to design. I was bent on becoming a dramatist, but, being quite unknown, I found it impossible to induce the managers of the Melbourne Theatres to accept, or even to read a play. At length it occurred to me I might further my purpose by writing a novel.