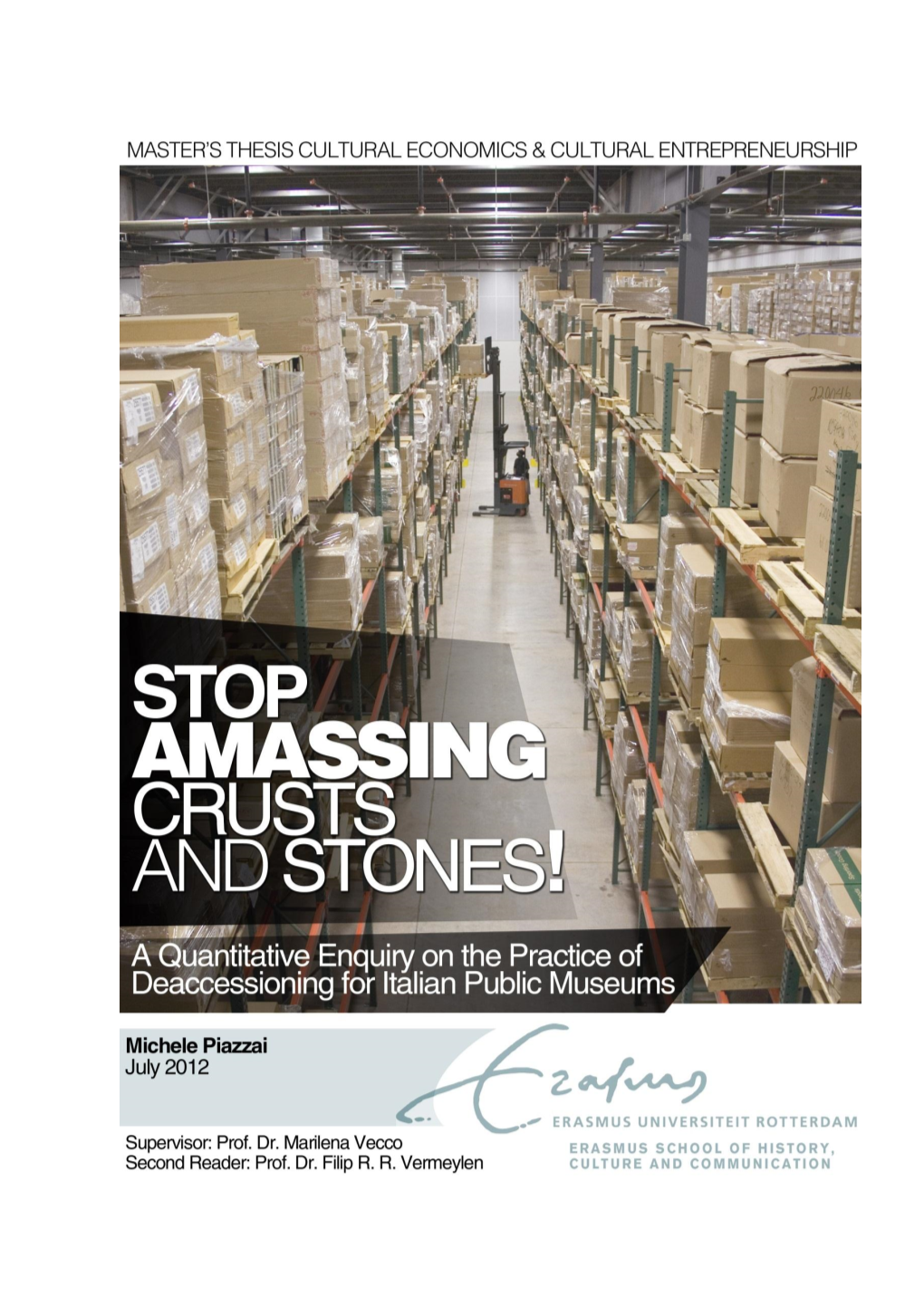

Rethinking Musealization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Redalyc.Giorgio Morandi and the “Return to Order”: from Pittura

Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas ISSN: 0185-1276 [email protected] Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas México AGUIRRE, MARIANA Giorgio Morandi and the “Return to Order”: From Pittura Metafisica to Regionalism, 1917- 1928 Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas, vol. XXXV, núm. 102, 2013, pp. 93-124 Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas Distrito Federal, México Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=36928274005 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative MARIANA AGUIRRE laboratorio sensorial, guadalajara Giorgio Morandi and the “Return to Order”: From Pittura Metafisica to Regionalism, 1917-1928 lthough the art of the Bolognese painter Giorgio Morandi has been showcased in several recent museum exhibitions, impor- tant portions of his trajectory have yet to be analyzed in depth.1 The factA that Morandi’s work has failed to elicit more responses from art historians is the result of the marginalization of modern Italian art from the history of mod- ernism given its reliance on tradition and closeness to Fascism. More impor- tantly, the artist himself favored a formalist interpretation since the late 1930s, which has all but precluded historical approaches to his work except for a few notable exceptions.2 The critic Cesare Brandi, who inaugurated the formalist discourse on Morandi, wrote in 1939 that “nothing is less abstract, less uproot- ed from the world, less indifferent to pain, less deaf to joy than this painting, which apparently retreats to the margins of life and interests itself, withdrawn, in dusty kitchen cupboards.”3 In order to further remove Morandi from the 1. -

Review Essay: Grappling with “Big Painting”: Akela Reason‟S Thomas Eakins and the Uses of History

Review Essay: Grappling with “Big Painting”: Akela Reason‟s Thomas Eakins and the Uses of History Adrienne Baxter Bell Marymount Manhattan College Thomas Eakins made news in the summer of 2010 when The New York Times ran an article on the restoration of his most famous painting, The Gross Clinic (1875), a work that formed the centerpiece of an exhibition aptly named “An Eakins Masterpiece Restored: Seeing „The Gross Clinic‟ Anew,” at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.1 The exhibition reminded viewers of the complexity and sheer gutsiness of Eakins‟s vision. On an oversized canvas, Eakins constructed a complex scene in an operating theater—the dramatic implications of that location fully intact—at Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia. We witness the demanding work of the five-member surgical team of Dr. Samuel Gross, all of whom are deeply engaged in the process of removing dead tissue from the thigh bone of an etherized young man on an operating table. Rising above the hunched figures of his assistants, Dr. Gross pauses momentarily to describe an aspect of his work while his students dutifully observe him from their seats in the surrounding bleachers. Spotlights on Gross‟s bloodied, scalpel-wielding right hand and his unnaturally large head, crowned by a halo of wiry grey hair, clarify his mastery of both the vita activa and vita contemplativa. Gross‟s foil is the woman in black at the left, probably the patient‟s sclerotic mother, who recoils in horror from the operation and flings her left arm, with its talon-like fingers, over her violated gaze. -

The Gross Clinic, the Agnew Clinic, and the Listerian Revolution

Thomas Jefferson University Jefferson Digital Commons Department of Surgery Gibbon Society Historical Profiles Department of Surgery 11-1-2011 The Gross clinic, the Agnew clinic, and the Listerian revolution. Caitlyn M. Johnson, B.S. Thomas Jefferson University Charles J. Yeo, MD Thomas Jefferson University Pinckney J. Maxwell, IV, MD Thomas Jefferson University Follow this and additional works at: https://jdc.jefferson.edu/gibbonsocietyprofiles Part of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, and the Surgery Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Recommended Citation Johnson, B.S., Caitlyn M.; Yeo, MD, Charles J.; and Maxwell, IV, MD, Pinckney J., "The Gross clinic, the Agnew clinic, and the Listerian revolution." (2011). Department of Surgery Gibbon Society Historical Profiles. Paper 33. https://jdc.jefferson.edu/gibbonsocietyprofiles/33 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Jefferson Digital Commons. The Jefferson Digital Commons is a service of Thomas Jefferson University's Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL). The Commons is a showcase for Jefferson books and journals, peer-reviewed scholarly publications, unique historical collections from the University archives, and teaching tools. The Jefferson Digital Commons allows researchers and interested readers anywhere in the world to learn about and keep up to date with Jefferson scholarship. This article has been accepted for inclusion in Department of Surgery Gibbon Society Historical Profiles yb an authorized administrator of the Jefferson Digital Commons. For more information, please contact: [email protected]. Brief Reports Brief Reports should be submitted online to www.editorialmanager.com/ amsurg.(Seedetailsonlineunder‘‘Instructions for Authors’’.) They should be no more than 4 double-spaced pages with no Abstract or sub-headings, with a maximum of four (4) references. -

Architecture on Display: on the History of the Venice Biennale of Architecture

archITECTURE ON DIspLAY: ON THE HISTORY OF THE VENICE BIENNALE OF archITECTURE Aaron Levy and William Menking in conversation with: Vittorio Gregotti Paolo Portoghesi Francesco Dal Co Hans Hollein Massimiliano Fuksas Deyan Sudjic Kurt W Forster Richard Burdett Aaron Betsky Kazuyo Sejima Paolo Baratta archITECTUraL assOCIATION LONDON ArchITECTURE ON DIspLAY Architecture on Display: On the History of the Venice Biennale of Architecture ARCHITECTURAL ASSOCIATION LONDON Contents 7 Preface by Brett Steele 11 Introduction by Aaron Levy Interviews 21 Vittorio Gregotti 35 Paolo Portoghesi 49 Francesco Dal Co 65 Hans Hollein 79 Massimiliano Fuksas 93 Deyan Sudjic 105 Kurt W Forster 127 Richard Burdett 141 Aaron Betsky 165 Kazuyo Sejima 181 Paolo Baratta 203 Afterword by William Menking 5 Preface Brett Steele The Venice Biennale of Architecture is an integral part of contemporary architectural culture. And not only for its arrival, like clockwork, every 730 days (every other August) as the rolling index of curatorial (much more than material, social or spatial) instincts within the world of architecture. The biennale’s importance today lies in its vital dual presence as both register and infrastructure, recording the impulses that guide not only architec- ture but also the increasingly international audienc- es created by (and so often today, nearly subservient to) contemporary architectures of display. As the title of this elegant book suggests, ‘architecture on display’ is indeed the larger cultural condition serving as context for the popular success and 30- year evolution of this remarkable event. To look past its most prosaic features as an architectural gathering measured by crowd size and exhibitor prowess, the biennale has become something much more than merely a regularly scheduled (if at times unpredictably organised) survey of architectural experimentation: it is now the key global embodiment of the curatorial bias of not only contemporary culture but also architectural life, or at least of how we imagine, represent and display that life. -

Monuments to Mundanity at the Socle Du Monde Biennale | Apollo

REVIEWS Monuments to mundanity at the Socle du Monde Biennale Nausikaä El-Mecky 28 APRIL 2017 Socle du Monde (1961), Piero Manzoni. Photo: Ole Bagger. Courtesy of HEART SHARE TWITTER FACEBOOK LINKEDIN EMAIL I am in the middle of nowhere and absolutely terrified. All around me, long strips of white canvas stretch into the distance, suspended above the grass; the wind plays them like strings, making them howl and snap. They are precisely at the level of my neck, and their edges appear razor-sharp. Walking through Keisuke Matsuura’s brilliantly simple Resonance, with its multiple slacklines stretched across two small rises, is like going through a dangerous portal, or navigating a set of laser-beams. Keisuke Matsuura resonance Socle du Monde Biennale 2017 from Keisuke Matsuura on Vimeo. Matsuura’s work is part of the 7th Socle du Monde Biennale in Herning, Denmark. To get there, we drive through an industrial estate in the middle of grey flatlands. Steam billows from a chimney nearby, and a massive hardware store flanks the Biennale’s terrain, which consists of manicured green lawns dotted with several buildings, and intercut by a road or two. Rather than ruining the experience, the encroaching elements of daily life make for a compelling, unpretentious backdrop to the art on display. Matsuura’s work is typical of this Biennale, where things that appear simple, even mundane, suddenly swallow you up in an intense encounter. Even the main building, Denmark’s HEART museum, is a surprise. At first glance it appears to be an unobtrusive, white-walled specimen of Scandi minimalism, but when I happen to look up, I see a beautifully menacing ceiling whose folds and texture resemble parchment or flesh. -

The Agnew Clinic, an 1889 Oil Painting by American Artist Thomas Eakins

Antisepsis and women in surgery 12 The Gross ClinicThe, byPharos Thomas/Winter Eakins, 2019 1875. Photo by Geoffrey Clements/Corbis/VCG via Getty Images The Agnew Clinic, an 1889 oil painting by American artist Thomas Eakins. Universal History Archive/UIG via Getty images Don K. Nakayama, MD, MBA Dr. Nakayama (AΩA, University of California, San Francisco, Los Angeles, 1986, Alumnus), emeritus professor of history 1977) is Professor, Department of Surgery, University of of medicine at Johns Hopkins, referring to Joseph Lister North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, NC. (1827–1912), pioneer in the use of antiseptics in surgery. The interpretation fits so well that each surgeon risks he Gross Clinic (1875) and The Agnew Clinic (1889) being consigned to a period of surgery to which neither by Thomas Eakins (1844–1916) face each other in belongs; Samuel D. Gross (1805–1884), to the dark age of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, in a hall large surgery, patients screaming during operations performed TenoughT to accommodate the immense canvases. The sub- without anesthesia, and suffering slow, agonizing deaths dued lighting in the room emphasizes Eakins’s dramatic use from hospital gangrene, and D. Hayes Agnew (1818–1892), of light. The dark background and black frock coats worn by to the modern era of aseptic surgery. In truth, Gross the doctors in The Gross Clinic emphasize the illuminated was an innovator on the vanguard of surgical practice. head and blood-covered fingers of the surgeon, and a bleed- Agnew, as lead consultant in the care of President James ing gash in pale flesh, barely recognizable as a human thigh. -

CENTRAL PAVILION, GIARDINI DELLA BIENNALE 29.08 — 8.12.2020 La Biennale Di Venezia La Biennale Di Venezia President Presents Roberto Cicutto

LE MUSE INQUIETE WHEN LA BIENNALE DI VENEZIA MEETS HISTORY CENTRAL PAVILION, GIARDINI DELLA BIENNALE 29.08 — 8.12.2020 La Biennale di Venezia La Biennale di Venezia President presents Roberto Cicutto Board The Disquieted Muses. Luigi Brugnaro Vicepresidente When La Biennale di Venezia Meets History Claudia Ferrazzi Luca Zaia Auditors’ Committee Jair Lorenco Presidente Stefania Bortoletti Anna Maria Como in collaboration with Director General Istituto Luce-Cinecittà e Rai Teche Andrea Del Mercato and with AAMOD-Fondazione Archivio Audiovisivo del Movimento Operaio e Democratico Archivio Centrale dello Stato Archivio Ugo Mulas Bianconero Archivio Cameraphoto Epoche Fondazione Modena Arti Visive Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea IVESER Istituto Veneziano per la Storia della Resistenza e della Società Contemporanea LIMA Amsterdam Peggy Guggenheim Collection Tate Modern THE DISQUIETED MUSES… The title of the exhibition The Disquieted Muses. When La Biennale di Venezia Meets History does not just convey the content that visitors to the Central Pavilion in the Giardini della Biennale will encounter, but also a vision. Disquiet serves as a driving force behind research, which requires dialogue to verify its theories and needs history to absorb knowledge. This is what La Biennale does and will continue to do as it seeks to reinforce a methodology that creates even stronger bonds between its own disciplines. There are six Muses at the Biennale: Art, Architecture, Cinema, Theatre, Music and Dance, given a voice through the great events that fill Venice and the world every year. There are the places that serve as venues for all of La Biennale’s activities: the Giardini, the Arsenale, the Palazzo del Cinema and other cinemas on the Lido, the theatres, the city of Venice itself. -

Report 18Th Biennale of Sydney

18TH BIENNALE OF SYDNEY 27 JUNE - 16 SEPT 2012 REPORT Contents A bout the Biennale of Sydney 2 Messages of Support 3 Chairman’s Message 4 CEO’s Report 5 Highlights 7 Art Gallery of New South Wales 12 Museum of Contemporary Art Australia 18 Pier 2/3 24 BENEFACTORS Cockatoo Island 26 Carriageworks 34 Artist Performances and Participatory Projects 36 Opening Week 38 Events and Public Programs 40 2 Biennale Bar @ Pier 2/3 44 Resources 46 Publications and Merchandise 48 Attendance and Audience Research 50 Media and Publicity 52 Marketing Campaign 54 Partners 56 Operations 60 Revenue and Expenditure 61 Artists 62 Official Guests 63 Board and Staff 64 Crew, Interns and Volunteers 65 Supporters and Project Support 66 Cultural Funding 69 Front cover Peter Robinson Gravitas Lite, 2012 Installation view of the 18th Biennale of Sydney (2012) at Cockatoo Island Courtesy the artist; Sutton Gallery, Melbourne; Sue Crockford Gallery, Auckland; and Peter McLeavey Gallery, Wellington This project was made possible with generous assistance from ART50 Trust; Kriselle Baker and Richard Douglas; The Bijou Collection; Jane and Mike Browne; Caffe L’affare; Chartwell Trust; Sarah and Warren Couillault; Sue Crockford Gallery; Kate Darrow; Dean Endowment Trust; Elam School of Fine Arts, The University of Auckland; Alison Ewing; Jo Ferrier and Roger Wall; Dame Jenny Gibbs; Susan and Michael Harte; Keitha and Connel McLaren; Peter McLeavey; Garth O’Brien; Random Art Group; David and Lisa Roberton; Irene Sutton, Sutton Gallery; and Miriam van Wezel and Pete Bossley -

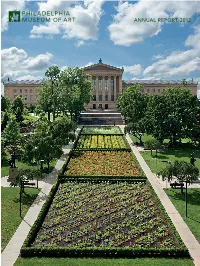

Annual Report 2012

BOARD OF TRUSTEES 4 LETTER FROM THE CHAIR 6 A YEAR AT THE MUSEUM 8 Collecting 10 Exhibiting 20 Teaching and Learning 30 Connecting and Collaborating 38 Building 44 Conserving 50 Supporting 54 Staffing and Volunteering 62 CALENDAR OF EXHIBITIONS AND EVENTS 68 FINANCIAL StATEMENTS 72 COMMIttEES OF THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES 78 SUPPORT GROUPS 80 VOLUNTEERS 83 MUSEUM StAFF 86 A REPORT LIKE THIS IS, IN ESSENCE, A SNAPSHOT. Like a snapshot it captures a moment in time, one that tells a compelling story that is rich in detail and resonates with meaning about the subject it represents. With this analogy in mind, we hope that as you read this account of our operations during fiscal year 2012 you will not only appreciate all that has been accomplished at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, but also see how this work has served to fulfill the mission of this institution through the continued development and care of our collection, the presentation of a broad range of exhibitions and programs, and the strengthening of our relationship to the com- munity through education and outreach. In this regard, continuity is vitally important. In other words, what the Museum was founded to do in 1876 is as essential today as it was then. Fostering the understanding and appreciation of the work of great artists and nurturing the spirit of creativity in all of us are enduring values without which we, individually and collectively, would be greatly diminished. If continuity—the responsibility for sustaining the things that we value most—is impor- tant, then so, too, is a commitment to change. -

American Artists at Venice Biennale

THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART UC.JL ^-V^^JL 1lWB$T33STRKT.HIWYORK1».riY. FOR RELEASE: EUNMY TELEPHONE: CIRCLI 3-8900 April k, I9^k No. 36 PAINTINGS BY DE KOONING AND SHAHN TO BE SHOWN AT 27th VENICE BIENNALE WITH SCULPTURE BY LASSAW, LACHAISE AND SMITH Approximately twenty-seven paintings and drawings by Willem de Kooning and approxi mately thirty-five paintings, drawings and posters by Ben Shahn will be shown in the United States Pavilion at the 27th Venice Biennale International Art exhibition opening in Italy on June 19. A recent sculpture by Ibram Lassaw, a sculpture by Gaston Lachaise and one by Favid Smith will also be exhibited in the Pavilion which was just purchased by the Museum of Modern Art as part of its International Exhibitions Program. The artists were selected by a Museum staff Committee. Andrew Carnduff Ritchie, director of the Museumfs Department of Paint ing and Sculpture, is organizing the retrospective of de Kooning and has chosen the sculpture; James Thrall Soby, Museum trustee and art authority, has selected the works of art by Ben Shahn for the exhibition. The paintings and drawings by Willem de Kooning date from 19^ to the present. He is a recognized leader of the abstract expressionist school, one of the most vital postwar movements in this country, and was represented in the exhibition "Abstract Painting and Sculpture in America" at the Museum of Modern Art in 1951 which was organized by Mr. Ritchie. The retrospective exhibition of works by Ben Shahn, well-known social realist, being assembled by Mr. -

Curriculum Vitae for Koji Enokura

KŌJI ENOKURA Born 1942 in Tokyo, Japan Died 1995 in Tokyo, Japan Education BFA, Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music, Tokyo, Japan, 1966 MFA, Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music, Tokyo, Japan, 1968 One-Person Exhibitions 2018 Tokyo Gallery + BTAP, Tokyo, Japan 2017 Skin, Tokyo Publishing House, Tokyo, Japan Figure, Taka Ishii Gallery, Tokyo, Japan 2016 VeneKlasen/Werner, Berlin, Germany Taka Ishii Gallery, New York, NY 2015 Story & Memory, Tokyo Publishing House, Tokyo, Japan Taka Ishii Gallery, Tokyo, Japan 2013 Blum & Poe, Los Angeles, CA Photographic Works, Gallery Space 23°C, Tokyo, Japan Prints, Ohshima Fine Art, Tokyo, Japan Tokyo Gallery + BTAP, Beijing, China McCaffrey Fine Art, New York, NY 2012 Documentation, Taka Ishii Gallery, Tokyo, Japan Prints, Gallery Space 23°C, Tokyo, Japan Tokyo Gallery + BTAP, Beijing, China 2010 ’90s Print Works and Painting, Shimada Shigeru Gallery, Tokyo, Japan Painting as Sign, Ohshima Fine Art, Tokyo, Japan Photographic Works, Gallery Space 23℃, Tokyo, Japan Ten Ten, Yokota Shigeru Gallery, Tokyo, Japan 2009 ’80s Print Works, Shimada Shigeru Gallery, Tokyo, Japan Drawings, Gallery Space 23°C, Tokyo, Japan & POE LOS ANGELES NEW YORK TOKYO 2008 Paper and Oil, Gallery Space 23°C, Tokyo, Japan 2007 Intervention Ratio, Gallery Space 23°C, Tokyo, Japan 2006 Charcoal Drawings IⅠ, Gallery Space 23°C, Tokyo, Japan SPACE TOTSUKA ’70 – In Photographs, Gallery Space 23°C, Tokyo, Japan 2005 Charcoal Drawings Ⅰ, Gallery Space 23°C, Tokyo, Japan Homage to Kōji Enokura, Nagai Fine Arts, -

1960 Venice Biennale Exhibition Records. Finding Aid Prepared by Clare Kuntz

1960 Venice Biennale Exhibition Records. Finding aid prepared by Clare Kuntz This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit May 17, 2018 Describing Archives: A Content Standard Archives and Manuscripts Collections, The Baltimore Museum of Art 2017 10 Art Museum Drive Baltimore, MD, 21032 (443) 573-1778 [email protected] 1960 Venice Biennale Exhibition Records. Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 3 Biographical Information...............................................................................................................................5 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 6 Administrative Information .........................................................................................................................7 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................ 8 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................8 Collection Inventory.................................................................................................................................... 10 - Page 2 - 1960 Venice Biennale Exhibition Records. Summary Information Repository Archives