Venice Biennale: History and Impact

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Pavilion of Greece at the 58Th International Art Exhibition ― La

Press Release Pavilion of Greece at the 58th International Art Exhibition ― La Biennale di Venezia Artists Panos Charalambous, Eva Stefani, and Zafos Xagoraris represent Greece at the Biennale Arte 2019 in an exhibition titled Mr. Stigl curated by Katerina Tselou May 11–November 24, 2019 Pre-opening: May 8–10, 2019 Inauguration: May 10, 2019, 2 p.m. Giardini, Venice Artists Panos Charalambous, Eva Stefani, and Zafos Xagoraris represent Greece at the 58th International Art Exhibition―La Biennale di Venezia (May11–November 24, 2019) with new works and in situ installations, curated by Katerina Tselou. Lining the Greek Pavilion in Venice―both inside and outside―with installations, images, In the environment they create, there is an constant transposition occurring from grand narratives to personal stories. The unknown (or less known) details of history emerge, subverting Mr. Stigl, who lends his name to the title of the Greek Pavilion exhibition, is a historical paradox, a constructive misunderstanding, a fantastical hero of an unknown story whose poetics take us to a space of doubt, paraphrased sounds, and nonsensical identities and histories. What does history rewrite and what does it conceal? The voices introduced by Panos Charalambous reach us through the rich collection of vinyl records he has accumulated since the 1980s. By combining installations with sonic performances, Charalambous brings forward voices that have been forgotten or silenced, recomposing their orality through an idiosyncratic play of vinyl using eagle’s claws, rose thorns, and agave leaves. His new work An Eagle Was Standing drinking glasses upon which an ecstatic, “ultrasonic” dance is performed—a vortex of deep listening. -

Redalyc.Giorgio Morandi and the “Return to Order”: from Pittura

Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas ISSN: 0185-1276 [email protected] Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas México AGUIRRE, MARIANA Giorgio Morandi and the “Return to Order”: From Pittura Metafisica to Regionalism, 1917- 1928 Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas, vol. XXXV, núm. 102, 2013, pp. 93-124 Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas Distrito Federal, México Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=36928274005 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative MARIANA AGUIRRE laboratorio sensorial, guadalajara Giorgio Morandi and the “Return to Order”: From Pittura Metafisica to Regionalism, 1917-1928 lthough the art of the Bolognese painter Giorgio Morandi has been showcased in several recent museum exhibitions, impor- tant portions of his trajectory have yet to be analyzed in depth.1 The factA that Morandi’s work has failed to elicit more responses from art historians is the result of the marginalization of modern Italian art from the history of mod- ernism given its reliance on tradition and closeness to Fascism. More impor- tantly, the artist himself favored a formalist interpretation since the late 1930s, which has all but precluded historical approaches to his work except for a few notable exceptions.2 The critic Cesare Brandi, who inaugurated the formalist discourse on Morandi, wrote in 1939 that “nothing is less abstract, less uproot- ed from the world, less indifferent to pain, less deaf to joy than this painting, which apparently retreats to the margins of life and interests itself, withdrawn, in dusty kitchen cupboards.”3 In order to further remove Morandi from the 1. -

MOMA Pavilion in Venice

THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART 11 WEST 53 STREET, NEW YORK 19, N. Y FOR RELEASE: MONDAY, TELEPHONE: CIRCLE 5-8900 March 29, 19Si No. 32 MUSEUM OF MODERN ART BUYS EXHIBITION PAVILION IN VENICE William A.M. Burden, President of the Museum of Modern Art, announced today that the Museum has bought the pavilion used for showing modern American art at the Intel-national Art Biennale Exhibitions in Venice, The pavilion, formerly owned by the Grand Central Art Galleries of New York, is the only privately-owned exhibition hall at the famous international art show. The other pavilions are owned by more that 20 governments which officially sponsor exhibitions of contemporary art from their own countries at the Biennale, The Museum of Modern Art has bought the building, Mr* Burden said, in order to insure the continuous representation of art from this country at these famous inter national exhibitions which have been held every two years since 1892 except for the war period* The Venice Biennale is sponsored by the Italian government in order "to bring together some of the most noteworthy and significant examples of con temporary Italian and foreign art" according to the official prospectus, To present as broad a representation of American art as possible the Museum of Modern Art will ask other leading institutions in this country to co-operate in organizing future exhibitions. The exhibition hall in Venice was purchased to implement the Museum's Inter national Exhibitions Program, made possible by a grant to the Museum last year from the Rockefeller Brothers Fund. -

Venice & the Common Ground

COVER Magazine No 02 Venice & the Common Ground Magazine No 02 | Venice & the Common Ground | Page 01 TABLE OF CONTENTS Part 01 of 02 EDITORIAL 04 STATEMENTS 25 - 29 EDITORIAL Re: COMMON GROUND Reflections and reactions on the main exhibition By Pedro Gadanho, Steven Holl, Andres Lepik, Beatrice Galilee a.o. VIDEO INTERVIew 06 REPORT 30 - 31 WHAT IS »COMMON GROUND«? THE GOLDEN LIONS David Chipperfield on his curatorial concept Who won what and why Text: Florian Heilmeyer Text: Jessica Bridger PHOTO ESSAY 07 - 21 INTERVIew 32 - 39 EXCAVATING THE COMMON GROUND STIMULATORS AND MODERATORS Our highlights from the two main exhibitions Jury member Kristin Feireiss about this year’s awards Interview: Florian Heilmeyer ESSAY 22 - 24 REVIEW 40 - 41 ARCHITECTURE OBSERVES ITSELF GUERILLA URBANISM David Chipperfield’s Biennale misses social and From ad-hoc to DIY in the US Pavilion political topics – and voices from outside Europe Text: Jessica Bridger Text: Florian Heilmeyer Magazine No 02 | Venice & the Common Ground | Page 02 TABLE OF CONTENTS Part 02 of 02 ReVIEW 42 REVIEW 51 REDUCE REUSE RECYCLE AND NOW THE ENSEMBLE!!! Germany’s Pavilion dwells in re-uses the existing On Melancholy in the Swiss Pavilion Text: Rob Wilson Text: Rob Wilson ESSAY 43 - 46 ReVIEW 52 - 54 OLD BUILDINGS, New LIFE THE WAY OF ENTHUSIASTS On the theme of re-use and renovation across the An exhibition that’s worth the boat ride biennale Text: Elvia Wilk Text: Rob Wilson ReVIEW 47 ESSAY 55 - 60 CULTURE UNDER CONSTRUCTION DARK SIDE CLUB 2012 Mexico’s church pavilion The Dark Side of Debate Text: Rob Wilson Text: Norman Kietzman ESSAY 48 - 50 NEXT 61 ARCHITECTURE, WITH LOVE MANUELLE GAUTRAND Greece and Spain address economic turmoil Text: Jessica Bridger Magazine No 02 | Venice & the Common Ground | Page 03 EDITORIAL Inside uncube No.2 you’ll find our selections from the 13th Architecture Biennale in Venice. -

Fiona Tan Coming Home

Fiona Tan Sherman Art Foundation Contemporary Coming Home Fiona Tan Coming Home Sherman Contemporary Art Foundation Contents in association with the National Art School 12 Preface Anita Taylor Fiona Tan 14 Introduction Gene Sherman Coming Home 19 Colour Plates A Lapse of Memory 47 Disorient 74 Essay Infinite Crossroads Juliana Engberg 82 Production Credits 84 Artist Biography 88 Artist Bibliography 92 Contributors 94 Acknowledgements 13 It is with enormous pleasure that the National The extension of the project to include the Preface Art School (NAS) joins with Sherman NAS Gallery is a direct outcome of discussions Contemporary Art Foundation (SCAF) to involving the Deans/Directors of the three present ‘Fiona Tan: Coming Home’. The major art schools in Sydney in May 2009, held proposal to extend the project – commissioned at the invitation of Dr Gene Sherman, in which Anita Taylor by SCAF – across our two venues represents a Gene and her team at SCAF proposed an Director significant new partnership for NAS. I believe ongoing dialogue to explore opportunities to National Art School the opportunity afforded by this collaboration engage more extensively with the art students establishes an exciting new direction for both of Sydney. Most importantly, SCAF and NAS our organisations. share a commitment to supporting outstanding The two Sydney venues are each hosting a exhibitions that underscore the value of art and separate body of work: Disorient, 2009, first culture in our society. shown to great acclaim in the Dutch Pavilion at The hard work, commitment and dedication the 53rd Venice Biennale, is screening at SCAF in of a number of individuals are required to Paddington, and A Lapse of Memory, 2007, is deliver an exhibition of this scope. -

Network Venice Brochure

NETWORK 2020 “The Venice Architecture Biennale is the most important architectural show on earth.” Tristram Carfrae Deputy Chair, Arup NETWORK Join us on the journey to 2020 Support Australia in Venice and be a part of something big as we seek to advance architecture through international dialogue, answering the call – How will we live together?. Network, build connections and engage with the local and global architecture and design community and be recognised as a leader with acknowledgement of support throughout Australia’s marketing campaign and on the ground in Venice. Join Network Venice now and maximise your benefits with VIP attendance at the upcoming Creative Director Reveal events being held in Melbourne and Sydney this October. JOURNEY TO National and international and beyond media campaign commences Exhibition development October Creative Director 2019 Shortlist announced 2020 Creative Director Engagement announced at opportunities for a special event Network Venice for partners and supporters supporters VENICE 2020 How will we live together? “We need a new spatial contract. In the context of widening political divides and growing 275k + economic inequalities, we call on architects to Total Exhibition imagine spaces in which we can generously Visitors live together: together as human beings who, despite our increasing individuality, yearn to connect with one another and with other species across digital and real space; together as new households looking for more diverse 95k + and dignified spaces for inhabitation; together Australian -

Portia Zvavahera

Buchanan Building 46 7th Avenue Prinsengracht 371B [email protected] 160 Sir Lowry Road Parktown North 1016 HK Amsterdam www.stevenson.info 7925 Cape Town 2193 Johannesburg The Netherlands +27 21 462 1500 +27 11 403 1055 +31 62 532 1380 @stevenson_za PORTIA ZVAVAHERA. Born 1985 in Harare, Zimbabwe Lives in Harare EDUCATION Diploma in Fine Art, Harare Polytechnic College, Zimbabwe Certificate in Art, BAT Workshop, Harare, Zimbabwe SOLO EXHIBITIONS Stevenson, Cape Town David Zwirner, London, UK , Institute of Contemporary Art Indian Ocean, Port Louis, Mauritius De 11 Lijnen, Oudenburg, Belgium (two-person exhibition) Stevenson, Johannesburg, South Africa Stevenson, Cape Town, South Africa Marc Foxx Gallery, Los Angeles, USA Stevenson, Johannesburg, South Africa Stevenson, Cape Town, South Africa Stevenson, Johannesburg, South Africa Stevenson, Cape Town, South Africa National Gallery of Zimbabwe, Harare SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS Musée d’Art Moderne, Paris, France Pérez Art Museum Miami, USA The Warehouse, Dallas, USA Modern Art, Helmet Row, London, UK , 6th Lubumbashi Biennale, Democratic Republic of Congo Andrew Kreps Gallery, New York, USA 10th Berlin Biennale, Germany Oaxaca, Mexico Zeitz MOCAA, Cape Town, South Africa Garage Museum of Contemporary Art, Moscow, Russia David Lewis Gallery, New York, USA Stevenson, Johannesburg, South Africa Stephen Friedman Gallery, London, UK Stevenson, Cape Town, South Africa Minneapolis Institute of Art, Minnesota, USA Stevenson, Cape Town, South Africa Galerie Hans Mayer, Düsseldorf, Germany Steirischer -

57Th Venice Biennale: the Arsenale | Frieze 12/14/20, 2�48 PM 57Th Venice Biennale: the Arsenale a First Look at ‘Viva Arte Vivaʼ at the Arsenale

57th Venice Biennale: the Arsenale | Frieze 12/14/20, 248 PM 57th Venice Biennale: the Arsenale A first look at ‘Viva Arte Vivaʼ at the Arsenale Over coffee yesterday, a friend suggested writing a poem composed entirely of Venice Biennale exhibition titles. With a little creative punctuation, a stanza made from show names this century would read: ‘Plateau of Humankind, Dreams and Conflicts – The Viewerʼs Dictatorship. The Experience of Art, Think with the Senses, Feel with the Mind: Art in the Present Tense. Making Worlds, Illuminations, The Encyclopaedic Palace, All the Worldʼs Futures. Viva Arte Viva!ʼ It would be an ode to the vague and borderline meaningless. A tribute to one-size- fits-all humanist platitudes. It is a register in which every curator of the Biennaleʼs Arsenale and Central Pavilion exhibition – despite what previous form they may have curating shows of sharp focus and serious scholarship elsewhere – seems compelled to speak. This yearʼs show excels at communicating in this voice; Christine Macelʼs ‘Viva Arte Vivaʼ is a veritable pea-souper of woolly concepts through which I struggled to make headway. https://www.frieze.com/article/57th-venice-biennale-arsenale Page 1 of 10 57th Venice Biennale: the Arsenale | Frieze 12/14/20, 248 PM Rasheed Araeen, Zero to Infinity in Venice, 2016-17, painted wood, dimensions variable, installation view, Arsenale, 57th Venice Biennale. Courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia; photograph: Italo Rondinella Divided into nine ‘chaptersʼ or ‘pavilionsʼ (although as the opening curatorial statement -

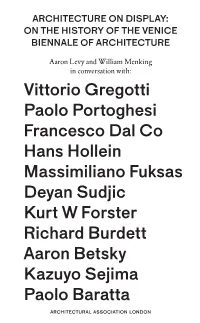

Architecture on Display: on the History of the Venice Biennale of Architecture

archITECTURE ON DIspLAY: ON THE HISTORY OF THE VENICE BIENNALE OF archITECTURE Aaron Levy and William Menking in conversation with: Vittorio Gregotti Paolo Portoghesi Francesco Dal Co Hans Hollein Massimiliano Fuksas Deyan Sudjic Kurt W Forster Richard Burdett Aaron Betsky Kazuyo Sejima Paolo Baratta archITECTUraL assOCIATION LONDON ArchITECTURE ON DIspLAY Architecture on Display: On the History of the Venice Biennale of Architecture ARCHITECTURAL ASSOCIATION LONDON Contents 7 Preface by Brett Steele 11 Introduction by Aaron Levy Interviews 21 Vittorio Gregotti 35 Paolo Portoghesi 49 Francesco Dal Co 65 Hans Hollein 79 Massimiliano Fuksas 93 Deyan Sudjic 105 Kurt W Forster 127 Richard Burdett 141 Aaron Betsky 165 Kazuyo Sejima 181 Paolo Baratta 203 Afterword by William Menking 5 Preface Brett Steele The Venice Biennale of Architecture is an integral part of contemporary architectural culture. And not only for its arrival, like clockwork, every 730 days (every other August) as the rolling index of curatorial (much more than material, social or spatial) instincts within the world of architecture. The biennale’s importance today lies in its vital dual presence as both register and infrastructure, recording the impulses that guide not only architec- ture but also the increasingly international audienc- es created by (and so often today, nearly subservient to) contemporary architectures of display. As the title of this elegant book suggests, ‘architecture on display’ is indeed the larger cultural condition serving as context for the popular success and 30- year evolution of this remarkable event. To look past its most prosaic features as an architectural gathering measured by crowd size and exhibitor prowess, the biennale has become something much more than merely a regularly scheduled (if at times unpredictably organised) survey of architectural experimentation: it is now the key global embodiment of the curatorial bias of not only contemporary culture but also architectural life, or at least of how we imagine, represent and display that life. -

Monuments to Mundanity at the Socle Du Monde Biennale | Apollo

REVIEWS Monuments to mundanity at the Socle du Monde Biennale Nausikaä El-Mecky 28 APRIL 2017 Socle du Monde (1961), Piero Manzoni. Photo: Ole Bagger. Courtesy of HEART SHARE TWITTER FACEBOOK LINKEDIN EMAIL I am in the middle of nowhere and absolutely terrified. All around me, long strips of white canvas stretch into the distance, suspended above the grass; the wind plays them like strings, making them howl and snap. They are precisely at the level of my neck, and their edges appear razor-sharp. Walking through Keisuke Matsuura’s brilliantly simple Resonance, with its multiple slacklines stretched across two small rises, is like going through a dangerous portal, or navigating a set of laser-beams. Keisuke Matsuura resonance Socle du Monde Biennale 2017 from Keisuke Matsuura on Vimeo. Matsuura’s work is part of the 7th Socle du Monde Biennale in Herning, Denmark. To get there, we drive through an industrial estate in the middle of grey flatlands. Steam billows from a chimney nearby, and a massive hardware store flanks the Biennale’s terrain, which consists of manicured green lawns dotted with several buildings, and intercut by a road or two. Rather than ruining the experience, the encroaching elements of daily life make for a compelling, unpretentious backdrop to the art on display. Matsuura’s work is typical of this Biennale, where things that appear simple, even mundane, suddenly swallow you up in an intense encounter. Even the main building, Denmark’s HEART museum, is a surprise. At first glance it appears to be an unobtrusive, white-walled specimen of Scandi minimalism, but when I happen to look up, I see a beautifully menacing ceiling whose folds and texture resemble parchment or flesh. -

CENTRAL PAVILION, GIARDINI DELLA BIENNALE 29.08 — 8.12.2020 La Biennale Di Venezia La Biennale Di Venezia President Presents Roberto Cicutto

LE MUSE INQUIETE WHEN LA BIENNALE DI VENEZIA MEETS HISTORY CENTRAL PAVILION, GIARDINI DELLA BIENNALE 29.08 — 8.12.2020 La Biennale di Venezia La Biennale di Venezia President presents Roberto Cicutto Board The Disquieted Muses. Luigi Brugnaro Vicepresidente When La Biennale di Venezia Meets History Claudia Ferrazzi Luca Zaia Auditors’ Committee Jair Lorenco Presidente Stefania Bortoletti Anna Maria Como in collaboration with Director General Istituto Luce-Cinecittà e Rai Teche Andrea Del Mercato and with AAMOD-Fondazione Archivio Audiovisivo del Movimento Operaio e Democratico Archivio Centrale dello Stato Archivio Ugo Mulas Bianconero Archivio Cameraphoto Epoche Fondazione Modena Arti Visive Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea IVESER Istituto Veneziano per la Storia della Resistenza e della Società Contemporanea LIMA Amsterdam Peggy Guggenheim Collection Tate Modern THE DISQUIETED MUSES… The title of the exhibition The Disquieted Muses. When La Biennale di Venezia Meets History does not just convey the content that visitors to the Central Pavilion in the Giardini della Biennale will encounter, but also a vision. Disquiet serves as a driving force behind research, which requires dialogue to verify its theories and needs history to absorb knowledge. This is what La Biennale does and will continue to do as it seeks to reinforce a methodology that creates even stronger bonds between its own disciplines. There are six Muses at the Biennale: Art, Architecture, Cinema, Theatre, Music and Dance, given a voice through the great events that fill Venice and the world every year. There are the places that serve as venues for all of La Biennale’s activities: the Giardini, the Arsenale, the Palazzo del Cinema and other cinemas on the Lido, the theatres, the city of Venice itself. -

JAVIER TÉLLEZ Born in 1969, in Valencia, Venezuela Lives and Works in Long Island City, Queens, NY

JAVIER TÉLLEZ Born in 1969, in Valencia, Venezuela Lives and works in Long Island City, Queens, NY EDUCATION Arturo Michelena School of Fine Arts, Venezuela SELECTED SOLO EXHBITIONS 2016 To Have Done with the Judgment of God, Koenig & Clinton, New York 2014 Shadow Play, curated by Mirjam Varanidis, Kunsthaus Zürich, Switzerland Games are forbidden in the labyrinth, Walter and McBean Galleries, San Francisco Art Institute, CA Games are forbidden in the labyrinth, REDCAT Gallery, co-produced with Kadist Art Foundation, Los Angeles, CA 2013 Praise of Folly, Stedelijk Museum voor Actuele Kunst, Ghent, Belgium The Conquest of Mexico, Figge von Rosen Galerie, Cologne, Germany 2012 Ungesehen und unerhört II: Javier Téllez, Museum Sammlung Prinzhorn, Heidelberg, Germany Rotations, Galerie Peter Kilchmann, Zürich, Switzerland 2011 Letter on the Blind for the Use of Those Who See, Arthouse at the Jones Center, Austin, TX O Rinoceronte de Dürer, Fruits, Flowers, and Clouds, Museum for Applied Arts, Vienna, Austria Letter on the Blind for the Use of Those Who See, Museum of Contemporary Art Cleveland, OH O Rinoceronte de Dürer, Galerie Arratia Beer, Berlin, Germany 2010 Vasco Araújo/Javier Téllez - Larger than Life, curated by Isabel Carlos, Museo de Arte Contemporánea, Vigo, Spain Vasco Araujo/Javier Téllez - Larger than Life, Museu Calouste Gulbenkian, Lisbon, Portugal 2009 41⁄2, curated by Hilke Wagner, Kunstverein Braunschweig, Germany Mind The Gap, curated by Sabine Schaschl, Kunsthaus Baselland, Switzerland Javier Téllez: International Artist