Some Observations on the Reproductive Behaviour of Rooks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cougar Stalks Deer

predators were aroundi" Science has produced an abundance of evidence that predation on prey, such as rabbits and deer, actually benefits the prey species as a whole by 1) keeping populations at a sustainable level for the amount of vegetative food and other resources in an area, and 2) improving the gene pool over time by preying on the weakest, and therefore ensuring chat the most 6t and survival-strong genes get passed on. Predation makes both predator and prey species stronger. Cougar Stalks Deer Animal Forms, Expanding the Senses, f0Rt R0uTmEs Questioning and Tracking, Listening for Bird Lang,tage tI Sneaking, Imitating Animals, Challenge .!er Mammals 7h Bt}t}K OF IIATURE Southeast: Activate, Southl Focus, Northeastl I{ATURAL CYCTE Open and Listen til0tcATR0s Aliveness and Agrlity, Quiet Mind, ()F AU{ARTilESS Common Sense Prirner Cougars hunt Deer by sneaking up from behind so stealthily that they remain unaware. A Cougar stalks slowly, moving low to the ground, making almost no noise as its hind foot lands exactly where its front foot had been. After a stalking Cougar gets close behind a Deer, they powerfully lunge onto the deer's back, biting into the neck. I bet you didn't know this: Cougars actually have nerve endings on the rips oftheir big canine teeth so that they can feel exactly where to put their teeth and bite, immediately severing the spine and killing the Deer quickly and painlessly. The only protection a Deer has from a stalking Cougar is its sensory awareness. If it hears something and turns to see the Cougar moving, the Deer can bound offeasily to safety and the hunt ends. -

Heraldry Examples Booklet.Cdr

Book Heraldry Examples By Khevron No color on color or metal on metal. Try to keep it simple. Make it easy to paint, applique’ or embroider. Blazon in layers from the deepest layer Per pale vert and sable all semy of caltrops e a talbot passant argent. c up to the surface: i v Field (color or division & colors), e Primary charge (charge or ordinary), Basic Book Heraldry d Secondary charges close to the primary, by Khevron a Tertiary charges on the primary or secondary, Device: An heraldic representation of youself. g Peripheral secondary charges (Chief,Canton,Border), Arms: A device of someone with an Award of Arms. n i Tertiary charges on the peropheral. Badge: An heraldic representation of what you own. z a Name field tinctures chief/dexter first. l Only the first word, the metal Or, B and proper nouns are capitalized. 12 2 Tinctures, Furs & Heraldic 11 Field Treatments Cross Examples By Khevron By Khevron Crosses have unique characteristics and specific names. Tinctures: Metals and Colors Chief Rule #1: No color upon another color, or metal on metal! Canton r r e e t t s i x e n - Fess - i D Or Argent Sable Azure Vert Gules Purpure S Furs Base Cross Latin Cross Cross Crosslet Maltese Potent Latin Cross Floury Counter-Vair Vair Vair in PaleVair-en-pointe Vair Ancient Ermine Celtic Cross Cross Gurgity Crosslet Fitchy Cross Moline Cross of Bottony Jerusalem A saltire vair in saltire Vair Ermines or Counter- Counter Potent Potent-en-pointe ermine Cross Quarterly in Saltire Ankh Patonce Voided Cross Barby Cross of Cerdana Erminois Field -

Heraldic Terms

HERALDIC TERMS The following terms, and their definitions, are used in heraldry. Some terms and practices were used in period real-world heraldry only. Some terms and practices are used in modern real-world heraldry only. Other terms and practices are used in SCA heraldry only. Most are used in both real-world and SCA heraldry. All are presented here as an aid to heraldic research and education. A LA CUISSE, A LA QUISE - at the thigh ABAISED, ABAISSÉ, ABASED - a charge or element depicted lower than its normal position ABATEMENTS - marks of disgrace placed on the shield of an offender of the law. There are extreme few records of such being employed, and then only noted in rolls. (As who would display their device if it had an abatement on it?) ABISME - a minor charge in the center of the shield drawn smaller than usual ABOUTÉ - end to end ABOVE - an ambiguous term which should be avoided in blazon. Generally, two charges one of which is above the other on the field can be blazoned better as "in pale an X and a Y" or "an A and in chief a B". See atop, ensigned. ABYSS - a minor charge in the center of the shield drawn smaller than usual ACCOLLÉ - (1) two shields side-by-side, sometimes united by their bottom tips overlapping or being connected to each other by their sides; (2) an animal with a crown, collar or other item around its neck; (3) keys, weapons or other implements placed saltirewise behind the shield in a heraldic display. -

Heraldry & the Parts of a Coat of Arms

Heraldry reference materials The tomb of Geoffrey V, Count of Anjou (died 1151) is the first recorded example of hereditary armory in Europe. The same shield shown here is found on the tomb effigy of his grandson, William Longespée, 3rd Earl of Salisbury. Heraldry & the Parts of a Coat of Arms From fleur-de-lis.com Here are some charts from Irish surnames.com, but you can look up more specific information for you by searching “charges” and the words that allude to your ancestors’ backgrounds and cultures, if you prefer. Also try: http://www.rarebooks.nd.edu/digital/heraldry/charges/crowns.html for a good reference source on charges. THE COLORS ON COATS OF ARMS Color Meaning Image Generosity Or (Gold) Argent (Silver or White) Sincerity, Peace Justice, Sovereignty, Purpure (Purple) Regal Warrior, Martyr, Military Gules (Red) Strength Azure (Blue) Strength, Loyalty Vert (Green) Hope, loyalty in love Sable (Black) Constancy, Grief Tenne or Tawny (Orange) Worthwhile Ambition Sanguine or Murray Victorious, Patient in Battle (Maroon) LINES ON COATS OF ARMS Name Meaning Image Irish Example Clouds or Air Nebuly Line Wavy Line Sea or Water Gillespie Embattled Fire, Town-Wall Patterson Line Engrailed Earth, Land Feeney Line Invecked Earth, Land Rowe Line Indented Fire Power Line HERALDIC BEASTS Name Meaning Image Irish Example Fierce Courage. In Ireland the Lion represented the 'lion' season, Lawlor Lion prior to the full arrival of Dillon Summer. The symbol can Condon also represent a great Warrior or Chief. Tiger Fierceness and valour Of Regal origin, one of high nature. In Ireland the Fish is associated with the legend of Fionn who became the first to Roche Fish taste the 'salmon of knowledge'. -

Robert Graves the White Goddess

ROBERT GRAVES THE WHITE GODDESS IN DEDICATION All saints revile her, and all sober men Ruled by the God Apollo's golden mean— In scorn of which I sailed to find her In distant regions likeliest to hold her Whom I desired above all things to know, Sister of the mirage and echo. It was a virtue not to stay, To go my headstrong and heroic way Seeking her out at the volcano's head, Among pack ice, or where the track had faded Beyond the cavern of the seven sleepers: Whose broad high brow was white as any leper's, Whose eyes were blue, with rowan-berry lips, With hair curled honey-coloured to white hips. Green sap of Spring in the young wood a-stir Will celebrate the Mountain Mother, And every song-bird shout awhile for her; But I am gifted, even in November Rawest of seasons, with so huge a sense Of her nakedly worn magnificence I forget cruelty and past betrayal, Careless of where the next bright bolt may fall. FOREWORD am grateful to Philip and Sally Graves, Christopher Hawkes, John Knittel, Valentin Iremonger, Max Mallowan, E. M. Parr, Joshua IPodro, Lynette Roberts, Martin Seymour-Smith, John Heath-Stubbs and numerous correspondents, who have supplied me with source- material for this book: and to Kenneth Gay who has helped me to arrange it. Yet since the first edition appeared in 1946, no expert in ancient Irish or Welsh has offered me the least help in refining my argument, or pointed out any of the errors which are bound to have crept into the text, or even acknowledged my letters. -

KEY to the FRESHWATER FISHES of MARYLAND Updated

KEY TO THE FRESHWATER FISHES OF MARYLAND Updated December 2009 KEY TO THE FRESHWATER FISHES OF MARYLAND Compiled by P.F. Kazyak; R.L. Raesly Graphics by D.A. Neely This key to the freshwater fishes of Maryland was prepared for the Maryland Biological Stream Survey to support field and laboratory identifications of fishes known to occur or potentially occurring in Maryland waters. A number of existing taxonomic keys were used to prepare the initial version of this key to provide a more complete set of identifiable features for each species and minimize the possibility of incorrectly identifying new or newly introduced species. Since that time, we have attempted to remove less useful information from the key and have enriched the key by adding illustrations. Users of this key should be aware of the possibility of taking a fish species not listed, especially in areas near the head-of- tide. Glossary of anatomical terms Ammocoete - Larval lamprey. Lateral field - Area of scales between anterior and posterior fields. Basal - Toward the base or body of an object. Mandible - Lower jaw. Branchial groove - Horizontal groove along which the gill openings are aligned in lampreys. Mandibular pores - Series of pores on the ventral surface of mandible. Branchiostegal membranes - Membranes extending below the opercles and connecting at the throat. Maxillary - Upper jaw. Branchiostegal ray - Splint-like bone in the branchiostegal Myomeres - Dorsoventrally oriented muscle bundle on side of fish. membranes. Myoseptum - Juncture between myomeres. Caudal peduncle - Slender part of body between anal and caudal fin. Palatine teeth - Small teeth just posterior or lateral to the medial vomer. -

Peeps at Heraldry Agents America

"gx |[iitrt$ ^tul\xtff SHOP CORKER BOOK |— MfNUE H ,01 FOURTH ».u 1 N. Y. ^M ^.5 ]\^lNicCi\ /^OAHilf'ii ^it»V%.^>l^C^^ 5^, -^M - 2/ (<) So THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA GIFT OF William F. Freehoff, Jr. PEEPS AT HERALDRY AGENTS AMERICA .... THE MACMILLAN COMPANY 64 & 66 FIFTH Avenue, NEW YORK ACSTRAiAETA . OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS 205 FLINDERS Lane, MELBOURNE CANADA ...... THE MACMILLAN COMPANY OF CANADA, LTD. St. MARTIN'S HOUSE, 70 BOND STREET. TORONTO I^TDIA MACMILLAN & COMPANY. LTD. MACMILLAN BUILDING, BOMBAY 309 Bow Bazaar Street, CALCUTTA PLATE 1. HEKALU. SHOWING TABARD ORIGINALLY WORN OVKR MAIL ARMOUR. PEEPS AT HERALDRY BY PHGEBE ALLEN CONTAINING 8 FULL-PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS IN COLOUR AND NUMEROUS LINE DRAWINGS IN THE TEXT GIFT TO MY COUSIN ELIZABETH MAUD ALEXANDER 810 CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE I. AN INTRODUCTORY TALK ABOUT HERALDRY - I II. THE SHIELD ITS FORM, POINTS, AND TINCTURES - 8 III. DIVISIONS OF THE SHIELD - - - - l6 IV. THE BLAZONING OF ARMORIAL BEARINGS - -24 V. COMMON OR MISCELLANEOUS CHARGES - " 3^ VI. ANIMAL CHARGES - - - - "39 VII. ANIMAL CHARGES (CONTINUED) - - "47 VIII. ANIMAL CHARGES (CONTINUED) - - " 5^ IX. INANIMATE OBJECTS AS CHARGES - - - ^3 X. QUARTERING AND MARSHALLING - - "70 XI. FIVE COATS OF ARMS - - - "74 XII. PENNONS, BANNERS, AND STANDARDS - - 80 VI LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS PLATE 1. Herald showing Tabard, originally Worn over Mail Armour - - - - - frontispiece FACING PAGE 2. The Duke of Leinster - - - - 8 Arms : Arg. saltire gu. Crest : Monkey statant ppr., environed round the loins and chained or. Supporters : Two monkeys environed and chained or. Motto : Crom a boo. - - 3. Marquis of Hertford - - - 16 Arms : Quarterly, ist and 4th, or on a pile gu., between 6 fleurs-de- lys az,, 3 lions passant guardant in pale or ; 2nd and 3rd gu., 2 wings conjoined in lure or. -

Heraldry As Art : an Account of Its Development and Practice, Chiefly In

H ctwWb gc M. L. 929.6 Ev2h 1600718 f% REYNOLDS HISTORICAL GENEALOGY COLLECTION ALLEN COUNTY PUBLIC LIBRARY 3 1833 00663 0880 HERALDRY AS ART HERALDRY AS ART AN ACCOVNT OF ITS DEVELOPMENT AND PRACTICE CHIEFLY IN ENGLAND BY G W. EVE BTBATSFORD, 94 HIGH HOLBORN LONDON I907 Bctlkr & Tanner, The Selwood Printing ^Vobks, Frome, and London. 1GC0718 P r e fa c e THE intention of this book is to assist the workers in the many arts that are concerned with heraldry, in varying degrees, by putting before them as simply as possible the essential principles of heraldic art. In this way it is hoped to contribute to the improve- ment in the treatment of heraldry that is already evident, as a result of the renewed recognition of its ornamental and historic importance, but which still leaves so much to be desired. It is hoped that not only artists but also those who are, or may become, interested in this attractive subject in other ways, will find herein some helpful information and direction. So that the work of the artist and the judgment and appreciation of the public may alike be furthered by a knowledge of the factors that go to make up heraldic design and of the technique of various methods of carrying it into execution. To this end the illustrations have been selected from a wide range of subjects and concise descriptions of the various processes have been included. And although the scope of the book cannot include all the methods of applying heraldry, in Bookbinding, Pottery and Tiles for example, the principles that are set forth will serve ;; VI PREFACE all designers who properly consider the capabilities and limitations of their materials. -

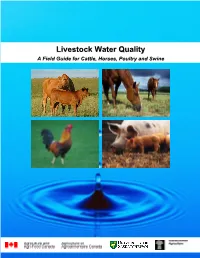

Livestock Water Quality a Field Guide for Cattle, Horses, Poultry, and Swine

LLiivveessttoocckk WWaatteerr QQuuaalliittyy A Field Guide for Cattle, Horses, Poultry and Swine Livestock Water Quality A Field Guide for Cattle, Horses, Poultry, and Swine Andrew A. Olkowski, PhD., DVM., MSc., BSc., (Biochemistry) University of Saskatchewan Disclaimer This publication and the information, opinions, and recommendations contained in it are presented as a free general public service, and not intended to serve any particular reader’s needs. Readers are advised that the Minister and Department of Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) make no assurance or warranty of any kind, either express or implied, as to the publication or its content, including, without limitation, any assurance or warranty concerning the accuracy, completeness, reliability, or suitability or fitness for purpose of the information, opinions and recommendations contained in it. Responsibility for any and all risks associated with the interpretation and any use or application of the contents of this publication rests solely with the reader. Readers using or applying the information, opinions, and recommendations contained in it do so upon the express understanding and agreement that AAFC and its Minister, officers, servants, employees, and agents shall not be liable for any damages or losses whatsoever, whether direct or indirect, consequential, incidental, special or general, economic or otherwise, that may arise out of the reader’s interpretation, use, or application of the information, opinions, and recommendations contained in it. While AAFC endeavours to provide useful and reasonably accurate information, opinions, and recommendations, readers accept that this disclaimer means that NO LIABILITY shall attach for the use or application of the information, opinions, and recommendations contained in this publication. -

British Heraldry (1921)

BERKELEY / LIBRARY ^ UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA J BRITISH HERALDRY BRITISH HERALDRY I, Arms of James I. 2, Great Seal of Scotland BRITISH HERALDRY CYRIL DAVENPORT V.D.. J.P., F.S.A. WITH 210 ILLUSTRATIONS BY TH^ AUTHOR NEW YORK E. P. DUTTON AND COMPANY PUBLISHERS Digitized by the Internet Arciiive in 2007 witii funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation littp://www.archive.org/details/britislilieraldryOOdavericli — CKicii CONTENTS CHAPTER I PAGE The Beginnings of Armory—The Bayeux Tapestry—Early Heraldic Manuscripts—The Heralds* College—Tourna- ments I CHAPTER n Shields and their Divisions— Colours a; d their Linear Repre- sentations as Designed by Silvestro Petra Sancta—Furs Charges on Shields— Heraldic Terms as to position and Arrangement of Charges—Marshalling—Cadency—How to Draw Up Genealogical Trees 13 CHAPTER HI Badges and Crests— List of Crests of Peers and Baronets, 191 2- 1920 53 CHAPTER IV Supporters—List of Supporters of Peers and Baronets, 1912- 1920 .143 CHAPTER V The Royal Heraldry of Great Britain and Ireland . 200 Index 217 166 — —— LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS rms of James I. Great Seal of Scotland . Frontispiece PAGE late I. Ancient Heraldry 2 I. English Shield from the Bayeux Tapestry—2. North American Tent with Armorial Totem—3. Rhodian Warrior with Armorial Shield 4. Standardof Duke William of Normandy— 5. Greek figure of Athene with Armorial Shield— 6. Norse Chessman with Armorial Shield 7. Standard of King Harold— 8. Norman Shield from the Bayeux Tapestry—9. Dragon Standard of Wessex. ate II. Divisions of Shields of Arms, etc 14 I. Paly—2. Bendy Sinister—3. Lozengy—4, Barry—5. -

Line-Of-Sight Pursuit in Monotone and Scallop Polygons

Line-of-Sight Pursuit in Monotone and Scallop Polygons Lindsay Berry∗ Andrew Beveridge† Jane Butterfield‡ Volkan Isler§ Zachary Keller¶ Alana Shinek Junyi Wang† Abstract We study a turn-based game in a simply connected polygonal environment Q between a pursuer and an adversarial evader . Both players can move in a straight line to any point withinP unit distance during theirE turn. The pursuer wins by capturing the evader, meaning that their distance satisfies d( , ) 1, while theP evader wins by eluding capture forever. Both players have a map ofP theE environment,≤ but they have different sensing capabilities. The evader always knows the location of . Meanwhile, only has line-of-sight visibility: observesE the evader’s position onlyP when the line segmentP connecting them lies entirelyP within the polygon. Therefore must search for when the evader is hidden from view. P E We provide a winning strategy for in two families of polygons: monotone polygons and scallop polygons. In both families,P a straight line L can be moved continuously over Q so that (1) L Q is a line segment and (2) every point on the boundary ∂Q is swept exactly once. These∩ are both subfamilies of strictly sweepable polygons. The sweeping motion for a monotone polygon is a single translation, and the sweeping motion for a scallop polygon is a single rotation. Our algorithms use rook’s strategy during its pursuit phase, rather than the well-known lion’s strategy. The rook’s strategy is crucial for obtaining a capture time that is linear in the area of Q. -

Rook's Restaurant American Bistro

Rook’s Restaurant American Bistro ^ ] BBQ Red Skins 9 Pulled Pork, Cheddar Cheese with Chipotle Sour Cream and Green Onions Grilled Shrimp Cocktail 11 A Served South of the Border Style in a Spicy Tomato Broth P Calamari and Rock Shrimp 11 Crispy Fried, Hot Sweet Peppers and Lemon Aioli P E Crispy String Beans 9 Tempura Battered with Soy Chili Dipping Sauce T I Seared Crab Cakes 11 with Real Remoulade Z Hummus 8 E Warm Flat Bread and Vegetables R Grilled Chicken Quesadilla 9 S Jack Cheese, Pico De Gallo, Guacamole, Sour Cream and Salsa House Potato Chips and Dip 8 Lemon, Pepper and Parmesan Seasoning 11 Tasty Wings 10 Tossed in Hot Sauce with Rook’s Blue Cheese Dressing Angus Sliders 9 Three Demi Burgers Topped with Cheddar, Pickle and Fried Onions Mini Crunchy Tacos 9 Chicken with Chipotle Sour Cream, Cilantro and Queso Fresco Consuming raw or under cooked meats, poultry, seafood, shellfish, or eggs may increase your risk for food-bourne illness. S O Seafood Gumbo 7 U Corn & Crab Chowder 7 P S Classic Caesar Half 6 Full 9 Rook’s Caesar Dressing, Garlicky Croutons and Imported Parmesan Add Grilled Chicken 3 Garden House 9 S Mixed Greens, Shredded Cheddar, Bacon, Tomato, Egg and Croutons A Add Grilled Chicken 3 L A Thai Chicken Salad 13 D Tossed Asian Salad Mix in a Soy Vinaigrette Dressing, Crispy Noodles, S Peanuts, Cucumbers, Scallion and Carrots. Arugula Salad 9 Toasted Almonds, Cranberries, Mandarin Oranges, Red Onions and Roasted Red Bell Peppers with a White Balsamic Vinaigrette Iceberg Salad 12 Chilled Iceberg, Crispy Bacon, Tomato,