Revival of 'Crooked'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lotus Infuses Downtown Bloomington with Global

FOR MORE INFORMATION: [email protected] || 812-336-6599 || lotusfest.org FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: 8/26/2016 LOTUS INFUSES DOWNTOWN BLOOMINGTON WITH GLOBAL MUSIC Over 30 international artists come together in Bloomington, Indiana, for the 23rd annual Lotus World Music & Arts Festival. – COMPLETE EVENT DETAILS – Bloomington, Indiana: The Lotus World Music & Arts Festival returns to Bloomington, Indiana, September 15-18. Over 30 international artists from six continents and 20 countries take the stage in eight downtown venues including boisterous, pavement-quaking, outdoor dance tents, contemplative church venues, and historic theaters. Representing countries from A (Argentina) to Z (Zimbabwe), when Lotus performers come together for the four-day festival, Bloomington’s streets fill with palpable energy and an eclectic blend of global sound and spectacle. Through music, dance, art, and food, Lotus embraces and celebrates cultural diversity. The 2016 Lotus World Music & Arts Festival lineup includes artists from as far away as Finland, Sudan, Ghana, Lithuania, Mongolia, Ireland, Columbia, Sweden, India, and Israel….to as nearby as Virginia, Vermont, and Indiana. Music genres vary from traditional and folk, to electronic dance music, hip- hop-inflected swing, reggae, tamburitza, African retro-pop, and several uniquely branded fusions. Though US music fans may not yet recognize many names from the Lotus lineup, Lotus is known for helping to debut world artists into the US scene. Many 2016 Lotus artists have recently been recognized in both -

Little Rock, Arkansas

Society for American Music Thirty-Ninth Annual Conference Hosted by University of Arkansas at Little Rock Peabody Hotel 6–10 March 2013 Little Rock, Arkansas Mission of the Society for American Music he mission of the Society for American Music Tis to stimulate the appreciation, performance, creation, and study of American musics of all eras and in all their diversity, including the full range of activities and institutions associated with these musics throughout the world. ounded and first named in honor of Oscar Sonneck (1873–1928), the early Chief of the Library of Congress Music Division and the Fpioneer scholar of American music, the Society for American Music is a constituent member of the American Council of Learned Societies. It is designated as a tax-exempt organization, 501(c)(3), by the Internal Revenue Service. Conferences held each year in the early spring give members the opportunity to share information and ideas, to hear performances, and to enjoy the company of others with similar interests. The Society publishes three periodicals. The Journal of the Society for American Music, a quarterly journal, is published for the Society by Cambridge University Press. Contents are chosen through review by a distinguished editorial advisory board representing the many subjects and professions within the field of American music.The Society for American Music Bulletin is published three times yearly and provides a timely and informal means by which members communicate with each other. The annual Directory provides a list of members, their postal and email addresses, and telephone and fax numbers. Each member lists current topics or projects that are then indexed, providing a useful means of contact for those with shared interests. -

Les Pages Sur Les Festivals D'été

festivalsSummer d’été Une pléiade de festivals de musique classique se disputent chaque été les faveurs des mélomanes. Le plaisir des yeux y rejoint celui des oreilles, les sites étant souvent splendides et totalement dépaysants. La Scena en brosse, ce mois-ci, un portrait pastoral. A growing number of festivals appeal to classical music lovers. They aim to please their patrons’ ears, but also they strive to delight their eyes, being located in bucolic pastures. This month, La Scena attempts to capture their unique appeal. 3 2pm. StAC. Ensemble vocal Joseph-François- über die Folie d’Espagne, Wq. 118/9, H.263 JULY Perrault; Oakville Children’s Choir; Academic (1778); Mozart: Fantaisie in C minor, K.V. 475 12 20h. EcLER. $10-22. Chausson: Quatuor; Brahms: Choir of Adam Mickiewicz University; Bach (1785); 9 Variationen über ein Menuett von Quatuor #3 en sol mineur. Quatuor Kandinsky Children’s Chorus of Scarborough; Prince of Duport, K.V. 573 (1789); Haydn: Variations in F 13 20h. ÉNDVis. $10-22. Piazzolla: “Four for Tango”; Wales Collegiate Chamber Choir; Choral Altivoz minor, Hob. xvii/6 (1793); Beethoven: 6 Castonguay-Prévost-Michaud: “Redemptio” 3 8pm. A&CC. Cantare-Cantilena Ensemble; Young Variations, op.34 (1802). Cynthia Millman-Floyd, (poème Serge-Patrice Thibodeau); Dvorak: Voices of Melbourne; Daughter of the Baltic fortepiano “Cypresses” #6 10 5 12; Chostakovich: 2 Pieces 3 8pm. GowC. St. John’s Choir; Scunthorpe Co- 3 8pm. DAC Sir James Dunn Theatre. $20-25. Guy: for String Quartet; Reinberger: Nonet op.139. Operative Junior Choir; Amabile Boys Choir Nasca Lines. Upstream Orchestra; Barry Guy, bass Quatuor Arthur-LeBlanc; Eric Lagacé, contre- 4 8pm. -

Bio / Press Quotes

BIO Over the past 18 years the trad Quebec group Genticorum has become a fxture on the international world, trad, folk and Celtic music circuit! "he band#s six albums met with critical acclaim in Canada, the $nited %tates and &urope, assuring the band a brilliant future. 'nown for its energy and its stage presence, Genticorum has given more than 800 concerts in more than 15 countries. *irmly rooted in the soil of their native land, the energetic and original traditional +power trio# also incorporates the dynamism of today#s North -merican and &uropean folk cultures in their music! "hey weave precise and intricate fddle, .ute and accordion work, gorgeous vocal harmonies, energetic foot percussion and guitar accompaniment into a big and /ubilant musical feast! "heir distinctive sound, sense of humour and stage presence makes them a supreme crowd pleaser! DISCOGRAPHY 0003 2e Galarneau 0005 3alins 4laisirs 0008 2a 5ibournoise 0011 Nagez 7ameurs 0013 &nregistré 2ive 0018 -vant l9orage PRESS QUOTES :Genticorum have a rightful place amongst the new generation of internationally recogni6ed Quebequois 5ands. 5eautifully presented recording<!! harmonising brilliantly!= THE LIVING TRADITION :*or a three piece, Genticorum makes a very full and glorious noise, both instrumentally and vocally< "his is a band that#s going to go places!> SING OUT MAGAZINE :"he record exhibits incredible depth and /oie de vivre, a hallmark of the group since their frst release ?!!!@ it#s all wonderful stuff and Nagez 7ameurs demonstrates, yet again, why Genticorum are -

Embracing Change: National Arts Centre 2019-2020 Annual Report

Zéro Mani Soleymanlou Role Photo © Xavier Inchauspé The National Arts Centre (NAC) is Canada’s bilingual, multi-disciplinary home for the performing arts. The NAC presents, creates, produces and co-produces performing arts programming in various streams — the NAC Orchestra, Dance, English Theatre, French Theatre, Indigenous Theatre, and Popular Music and Variety — and nurtures the next generation of audiences and artists from across Canada. The NAC is located in the National Capital Region on the unceded territory of the Algonquin Anishinaabe Nation Mandate The NAC is governed by the National Arts Centre Act, which defines its mandate as follows: to operate and maintain the Centre; to develop the performing arts in the National Capital Region; and to assist the Canada Council for the Arts in the development of the performing arts elsewhere in Canada. Accountability and Funding As a Crown Corporation, the NAC reports to Parliament through the Minister of Canadian Heritage. Of the NAC’s total revenue, less than half is derived from an annual Parliamentary appropriation, while more than half comes from earned revenue — box office sales, food and beverage services, parking services and hall rentals – and from the NAC Foundation. Each year, the Minister of Canadian Heritage tables the NAC annual report in Parliament. The Auditor General of Canada is the NAC’s external auditor. Embracing Structure A Board of Trustees consisting of 10 members from across Canada, chaired by Adrian Burns, Change oversees the NAC. The President and CEO is Christopher Deacon. The creative leadership team is composed of Heather Gibson (Popular Music and Variety), Brigitte Haentjens (French Theatre), Jillian Keiley (English Theatre), Kenton Leier (Executive Chef), Cathy Levy (Dance), Kevin Loring (Indigenous Theatre), Heather Moore (National Creation Fund) and Alexander Shelley (NAC Orchestra). -

PS1.12 Melodic Similarity in Traditional French-Canadian

MELODIC SIMILARITY IN TRADITIONAL FRENCH-CANADIAN INSTRUMENTAL DANCE TUNES Laura Risk Lillio Mok Andrew Hankinson Julie Cumming Schulich School of Music Centre for Interdisciplinary Research in Music Media and Technology (CIRMMT) McGill University [email protected] (versions of the same tune) previously unrecognized as ABSTRACT being musically related. Commercial recordings of French-Canadian instrumental Broadly speaking, the traditional instrumental music dance tunes represent a varied and complex corpus of of Québec is similar to the instrumental traditions of study. This was a primarily aural tradition, transmitted Ireland, Scotland and the United States. The repertoire from performer to performer with few notated sources consists primarily of short, fast-paced dance tunes until the late 20th century. Practitioners routinely usually performed on the violin, accordion, or combined tune segments to create new tunes and harmonica. With very few exceptions, each tune has at personalized settings of existing tunes. This has resulted least two strains (sections), commonly labeled “A” and in a corpus that exhibits an extreme amount of variation, “B.” Many of the tunes have their roots in British Isles even among tunes with the same name. In addition, the and American fiddling traditions, though others are same tune or tune segment may appear under several derived from popular French songs or early twentieth- different names. century marching-band repertoire [8; 13; 23]. Previous attempts at building systems for automated retrieval and ranking of instrumental dance tunes 2. THE CHALLENGE perform well for near-exact matching of tunes, but do The French-Canadian tradition has developed almost not work as well in retrieving and ranking, in order of exclusively as an aural and recorded tradition. -

Spring 2020 Thursdays | 4:30–6:00Pm |

Music Department Colloquium Series Spring 2020 Thursdays | 4:30–6:00pm | This lecture series showcases new work by performers, composers, and scholars in ethnomusicology, musicology, music theory, sound art, and cultural history. The colloquia also invite dialogue with professionals working in arts education and in librarianship. The series is organized by Jane Alden. All colloquium held in Adzenyah Rehearsal Hall 003 unless otherwise posted. Spring 2020 Lynsey Callaghan - Conductor/Educator/Scholar, Dublin “Revisiting the Kodály Concept in Irish Choral Music Education January 30, 2020 4:30 p.m. This presentation draws on personal experience to explore Zoltán Kodály’s music pedagogy and the philosophy associated with this Hungarian music educator. Following a brief overview of the music- educational reforms that were achieved by Kodály and his collaborators and students, I will outline briefly the political and cultural context in which Kodály achieved these reforms. Moving the focus to present- day Ireland, I use a range of reports and publications to summarize current music education policy and practice, and I assess Kodály’s philosophy of music education in relation to the contemporary Irish context. Finally, I present Dublin Youth Choir as a case study of an organization that had adopted and adapted Kodály’s philosophy of music education to meet the needs of contemporary Irish society. Lynsey Callaghan is an Irish conductor and educator with research interests in Kodály training and medieval musicology. She has conducted the RTÉ National Symphony Orchestra, the RTÉ Concert Orchestra, and the Ulster Orchestra. Passionate about providing opportunities for youth choral music, in 2017, Lynsey founded Dublin Youth Choir, which now comprises Chamber Choir, Youth Choir, Male Voice Choir, and Junior Choir, and is still growing! Lynsey is also the Musical Director of the Belfast Philharmonic Youth and Chamber Choirs. -

TMS 3-1 Pages Couleurs

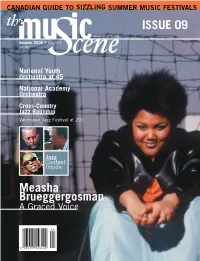

TMS3-4cover.5 2005-06-07 11:10 Page 1 CANADIAN GUIDE TO SIZZLING SUMMER MUSIC FESTIVALS ISSUE 09 www.scena.org Summer 2005 • Vol. 3.4 $4.95 National Youth Orchestra at 45 National Academy Orchestra Cross-Country Jazz Roundup Vancouver Jazz Festival at 20! Jazz Contest Inside Measha Brueggergosman A Graced Voice 0 4 0 0 6 5 3 8 5 0 4 6 4 4 9 TMS3-4 glossy 2005-06-06 09:14 Page 2 QUEEN ELISABETH COMPETITION 5 00 2 N I L O I V S. KHACHATRYAN with G. VARGA and the Belgian National Orchestra © Bruno Vessié 1st Prize Sergey KHACHATRYAN 2nd Prize Yossif IVANOV 3rd Prize Sophia JAFFÉ 4th Prize Saeka MATSUYAMA 5th Prize Mikhail OVRUTSKY 6th Prize Hyuk Joo KWUN Non-ranked laureates Alena BAEVA Andreas JANKE Keisuke OKAZAKI Antal SZALAI Kyoko YONEMOTO Dan ZHU Grand Prize of the Queen Elisabeth International Competition for Composers 2004: Javier TORRES MALDONADO Finalists Composition 2004: Kee-Yong CHONG, Paolo MARCHETTINI, Alexander MUNO & Myung-hoon PAK Laureate of the Queen Elisabeth Competition for Belgian Composers 2004: Hans SLUIJS WWW.QEIMC.BE QUEEN ELISABETH INTERNATIONAL MUSIC COMPETITION OF BELGIUM INFO: RUE AUX LAINES 20, B-1000 BRUSSELS (BELGIUM) TEL : +32 2 213 40 50 - FAX : +32 2 514 32 97 - [email protected] SRI_MusicScene 2005-06-06 10:20 Page 3 NEW RELEASES from the WORLD’S BEST LABELS Mahler Symphony No.9, Bach Cantatas for the feast San Francisco Symphony of St. John the Baptist Mendelssohn String Quartets, Orchestra, the Eroica Quartet Michael Tilson Thomas une 2005 marks the beginning of ATMA’s conducting. -

Le FORUM, Vol. 37 No. 1 Lisa Desjardins Michaud, Rédactrice

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Le FORUM Journal Franco-American Centre Franco-Américain Spring 2014 Le FORUM, Vol. 37 No. 1 Lisa Desjardins Michaud, Rédactrice Guy F. Dubay Roger Parent Harry Rush Jr. Margaret Nagle See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/ francoamericain_forum Recommended Citation Desjardins Michaud, Rédactrice, Lisa; Dubay, Guy F.; Parent, Roger; Rush, Harry Jr.; Nagle, Margaret; Chabot, Greg; Marceau, Albert J.; Nokes, Gary; Gélinas, Alice; Larson, Denise R.; Chartrand, Yves; Riel, Steven; Belleau, Irène; Langford, Margaret S.; LePage, Adrienne Pelletier; and Levesque, Don, "Le FORUM, Vol. 37 No. 1" (2014). Le FORUM Journal. 37. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/francoamericain_forum/37 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Le FORUM Journal by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Lisa Desjardins Michaud, Rédactrice; Guy F. Dubay; Roger Parent; Harry Rush Jr.; Margaret Nagle; Greg Chabot; Albert J. Marceau; Gary Nokes; Alice Gélinas; Denise R. Larson; Yves Chartrand; Steven Riel; Irène Belleau; Margaret S. Langford; Adrienne Pelletier LePage; and Don Levesque This book is available at DigitalCommons@UMaine: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/francoamericain_forum/37 Le“AFIN D’ÊTRE FORUM EN PLEINE POSSESSION DE SES MOYENS” VOLUME 37, #1 -

Theory and Fieldwork John Shepherd and Beverley Diamond

Document generated on 10/01/2021 6:31 a.m. Canadian University Music Review Revue de musique des universités canadiennes Theory and Fieldwork John Shepherd and Beverley Diamond Volume 19, Number 1, 1998 Article abstract John Shepherd URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1014602ar This intervention suggests that the recent and welcome emergence of DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1014602ar fieldwork as a prominent feature of much current work in popular music studies has deflected attention from an undertaking that characterized the See table of contents early days of popular music studies: that of developing from within the various protocols of cultural theory concepts to explain the meanings, significances, and affects that music as a socially and culturally constituted form of human Publisher(s) expression holds for people. In tracing a shift from theoretical to ethnographic concerns in work carried out in popular music studies by musicologists, Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique des universités ethnomusicologists, social anthropologists, and sociologists, it is suggested that canadiennes a renewed emphasis on theory in musicological work in popular music studies may be of consequence for the academic study of music as a whole. ISSN Beverley Diamond 0710-0353 (print) In response to the editor's question concerning theory and fieldwork, this 2291-2436 (digital) colloquy argues that the two are inseparable. Further, the importance of fieldwork in providing "alternative theory" which challenges the consistencies Explore this journal of academic thinking is emphasized. For this reason, the article eschews disciplinary history as a means of tracing important theoretical currents in music scholarship and, instead, presents arguments which confront the hegemonies of any history, any discourse of intellectual continuity, positing Cite this document incidents which expose the social contingencies of theory. -

2013 Performance Showcase Brochure.Pub

10th Annual Performance Showcase November 21, 2013 Lake Morey Resort 1 Clubhouse Road, Fairlee, VT Sponsored by the Vermont Recreation and Parks Association Welcome to the 10th Annual Vermont Recreation & Parks Association Performance Showcase 2013 Showcase Committee Members John Leonard - Hartland Recreation Department Carol Lolatte - Brattleboro Recreation & Parks Department Ray Sapp - Hartland Recreation Department Betsy Terry Orselet - VRPA Executive Director Jennifer Turmel - Colchester Parks & Recreation Sit back, relax, and enjoy a sample of some of New England’s finest performers! www.vrpa.org 1 Artist Listing - Alphabetical Artist/Group ____________ Page Andrew Pinard/Absolutely Magic Exhibitor: Magician 16 Andrew Salgado Showcase: Country Singer/Songwriter 12 Arts are Essential, Inc Exhibitor: Professional Art-Educators 16 Bill Shontz Showcase: Music for All Ages 8 Bryson Lang Showcase: Comedy/Juggling 14 Buddy the Clown Exhibitor: Clown/ Magic 16 Celia Slattery Booklet Listing Only: Jazz and Pop 21 Chris Yerlig Showcase: Mime & Magic Illusionist 12 Dana And Friends Exhibitor: Ventriloquist/Magician 17 Drumming About You Booklet Listing Only: Drumming 20 Eat Like a Rainbow/Jay Mankita Showcase: Children’s Music 6 Ed the Wizard Exhibitor: Magician 17 Eli Elkus Showcase: Singer/Songwriter 15 Fizzical Fairytales Showcase: Theatre, Circus, Songs, & Magic 5 Full Circle Showcase: World Folk 13 Green Mountain Chorus Showcase: Barbershop 13 Jessica Prouty Band Showcase: Family-Friendly Rock Band 12 Jim Gallant Showcase: Singer/Songwriter -

Box File No. Title Location Aca

BOX FILE NO. TITLE LOCATION A.C.A. Newsletter. Alberta Composers' Association Newsletter. Alberta A.S.O. Atlantic Symphony Orchestra. Newfoundland, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia …. Nova Scotia …. [Atlantic Provinces] A Benefit Concert for Women's College Hospital. John Arpin, [Pianist.]. Women's College Hospital 75th Anniversary, Toronto. 1911-1986. Roy Thomson Hall, Toronto. 1 1 A Space - Toronto. Toronto 1 2 L'Acadamie Des Lettres Et Des Sciences Humaine de la Society Royal Du Canada. [Ottawa?] 1 3 Academy of Dance. [Brantford, Ontario?] Acadia University. Wolfville, Nova Scotia. Nova Scotia 1 4 ACME Theatre Company. Toronto Acting Company. Toronto. Toronto 1 5 The Actors Workshop. Toronto. Toronto John Adams. New Music for synthesizers, solo bass and grand pianos by John Adams & Chan Ka Nin. Premiere Dance Toronto. Theatre. New Music Concert. [Toronto.] 1 6 Adelaide Court Theatre. Toronto. Toronto 1 7 The Aeolian Town Hall. The London School Of Church Music. A Concert to honour the Silver Jubilee of Her Majesty London, Ontario Queen Elizabeth II. 1 8 Aetna Canada Young People's Concerts. Toronto. Toronto African Theatre Ensemble. Toronto 1 9 AfriCanadian Playwrights Festival. Toronto. Toronto 1 10 Agnes Etherington Art Centre, Kingston. Kingston Aid to Artists. The Canada Council, 1978-79. Ottawa. Ottawa Air Command Band. Winnipeg 1 11 Alberta College. Alberta The Alberta Music Conference. Banff School of Fine Arts. Alberta 1 12 The Aldeburgh Connection. Concert Society. Toronto. Toronto Lenore Alford, orgue. Conseil Des Arts et Des Lettres Du Quebec. Quebec 1 13 Algoma Fall Festival. Saulte Ste. Marie, Ontario. Saulte Ste. Marie, Ontario Alianak Theatre.