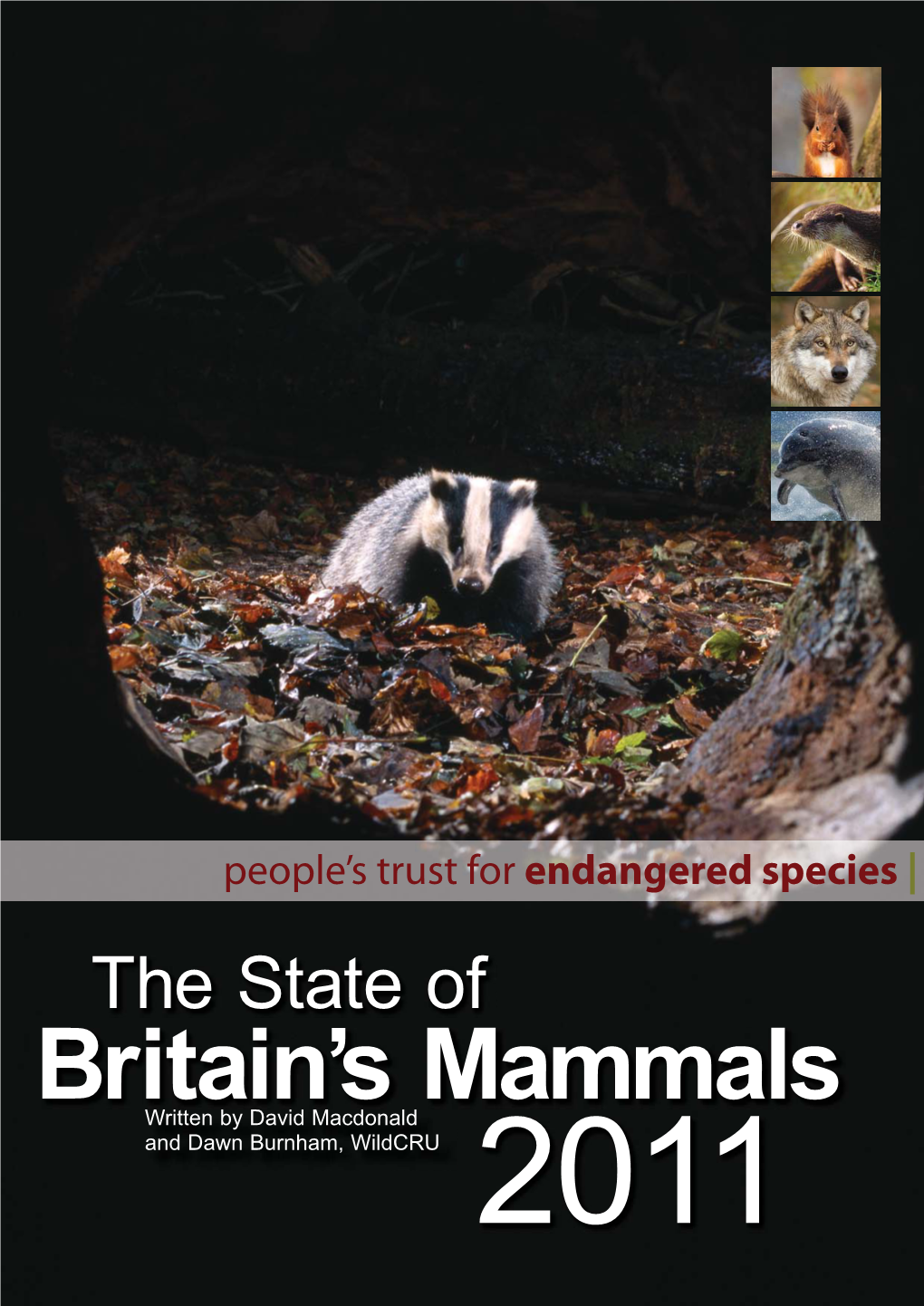

State of Britain's Mammals 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 Cruise Directory

Despite the modern fashion for large floating resorts, we b 7 nights 0 2019 CRUISE DIRECTORY Highlands and Islands of Scotland Orkney and Shetland Northern Ireland and The Isle of Man Cape Wrath Scrabster SCOTLAND Kinlochbervie Wick and IRELAND HANDA ISLAND Loch a’ FLANNAN Stornoway Chàirn Bhain ISLES LEWIS Lochinver SUMMER ISLES NORTH SHIANT ISLES ST KILDA Tarbert SEA Ullapool HARRIS Loch Ewe Loch Broom BERNERAY Trotternish Inverewe ATLANTIC NORTH Peninsula Inner Gairloch OCEAN UIST North INVERGORDON Minch Sound Lochmaddy Uig Shieldaig BENBECULA Dunvegan RAASAY INVERNESS SKYE Portree Loch Carron Loch Harport Kyle of Plockton SOUTH Lochalsh UIST Lochboisdale Loch Coruisk Little Minch Loch Hourn ERISKAY CANNA Armadale BARRA RUM Inverie Castlebay Sound of VATERSAY Sleat SCOTLAND PABBAY EIGG MINGULAY MUCK Fort William BARRA HEAD Sea of the Glenmore Loch Linnhe Hebrides Kilchoan Bay Salen CARNA Ballachulish COLL Sound Loch Sunart Tobermory Loch à Choire TIREE ULVA of Mull MULL ISLE OF ERISKA LUNGA Craignure Dunsta!nage STAFFA OBAN IONA KERRERA Firth of Lorn Craobh Haven Inveraray Ardfern Strachur Crarae Loch Goil COLONSAY Crinan Loch Loch Long Tayvallich Rhu LochStriven Fyne Holy Loch JURA GREENOCK Loch na Mile Tarbert Portavadie GLASGOW ISLAY Rothesay BUTE Largs GIGHA GREAT CUMBRAE Port Ellen Lochranza LITTLE CUMBRAE Brodick HOLY Troon ISLE ARRAN Campbeltown Firth of Clyde RATHLIN ISLAND SANDA ISLAND AILSA Ballycastle CRAIG North Channel NORTHERN Larne IRELAND Bangor ENGLAND BELFAST Strangford Lough IRISH SEA ISLE OF MAN EIRE Peel Douglas ORKNEY and Muckle Flugga UNST SHETLAND Baltasound YELL Burravoe Lunna Voe WHALSAY SHETLAND Lerwick Scalloway BRESSAY Grutness FAIR ISLE ATLANTIC OCEAN WESTRAY SANDAY STRONSAY ORKNEY Kirkwall Stromness Scapa Flow HOY Lyness SOUTH RONALDSAY NORTH SEA Pentland Firth STROMA Scrabster Caithness Wick Welcome to the 2019 Hebridean Princess Cruise Directory Unlike most cruise companies, Hebridean operates just one very small and special ship – Hebridean Princess. -

Anne R Johnston Phd Thesis

;<>?3 ?3@@8393;@ 6; @53 6;;3> 530>623? 1/# *%%"&(%%- B6@5 ?=316/8 >343>3;13 @< @53 6?8/;2? <4 9A88! 1<88 /;2 @6>33 /OOG ># 7PJOSTPO / @JGSKS ?UDNKTTGF HPR TJG 2GIRGG PH =J2 CT TJG AOKVGRSKTY PH ?T# /OFRGWS &++& 4UMM NGTCFCTC HPR TJKS KTGN KS CVCKMCDMG KO >GSGCREJ.?T/OFRGWS,4UMM@GXT CT, JTTQ,$$RGSGCREJ"RGQPSKTPRY#ST"COFRGWS#CE#UL$ =MGCSG USG TJKS KFGOTKHKGR TP EKTG PR MKOL TP TJKS KTGN, JTTQ,$$JFM#JCOFMG#OGT$&%%'($'+)% @JKS KTGN KS QRPTGETGF DY PRKIKOCM EPQYRKIJT Norse settlement in the Inner Hebrides ca 800-1300 with special reference to the islands of Mull, Coll and Tiree A thesis presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Anne R Johnston Department of Mediaeval History University of St Andrews November 1990 IVDR E A" ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS None of this work would have been possible without the award of a studentship from the University of &Andrews. I am also grateful to the British Council for granting me a scholarship which enabled me to study at the Institute of History, University of Oslo and to the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs for financing an additional 3 months fieldwork in the Sunnmore Islands. My sincere thanks also go to Prof Ragni Piene who employed me on a part time basis thereby allowing me to spend an additional year in Oslo when I was without funding. In Norway I would like to thank Dr P S Anderson who acted as my supervisor. Thanks are likewise due to Dr H Kongsrud of the Norwegian State Archives and to Dr T Scmidt of the Place Name Institute, both of whom were generous with their time. -

2020 Cruise Directory Directory 2020 Cruise 2020 Cruise Directory M 18 C B Y 80 −−−−−−−−−−−−−−− 17 −−−−−−−−−−−−−−−

2020 MAIN Cover Artwork.qxp_Layout 1 07/03/2019 16:16 Page 1 2020 Hebridean Princess Cruise Calendar SPRING page CONTENTS March 2nd A Taste of the Lower Clyde 4 nights 22 European River Cruises on board MS Royal Crown 6th Firth of Clyde Explorer 4 nights 24 10th Historic Houses and Castles of the Clyde 7 nights 26 The Hebridean difference 3 Private charters 17 17th Inlets and Islands of Argyll 7 nights 28 24th Highland and Island Discovery 7 nights 30 Genuinely fully-inclusive cruising 4-5 Belmond Royal Scotsman 17 31st Flavours of the Hebrides 7 nights 32 Discovering more with Scottish islands A-Z 18-21 Hebridean’s exceptional crew 6-7 April 7th Easter Explorer 7 nights 34 Cruise itineraries 22-97 Life on board 8-9 14th Springtime Surprise 7 nights 36 Cabins 98-107 21st Idyllic Outer Isles 7 nights 38 Dining and cuisine 10-11 28th Footloose through the Inner Sound 7 nights 40 Smooth start to your cruise 108-109 2020 Cruise DireCTOrY Going ashore 12-13 On board A-Z 111 May 5th Glorious Gardens of the West Coast 7 nights 42 Themed cruises 14 12th Western Isles Panorama 7 nights 44 Highlands and islands of scotland What you need to know 112 Enriching guest speakers 15 19th St Kilda and the Outer Isles 7 nights 46 Orkney, Northern ireland, isle of Man and Norway Cabin facilities 113 26th Western Isles Wildlife 7 nights 48 Knowledgeable guides 15 Deck plans 114 SuMMER Partnerships 16 June 2nd St Kilda & Scotland’s Remote Archipelagos 7 nights 50 9th Heart of the Hebrides 7 nights 52 16th Footloose to the Outer Isles 7 nights 54 HEBRIDEAN -

Annual Report

ECTF Edinburgh Centre for Tropical Forests School of GeoSciences CECS/Crew Building, Kings Buildings, University of Edinburgh, http://www.darwin.gov.uk West Mains Rd, Edinburgh EH9 3JN, UK [email protected] Tel: +44 (0)131 650 7862 Darwin Initiative Annual Report 1. Darwin Project Information Project Ref. Number 14-028 Project Title Conservation of Puna’s Andean cats across national borders Country(ies) Argentina, Bolivia and Chile UK Contractor Wildlife Conservation Research Unit (WildCRU), Oxford University Partner Organisation(s) Andean Cat Alliance (AGA); Mammal Behavioural Ecology Group, Universidad Nacional del Sur (Argentina); Museo de Ciencias Naturales de Salta, Universidad Nacional de Salta (Argentina); Colección Boliviana de Fauna (Bolivia); Fundación Biodiversitas (Chile); Universidad de Chile, Universidad Mayor, Universidad Catolica (Chile); Wildlife Conservation Network (USA) Darwin Grant Value £159,186 Start/End dates 01 October 2005 – 30 September 2008 Reporting period 1 Oct 2005 to 30 Apr 2006, Annual report # 1 Project website www.wildcru.org/andeancat Author(s), date Claudio Sillero-Zubiri, Mauro Lucherini, María José Merino and Jorgelina Marino; 30 April 2006 1 Project annual report format Feb 2006 2. Project Background The Andean cat (Oreailurus jacobita) is the rarest South American felid, and one of the most endangered wild cats in the world. Endemic to the Central High Andes, this carnivore is a specialized predator of a community of high altitude vertebrates and can be used as a flagship species for the conservation of the Puna’s endemic-rich biodiversity. Our work is centred on the triple frontier of Argentina, Bolivia and Chile, a remote region where most recent Andean cat sightings have occurred and with existing adjacent conservation areas in all three countries. -

Hedgehog Fact Sheet

Hedgehog Descrip�on: This par�cular hedgehog and called a Four-toed hedgehog. The Four-toed hedgehog only has 4 toes on each hind foot. The hedgehog has a very dis�nc�ve prickly spiny coat and long coarse hair on its face and underparts. An adult hedgehog can grow between 14 to 30 cen�meters long. Females are larger than males. Habitat: Class: Mammalia The four-toed hedgehog is found across central Africa. Order: Eulipotyphla They prefer grassy environments or open woodland Family: Erinaceidae with eleva�ons as high a 6,600 �. Their main predators Genus & Species: Erinaceus are Verreaux’s eagles, owls, jackals, hyenas and honey badgers. They prefer temperatures in the mid Life Span: up to 3 years in wild and up to 10 80’s F. When the hot dry season occurs and food is in cap�vity scarce they will go into a state of aes�va�on - inac�vity and lowered metabolic rate and when the temperature Fun Facts: gets colder it will go into a state of hiberna�on. Hedghogs rarely lose their quills during adulthood. Adapta�ons: Hedgehogs sleep in rolled up in a ball to protect The four-toed hedgehog is a solitary, nocturnal animal themselves. normally found along the ground. They have a high They have a special circular muscle that runs tolerance for toxins and have been known to eat along the sides of its body and across its neck scorpions and venomous snakes. When a�acked by and bo�om. When this muscle contracts it a predator, it can scream loudly. -

Mammals of Jordan

© Biologiezentrum Linz/Austria; download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Mammals of Jordan Z. AMR, M. ABU BAKER & L. RIFAI Abstract: A total of 78 species of mammals belonging to seven orders (Insectivora, Chiroptera, Carni- vora, Hyracoidea, Artiodactyla, Lagomorpha and Rodentia) have been recorded from Jordan. Bats and rodents represent the highest diversity of recorded species. Notes on systematics and ecology for the re- corded species were given. Key words: Mammals, Jordan, ecology, systematics, zoogeography, arid environment. Introduction In this account we list the surviving mammals of Jordan, including some reintro- The mammalian diversity of Jordan is duced species. remarkable considering its location at the meeting point of three different faunal ele- Table 1: Summary to the mammalian taxa occurring ments; the African, Oriental and Palaearc- in Jordan tic. This diversity is a combination of these Order No. of Families No. of Species elements in addition to the occurrence of Insectivora 2 5 few endemic forms. Jordan's location result- Chiroptera 8 24 ed in a huge faunal diversity compared to Carnivora 5 16 the surrounding countries. It shelters a huge Hyracoidea >1 1 assembly of mammals of different zoogeo- Artiodactyla 2 5 graphical affinities. Most remarkably, Jordan Lagomorpha 1 1 represents biogeographic boundaries for the Rodentia 7 26 extreme distribution limit of several African Total 26 78 (e.g. Procavia capensis and Rousettus aegypti- acus) and Palaearctic mammals (e. g. Eri- Order Insectivora naceus concolor, Sciurus anomalus, Apodemus Order Insectivora contains the most mystacinus, Lutra lutra and Meles meles). primitive placental mammals. A pointed snout and a small brain case characterises Our knowledge on the diversity and members of this order. -

Argyll & the Isles

EXPLORE 2020-2021 ARGYLL & THE ISLES Earra-Ghàidheal agus na h-Eileanan visitscotland.com Contents The George Hotel 2 Argyll & The Isles at a glance 4 Scotland’s birthplace 6 Wild forests and exotic gardens 8 Island hopping 10 Outdoor playground 12 Natural larder 14 Year of Coasts and Waters 2020 16 What’s on 18 Travel tips 20 Practical information 24 Places to visit 38 Leisure activities 40 Shopping Welcome to… 42 Food & drink 46 Tours ARGYLL 49 Transport “Classic French Cuisine combined with & THE ISLES 49 Events & festivals Fáilte gu Earra-Gháidheal ’s 50 Accommodation traditional Scottish style” na h-Eileanan 60 Regional map Extensive wine and whisky selection, Are you ready to fall head over heels in love? In Argyll & The Isles, you’ll find gorgeous scenery, irresistible cocktails and ales, quirky bedrooms and history and tranquil islands. This beautiful region is Scotland’s birthplace and you’ll see castles where live music every weekend ancient kings were crowned and monuments that are among the oldest in the UK. You should also be ready to be amazed by our incredibly Cover: Crinan Canal varied natural wonders, from beavers Above image: Loch Fyne and otters to minke whales and sea eagles. Credits: © VisitScotland. Town Hotel of the Year 2018 Once you’ve started exploring our Kenny Lam, Stuart Brunton, fascinating coast and hopping around our dozens of islands you might never Wild About Argyll / Kieran Duncan, want to stop. It’s time to be smitten! Paul Tomkins, John Duncan, Pub of the Year 2019 Richard Whitson, Shane Wasik/ Basking Shark Scotland, Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh / Bar Dining Hotel of the Year 2019 Peter Clarke 20ARS Produced and published by APS Group Scotland (APS) in conjunction with VisitScotland (VS) and Highland News & Media (HNM). -

The Clan Macneil

THE CLAN MACNEIL CLANN NIALL OF SCOTLAND By THE MACNEIL OF BARRA Chief of the Clan Fellow of the Society of .Antiquarie1 of Scotland With an Introduction by THE DUKE OF ARGYLL Chief of Clan Campbell New York THE CALEDONIAN PUBLISHING COMPANY MCMXXIII Copyright, 1923, by THE CALEDONIAN PUBLISHING COMPANY Entered at Stationers~ Hall, London, England .All rights reser:ved Printed by The Chauncey Holt Compan}'. New York, U. 5. A. From Painting by Dr. E, F. Coriu, Paris K.1s11\1 UL CASTLE} IsLE OF BAH HA PREFACE AVING a Highlander's pride of race, it was perhaps natural that I should have been deeply H interested, as a lad, in the stirring tales and quaint legends of our ancient Clan. With maturity came the desire for dependable records of its history, and I was disappointed at finding only incomplete accounts, here and there in published works, which were at the same time often contradictory. My succession to the Chiefship, besides bringing greetings from clansmen in many lands, also brought forth their expressions of the opinion that a complete history would be most desirable, coupled with the sug gestion that, as I had considerable data on hand, I com pile it. I felt some diffidence in undertaking to write about my own family, but, believing that under these conditions it would serve a worthy purpose, I commenced this work which was interrupted by the chaos of the Great War and by my own military service. In all cases where the original sources of information exist I have consulted them, so that I believe the book is quite accurate. -

Differential Loss of Embryonic Globin Genes During the Radiation of Placental Mammals

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Jay F. Storz Publications Papers in the Biological Sciences 9-2-2008 Differential loss of embryonic globin genes during the radiation of placental mammals Juan C. Opazo Instituto de Ecología y Evolución, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Austral de Chile, Casilla 567, Valdivia, Chile Federico Hoffmann Instituto Carlos Chagas Fiocruz, Rua Prof. Algacyr Munhoz Mader 3775-CIC, 81350-010, Curitiba, Brazil Jay F. Storz University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/bioscistorz Part of the Genetics and Genomics Commons Opazo, Juan C.; Hoffmann, Federico; and Storz, Jay F., "Differential loss of embryonic globin genes during the radiation of placental mammals" (2008). Jay F. Storz Publications. 26. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/bioscistorz/26 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Jay F. Storz Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 105:35 (September 2, 2008), pp. 12950–12955; doi 10.1073/pnas.0804392105 Copyright © 2008 by The National Academy of Sciences of the USA. Used by permission. http://www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.0804392105 Author contributions: J.C.O. and J.F.S. designed research; J.C.O. and F.G.H. performed research; J.C.O. and F.G.H. analyzed data; and J.C.O. and J.F.S. wrote the paper. -

Activity of the European Mole Talpa Europaea (Talpidae, Insectivora) in Its Burrows in the Republic of Mordovia

FORESTRY IDEAS, 2021, vol. 27, No 1 (61): 59–67 ACTIVITY OF THE EUROPEAN MOLE TALPA EUROPAEA (TALPIDAE, INSECTIVORA) IN ITS BURROWS IN THE REPUBLIC OF MORDOVIA Alexey Andreychev Department of Zoology, National Research Mordovia State University, Saransk 430005, Russia. E-mail: [email protected] Received: 16 February 2021 Accepted: 18 April 2021 Abstract A new method of studying the activity of European mole Talpa europaea (Linnaeus, 1758) with use of digital portable voice recorders is developed. European mole demonstrates polyphasic activity pattern – three peaks of activity alternate three peaks of relative rest. Moles are found to have activity peaks from 23:00 to 3:00 h, from 6:00 to 9:00 h and from 15:00 to 18:00 h, and three periods of rest: from 3:00 to 6:00 h, from 9:00 to 15:00 h and from 18:00 to 23:00 h. Mole’s rest is relative since animals show low activity during periods of rest. Average daily interval between mole passes is 2.5 h. Duration of audibility of continuous single European mole pass by the mi- crophone varies from 11 to 120 seconds. On average, it is 37.5 seconds. Key words: animals, daily activity, day-night activity, voice recorder. Introduction where light factor is essential (Shilov 2001). Activity of many mammals is in- In many countries, the European mole Tal- vestigated under various conditions of the pa europaea (Linnaeus, 1758) is an object light regime. For underground animals, of constant modern research (Komarnicki especially for the different mole species, 2000, Prochel 2006, Kang et al. -

Subterranean Mammals Show Convergent Regression in Ocular Genes and Enhancers, Along with Adaptation to Tunneling

RESEARCH ARTICLE Subterranean mammals show convergent regression in ocular genes and enhancers, along with adaptation to tunneling Raghavendran Partha1, Bharesh K Chauhan2,3, Zelia Ferreira1, Joseph D Robinson4, Kira Lathrop2,3, Ken K Nischal2,3, Maria Chikina1*, Nathan L Clark1* 1Department of Computational and Systems Biology, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, United States; 2UPMC Eye Center, Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, United States; 3Department of Ophthalmology, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, United States; 4Department of Molecular and Cell Biology, University of California, Berkeley, United States Abstract The underground environment imposes unique demands on life that have led subterranean species to evolve specialized traits, many of which evolved convergently. We studied convergence in evolutionary rate in subterranean mammals in order to associate phenotypic evolution with specific genetic regions. We identified a strong excess of vision- and skin-related genes that changed at accelerated rates in the subterranean environment due to relaxed constraint and adaptive evolution. We also demonstrate that ocular-specific transcriptional enhancers were convergently accelerated, whereas enhancers active outside the eye were not. Furthermore, several uncharacterized genes and regulatory sequences demonstrated convergence and thus constitute novel candidate sequences for congenital ocular disorders. The strong evidence of convergence in these species indicates that evolution in this environment is recurrent and predictable and can be used to gain insights into phenotype–genotype relationships. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.25884.001 *For correspondence: [email protected] (MC); [email protected] (NLC) Competing interests: The Introduction authors declare that no The subterranean habitat has been colonized by numerous animal species for its shelter and unique competing interests exist. -

Solenodon Genome Reveals Convergent Evolution of Venom in Eulipotyphlan Mammals

Solenodon genome reveals convergent evolution of venom in eulipotyphlan mammals Nicholas R. Casewella,1, Daniel Petrasb,c, Daren C. Cardd,e,f, Vivek Suranseg, Alexis M. Mychajliwh,i,j, David Richardsk,l, Ivan Koludarovm, Laura-Oana Albulescua, Julien Slagboomn, Benjamin-Florian Hempelb, Neville M. Ngumk, Rosalind J. Kennerleyo, Jorge L. Broccap, Gareth Whiteleya, Robert A. Harrisona, Fiona M. S. Boltona, Jordan Debonoq, Freek J. Vonkr, Jessica Alföldis, Jeremy Johnsons, Elinor K. Karlssons,t, Kerstin Lindblad-Tohs,u, Ian R. Mellork, Roderich D. Süssmuthb, Bryan G. Fryq, Sanjaya Kuruppuv,w, Wayne C. Hodgsonv, Jeroen Kooln, Todd A. Castoed, Ian Barnesx, Kartik Sunagarg, Eivind A. B. Undheimy,z,aa, and Samuel T. Turveybb aCentre for Snakebite Research & Interventions, Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, Pembroke Place, L3 5QA Liverpool, United Kingdom; bInstitut für Chemie, Technische Universität Berlin, 10623 Berlin, Germany; cCollaborative Mass Spectrometry Innovation Center, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92093; dDepartment of Biology, University of Texas at Arlington, Arlington, TX 76010; eDepartment of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138; fMuseum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138; gEvolutionary Venomics Lab, Centre for Ecological Sciences, Indian Institute of Science, 560012 Bangalore, India; hDepartment of Biology, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305; iDepartment of Rancho La Brea, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Los Angeles,