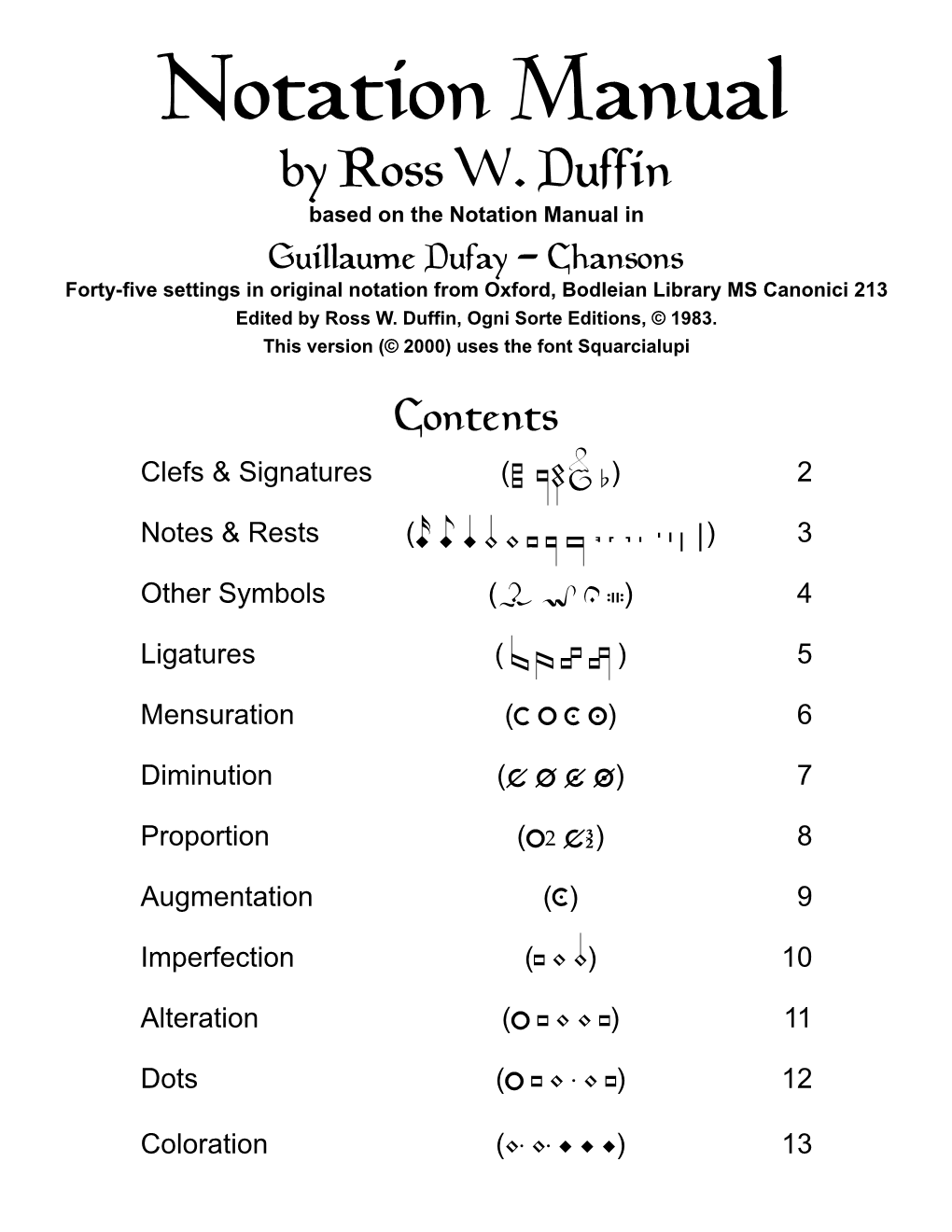

Notation Manual by Ross W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dynamic Generation of Musical Notation from Musicxml Input on an Android Tablet

Dynamic Generation of Musical Notation from MusicXML Input on an Android Tablet THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Laura Lynn Housley Graduate Program in Computer Science and Engineering The Ohio State University 2012 Master's Examination Committee: Rajiv Ramnath, Advisor Jayashree Ramanathan Copyright by Laura Lynn Housley 2012 Abstract For the purpose of increasing accessibility and customizability of sheet music, an application on an Android tablet was designed that generates and displays sheet music from a MusicXML input file. Generating sheet music on a tablet device from a MusicXML file poses many interesting challenges. When a user is allowed to set the size and colors of an image, the image must be redrawn with every change. Instead of zooming in and out on an already existing image, the positions of the various musical symbols must be recalculated to fit the new dimensions. These changes must preserve the relationships between the various musical symbols. Other topics include the laying out and measuring of notes, accidentals, beams, slurs, and staffs. In addition to drawing a large bitmap, an application that effectively presents sheet music must provide a way to scroll this music across a small tablet screen at a specified tempo. A method for using animation on Android is discussed that accomplishes this scrolling requirement. Also a generalized method for writing text-based documents to describe notations similar to musical notation is discussed. This method is based off of the knowledge gained from using MusicXML. -

The New Dictionary of Music and Musicians

The New GROVE Dictionary of Music and Musicians EDITED BY Stanley Sadie 12 Meares - M utis London, 1980 376 Moda Harold Powers Mode (from Lat. modus: 'measure', 'standard'; 'manner', 'way'). A term in Western music theory with three main applications, all connected with the above meanings of modus: the relationship between the note values longa and brevis in late medieval notation; interval, in early medieval theory; most significantly, a concept involving scale type and melody type. The term 'mode' has always been used to designate classes of melodies, and in this century to designate certain kinds of norm or model for composition or improvisation as well. Certain pheno mena in folksong and in non-Western music are related to this last meaning, and are discussed below in §§IV and V. The word is also used in acoustical parlance to denote a particular pattern of vibrations in which a system can oscillate in a stable way; see SOUND, §5. I. The term. II. Medieval modal theory. III. Modal theo ries and polyphonic music. IV. Modal scales and folk song melodies. V. Mode as a musicological concept. I. The term I. Mensural notation. 2. Interval. 3. Scale or melody type. I. MENSURAL NOTATION. In this context the term 'mode' has two applications. First, it refers in general to the proportional durational relationship between brevis and /onga: the modus is perfectus (sometimes major) when the relationship is 3: l, imperfectus (sometimes minor) when it is 2 : I. (The attributives major and minor are more properly used with modus to distinguish the rela tion of /onga to maxima from the relation of brevis to longa, respectively.) In the earliest stages of mensural notation, the so called Franconian notation, 'modus' designated one of five to seven fixed arrangements of longs and breves in particular rhythms, called by scholars rhythmic modes. -

The Musical Notation and Rhythm of the Italian Laude *

26 THE MUSICAL NOTATION AND RHYTHM OF THE ITALIAN LAUDE * Thc Typical Italian Charactcr oj tfzc Laudc. When we study the musical repertoire of the Medievallaude 1, we find a situation qui te different from that of Provençal, French, or Spanish lyric poetry and from that of the German minnesingers. In Italy, there existed a repertoire of rcligious songs in the verna cular language dedicated to Christ, Our Lady, and the various Saints, generally anonymous, and composed far the use of the faithful of the confraternita - something unknown in other countries. By vir tue of the literary subjects of their texts, by their melodies, and by thei r musical notation, these laude became, in the eyes of the world, a manifestation of a very pronounced Italian artistic indivi duality. In the repertoire of lyric monody of other European countries, we fmd certain melodies of a traditional, popular vein which remind us of others - international ones. In the laude, on the other hand, this similarity to international tunes is absent; they are exclusively national in character. It is, in fact, remarkable that the laude reflect no melodie analogies with either international folklore or with the profane or religious lyric poetry of other European countries. In examining the Italian lauda repertoire, the first things to claim our attention in the music are its simple style and its popular charac- • Publishcd in Essays i11 Musicology . A Birthday O.fferi11g far Willi Ape/. Hms Tischler, Ed. Indiana Univcrsity, Bloomington (Indiana 1968), 56-6o. From the samc author sce also Las Laudi italianas de los siglos XIII y XIV. -

New International Manual of Braille Music Notation by the Braille Music Subcommittee World Blind Union

1 New International Manual Of Braille Music Notation by The Braille Music Subcommittee World Blind Union Compiled by Bettye Krolick ISBN 90 9009269 2 1996 2 Contents Preface................................................................................ 6 Official Delegates to the Saanen Conference: February 23-29, 1992 .................................................... 8 Compiler’s Notes ............................................................... 9 Part One: General Signs .......................................... 11 Purpose and General Principles ..................................... 11 I. Basic Signs ................................................................... 13 A. Notes and Rests ........................................................ 13 B. Octave Marks ............................................................. 16 II. Clefs .............................................................................. 19 III. Accidentals, Key & Time Signatures ......................... 22 A. Accidentals ................................................................ 22 B. Key & Time Signatures .............................................. 22 IV. Rhythmic Groups ....................................................... 25 V. Chords .......................................................................... 30 A. Intervals ..................................................................... 30 B. In-accords .................................................................. 34 C. Moving-notes ............................................................ -

Dictionary of Braille Music Signs by Bettye Krolick

JBN 0-8444-0 9 C D E F G Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from National Federation of the Blind (NFB) http://archive.org/details/dictionaryofbraiOObett LIBRARY IOWA DEPARTMENT FOR THE BLIND 524 Fourth Street Des Moines, Iowa 50309-2364 Dictionary of Braille Music Signs by Bettye Krolick National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 20542 1979 MT. PLEASANT HIGH SCHOOL LIBRARY Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Krolick, Bettye. Dictionary of braille music signs. At head of title: National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped, Library of Congress. Bibliography: p. 182-188 Includes index. 1. Braille music-notation. I. National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped. II. Title. MT38.K76 78L.24 78-21301 ISBN 0-8444-0277-X . TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD vii PREFACE ix HISTORY OF THE BRAILLE MUSIC CODE ... xi HOW TO LOCATE A DEFINITION xviii DICTIONARY OF SIGNS (A sign that contains two or more cells is listed under its first character.) . 1 •* 1 •• 16 • • •• 3 •• 17 •> 6 •• 17 •• •• 7 •• 17 •• 7 •• 17 •• •• 7 •• 17 •• •• 8 •• 18 •• •• 8 •• 18 •• •• 9 •• 19 •• •• 9 •• 19 • • •• 10 •• 20 • • •• 12 •• 20 •• 14 •• 20 •• •• 14 •• 22 • • •• •• 15 • • 27 •• •• •« •• 15 • • 29 •• • • •« 16 30 •• •• 16 • • 30 30 i: 46 ?: 31 11 47 r. 31 ;: 48 •: 31 i? 58 ?: 31 i; 78 ::' 34 :: 79 a 34 ;: si 35 ;? 86 37 ;: 90 39 ':• 96 40 ;: 102 43 i: 105 45 ;: 113 46 FORMATS FOR BRAILLE MUSIC 122 Format Identification Chart 125 Music in Parallels -

Composers' Bridge!

Composers’ Bridge Workbook Contents Notation Orchestration Graphic notation 4 Orchestral families 43 My graphic notation 8 Winds 45 Clefs 9 Brass 50 Percussion 53 Note lengths Strings 54 Musical equations 10 String instrument special techniques 59 Rhythm Voice: text setting 61 My rhythm 12 Voice: timbre 67 Rhythmic dictation 13 Tips for writing for voice 68 Record a rhythm and notate it 15 Ideas for instruments 70 Rhythm salad 16 Discovering instruments Rhythm fun 17 from around the world 71 Pitch Articulation and dynamics Pitch-shape game 19 Articulation 72 Name the pitches – part one 20 Dynamics 73 Name the pitches – part two 21 Score reading Accidentals Muddling through your music 74 Piano key activity 22 Accidental practice 24 Making scores and parts Enharmonics 25 The score 78 Parts 78 Intervals Common notational errors Fantasy intervals 26 and how to catch them 79 Natural half steps 27 Program notes 80 Interval number 28 Score template 82 Interval quality 29 Interval quality identification 30 Form Interval quality practice 32 Form analysis 84 Melody Rehearsal and concert My melody 33 Presenting your music in front Emotion melodies 34 of an audience 85 Listening to melodies 36 Working with performers 87 Variation and development Using the computer Things you can do with a Computer notation: Noteflight 89 musical idea 37 Sound exploration Harmony My favorite sounds 92 Harmony basics 39 Music in words and sentences 93 Ear fantasy 40 Word painting 95 Found sound improvisation 96 Counterpoint Found sound composition 97 This way and that 41 Listening journal 98 Chord game 42 Glossary 99 Welcome Dear Student and family Welcome to the Composers' Bridge! The fact that you are being given this book means that we already value you as a composer and a creative artist-in-training. -

The Development of Musical Notation Carolyn S

Cedarville University DigitalCommons@Cedarville The Research and Scholarship Symposium The 2015 yS mposium Apr 1st, 2:20 PM - 2:40 PM Slashes, Dashes, Points, and Squares: The Development of Musical Notation Carolyn S. Gorog Cedarville University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/ research_scholarship_symposium Part of the Composition Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Gorog, Carolyn S., "Slashes, Dashes, Points, and Squares: The eD velopment of Musical Notation" (2015). The Research and Scholarship Symposium. 5. http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/research_scholarship_symposium/2015/podium_presentations/5 This Podium Presentation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Cedarville, a service of the Centennial Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Research and Scholarship Symposium by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Cedarville. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Slashes, Dashes, Points, and Squares: The development of Musical Notation Slashes, Dashes, Points, and Squares: The Development of Musical Notation Music has been around for a long time; in almost every culture around the world we find evidence of music. Music throughout history started as mostly vocal music, it was transmitted orally with no written notation. During the early ninth and tenth century the written tradition started to be seen and developed. This marked the beginnings of music notation. Music notation has gone through many stages of development from neumes, square notes, and four-line staff, to modern notation. Although modern notation works very well, it is not necessarily superior to methods used in the Renaissance and Medieval periods. In Western music neumes are the name given to the first type of notation used. -

Andrián Pertout

Andrián Pertout Three Microtonal Compositions: The Utilization of Tuning Systems in Modern Composition Volume 1 Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Produced on acid-free paper Faculty of Music The University of Melbourne March, 2007 Abstract Three Microtonal Compositions: The Utilization of Tuning Systems in Modern Composition encompasses the work undertaken by Lou Harrison (widely regarded as one of America’s most influential and original composers) with regards to just intonation, and tuning and scale systems from around the globe – also taking into account the influential work of Alain Daniélou (Introduction to the Study of Musical Scales), Harry Partch (Genesis of a Music), and Ben Johnston (Scalar Order as a Compositional Resource). The essence of the project being to reveal the compositional applications of a selection of Persian, Indonesian, and Japanese musical scales utilized in three very distinct systems: theory versus performance practice and the ‘Scale of Fifths’, or cyclic division of the octave; the equally-tempered division of the octave; and the ‘Scale of Proportions’, or harmonic division of the octave championed by Harrison, among others – outlining their theoretical and aesthetic rationale, as well as their historical foundations. The project begins with the creation of three new microtonal works tailored to address some of the compositional issues of each system, and ending with an articulated exposition; obtained via the investigation of written sources, disclosure -

From Neumes to Notation: a Thousand Years of Passing on the Music by Charric Van Der Vliet

From Neumes to Notation: A Thousand Years of Passing On the Music by Charric Van der Vliet Classical musicians, in the terminology of the 17th and 18th century musical historians, like to sneer at earlier music as "primitive", "rough", or "uncouth". The fact of the matter is that during the thousand years from 450 AD to about 1450 AD, Western Civilization went from no recording of music at all to a fully formed method of passing on the most intricate polyphony. That is no small achievement. It's attractive, I suppose, to assume the unthinking and barbaric nature of our ancestors, since it implies a certain smugness about "how far we've come." I've always thought that painting your ancestors as stupid was insulting both to them and to yourself. The barest outline of a thousand year journey only hints at the difficulties our medieval ancestors had to face to be musical. This is an attempt at sketching that outline. Each of the sub-headings of this lecture contains material for lifetimes of musical study. It is hoped that outlining this territory may help shape where your own interests will ultimately lie. Neumes: In the beginning, choristers needed reminders as to which way notes went. "That fifth note goes DOWN, George!" This situation was remedied by noting when the movement happened and what direction, above the text, with wavy lines. "Neume" was the adopted term for this. It's a Middle English corruption of the Greek word for breath, "pneuma." Then, to specify note's exact pitch was the next innovation. -

Music Braille Code, 2015

MUSIC BRAILLE CODE, 2015 Developed Under the Sponsorship of the BRAILLE AUTHORITY OF NORTH AMERICA Published by The Braille Authority of North America ©2016 by the Braille Authority of North America All rights reserved. This material may be duplicated but not altered or sold. ISBN: 978-0-9859473-6-1 (Print) ISBN: 978-0-9859473-7-8 (Braille) Printed by the American Printing House for the Blind. Copies may be purchased from: American Printing House for the Blind 1839 Frankfort Avenue Louisville, Kentucky 40206-3148 502-895-2405 • 800-223-1839 www.aph.org [email protected] Catalog Number: 7-09651-01 The mission and purpose of The Braille Authority of North America are to assure literacy for tactile readers through the standardization of braille and/or tactile graphics. BANA promotes and facilitates the use, teaching, and production of braille. It publishes rules, interprets, and renders opinions pertaining to braille in all existing codes. It deals with codes now in existence or to be developed in the future, in collaboration with other countries using English braille. In exercising its function and authority, BANA considers the effects of its decisions on other existing braille codes and formats, the ease of production by various methods, and acceptability to readers. For more information and resources, visit www.brailleauthority.org. ii BANA Music Technical Committee, 2015 Lawrence R. Smith, Chairman Karin Auckenthaler Gilbert Busch Karen Gearreald Dan Geminder Beverly McKenney Harvey Miller Tom Ridgeway Other Contributors Christina Davidson, BANA Music Technical Committee Consultant Richard Taesch, BANA Music Technical Committee Consultant Roger Firman, International Consultant Ruth Rozen, BANA Board Liaison iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .............................................................. -

BASICS of CONDUCTING Bert Appermont

BASICS OF CONDUCTING Bert Appermont 1) Movement - Body and shoulders relaxed - Small opening between the legs - Swinging with the right arm => pulse (like a clock) - Elbow stays almost motionless 2) Meters 2/4 3/4 4/4 3) Downbeat and upbeat 4) Tempo Changes Look for the relation between the two tempo’s 5) Fermata 1. Conduct with stop 2. Conduct with caesura 3. Conduct fermata followed by a rest (without and with tempo change) 6) Ternary Meters - The curves are similar than (2) - The swing movements are bigger (always with pulsation) - Practice 6/8, 9/8 and 12/8 7) Conducting musical character a. Legato: use a more indirect and “wider” curve b. Staccato / leggiero: use the wrist and the top of the baguette), small movement c. Marcato => give an accent by making the pulsation more active => use the elbows (width) to create space in the sound 8) Conducting dynamics f => big gesture p => small gesture mf => normal gesture fp => give an accentuation and suddenly pull back => gesture gradually becomes bigger => gesture gradually becomes smaller 9) Irregular meters 5/8 7/8 + 8/8 10/8 + 11/8 10) Meter changes Exercises: Conduct the following meters 1. 3/4 + 2/4 and 4/4 + 3/4 2. 6/8 + 3/4 and 6/8 + 2/4 3. 9/8 + 3/4 and 9/8 + 2/4 4. 9/8 + 3/4 and 9/8 + 2/4 5. 7/8 (2+2+3) + 5/8 (3+2) and 7/8 (2+2+3) + 6/8 6. 2/8 + 3/8 + 4/8 + 5/8 + 6/8 + 7/8 + 8/8 + 9/8 + 10/8 + 11/8 + 12/8 (and backwards) 11) Using the left hand - to indicate the start of one instrument or instrumental group - to indicate a musical idea: conduct a crescendo or diminuendo; conduct the phrase; point out an accentuation; Exercise 1: conduct 4/4 in the R.H., give a starting signal with the right hand on the 4 different beats Exercise 2: conduct 4/4 in the R.H., conduct one bar crescendo and one bar dim. -

Automatic Handwritten Mensural Notation Interpreter: from Manuscript to Midi Performance

AUTOMATIC HANDWRITTEN MENSURAL NOTATION INTERPRETER: FROM MANUSCRIPT TO MIDI PERFORMANCE ? ? Yu-Hui Huang⇧ , Xuanli Chen⇧ , Serafina Beck†, David Burn†, and Luc Van Gool⇧⌥ ⇧ESAT-PSI, iMinds, KU Leuven †Department of Musicology, KU Leuven ⌥D-ITET, ETH Zurich¨ yu-hui.huang, xuanli.chen, luc.vangool @esat.kuleuven.be, serafina.beck, david.burn @art.kuleuven.be { } { } ?equal contribution ABSTRACT This paper presents a novel automatic recognition frame- work for hand-written mensural music. It takes a scanned manuscript as input and yields as output modern music scores. Compared to the previous mensural Optical Music Recognition (OMR) systems, ours shows not only promis- ing performance in music recognition, but also works as a complete pipeline which integrates both recognition and transcription. There are three main parts in this pipeline: i) region-of- interest detection, ii) music symbol detection and classifi- cation, and iii) transcription to modern music. In addition to the output in modern notation, our system can gener- ate a MIDI file as well. It provides an easy platform for the musicologists to analyze old manuscripts. Moreover, it renders these valuable cultural heritage resources avail- able to non-specialists as well, as they can now access such ancient music in a better understandable form. 1. INTRODUCTION Figure 1: The overview of our framework. (a) Original image after ROI selection. (b) After preprocessing. (c) Cultural heritage has become an important issue nowadays. Symbol segmentation. (d) Transcription results. In the recent decades, old manuscripts and books have been digitalized around the world. As more and more libraries are carrying out digitalization projects, the number of manu- addition to the semantic characteristic, OMR has the addi- scripts increases exponentially every day.