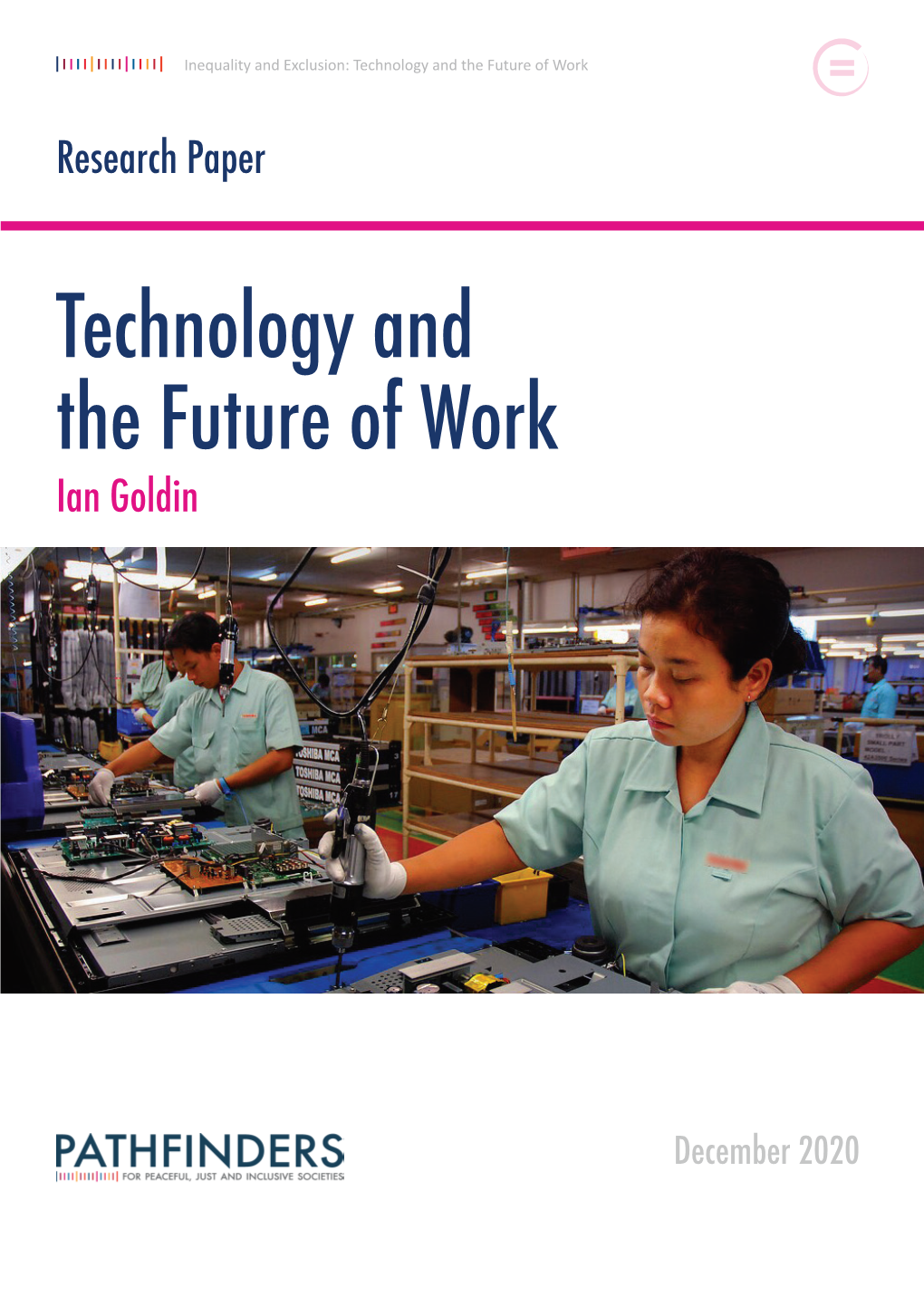

Technology and the Future of Work

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Covid-19 Changed Community Life in the UK

How Covid-19 changed community CONCLUSION + RECOMMENDATION WEEK 01 + 02: 23RD MARCH OVEWIVEW + KEY INSIGHTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS WEEK 04: 13TH APRIL WEEK 05: 20TH APRIL WEEK 06: 27TH APRIL WEEK 03: 6TH APRIL WEEK 08: 11TH MAY WEEK 09: 18TH MAY WEEK 10: 25TH MAY WEEK 12: 8TH JUNE WEEK 11: 1ST JUNE life in the UK WEEK 07: 4TH MAY A week by week archive of life during a pandemic. Understanding the impact on people and communities. 01/2 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 The Young Foundation’s mission is to develop better connected and stronger communities across the UK. As an UKRI accredited research organisation, social CONCLUSION + RECOMMENDATION investor and community practitioner, we offer expert WEEK 01 + 02: 23RD MARCH OVERVIEW + KEY INSIGHTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS WEEK 04: 13TH APRIL WEEK 05: 20TH APRIL WEEK 06: 27TH APRIL WEEK 03: 6TH APRIL WEEK 08: 11TH MAY WEEK 09: 18TH MAY WEEK 10: 25TH MAY WEEK 12: 8TH JUNE WEEK 11: 1ST JUNE advice, training and deliver support to: WEEK 07: 4TH MAY Understand Communities Researching in and with communities to increase your understanding of community life today Involve Communities Offering different methods and approaches to involving communities and growing their capacity to own and lead change Innovate with Communities Providing tools and resources to support innovation to tackle the issues people and communities care about For more information visit us at: youngfoundation.org Overview 01/2 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 Introduction About this document Covid-19 has radically changed the way we go about our day-to-day lives. -

A Leader's Guide: Communicating with Teams, Stakeholders, and Communities During COVID-19 Exhibit 1 of 1

Organization Practice A leader’s guide: Communicating with teams, stakeholders, and communities during COVID-19 COVID-19’s speed and scale breed uncertainty and emotional disruption. How organizations communicate about it can create clarity, build resilience, and catalyze positive change. by Ana Mendy, Mary Lass Stewart, and Kate VanAkin © Ewg3D/Getty Images April 2020 Crises come in different intensities. As a “land- communicators, those whose words and actions scape scale” event,1 the coronavirus has created comfort in the present, restore faith in the long great uncertainty, elevated stress and anxiety, and term, and are remembered long after the crisis has prompted tunnel vision, in which people focus only been quelled. on the present rather than toward the future. During such a crisis, when information is unavailable or So we counsel this: pause, take a breath. The good inconsistent, and when people feel unsure about news is that the fundamental tools of effective what they know (or anyone knows), behavioral communication still work. Define and point to science points to an increased human desire for long-term goals, listen to and understand your transparency, guidance, and making sense out of stakeholders, and create openings for dialogue. Be what has happened. proactive. But don’t stop there. In this crisis leaders can draw on a wealth of research, precedent, and At such times, a leader’s words and actions can experience to build organizational resilience through help keep people safe, help them adjust and an extended period of uncertainty, and even turn a cope emotionally, and finally, help them put their crisis into a catalyst for positive change. -

The Time the Children Didn't Go to School

THE TIME THE CHILDREN DIDN’T GO TO SCHOOL ANNABELLE HAYES FOREWORD ......................................................... 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .................................. 4 APRIL 2020 ............................................................ 5 MAY, 2020 ............................................................ 33 JUNE, 2020 .......................................................... 63 JULY, 2020 ......................................................... 102 AUGUST, 2020 .................................................... 110 SEPTEMBER, 2020 ............................................ 114 OCTOBER, 2020 ............................................... 129 NOVEMBER, 2020 ........................................... 152 DECEMBER, 2020 ............................................ 166 JANUARY, 2021 ................................................. 176 FEBRUARY, 2021 .............................................. 202 MARCH, 2021 .................................................... 223 AFTERWORD ................................................... 230 2 FOREWORD In March 2020, schools, nurseries and colleges in the United Kingdom were shut down in response to the ongoing coronavirus pandemic. By 20 March, all schools in the UK had closed to all children except those of key workers and children considered vulnerable. After a month of numbness at having all the children home, I started these diaries to document the unprecedented time when the children didn’t go to school. When the world stopped, the children didn’t – this records their -

The Path to the Next Normal

The path to the next normal Leading with resolve through the coronavirus pandemic May 2020 Cover image: © Cultura RF/Getty Images Copyright © 2020 McKinsey & Company. All rights reserved. This publication is not intended to be used as the basis for trading in the shares of any company or for undertaking any other complex or significant financial transaction without consulting appropriate professional advisers. No part of this publication may be copied or redistributed in any form without the prior written consent of McKinsey & Company. The path to the next normal Leading with resolve through the coronavirus pandemic May 2020 Introduction On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization formally declared COVID-19 a pandemic, underscoring the precipitous global uncertainty that had plunged lives and livelihoods into a still-unfolding crisis. Just two months later, daily reports of outbreaks—and of waxing and waning infection and mortality rates— continue to heighten anxiety, stir grief, and cast into question the contours of our collective social and economic future. Never in modern history have countries had to ask citizens around the world to stay home, curb travel, and maintain physical distance to preserve the health of families, colleagues, neighbors, and friends. And never have we seen job loss spike so fast, nor the threat of economic distress loom so large. In this unprecedented reality, we are also witnessing the beginnings of a dramatic restructuring of the social and economic order—the emergence of a new era that we view as the “next normal.” Dialogue and debate have only just begun on the shape this next normal will take. -

Covid-19 Staff Testing Update

Dear Provider Today’s Bulletin contains some important information in respect of Covid-19 testing for staff and residents within Care Homes and Hospitals together with details of the Satellite Testing Centre in Keighley. The Bradford Care Association (BCA) had a successful virtual meeting this week with further weekly meetings planned, please try to join these if you are able to. You do not need to be a member of the BCA to participate. Some useful discounts have been announced by the Taxi firm Uber along with other staff support initiatives from several organisations in the district. Don’t forget, from next week all attachments linked to each Bulletin will be available in the new Provider Zone. To access previous Bulletins and attachments, please visit; https://bradford.connecttosupport.org/provider-zone/ It goes without saying; tonight we will all be showing our gratitude for you and your staff at 8pm ‘Clap for Our Carers’. The Commissioning Team COVID-19 STAFF TESTING UPDATE We are aware of the Government’s announcement to make available Covid-19 testing for staff and residents within Care Homes and Hospitals regardless of whether they have any symptoms of the virus. We are currently seeking further guidance on this area via Public Health England and will update this guidance and notify you as soon as soon as possible. In the meantime if you have staff who are isolating due to themselves or a household member having symptoms in the last 1-4 days please continue to process these in line with the guidance issued. If you would like to discuss the content of the guidance note or the process detailed within please contact Jacqui Buckley via email [email protected] BRADFORD DISTRICT AND CRAVEN MARLEY SATELLITE COMMUNITY DRIVE-THROUGH SELF SWABBING CENTRE Please find attached a refreshed (version 7) Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) for Marley Satellite Testing Centre at Keighley. -

Onthefrontline

★ Paul Flynn ★ Seán Moncrieff ★ Roe McDermott ★ 7-day TV &Radio Saturday, April 25, 2020 MES TI SH IRI MATHE GAZINE On the front line Aday inside St Vincent’s Hospital Ticket INSIDE nthe last few weeks, the peopleof rear-viewmirror, there was nothing samey Ireland could feasibly be brokeninto or oppressivelyboring or pedestrian about Inside two factions:the haves and the suburban Dublinatall. Come to think of it, have-nots.Nope, nothing to do with the whys and wherefores of the estate I Ichildren, or holiday homes, or even grew up on were absolutely bewitching.As employment.Instead, I’m talking gardens. kids, we’d duck in and out of each other’s How I’ve enviedmysocialmediafriends houses: ahuge,boisterous,fluid tribe. with their lush, landscaped gardens, or Friends would stay for dinner if there were COLUMNISTS their functionalpatio furniture, or even enough Findus Crispy Pancakes to go 4 SeánMoncrieff their small paddling pools.AnInstagram round.Sometimes –and Idon’tknow how 6 Ross photo of someone enjoying sundownersin or why we ever did this –myfriends and I O’Carroll-Kelly their own back gardenisenough to tip me would swap bedrooms for the night,sothat 17 RoeMcDermott over the edge. Honestly, Icould never have they would be sleeping in my house and Iin 20 LauraKennedy foreseen ascenario in whichI’d look at theirs. Perhaps we fancied ourselvesas someone’smodest back garden and feel characters in our own high-concept, COVERSTORY genuine envy (and, as an interesting body-swap story.Yet no one’s parents 8 chaser, guilt for worrying aboutgardens seemed to mind. -

The COVID-19 Wicked Problem in Public Health Ethics: Conflicting

COMMENT https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00839-1 OPEN The COVID-19 wicked problem in public health ethics: conflicting evidence, or incommensurable values? ✉ Federica Angeli 1 , Silvia Camporesi 2 & Giorgia Dal Fabbro3 While the world was facing a rapidly progressing COVID-19 second wave, a policy paradox emerged. On the one side, much more was known by Autumn 1234567890():,; 2020 about the mechanisms underpinning the spread and lethality of Sars-CoV- 2. On the other side, how such knowledge should be translated by policymakers into containment measures appeared to be much more controversial and debated than during the first wave in Spring. Value-laden, conflicting views in the scientific community emerged about both problem definition and subsequent solutions surrounding the epidemiological emergency, which underlined that the COVID-19 global crisis had evolved towards a full-fledged policy “wicked pro- blem”. With the aim to make sense of the seemingly paradoxical scientific dis- agreement around COVID-19 public health policies, we offer an ethical analysis of the scientific views encapsulated in the Great Barrington Declaration and of the John Snow Memorandum, two scientific petitions that appeared in October 2020. We show that how evidence is interpreted and translated into polar opposite advice with respect to COVID-19 containment policies depends on a different ethical compass that leads to different prioritization decisions of ethical values and societal goals. We then highlight the need for a situated approach to public health policy, which recognizes that policies are necessarily value-laden, and need to be sensitive to context-specific and historic socio-cultural and socio- economic nuances. -

PLEA for PPE AS DOCTORS GO to WAR to SAVE LIVES Only Hour As ‘Absolutely Disgusting’

FREE ISSUE 33 . APRIL 2020 hitehorse Manor Junior School players give to charity Wlit up in blue as a ‘thank you’ to the great staff of the NHS’. CLAP FOR OUR CARERS rystal Palace players have got together to donate an undisclosed Theheard first clapping, week saw banging polite pots applause. and sum of money to help Age UK Croydon Onpans, the car second horns Thursday and dogs at barking 8pm, we their through this crisis. CThe Premier League club confirmed appreciation. Some residents also that: “It was a joint donation made by all displayed blue lights in recognition of the players’ but they wanted to keep the NHSworkers staff. and bin collectors were among amount private. Delivery drivers, supermarket staff, care Age UK Croydon said: “We are very grateful to the players for donating to those honoured. Emergency and NHS us – we’re going to be using the funds to workers also joined in the applause support the key services we’re operating COVID-19including firefighters HOUSING in Croydon. CRISIS AS NORTH OF THE BOROUGH WORST HIT BY VIRUS right now.” he council is desperately trying HUGE AID EFFORT Tto find accommodation to house huge humanitarian aid effort families in cramped accommodation A has been launched to help the rallying together to support each other, borough’s elderly and vulnerable. who are unable to self isolate from getting to know neighbours delivering elderly and vulnerable relatives. In just over two weeks over 3,000 food which had been “wonderful”. Croydon residents have joined Deputy Leader Cllr Alison Butler said: Croydon Covid-19 Mutual Aid (CCMA) “We have escalated work on voids and to help serve their neighbours and Options being looked at include other council assets required for Covid the most vulnerable through the hotels, private buildings and the newly 19for duties.accommodation At the moment for those and who probably coronavirus crisis. -

Sixty Seconds on . . . the Clap

BMJ 2020;369:m2183 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2183 (Published 1 June 2020) Page 1 of 1 News BMJ: first published as 10.1136/bmj.m2183 on 1 June 2020. Downloaded from NEWS Sixty seconds on . the clap Abi Rimmer The BMJ Gonorrhoea? better, improve their conditions, fund the NHS. Clapping is an empty gesture.” Ah ha, got you! No, I’m talking about the weekly “clap for our carers” that has seen the public standing on their doorsteps each Thursday for the past 10 weeks, clapping in support of NHS Any other matters taken in hand? and frontline workers. Yes, some doctors have commented that there might be a more appropriate way to remember those healthcare workers who had How did it start? lost their lives to covid-19. Consultant psychiatrist JS Bamrah tweeted, “I’d rather have a minute’s silence than clap. Painful Dutch Londoner Annemarie Plas is the woman credited with to see so many friends and colleagues ravaged by the virus.” launching the initiative. She was inspired by people in other countries showing their gratitude for key workers through mass applause.1 Dare I mention the other “C” word? Let’s just say that the end of the clapping may well be timed. http://www.bmj.com/ And there’s a weekly encore? As intensive care medic Chris Danbury, referring to government support for Dominic Cummings, put it on Twitter,6 “Utterly There has been. The first clap took place on 26 March and at 8 appalling hypocrisy. Do you think that clapping for my pm every Thursday since then people have been clapping. -

Medical Humanities Journal Article

Critical Metadata Analysis and Data Visualization of United States, United Kingdom, and Ireland World Leaders Twitter Responses to COVID-19 Esther Ruth Kentish ( [email protected] ) University of Oxford https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6476-4964 Research Article Keywords: COVID-19, Twitter, critical metadata analysis Posted Date: May 17th, 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-529064/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License INTRODUCTION Twitter can be utilized as a tool in Medical Education because it may serve as a learning tool and a mode of sharing critical medical updates and scientific communication. Medical Humanities scholars may utilize the social media site to situate knowledge on the novel COVID-19, also known as coronavirus. Presently, several world leaders utilize Twitter.com to communicate scientific findings as well as their own views of COVID-19. Brandt and Botelho (2020) argue that COVID-19 can be described as the "perfect storm" because of its unpredictability. COVID-19 affected the entire world from its onset in December 2019. COVID-19 has marked itself as an unpredictable virus and was initially difficult to track. Brandt and Botelho (2020) argue that COVID-19 is overly described as unpredictable because of the "rare combination of adverse meteorological factors". Whilst COVID-19 itself as a pandemic is unpredictable, some of the ways that the government is handling the situation was also very unclear. Thus, this research was pursued to follow the government's stance on the development of COVID-19 and the policies and procedures that they would follow and employ to assert control over the situation. -

Psychological Distress and the Perceived Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on UK Dentists During a National Lockdown

RESEARCH Psychological distress and the perceived impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on UK dentists during a national lockdown Victoria Collin,*1 Ellena O’Selmo1 and Penny Whitehead1 Key points Identifes stressors for dentists and their Outlines the variety of circumstances and working Shows that overall psychological distress was perceived impact, including novel stressors environments dentists were working in during reduced during lockdown for dentists, attributed introduced during the lockdown period. lockdown. to the stressors of day-to-day clinical dentistry being alleviated for many. Abstract Introduction Dentists are known to function under stressful conditions. It is important to monitor, examine and understand the psychological efects the unprecedented challenge of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has had. Aims To compare levels of psychological distress in UK dentists, before and during the pandemic, to determine if this was afected. Materials and methods An online survey collected demographic data, levels of psychological distress (GP-CORE) and experiences from UK dentists during the ‘ational lockdown’ period of the pandemic. Statistical and thematic analyses were performed and data compared with previous research. Results Psychological distress was lower in UK dentists during the national lockdown period when compared to previous research using the same measure. GDPs, those in England and those with mixed commitment reported the highest levels of psychological distress. Most dentists had been afected by the pandemic. Some who were remotely working during this time valued the time away from the profession, relishing the absence of regulatory and contractual stressors, and used lockdown as an opportunity to re-evaluate their lives and careers. -

Applause for Carers Questions

30th March 2020 Daily News Special Report UK News Why did people clap? • On 26th March, at 8 p.m., people Applause applauded NHS workers. for Carers • People did this to say thank you. Illustraton: People clapping carers. People Unite to Thank NHS Workers On Thursday, people around the UK went to A group called Clap for Our Carers tried their doorsteps or windows to clap workers to get as many people as possible to join in. in the NHS. They said that NHS workers needed “to know They wanted to thank healthcare workers that we are grateful.” who are helping those in need. Healthcare Clapping carers hasn’t just happened in the workers can include doctors, nurses, carers UK. People in other countries are doing it too. and volunteers. In France, the Netherlands and Spain, people People didn’t just clap to show their have clapped for healthcare workers. thanks. Some people let off fireworks! Others even banged pots or waved flags. Some Glossary people made their own banners. A lot of people wrote messages of thanks NHS National Health Service, on social media. The royal family shared responsible for UK images of themselves clapping carers. healthcare. Prince William and Catherine, Duchess of healthcare People who work to improve Cambridge, wrote a thank-you message to people’s health, such “all NHS staff working tirelessly to help.” as doctors. Famous buildings were lit up in blue, volunteers People who work without the colour of the NHS, including Wembley being paid. Stadium and the London Eye. On social media, the NHS thanked people tirelessly To work really hard to help for clapping.