Man with a Movie Camera (SU 1929) Under the Lens of Cinemetrics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rosamunde Pilcher and Englishness

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OTHES Diplomarbeit Titel der Diplomarbeit Rosamunde Pilcher and Englishness Verfasserin Helena Schuhmacher Angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Mag. Phil.) Wien, im Dezember 2010 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt A 190 344 353 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt UF Englisch (und UF Spanisch) Betreuerin ao. Univ. Prof. Dr. Monika Seidl I would like to seize the opportunity to express my warmest thanks to all those people who have encouraged me or lent me an ear in the course of my studies. I would like to thank my parents who have always let me decide on my own and who have made it possible for me to take up and complete my university studies. Furthermore, my warmest thanks are reserved for Prof. Seidl, without whom I would have not arrived at the idea of writing the current thesis. Moreover, I would like to thank her for all her words of advice and encouragement. Table of Contents 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1 2. Theoretical Framework ........................................................................................... 3 2. 1. Nation as an imagined community ...................................................................... 3 2. 2. Collective memory and nostalgia in the heritage film ..................................... 8 2. 3. Englishness ............................................................................................................18 -

Film Film Film Film

Annette Michelson’s contribution to art and film criticism over the last three decades has been un- paralleled. This volume honors Michelson’s unique C AMERA OBSCURA, CAMERA LUCIDA ALLEN AND TURVEY [EDS.] LUCIDA CAMERA OBSCURA, AMERA legacy with original essays by some of the many film FILM FILM scholars influenced by her work. Some continue her efforts to develop historical and theoretical frame- CULTURE CULTURE works for understanding modernist art, while others IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION practice her form of interdisciplinary scholarship in relation to avant-garde and modernist film. The intro- duction investigates and evaluates Michelson’s work itself. All in some way pay homage to her extraordi- nary contribution and demonstrate its continued cen- trality to the field of art and film criticism. Richard Allen is Associ- ate Professor of Cinema Studies at New York Uni- versity. Malcolm Turvey teaches Film History at Sarah Lawrence College. They recently collaborated in editing Wittgenstein, Theory and the Arts (Lon- don: Routledge, 2001). CAMERA OBSCURA CAMERA LUCIDA ISBN 90-5356-494-2 Essays in Honor of Annette Michelson EDITED BY RICHARD ALLEN 9 789053 564943 MALCOLM TURVEY Amsterdam University Press Amsterdam University Press WWW.AUP.NL Camera Obscura, Camera Lucida Camera Obscura, Camera Lucida: Essays in Honor of Annette Michelson Edited by Richard Allen and Malcolm Turvey Amsterdam University Press Front cover illustration: 2001: A Space Odyssey. Courtesy of Photofest Cover design: Kok Korpershoek, Amsterdam Lay-out: japes, Amsterdam isbn 90 5356 494 2 (paperback) nur 652 © Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam, 2003 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, me- chanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permis- sion of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. -

Dziga Vertov — Boris Kaufman — Jean Vigo E

2020 ВЕСТНИК САНКТ-ПЕТЕРБУРГСКОГО УНИВЕРСИТЕТА Т. 10. Вып. 4 ИСКУССТВОВЕДЕНИЕ КИНО UDC 791.2 Dziga Vertov — Boris Kaufman — Jean Vigo E. A. Artemeva Mari State University, 1, Lenina pl., Yoshkar-Ola, 424000, Russian Federation For citation: Artemeva, Ekaterina. “Dziga Vertov — Boris Kaufman — Jean Vigo”. Vestnik of Saint Petersburg University. Arts 10, no. 4 (2020): 560–570. https://doi.org/10.21638/spbu15.2020.402 The article is an attempt to discuss Dziga Vertov’s influence on French filmmakers, in -par ticular on Jean Vigo. This influence may have resulted from Vertov’s younger brother, Boris Kaufman, who worked in France in the 1920s — 1930s and was the cinematographer for all of Vigo’s films. This brother-brother relationship contributed to an important circulation of avant-garde ideas, cutting-edge cinematic techniques, and material objects across Europe. The brothers were in touch primarily by correspondence. According to Boris Kaufman, dur- ing his early career in France, he received instructions from his more experienced brothers, Dziga Vertov and Mikhail Kaufman, who remained in the Soviet Union. In addition, Vertov intended to make his younger brother become a French kinok. Also, À propos de Nice, Vigo’s and Kaufman’s first and most “vertovian” film, was shot with the movable hand camera Kina- mo sent by Vertov to his brother. As a result, this French “symphony of a Metropolis” as well as other films by Vigo may contain references to Dziga Vertov’s and Mikhail Kaufman’sThe Man with a Movie Camera based on framing and editing. In this perspective, the research deals with transnational film circulations appealing to the example of the impact of Russian avant-garde cinema on Jean Vigo’s films. -

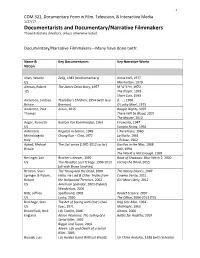

Documentarists and Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers Those Listed Are Directors, Unless Otherwise Noted

1 COM 321, Documentary Form in Film, Television, & Interactive Media 1/27/17 Documentarists and Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers Those listed are directors, unless otherwise noted. Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers—Many have done both: Name & Key Documentaries Key Narrative Works Nation Allen, Woody Zelig, 1983 (mockumentary) Annie Hall, 1977 US Manhattan, 1979 Altman, Robert The James Dean Story, 1957 M*A*S*H, 1970 US The Player, 1992 Short Cuts, 1993 Anderson, Lindsay Thursday’s Children, 1954 (with Guy if. , 1968 Britain Brenton) O Lucky Man!, 1973 Anderson, Paul Junun, 2015 Boogie Nights, 1997 Thomas There Will be Blood, 2007 The Master, 2012 Anger, Kenneth Kustom Kar Kommandos, 1963 Fireworks, 1947 US Scorpio Rising, 1964 Antonioni, Ragazze in bianco, 1949 L’Avventura, 1960 Michelangelo Chung Kuo – Cina, 1972 La Notte, 1961 Italy L'Eclisse, 1962 Apted, Michael The Up! series (1970‐2012 so far) Gorillas in the Mist, 1988 Britain Nell, 1994 The World is Not Enough, 1999 Berlinger, Joe Brother’s Keeper, 1992 Book of Shadows: Blair Witch 2, 2000 US The Paradise Lost Trilogy, 1996-2011 Facing the Wind, 2015 (all with Bruce Sinofsky) Berman, Shari The Young and the Dead, 2000 The Nanny Diaries, 2007 Springer & Pulcini, Hello, He Lied & Other Truths from Cinema Verite, 2011 Robert the Hollywood Trenches, 2002 Girl Most Likely, 2012 US American Splendor, 2003 (hybrid) Wanderlust, 2006 Blitz, Jeffrey Spellbound, 2002 Rocket Science, 2007 US Lucky, 2010 The Office, 2006-2013 (TV) Brakhage, Stan The Act of Seeing with One’s Own Dog Star Man, -

Film Studies A-Level Induction Work to Prepare You for September 2021

Film Studies A-Level Induction work to prepare you for September 2021 Email Miss Potts or Mr Howse if you have any questions – [email protected] or [email protected] Component 1: Varieties of film and filmmaking - Exam – 2 ½ Component 2: Global filmmaking perspectives - Exam – 2 ½ hours – 35% hours – 35% Section A: Hollywood 1930-1990 (comparative study) Section A: Global film (two-film study) Group 1: Classical Hollywood 1930- Group 2: New Hollywood (1961- Group 1: European Film Group 2: Outside Europe 1960) 1990) - Life is Beautiful (Benigni, Italy, 1997, - Dil Se (Ratnam, India, 1998, 12) - Casablanca (Curtiz, 1942, U) - Bonnie and Clyde (Penn, 1967, 15) PG) - City of God (Meirelles, Brazil, 2002) - The Lady from Shanghai (Welles, - OFOTCN (Forman, 1975, 15) - Pan’s Labyrinth (Del Toro, Spain, 2006, - House of Flying Daggers (Zhang, China, 1947, PG) - Apocalypse Now (Coppola, 1979, 15) 2004, 15) - Johnny Guitar (Ray, 1954, PG) 15) - Diving Bell (Schnabel, France 2007, 12) - Timbuktu (Sissako, Mauritania, 2014, - Vertigo (Hitchcock, 1958, PG) - Blade Runner (Scott, 1982, 15) - Ida (Pawlikowski, Poland, 2013, 15) 12A) - Some Like It Hot (Wilder, 1959, 12) - Do The Right Thing (Lee, 1989, 15) - Mustang (Erguven, Turkey, 2015, 15) - Wild Tales (Szifron, Argentina, 2014, 15) - Victoria (Schipper, Germany, 2015, 15) - Taxi Tehran (Panahi, Iran, 2015, 12) Section B: American film since 2005 (two-film study) Section B: Documentary film Section C: Film movements – Silent - Sisters in Law (Ayisi, Cameroon, 20015, Group -

Documentary Movies

Libraries DOCUMENTARY MOVIES The Media and Reserve Library, located in the lower level of the west wing, has over 9,000 videotapes, DVDs and audiobooks covering a multitude of subjects. For more information on these titles, consult the Libraries' online catalog. 10 Days that Unexpectedly Changed America DVD-2043 56 Up DVD-8322 180 DVD-3999 60's DVD-0410 1-800-India: Importing a White-Collar Economy DVD-3263 7 Up/7 Plus Seven DVD-1056 1930s (Discs 1-3) DVD-5348 Discs 1 70 Acres in Chicago: Cabrini Green DVD-8778 1930s (Discs 4-5) DVD-5348 Discs 4 70 Acres in Chicago: Cabrini Green c.2 DVD-8778 c.2 1964 DVD-7724 9/11 c.2 DVD-0056 c.2 1968 with Tom Brokaw DVD-5235 9500 Liberty DVD-8572 1983 Riegelman's Closing/2008 Update DVD-7715 Abandoned: The Betrayal of America's Immigrants DVD-5835 20 Years Old in the Middle East DVD-6111 Abolitionists DVD-7362 DVD-4941 Aboriginal Architecture: Living Architecture DVD-3261 21 Up DVD-1061 Abraham and Mary Lincoln: A House Divided DVD-0001 21 Up South Africa DVD-3691 Absent from the Academy DVD-8351 24 City DVD-9072 Absolutely Positive DVD-8796 24 Hours 24 Million Meals: Feeding New York DVD-8157 Absolutely Positive c.2 DVD-8796 c.2 28 Up DVD-1066 Accidental Hero: Room 408 DVD-5980 3 Times Divorced DVD-5100 Act of Killing DVD-4434 30 Days Season 3 DVD-3708 Addicted to Plastic DVD-8168 35 Up DVD-1072 Addiction DVD-2884 4 Little Girls DVD-0051 Address DVD-8002 42 Up DVD-1079 Adonis Factor DVD-2607 49 Up DVD-1913 Adventure of English DVD-5957 500 Nations DVD-0778 Advertising and the End of the World DVD-1460 -

Films from the Archives of the Museum of Modern Art and the George Eastman House

'il The Museum of Modem Art FOR ™IATE RRLEASF yvest 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Tel. 956-6100 Cable: Modernart KINO EYE OF THE 20s FEATURES FILM MASTERPIECES Films from the Archives of The Museum of Modern Art and The George Eastman House The Museum of Modern Art, in collaboration with the George Eastman House in Roches ter, will present several film masterpieces as part of its program "Kino Eye of the 20s," starting July 23 with Ilya Trauberg's "China Express." The program, scheduled through August 26, will also include such film classics as Carl Dreyer's "The Passion of Joan of Arc;" Pudovkin's "Mother;" Erich von Stroheim's "Greed;" F.W. Murnau's "The Last Laugh;" Eisenstein's "Potemkin;" and "The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari," one of the most controversial films of its time. Thirty-seven pictures were selected by Beaumont Newhall, Director of the George Eastman House, who is responsible for organizing the current photographic exhibition, "Photo Eye of the 20s," to which "Kino Eye of the 20s" is a companion program. Mr. Newhall will appear at the Thursday evening performance, July 30 at 8 p.m., fjhen he will introduce the Murnau film "Sunrise" and discuss the series. A strong kinship between photography and film existed in this decade, when the film found its syntax and structure, according to Mr. NeT;hall. "In a quarter of a century the movies had grown from a vaudeville novelty to a distinct and po';erful art form." The decade saw the production of some of the greatest films ever made. -

Illustrations

Illustrations 1. Long shot of Flora, The Birth of a Nation 10 2. Image of a fence in the frame showing Gus, a black man about to pursue a young white woman, The Birth of a Nation 12 3. Close-up of Gus, The Birth of a Nation 14 4. Flora through Gus’s eyes, The Birth of a Nation 15 5. An extreme long shot of the people running down the Odessa Steps, The Battleship Potemkin 29 6. A big close-up of a pair of legs, The Battleship Potemkin 29 7. The purposeful, organized movement of the soldiers, The Battleship Potemkin 30 8. The chaotic, disorganized movements of the victims, The Battleship Potemkin 30 9. A boy’s body creates a graphic conflict with the line of the steps, The Battleship Potemkin 31 10. A woman carrying a wounded child ascends the steps, her body casting a shadow, The Battleship Potemkin 35 11. Soldiers’ bodies cast their shadows on the woman and child, The Battleship Potemkin 35 12. Cesare, shortly before he collapses in exhaustion, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari 38 ix x ILLUSTRATIONS 13. Buildings lean, bend, or rear straight up, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari 39 14. Emil Jannings in a medium close-up from slightly below, The Last Laugh 41 15. Emil Jannings photographed from a high angle, The Last Laugh 42 16. From the doorman’s point of view, the neighbor woman’s face grotesquely elongated, The Last Laugh 43 17. Images of the hotel dining room merge with images of the doorman’s tenement neighborhood, The Last Laugh 46 18. -

The Age of Distraction: Photography and Film Quentin Bajac

The Age of Distraction: Photography and Film quentin bajac Cult of Distraction In the immediate post–World War I period, distraction was perceived as one of the fundamental elements of the modern condition.1 These years — described as folles in French, roaring in the United States, and wilden in German2 — were also “distracted” years, in every sense of the term: in the sense of modern man’s new incapacity to focus his attention on the world, as well as a thirst to forget his own condition, to be entertained. In the eyes of then- contemporary observers, the new cinema — with its constant flux of images and then sounds, which seemed in contrast with the old contemplation of the unique and motionless work — offered the best illustration of this in the world of the visual arts (fig. 1). In 1926, in his essay “Kult der Zerstreuung” (Cult of distraction), Siegfried Kracauer made luxurious Berlin movie theaters — sites par excellence of the distraction of the masses — the point of departure and instrument of analysis of German society in the 1920s. In the temples of distraction, he wrote, “the stimulations of the senses suc- ceed each other with such rapidity that there is no room left for even the slightest contemplation to squeeze in between them,”3 a situation he compared to the “increasing amount of illustrations in the daily press and in periodical publications.”4 The following year, in 1927, he would pursue this idea in his article on photography,5 deploring the “bliz- zard” of images in the illustrated press that had come to distract the masses and divert the perception of real facts. -

101 Films for Filmmakers

101 (OR SO) FILMS FOR FILMMAKERS The purpose of this list is not to create an exhaustive list of every important film ever made or filmmaker who ever lived. That task would be impossible. The purpose is to create a succinct list of films and filmmakers that have had a major impact on filmmaking. A second purpose is to help contextualize films and filmmakers within the various film movements with which they are associated. The list is organized chronologically, with important film movements (e.g. Italian Neorealism, The French New Wave) inserted at the appropriate time. AFI (American Film Institute) Top 100 films are in blue (green if they were on the original 1998 list but were removed for the 10th anniversary list). Guidelines: 1. The majority of filmmakers will be represented by a single film (or two), often their first or first significant one. This does not mean that they made no other worthy films; rather the films listed tend to be monumental films that helped define a genre or period. For example, Arthur Penn made numerous notable films, but his 1967 Bonnie and Clyde ushered in the New Hollywood and changed filmmaking for the next two decades (or more). 2. Some filmmakers do have multiple films listed, but this tends to be reserved for filmmakers who are truly masters of the craft (e.g. Alfred Hitchcock, Stanley Kubrick) or filmmakers whose careers have had a long span (e.g. Luis Buñuel, 1928-1977). A few filmmakers who re-invented themselves later in their careers (e.g. David Cronenberg–his early body horror and later psychological dramas) will have multiple films listed, representing each period of their careers. -

Dziga Vertov, Travel Cinema, and Soviet Patriotism*

Across One Sixth of the World: Dziga Vertov, Travel Cinema, and Soviet Patriotism* OKSANA SARKISOVA The films of Dziga Vertov display a persistent fascination with travel. Movement across vast spaces is perhaps the most recurrent motif in his oeuvre, and the cine-race [kino-probeg]—a genre developed by Vertov’s group of filmmak- ers, the Kinoks 1—stands as an encompassing metaphor for Vertov’s own work. His cinematographic journeys transported viewers to the most remote as well as to the most advanced sites of the Soviet universe, creating a heterogeneous cine-world stretching from the desert to the icy tundra and featuring customs, costumes, and cultural practices unfamiliar to most of his audience. Vertov’s personal travelogue began when he moved from his native Bialystok2 in the ex–Pale of Settlement to Petrograd and later to Moscow, from where, hav- ing embarked on a career in filmmaking, he proceeded to the numerous sites of the Civil War. Recalling his first steps in cinema, Vertov described a complex itin- erary that included Rostov, Chuguev, the Lugansk suburbs, and even the Astrakhan steppes.3 In the early 1920s, when the film distribution network was severely restricted by the Civil War and uneven nationalization, traveling and film- making were inseparable. Along with other filmmakers, he used an improvised * This article is part of my broader research “Envisioned Communities: Representations of Nationalities in Non-Fiction Cinema in Soviet Russia, 1923–1935” (Ph.D. Dissertation, Central European University, 2004). I would like to warmly thank my teachers and friends for sharing their knowledge and enthusiasm throughout this long journey. -

Film and Literary Modernism

Film and Literary Modernism Film and Literary Modernism Edited by Robert P. McParland Film and Literary Modernism, Edited by Robert P. McParland This book first published 2013 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2013 by Robert P. McParland and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-4450-0, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-4450-5 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 I. City Symphony Films A City Symphony: Urban Aesthetics and the Poetics of Modernism on Screen ................................................................................................... 12 Meyrav Koren-Kuik The Experimental Modernism in the City Symphony Film Genre............ 20 Cecilia Mouat Reconsidering Charles Sheeler and Paul Strand’s Manhatta..................... 27 Kristen Oehlrich II. Perspectives To See is to Know: Avant-Garde Film as Modernist Text ........................ 42 William Verrone Tomato’s Another Day: The Improbable Subversion of James Sibley Watson and Melville Webber ..................................................................