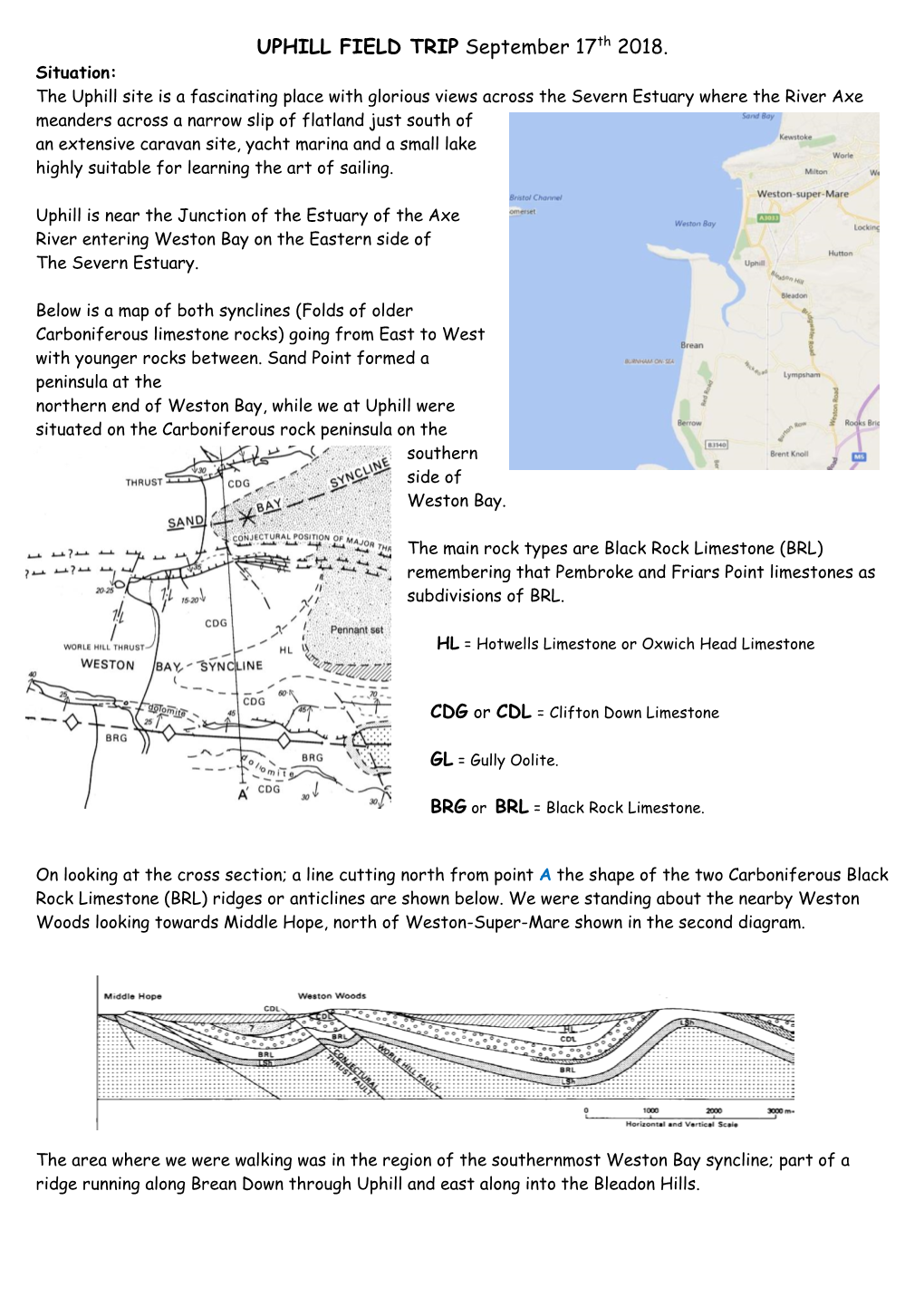

UPHILL FIELD TRIP September 17Th 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Middle Hope to Brean Down

Middle Hope to Brean Down Existing defences and What can be done? probability of flooding Monitoring will continue at Sand Bay As a result of recent improvements to Beach and levels may need raising after defences by the Local Authority (marked in 2040. The beach can provide a high purple on the map), the risk of tidal level of protection up to 2110, with the flooding to most properties at Weston- probability of flooding being 1 in 200 in Super-Mare is 1 in 200 or less in any year. any year. We are currently producing a However the chance of wave disruption beach management plan for Sand Bay. here is 1 in 5 or less in any year. Maintenance and improvements will be Some agricultural areas to the north of carried out on the defences at Weston- Weston-Super-Mare have a 1 in 20 chance Super-Mare and Uphill through working of flooding in any year. with other authorities. The sea wall at Weston-Super-Mare will provide a high At Sand Bay, the sand dunes, salt marsh level of protection up to 2110 but may and beach, as well as the sea wall at the need raising after 2060 to reduce wave north of the bay provide a flood defence. overtopping. We are working with the There is a low risk of significant flooding; Local Authority to create a beach however the moveable nature of sand management plan for Weston Bay. dunes means that the probability of flooding can change in a short space of Landowners can help to maximise the time. -

Mendip Hills AONB Survey

Mendip Hills An Archaeological Survey of the Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty by Peter Ellis ENGLISH HERITAGE Contents List of figures Introduction and Acknowledgements ...................................................1 Project Summary...................................................................................2 Table 1: New sites located during the present survey..................3 Thematic Report Introduction ................................................................................10 Hunting and Gathering...............................................................10 Ritual and Burial ........................................................................12 Settlement...................................................................................18 Farming ......................................................................................28 Mining ........................................................................................32 Communications.........................................................................36 Political Geography....................................................................37 Table 2: Round barrow groups...................................................40 Table 3: Barrow excavations......................................................40 Table 4: Cave sites with Mesolithic and later finds ...................41 A Case Study of the Wills, Waldegrave and Tudway Quilter Estates Introduction ................................................................................42 -

Great Weston Conservation Area

GREAT WESTON CONSERVATION AREA Conservation Area Appraisal and Management Plan AN INTRODUCTION Allies and Morrison September 2018 Urban Practitioners Draft for consultation How to find your way around HOW TO USE THIS 1. 3. 5. DOCUMENT An Introduction Character Area 1: Seafront Character Area 3: Hillside This document introduces the Page 4 Great Weston Conservation Area and what makes it special. The conservation area is divided into four character Introduction and history Introduction and history areas. This document can be read as a comprehensive overview and guide to the Summary of special character Summary of special character single conservation area, but if you would like to learn more Overview of current condition Overview of current condition about each character area, there are individual appraisals Mapping character Mapping character which can be viewed and accessed separately for ease. Changes affecting the area These can be found here: Changes affecting the area THIS DOCUMENT www.n-somerset.gov.uk/ Management proposals Management proposals westonconservation INTERACTIVE 2. 4. 6. This document is intended to be Management guidance Character Area 2: Town Centre read online. You can navigate Character Area 4: Whitecross through it using the interactive links on the contents page and throughout the report. The draft for consultation Challenges Introduction and history Introduction and history sets out the appraisal of the conservation area. Following Summary of special character Summary of special character the consultation, sections Opportunities will be drafted on how the conservation area and each Implementation Overview of current condition Overview of current condition individual character area should be managed. This Mapping character Mapping character contents page shows how these sections will sit in the Appendix Changes affecting the area Changes affecting the area wider document structure (Section 2). -

Uphill Walks 10 Healthy Walks Around and About Uphill Village Third Edition

Uphill Walks 10 Healthy Walks Around and About Uphill Village Third Edition Uphill Walks 1! Health Walks at Uphill Explore the wonderful fauna and flora around Uphill as well as going for a purposeful walk to improve your health. A health walk aims to: • Encourage people, particularly those who undertake little physical activity, to walk on a regular basis within their communities. • Ensure the walk is purposeful and brisk but not too challenging for those who have not exercised recently. • Plan the walk so it is safe, accessible, manageable and enjoyable. Health walks are all about getting inactive people on the first rung of the ladder to a more active lifestyle. So if you enjoy exercise in the fresh air a health walk may be just what you are looking for. Please note that walks 4 to 9 in this book are over three miles and only suitable for those who walk regularly and are used to walking this distance over uneven terrain and up moderate to steep inclines. Uphill Walks 2! Why Walk? Walking can: • Make you feel good • Give you more energy • Reduce stress and help you sleep better • Keep your heart 'strong' and reduce blood pressure • Help to manage your weight Why is walking the perfect activity for health? • Almost everyone can do it • You can do it anywhere and any time • It's a chance to make new friends • It's free and you don't need special equipment • You can start slowly and build up gently To help motivate you to walk more why not take up the step counter loan service. -

Baker, W, Geology of Somerset, Volume 1

GEOLOGY OP SOMERSET. 127 (©rnlngq nf $mmtt BY MR. W. BAKER. ICOME before you as one of the representatives of the natural history department of this society, to offer a few observations on the most striking geological features of our highly interesting field of research,— the beautiful county of Somerset. The course which I have laid out for myself is, to pass from the oldest formation, in the order of geological time, to our rieh alluvial lands, which are now in a state of accumulation ; and to offer a few brief remarks on the features of the principal formations, merely to open the way for future papers of detail, on the numerous interesting por- tions of the province, which we now call our own. More than thirty years ago, a young member of our very oldest geological family, — syenite— was observed at Hestercombe, one of the extended branches of the Quantock-hills, and the fact re- corded in the transactions of the London Geological 128 PAPERS, ETC. Society, by Leonard Horner, Esq. late president of that Society. —This discovery indicates tliat granite may be found in other parts of our western district. The Quantocks, and the hüls farther west, are the transition, or grauwacke, formation, and are of the lowest sedimentary deposits. Few or no organic remains have been found in the grauwacke of Somerset, but some are known in the sarae class of rocks in Devon and Cornwall. In our hüls, however, we have numerous beds of limestone, rieh in madrepores, corals and encrinites. This limestone is much quarried for manure in several places. -

UVS Trustee Profiles 2019

UPHILL VILLAGE SOCIETY TRUSTEE PROFILES STEWART CASTLE - CHAIR Stewart has lived in Uphill Village for over 27 years and has been a member of the village society throughout that time and is currently Chair. During his time with the society he oversaw the introduction of the popular Scarecrow Festival and Village Weekend linking the school and village fetes with the annual duck race and sandcastle festival. He brought the millennium beacon to the village and which now burns every New Year and on other national occasions. In addition he secured substantial Town Council funding for the benefit of the village and which greatly helped in meeting the cost of many enhancement projects. He edits the village magazine and lead the World War 1 memorial project. Throughout his time living in the village Stewart has served on the governing bodies of the Uphill Primary, Westhaven and Broadoak schools. He has three children who all attended the village school as did their mother, uncle, grandfather and great grandfather. His granddaughter now also attends as the fifth generation of the family at the school. BECKY CARDWELL - TREASURER Becky was born and raised in Weston, attending Wyvern Secondary School and Weston Sixth Form College. After successfully completing her A Levels, Becky started an apprenticeship in Accounting and has worked in various finance and accounting roles over the last ten years. Becky currently works as a management accountant for an insurance company. Becky moved to Uphill in 2015 with her husband and they now raise a young family. LEIGH MORRIS – SECRETARY Leigh was born in Weston and has lived in Uphill since 1995. -

Mick Aston's 'Ancient Archaeology in Uphill' Walk

Mick Aston's 'Ancient Archaeology in Uphill' walk Always follow current UK Government guidelines for COVID-19 (www.gov.uk/ coronavirus) when enjoying this walk and check the most up to date advice before setting off. Before his passing in 2013, the late Mick Aston - best known for his 20 year stint as resident academic on Channel 4's Time Team -was an enthusiastic supporter of The Churches Conservation Trust, help in� us promote and plan a series of projects in Somerset in particular at St Andrew's Church, Holcombe. The Old Church of St Nicholas at Uphill, Somerset, was a particular favourite of Mick's and this walk was suggested by him to explore the beauty of the surrounding area. Mick said: "This beautiful walk takes in stunning views of the Severn Estuary/ Bristol Channel -and the contrasting scenery of the mendips and the Somerset Levels. I particularly like the open grassland of the Mendip limestone upland, the rhynes (ditches) and wetlands of the Levels, the tidal mud of the creek with its changing water levels, the boats at Uphill and the distant views from St Nicholas' Church, Uphill." Walk directions Start - Uphill Boatyard, Uphill Wharf, Weston-super-Mare, BS23 4XR Start by the new flood�ate in Uphill, and walk throu�h the boatyard. Beyond the boatyard, bear ri�ht, and follow the path that runs alon�side the 'pill' or inlet which �ives Uphill its name ('place above the pill or creek'), onto the marshes of the Levels. If you wish, you can also take the alternative route of followin� the base of the limestone cliffs to the left of the boatyard - these cliffs must have been the shoreline many thousands of years a�o and caves with si�ns of early prehistoric occupation have been found in them. -

Weston Bay Beach and Dune Management Plan

Weston Bay Beach and Dune Management Plan North Somerset Council December 2013 Final Draft Report 9Y0510 HASKONING UK LTD. RIVERS, DELTAS & COA STS Stratus House Emperor Way Exeter, Devon EX1 3QS United Kingdom +44 1392 447999 Telephone 01392 446148 Fax [email protected] E-mail www.royalhaskoningdhv.com Internet Document title Weston Bay Beach and Dune Management Plan Document short title Weston Beach Management Plan Status Final Draft Report Date December 2013 Project name Weston Bay Beach and Dune Management Plan Project number 9Y0510 Client North Somerset Council Reference 9Y0510/R00001/303395/Exet Drafted by Eddie Crews Checked by Martha Gaches Date/initials check 13 th December 2013 Approved by Martha Gaches th Date/initials approval 13 December 2013 A company of Royal HaskoningDHV SUMMARY This Beach and Dune Management Plan describes an investigation of the contemporary and historic geomorphic change of Weston Bay and the Axe Estuary, North Somerset, and its potential implications for coastal flood risk. The plan provides management options that aim to ensure that the beach and dunes provide effective flood protection into the future. Three main types of coastal flood defence are present within the study area: sea walls in the northern half of the beach, sand dunes in the southern part of the beach and flood embankments lining the Axe Estuary. Historic mapping, survey data and field observations have been used to assess changes in the form of the beach and dunes and to interpret flows of sediment transport. It is found that the beach has historically remained relatively stable with a general movement of sediment from north to south. -

North Somerset Council Liberal Democrat Group Submission to Local Government Boundary Commission for England North Somerset Further Electoral Review 2013

North Somerset Council Liberal Democrat Group Submission to Local Government Boundary Commission for England North Somerset Further Electoral Review 2013 Apportionment of councillors The new council size has been established as 51 councillors. Apportioning this number among the four towns and the rural area (with a few minor modifications as will be explained in our report) gives the following figures: 2018 Seat Rounded Area electorate entitlement to Weston-super-Mare+Kewstoke+Woodside from Hutton 64,390 19.34 19 Portishead 20,946 6.29 6 Clevedon 17,481 5.25 5 Nailsea+Green Pastures from Wraxall 13,791 4.14 4 Remaining rural area 53,163 15.97 16 Total 169,771 51 50 With rounding the numbers apportioned to the towns & rural area make 50, not 51. On this basis we recommend a 50 member councillor. The average electorate per councillor in 2018 is 3,395. Single member wards We recommend the use of single member wards wherever possible for the following reasons. Single member wards mean that electors can easily identify and have stronger links with their councillor. Also with the reduction in council size, and consequent increase in electorate per councillor, we believe multi-member wards will be both geographically and numerically too large to be practical. Our recommendations for new boundaries Weston-super-Mare The town centre & the north of Weston Our approach here is to expand the present Central parish ward northwards, to take in the north of the High Street and the area around Weston College. This has the advantage of including the whole of the High Street and the central business district in one ward, to be named Central. -

A Bibliography of Somerset Geology to 1997

A selection from A BIBLIOGRAPHY OF SOMERSET GEOLOGY by Hugh Prudden in alphabetical order of authors, but not titles Copies of all except the items marked with an asterisk* are held by either the Somerset Studies Library or the Somerset Archaeological and Natural History Society June 1997 "Alabaster" in Mining Rev (1837) 9, 163* "Appendix II: geology" in SHERBORNE SCHOOL. Masters and Boys, A guide to the neighbourhood of Sherborne and Yeovil (1925) 103-107 "Blackland Iron Mine" in Somerset Ind Archaeol Soc Bull (Apr 1994) 65, 13 Catalogue of a collection of antiquities ... late Robert Anstice (1846)* Catalogue of the library of the late Robert Anstice, Esq. (1846) 3-12 "Charles Moore and his work" in Proc Bath Natur Hist Antiq Fld Club (1893) 7.3, 232-292 "Death of Prof Boyd Dawkins" in Western Gazette (18 Jan 1929) 9989, 11 "A description of Somersetshire" in A description of England and Wales (1769) 8, 88-187 "Earthquake shocks in Somerset" in Notes Queries Somerset Dorset (Mar 1894) 4.25, 45-47 "Edgar Kingsley Tratman (1899-1978): an obituary" in Somerset Archaeol Natur Hist (1978/79) 123, 145 A fascies study of the Otter Sandstone in Somerset* "Fault geometry and fault tectonics of the Bristol Channel Basin .." in "Petroleum Exploration Soc Gr Brit field trip" (1988)* A few observations on mineral waters .. Horwood Well .. Wincanton (ca 1807) "Ham Hill extends future supplies" in Stone Industries (1993) 28.5, 15* Handbook to the geological collection of Charles Moore ... Bath (1864)* "[Hawkins' sale to the British Museum... libel -

Weston Bay Beach and Dune Management Plan Technical Appendix Wave Modelling

Weston Bay Beach and Dune Management Plan Technical Appendix Wave Modelling June 2013 Draft Report 9Y0510 HASKONING UK LTD. RIVERS, DELTAS & COA STS Stratus House Emperor Way Exeter, Devon EX1 3QS United Kingdom +44 1392 447999 Telephone 01392 446148 Fax [email protected] E-mail www.royalhaskoningdhv.com Internet Document title Weston Bay Beach and Dune Management Plan Technical Appendix Wave Modelling Document short title Wave Modelling Status Draft Report Date June 2013 Project name Weston Bay Beach and Dune Management Plan Project number 9Y0510 Client North Somerset Council Reference 9Y0559/R/303395/Exet Drafted by Martha Gaches and Eddie Crews Checked by Keming Hu Date/initials check …………………. …………………. Approved by Greg Guthrie Date/initials approval …………………. …………………. A company of Royal HaskoningDHV CONTENTS Page 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Location 1 2 INPUT DATA FOR WAVE MODELLING 2 2.1 General 2 2.2 Bathymetry 2 2.3 Tide and Still Water Levels 2 2.4 Wave Data 3 2.4.1 Wave Data Sources 3 2.4.2 Offshore Wave Data 3 2.4.3 Nearshore Wave Data 5 2.4.4 Wave Intpus for Spectral Wave (SW) Modelling 8 3 MIKE 21 SPECTRAL WAVE MODEL SET UP 9 3.1 Model Mesh 9 3.2 Model Bathymetry 10 3.3 Location of Model Result 11 3.4 Offshore boundary conditions 12 4 WAVE MODEL RESULTS 14 5 REFERENCES 17 Appendices Appendix A CCO Nearshore Wave Buoy Data Appendix B SW Wave Modelling Results (Area Plots) Weston Bay Beach and Dune Management Plan Technical Appendix – Wave Modelling Draft Report i June 2013 1 INTRODUCTION This Technical Appendix supports the Weston Bay Beach Management Plan (Weston Bay BMP) commissioned by North Somerset Council (NSC). -

Weston Super Mare Or Ilfracombe Minehead 1730 Penarth 1500 Clevedon 1900 in Glorious Devon

Sailing from MINEHEAD Harbour Porlock Bay WEDNESDAY June 5 Leave 3.45pm back 4.45pm 2010 WEDNESDAY June 19 Leave 2.15pm back 3.15pm Great Days Out Fare: Cruise Porlock Bay £13 SC £11 aboard the famous Lundy Island THURSDAY June 13 Leave 10am back 8.30pm Fare: Visit Lundy Island £39 Paddle Steamer Waverley! Ilfracombe THURSDAY June 13 Leave 10am back 8.30pm Glorious Devon MONDAY June 17 Leave 1pm back 6.45pm Fare: Visit Ilfracombe £27 SC £25 Jun 17: Coach return from Ilfracombe SAILING Sailing from ILFRACOMBE Harbour June 5 until June 25 Lundy Island SUNDAYS June 9 & June 23 THURSDAY June 13 Leave 12.15 back 6.30pm Fare: Visit Lundy Island £35 Exmoor Coast SATURDAY June 15 Leave 2.30pm back 4.45pm Fare: Cruise Exmoor Coast £17 Atlantic Coast THURSDAY June 6 SATURDAY June 22 Leave 1.45pm back 3.15pm Fare: Cruise Atlantic Coast £15 WAVERLEY’s BRISTOL CHANNEL sailings in 2013 WEDNESDAY June 5 SUNDAYS FRIDAY June 14 TUESDAY June 18 Clevedon 1230 June 9 & 23 Porthcawl 1000 Clevedon 0930 Penarth 1400 Jun 9 : Lundy Church Service Ilfracombe 1130/1830 Penarth 1045 Minehead 1545 Jun 8-15: Ilfracombe Victorian Week Porthcawl 2000 Welsh Mountains Cruise Porlock Bay Clevedon 0830 SATURDAY June 15 Welcome Aboard by Steam Train Penarth 0930 Discover the Coasts, Rivers & Islands of the Bristol Minehead 1645/1700 Newport 1000 Ilfracombe 1345/1445 Penarth 1845 Ilfracombe 1215 Penarth 1130 Channel on a magical Day, Afternoon or Evening Cruise. Clevedon 2000 Lundy Island 1400/1630 Ilfracombe 1415/1430 Penarth 1745 Ilfracombe 1830 Cruise Exmoor Coast Clevedon