Lesser Sandhill Crane Account From: Shuford, W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quantifying Crop Damage by Grey Crowned Crane Balearica

QUANTIFYING CROP DAMAGE BY GREY CROWNED CRANE BALEARICA REGULORUM REGULORUM AND EVALUATING CHANGES IN CRANE DISTRIBUTION IN THE NORTH EASTERN CAPE, SOUTH AFRICA. By MARK HARRY VAN NIEKERK Department of the Zoology and Entomology, Rhodes University Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE December 2010 Supervisor: Prof. Adrian Craig i TABLE OF CONTENTS List of tables…………………………………………………………………………iv List of figures ………………………………………………………………………...v Abstract………………………………………………………………………………vii I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................... 1 Species account......................................................................................... 3 Habits and diet ........................................................................................... 5 Use of agricultural lands by cranes ............................................................ 6 Crop damage by cranes ............................................................................. 7 Evaluating changes in distribution and abundance of Grey Crowned Crane………………………………………………………..9 Objectives of the study………………………………………………………...12 II. STUDY AREA…………………………………………………………………...13 Locality .................................................................................................... 13 Climate ..................................................................................................... 15 Geology and soils ................................................................................... -

First Arizona Record of Common Crane

Arizona Birds - Journal of Arizona Field Ornithologists Volume 2020 FIRST ARIZONA RECORD OF COMMON CRANE JOE CROUSE,1125 W. SHULLENBARGER DR., FLAGSTAFF, AZ 86005 The first record of a Common Crane (Grus grus), a Eurasian species, in Arizona was reported in May 2017 at Mormon Lake in Coconino County. It remained at this lake through September 2017. In 2019 a Common Crane was reported 11 May through 31 August at Mormon Lake. The 2017 record has been reviewed and accepted by the Arizona Bird Committee (Rosenberg et al. 2019), and the 2019 bird has been accepted as the same individual. The Common Crane is a widespread crane found in Europe, Asia, the Middle East, and North Africa. Breeding occurs across northern Europe and northern Asia, from Norway on the west to Siberia on the east. Nonbreeding populations are found as far west as Morocco and to southeastern China. A resident population exists in Turkey (NatureServe and IUCN 2017, Figure 1). Preferred habitat for both breeding and nonbreeding birds is small ponds or lakes, wet meadows, and other wetland areas (Cramp and Simmons 1980). Figure 1. Common Crane Distribution Cramp and Simmons (1980) stated that the Common Crane range in western Europe has had a “marked” decrease since the Middle Ages. They attributed this to the draining of nesting areas. Since 1950 improved habitat protections, recolonization in previously inhabited areas, and designation as a protected species have resulted in a dramatic increase in the overall population (Prange 2005). Although its range has decreased, it continues to be extensive enough, along with the increase in its already large population, to give it the status of a species of “Least Concern” (BirdLife International 2016, NatureServe and IUCN 2019). -

Fernald Preserve Bird List

Bird List Order: ANSERIFORMES Order: PODICIPEDIFORMES Order: GRUIFORMES Order: COLUMBIFORMES Family: Anatidae Family: Podicipedidae Family: Rallidae Family: Columbidae Black-bellied Whistling Duck Pied-billed Grebe Virginia Rail Rock Pigeon Greater White-fronted Goose Horned Grebe Sora Mourning Dove Snow Goose Red-necked Grebe Common Gallinule Order: CUCULIFORMES Ross’s Goose American Coot Order: SULIFORMES Family: Cuculidae Cackling Goose Family: Gruidae Family: Phalacrocoracidae Yellow-billed Cuckoo Canada Goose Sandhill Crane Mute Swan Double-crested Cormorant Black-billed Cuckoo Trumpeter Swan Order: CHARADRIIFORMES Order: PELECANIFORMES Order: STRIGIFORMES Tundra Swan Family: Recurvirostridae Family: Ardeidae Family: Tytonidae Wood Duck Black-necked Stilt American White Pelican Barn Owl Gadwall Family: Charadriidae American Bittern Family: Strigidae Eurasian Wigeon Black-bellied Plover Least Bittern Eastern Screech-Owl American Wigeon American Golden Plover Great Blue Heron Great Horned Owl American Black Duck Semipalmated Plover Great Egret Barred Owl Mallard Killdeer Snowy Egret Long-eared Owl Blue-winged Teal Family: Scolopacidae Little Blue Heron Short-eared Owl Norther Shoveler Spotted Sandpiper Cattle Egret Northern Saw-whet Owl Northern Pintail Solitary Sandpiper Green Heron Garganey Greater Yellowlegs Order: CAPRIMULGIFORMES Black-crowned Night-Heron Green-winged Teal Willet Family: Caprimulgidae Canvasback Family: Threskiornithidae Lesser Yellowlegs Common Nighthawk Glossy Ibis Redhead Upland Sandpiper Ring-necked Duck White-faced -

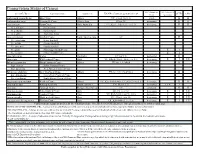

Conservation Status of Cranes

Conservation Status of Cranes IUCN Population ESA Endangered Scientific Name Common name Continent IUCN Red List Category & Criteria* CITES CMS Trend Species Act Anthropoides paradiseus Blue Crane Africa VU A2acde (ver 3.1) stable II II Anthropoides virgo Demoiselle Crane Africa, Asia LC(ver 3.1) increasing II II Grus antigone Sarus Crane Asia, Australia VU A2cde+3cde+4cde (ver 3.1) decreasing II II G. a. antigone Indian Sarus G. a. sharpii Eastern Sarus G. a. gillae Australian Sarus Grus canadensis Sandhill Crane North America, Asia LC II G. c. canadensis Lesser Sandhill G. c. tabida Greater Sandhill G. c. pratensis Florida Sandhill G. c. pulla Mississippi Sandhill Crane E I G. c. nesiotes Cuban Sandhill Crane E I Grus rubicunda Brolga Australia LC (ver 3.1) decreasing II Grus vipio White-naped Crane Asia VU A2bcde+3bcde+4bcde (ver 3.1) decreasing E I I,II Balearica pavonina Black Crowned Crane Africa VU (ver 3.1) A4bcd decreasing II B. p. ceciliae Sudan Crowned Crane B. p. pavonina West African Crowned Crane Balearica regulorum Grey Crowned Crane Africa EN (ver. 3.1) A2acd+4acd decreasing II B. r. gibbericeps East African Crowned Crane B. r. regulorum South African Crowned Crane Bugeranus carunculatus Wattled Crane Africa VU A2acde+3cde+4acde; C1+2a(ii) (ver 3.1) decreasing II II Grus americana Whooping Crane North America EN, D (ver 3.1) increasing E, EX I Grus grus Eurasian Crane Europe/Asia/Africa LC unknown II II Grus japonensis Red-crowned Crane Asia EN, C1 (ver 3.1) decreasing E I I,II Grus monacha Hooded Crane Asia VU B2ab(I,ii,iii,iv,v); C1+2a(ii) decreasing E I I,II Grus nigricollis Black-necked Crane Asia VU C2a(ii) (ver 3.1) decreasing E I I,II Leucogeranus leucogeranus Siberian Crane Asia CR A3bcd+4bcd (ver 3.1) decreasing E I I,II Conservation status of species in the wild based on: The 2015 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, www.redlist.org CRITICALLY ENDANGERED (CR) - A taxon is Critically Endangered when it is facing an extremely high risk of extinction in the wild in the immediate future. -

Near-Ultraviolet Light Reduced Sandhill Crane Collisions with a Power Line by 98% James F

AmericanOrnithology.org Volume XX, 2019, pp. 1–10 DOI: 10.1093/condor/duz008 RESEARCH ARTICLE Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/condor/advance-article-abstract/doi/10.1093/condor/duz008/5476728 by University of Nebraska Kearney user on 09 May 2019 Near-ultraviolet light reduced Sandhill Crane collisions with a power line by 98% James F. Dwyer,*, Arun K. Pandey, Laura A. McHale, and Richard E. Harness EDM International, Fort Collins, Colorado, USA *Corresponding author: [email protected] Submission Date: 6 September, 2018; Editorial Acceptance Date: 25 February, 2019; Published May 6, 2019 ABSTRACT Midflight collisions with power lines impact 12 of the world’s 15 crane species, including 1 critically endangered spe- cies, 3 endangered species, and 5 vulnerable species. Power lines can be fitted with line markers to increase the visi- bility of wires to reduce collisions, but collisions can persist on marked power lines. For example, hundreds of Sandhill Cranes (Antigone canadensis) die annually in collisions with marked power lines at the Iain Nicolson Audubon Center at Rowe Sanctuary (Rowe), a major migratory stopover location near Gibbon, Nebraska. Mitigation success has been limited because most collisions occur nocturnally when line markers are least visible, even though roughly half the line markers present include glow-in-the-dark stickers. To evaluate an alternative mitigation strategy at Rowe, we used a randomized design to test collision mitigation effects of a pole-mounted near-ultraviolet light (UV-A; 380–395 nm) Avian Collision Avoidance System (ACAS) to illuminate a 258-m power line span crossing the Central Platte River. We observed 48 Sandhill Crane collisions and 217 dangerous flights of Sandhill Crane flocks during 19 nights when the ACAS was off, but just 1 collision and 39 dangerous flights during 19 nights when the ACAS was on. -

Status and Harvests of Sandhill Cranes: Mid-Continent, Rocky Mountain, Lower Colorado River Valley and Eastern Populations

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service StatusU.S. Fish & Wildlife and Service Harvests of SandhillStatus and Cranes Harvests of Mid-continent,Sandhill Cranes Rocky Mountain, Lower Colorado River Valley and STATUS2008 and Mid-continent, HARVESTS Rocky EasternMountain, Populations and Lower Colorado River Valleyof Populations SANDHILL CRANES MID-CONTINENT, ROCKY MOUNTAIN, and LOWER COLORADO RIVER VALLEY POPULATIONS 2008 Division of Migratory Bird Management U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Central Flyway Representative P.O. Box 25486, DFC Denver, Colorado 80225 Acknowledgments This report provides population status, recruitment indices, harvest trends, and other management information for the Mid-Continent (MCP), Rocky Mountain (RMP), Lower Colorado River Valley (LCRVP), and Eastern (EP) populations of sandhill cranes. Information was compiled with the assistance of a large number of biologists from across North America. We acknowledge the contributions of: D.P. Collins, P. Donnelly, J.L. Drahota, D.L. Fronczak, T.S. Liddick, and P.P. Thorpe for conducting annual aerial population surveys; W.M. Brown and K.L. Kruse for conducting the RMP productivity survey; K.A. Wilkins and M.H. Gendron for conducting the U.S. and Canadian Federal harvest surveys for the MCP; S. Olson and D. Olson for compiling harvest information collected on sandhill cranes in the Pacific Flyway; J. O’Dell for compiling information for the LCRVP; T. Cooper, S. Kelly and D.L. Fronczak for compiling population information for the EP; and D.S. Benning, R.C. Drewien and D.E. Sharp for their career-long commitment to sandhill crane management. We especially want to recognize the support of the state and provincial biologists in the Central and Pacific Flyways for the coordination of sandhill crane hunting programs and especially the distribution of crane hunting permits and assistance in conducting of annual cooperative surveys. -

The Cranes Compiled by Curt D

Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan The Cranes Compiled by Curt D. Meine and George W. Archibald IUCN/SSC Crane Specialist Group IUCN The World Conservation Union IUCN/Species Survival Commission Donors to the SSC Conservation Communications Fund and The Cranes: Status Survey & Conservation Action Plan The IUCN/Species Survival Commission Conservation Communications Fund was established in 1992 to assist SSC in its efforts to communicate important species conservation information to natural resource managers, deci- sion-makers and others whose actions affect the conservation of biodiversity. The SSC's Action Plans, occasional papers, news magazine (Species), Membership Directory and other publi- cations are supported by a wide variety of generous donors including: The Sultanate of Oman established the Peter Scott IUCN/SSC Action Plan Fund in 1990. The Fund supports Action Plan development and implementation; to date, more than 80 grants have been made from the Fund to Specialist Groups. As a result, the Action Plan Programme has progressed at an accelerated level and the network has grown and matured significantly. The SSC is grateful to the Sultanate of Oman for its confidence in and sup- port for species conservation worldwide. The Chicago Zoological Society (CZS) provides significant in-kind and cash support to the SSC, including grants for special projects, editorial and design services, staff secondments and related support services. The President of CZS and Director of Brookfield Zoo, George B. Rabb, serves as the volunteer Chair of the SSC. The mis- sion of CZS is to help people develop a sustainable and harmonious relationship with nature. The Zoo carries out its mis- sion by informing and inspiring 2,000,000 annual visitors, serving as a refuge for species threatened with extinction, developing scientific approaches to manage species successfully in zoos and the wild, and working with other zoos, agencies, and protected areas around the world to conserve habitats and wildlife. -

Phylogeny of Cranes (Gruiformes: Gruidae) Based on Cytochrome-B Dna Sequences

The Auk 111(2):351-365, 1994 PHYLOGENY OF CRANES (GRUIFORMES: GRUIDAE) BASED ON CYTOCHROME-B DNA SEQUENCES CAREY KRAJEWSKIAND JAMESW. FETZNER,JR. • Departmentof Zoology,Southern Illinois University, Carbondale,Illinois 62901-6501, USA ABS?RACr.--DNAsequences spanning 1,042 nucleotide basesof the mitochondrial cyto- chrome-b gene are reported for all 15 speciesand selected subspeciesof cranes and an outgroup, the Limpkin (Aramusguarauna). Levels of sequencedivergence coincide approxi- mately with current taxonomicranks at the subspecies,species, and subfamilial level, but not at the generic level within Gruinae. In particular, the two putative speciesof Balearica (B. pavoninaand B. regulorum)are as distinct as most pairs of gruine species.Phylogenetic analysisof the sequencesproduced results that are strikingly congruentwith previousDNA- DNA hybridization and behavior studies. Among gruine cranes, five major lineages are identified. Two of thesecomprise single species(Grus leucogeranus, G. canadensis), while the others are speciesgroups: Anthropoides and Bugeranus;G. antigone,G. rubicunda,and G. vipio; and G. grus,G. monachus,G. nigricollis,G. americana,and G. japonensis.Within the latter group, G. monachusand G. nigricollisare sisterspecies, and G. japonensisappears to be the sistergroup to the other four species.The data provide no resolutionof branchingorder for major groups, but suggesta rapid evolutionary diversification of these lineages. Received19 March 1993, accepted19 August1993. THE 15 EXTANTSPECIES of cranescomprise the calls.These -

Periodic Status Review for the Sandhill Crane

STATE OF WASHINGTON January 2017 Periodic Status Review for the Sandhill Crane Derek W. Stinson Washington Department of FISH AND WILDLIFE Wildlife Program The Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife maintains a list of endangered, threatened, and sensitive species (Washington Administrative Codes 232-12-014 and 232-12-011). In 1990, the Washington Wildlife Commission adopted listing procedures developed by a group of citizens, interest groups, and state and federal agencies (Washington Administrative Code 232-12-297. The procedures include how species list- ings will be initiated, criteria for listing and delisting, a requirement for public review, the development of recovery or management plans, and the periodic review of listed species. The Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife is directed to conduct reviews of each endangered, threat- ened, or sensitive wildlife species at least every five years after the date of its listing by the Washington Fish and Wildlife Commission. The periodic status reviews are designed to include an update of the species status report to determine whether the status of the species warrants its current listing status or deserves reclas- sification. The agency notifies the general public and specific parties who have expressed their interest to the Department of the periodic status review at least one year prior to the five-year period so that they may submit new scientific data to be included in the review. The agency notifies the public of its recommenda- tion at least 30 days prior to presenting the findings to the Fish and Wildlife Commission. In addition, if the agency determines that new information suggests that the classification of a species should be changed from its present state, the agency prepares documents to determine the environmental consequences of adopting the recommendations pursuant to requirements of the State Environmental Policy Act. -

Sandhill Crane ASSESSING HABITAT QUALITY for PRIORITY WILDLIFE SPECIES in COLORADO WETLANDS

COLORADO PARKS & WILDLIFE Sandhill Crane ASSESSING HABITAT QUALITY FOR PRIORITY WILDLIFE SPECIES IN COLORADO WETLANDS Species Distribution Range Sandhill cranes breed in a variety of northern regions, including northwestern Colorado. During migration, sandhill cranes can occur almost anywhere in Colorado. ? © MICHAEL MENEFEE, CNHP MENEFEE, MICHAEL © Sandhill cranes (Grus canadensis, Family Gruidae) are impressive birds with a wide wingspan, red eye patch, and loud trumpeting call. items include snails, crayfish, insects, Species Description roots, tubers, small vertebrates, and Identification waterfowl eggs. With a length of 3½–4 feet and wing- Breeding span of 6–7 feet, sandhill cranes are Conservation Status Year-round hard to miss, but they are sometimes There are several subspecies of sandhill Nonbreeding mistaken for great blue herons. Their crane. The greater sandhill crane G.( graceful dancing helps establish and c. tabida), listed as a Tier 1 Species of maintain pair bonds, which last a life- Greatest Conservation Need in Colo- time, and their warbling or trumpeting rado (CPW 2015), winters primarily calls can be heard from a mile away. in New Mexico, with spring and fall stopovers in the San Luis Valley of Preferred Habitats Colorado. Grus c. canadensis migrates Sandhill cranes occupy numerous through the eastern plains of Colorado. wetland habitats, including emergent Although two other subspecies (G. c. marshes, seeps and springs, wet mead- pulla and G. c. nesiotes) are Federally ows, moist soil units, playas, reservoirs, endangered, sandhill crane popula- and streams. They rely heavily on grain tions appear to be stable or increasing crops; therefore, wetlands close to in most areas. In Colorado, breeding crops are preferred. -

Volume III, Chapter 14 Sandhill Crane

Volume III, Chapter 14 Sandhill Crane TABLE OF CONTENTS 14.0 Sandhill Crane (Grus Canadensis)............................................................................ 14-1 14.1 Introduction ........................................................................................................... 14-1 14.2 Description ............................................................................................................ 14-2 14.3 Distribution............................................................................................................ 14-4 14.3.1 North America ................................................................................................ 14-4 14.3.2 Washington ..................................................................................................... 14-5 14.4 Natural History...................................................................................................... 14-7 14.4.1 Reproduction................................................................................................... 14-7 14.4.2 Longevity & Mortality .................................................................................... 14-9 14.4.3 Migration & Dispersal ................................................................................. 14-12 14.4.4 Foraging & Food.......................................................................................... 14-15 14.5 Habitat Requirements .......................................................................................... 14-16 14.5.1 Breeding....................................................................................................... -

Greater Sandhill Crane ASSESSING HABITAT QUALITY for PRIORITY WILDLIFE SPECIES in COLORADO WETLANDS

COLORADO PARKS & WILDLIFE Greater Sandhill Crane ASSESSING HABITAT QUALITY FOR PRIORITY WILDLIFE SPECIES IN COLORADO WETLANDS Species Distribution Range The RMP breeds throughout the Rocky Mountains. In Colorado, they breed primarily in Routt, Moffat, Rio Blanco, and Jackson Counties. Increasing numbers winter near Delta and in the San Luis Valley. During migration, the San Luis Valley provides important stopover habitat. © MICHAEL MENEFEE, CNHP MENEFEE, MICHAEL © Greater sandhill cranes (Antigone canadensis tabida, Family Gruidae) are impressive birds with a wide wingspan, red eye patch, and loud trumpeting call. Breeding Key staging area Migration habitats, including wet meadows, sea- Key stopover site Species Description sonal wetlands, and croplands. Nonbreeding Identification Year-round With a height of 4½–5 feet and a Diet wingspan of 6–7 feet, sandhill cranes Food items include but are not limited are hard to miss, but with mostly gray to snails, crayfish, insects, roots, tubers, plumage and long legs and neck, they small vertebrates, and waterfowl eggs. are sometimes mistaken for great During migration and winter, sandhill blue herons. Their graceful dancing cranes exploit agricultural crops, helps establish and maintain pair including corn, wheat, barley, potatoes, bonds, which last a lifetime, and their and alfalfa. warbling or trumpeting calls can be heard from a mile away. Conservation Status Greater sandhill cranes in Colorado North America map used by permission from Birds of Preferred Habitats belong to the Rocky Mountain