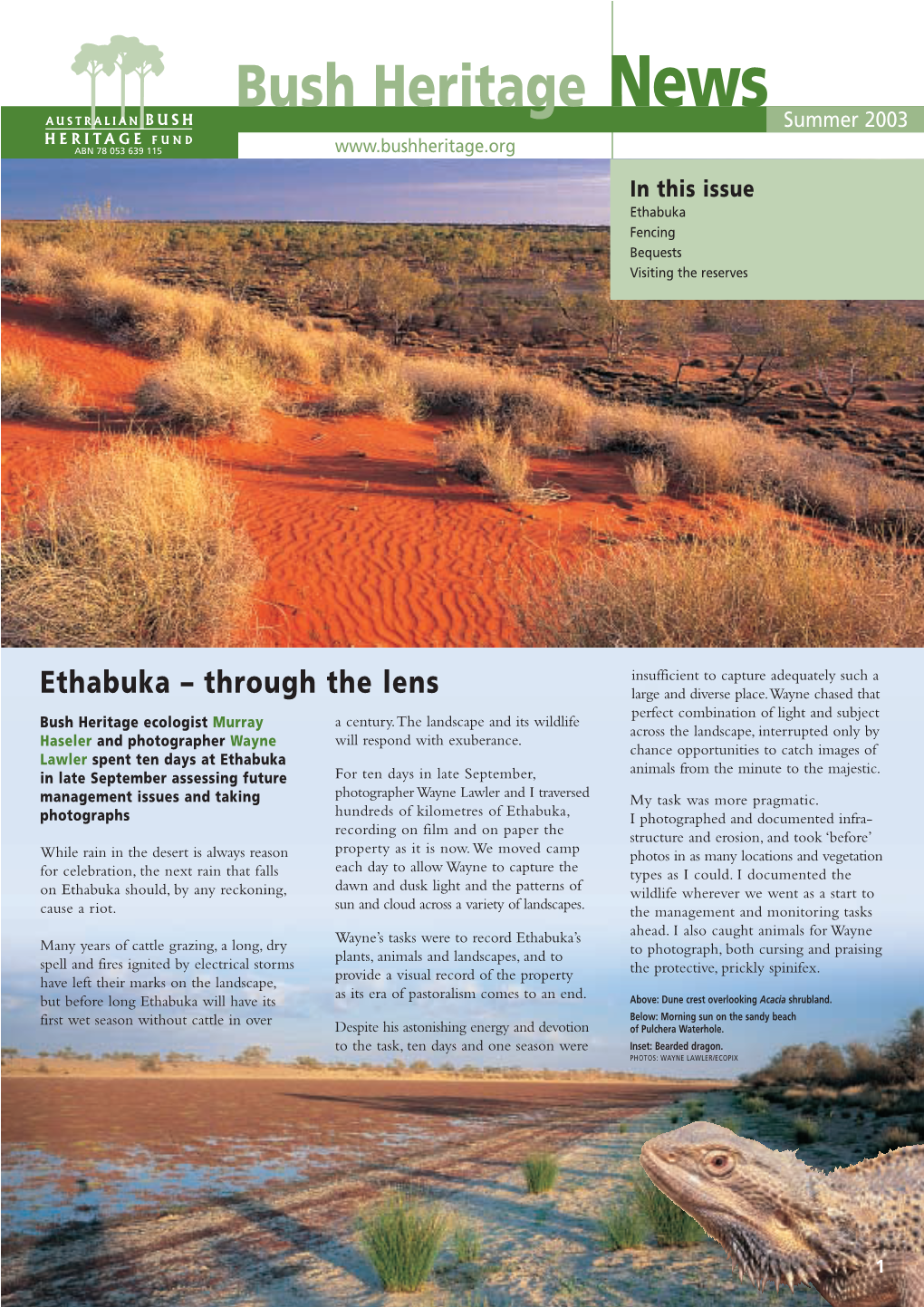

Bush Heritage News Summer 2003

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Autumn 2016 Bushheritage.Org.Au from the CEO Bush Heritage Australia Who We Are Twenty-Five Years Ago, a Small Group There Is So Much More to Do

BUSH TRACKS Bush Heritage Australia’s quarterly magazine for active conservation Maggie nose best Tracking feral cats Since naturalist John Young’s rediscovery Evidence suggests that feral cat density on of the population in 2013, a recovery the property is low, but there are at least two in Queensland team led by Bush Heritage Australia, and individuals prowling close to where Night Meet Maggie, a four-legged friend working ornithologists Dr Steve Murphy and Allan Parrots roost during the day. Just one feral hard to protect the world’s only known Burbidge, have been working tirelessly to cat that develops a taste for Night Parrots population of Night Parrots on our newest bring the species back from the brink of would be enough to drive this population, reserve, secured recently with the help of extinction. The first step – to purchase the and possibly the species, into extinction. Bush Heritage supporters. land where this elusive population live – Continued on page 3 has been taken, thanks to Bush Heritage It’s 3am. The sun won’t appear for hours, donors, and the reserve is now under In this issue but for Mark and Glenys Woods and their intensive and careful management. 4 Happy 10th birthday Cravens Peak ever-loyal companion Maggie, work is 8 Discovering the Dugong about to begin. The priority since the purchase has been 9 By the light of the moon managing threats to the Night Parrot After a quick breakfast they jump in the ute 10 Apples and androids: The future population, chiefly feral cats. of wildlife monitoring? and drive 45 minutes to the secret location 11 Bob Brown’s photographic journey in western Queensland where the world’s Mark Woods and trusty companion Maggie are of our reserves only known population of Night Parrots helping in the fight to protect the Night Parrot 12 Yourka family camp has survived. -

Bushtracks Bush Heritage Magazine | Summer 2019

bushtracks Bush Heritage Magazine | Summer 2019 Outback extremes Darwin’s legacy Platypus patrol Understanding how climate How a conversation beneath Volunteers brave sub-zero change will impact our western gimlet gums led to the creation temperatures to help shed light Queensland reserves. of Charles Darwin Reserve. on the Platypus of the upper Murrumbidgee River. Bush Heritage acknowledges the Traditional Owners of the places in which we live, work and play. We recognise and respect the enduring relationship they have with their lands and waters, and we pay our respects to elders, past and present. CONTRIBUTORS 1 Ethabuka Reserve, Qld, after rains. Photo by Wayne Lawler/EcoPix Chris Grubb Clare Watson Dr Viki Cramer Bron Willis Amelia Caddy 2 DESIGN Outback extremes Viola Design COVER IMAGE Ethabuka Reserve in far western Queensland. Photo by Lachie Millard / 8 The Courier Mail Platypus control This publication uses 100% post- 10 consumer waste recycled fibre, made Darwin’s legacy with a carbon neutral manufacturing process, using vegetable-based inks. BUSH HERITAGE AUSTRALIA T 1300 628 873 E [email protected] 13 W www.bushheritage.org.au Parting shot Follow Bush Heritage on: few years ago, I embarked on a scientific they describe this work reminds me that we are all expedition through Bush Heritage’s Ethabuka connected by our shared passion for the bush and our Aa Reserve, which is located on the edge of the dedication to seeing healthy country, protected forever. Simpson Desert, in far western Queensland. We were prepared for dry conditions and had packed ten Over the past 27 years, this same passion and days’ worth of water, but as it happened, our visit to dedication has seen Bush Heritage grow from strength- Ethabuka coincided with a rare downpour – the kind to-strength through two evolving eras of leadership of rain that transforms desert landscapes. -

Abhf Summer Nl 05

Bush Heritage News Summer 2005 ABN 78 053 639 115 www.bushheritage.org Lake Eyre.The colours and the In this issue Our latest purchase vastness of the landscape took my Cravens Peak – another bit of the breath away. Rich ochres of every hue and cobalt-blue sky seemed to Anchors in the landscape Outback stretch into infinity. Charles Darwin Reserve weeding bee Bush Heritage’s latest reserve, I was standing on the edge of the Cravens Peak, is ‘just down the Channel Country, that highly metropolitan Melbourne or Sydney) road’ from Ethabuka Reserve in productive region of Queensland and also the most expensive because far-western Queensland but, as famous for fattening cattle, and for of the ‘value’ of the Channel Country. Conservation Programs Manager this reason so far poorly reserved. We still have a great deal of money Paul Foreman points out, this new I contemplated the significance to raise! pastoral lease is very different of Bush Heritage’s buying and protecting some of this valuable Cravens Peak is now our most diverse On my first visit to Cravens Peak ecosystem at Cravens Peak Station, reserve, in both its geomorphology Station in May this year I stood where the Mulligan River plains and biology. It is an exciting acquisition on an outcrop of the Toko Range are still relatively intact. and presents us with an unprecedented and gazed over the source of the management challenge. Mulligan River.This is one of the On 31 October 2005 Cravens Peak headwaters of the immense Cooper became the 21st Bush Heritage Creek system that braids its way reserve. -

WWF0107 the Web Summer.Indd

THE WEB The national newsletter for the Threatened Species Network WELCOME TO SUMMER 2007 The Threatened Species Network is a community -based program of the Australian Government and WWF-Australia Lord Mayor of Sydney Clover Moore MP, WWF-Australia CEO Greg Bourne and Earth Hour Youth Ambassador Sarah Bishop at the launch of Earth Hour on 15 December 2006. Sarah Bishop will walk from Brisbane to Sydney in early 2007 as a way of voicing young Australians’ concerns about global warming. During the two-month, 1000-kilometre walk, Sarah will exchange ideas and make presentations to communities along the way, illustrating the simple things people can do to make a difference. © WWF/Tanya Lake. COMMUNITY ACTION ON CLIMATE CHANGE By Katherine Howard, TSN Program Officer, WWF-Australia Welcome to the Summer Web! In the last couple of editions we’ve talked about the topic that’s on everyone’s lips – climate change. Here at the TSN we are very excited about an upcoming event called Earth Hour, organised by WWF-Australia and Fairfax Publishing. At 7.30 pm on 31 March, businesses and households all over Sydney will switch off their lights for one hour. Earth Hour is part of a major effort CONTENTS to reduce Sydney’s greenhouse gas pollution by 5% in one year, and will send NATIONAL NEWS a very powerful message that it is possible to take action against global warming. What’s On 2 The threat of climate change needs to be tackled by a two-pronged approach: mitigation and adaptation. We REGIONAL NEWS need to both lower our greenhouse emissions to reduce the extent of climate change (mitigation) and to build SA 3 the resilience of our native species and natural ecosystems to the changed conditions (adaptation).1 The TSN’s Queensland 4 speciality is community-based, on-ground conservation, so we particularly focus on building resilience, but we Arid Rangelands 6 certainly haven’t forgotten how crucial it is to also reduce our emissions of greenhouse gases. -

25-Year Anniversary Newsletter

From little things... 25 Years of Bush Heritage Australia 25 years Front cover: Laila and Skye Palmer, daughters of Scottsdale Reserve Manager Phil Palmer, with volunteer Will Douglas at Scottsdale Reserve, NSW. See inside back cover for their story. Photo by Anna Carlile. This page: Numerous Bush Heritage reserves across Australia protect the habitat of the Sugar Glider, shown here nesting in a tree hollow. Photo by Steve Parish. From little things... Contents 2 18 1 Bob Brown Rod and Annette PROFILE PROFILE Founder Donors 4 20 Gerard O’Neil Sydney University PROFILE at Ethabuka CEO CASE STUDY Research partnership 6 A Giant Leap 26 CASE STUDY Heike Eberhard Red-tailed Phascogale PROFILE Volunteer 8 Partners in 28 conservation Olivia Barratt CASE STUDY PROFILE Indigenous partnership Young Advocate 12 30 Timeline Cover story 25 YEARS PROFILE 14 Contributing writers Leigh Johnstone Boolcoomatta is like Kate Cranney a homecoming CASE STUDY Boolcoomatta 25 years 2 From little things... Bob Brown A true success story PROFILE In the very early days of Bush Heritage Over the years, as I moved from the tiller 3 Founder Australia, I remember buying a black and to become its patron, Bush Heritage has white strip advertisement in the Business been blessed with talented Directors, Review Weekly. I had just bought the CEOs and staff, a committed Board and an two properties in the Liffey Valley and army of volunteers and donors who have our very small team was helping me raise put us at the forefront of environmental money to meet the loan repayments. science and practical conservation. -

Bush Heritage News Edgbaston Reserve »» Focus on Bon Bon Station Reserve Summer 2009 »» Enter Our Competition!

www.bushheritage.org.au In this issue » Bio-blitz at Yourka Reserve » New discoveries from Bush Heritage News Edgbaston Reserve » Focus on Bon Bon Station Reserve Summer 2009 » Enter our competition! Getting to grips with Yourka Reserve Queensland Herbarium botanist Jeanette Kemp joined Above: Staff members (L-R) Jim Radford, Ecological Monitoring Coordinator Jim Radford and Clair Dougherty and Paul Foreman undertaking vegetation survey in eucalypt woodlands of Yourka other Bush Heritage staff in an exploration of one of Reserve, Qld. PHOTO: JEN GRINdrod. Inset: Scenic landform and vegetation of Yourka Reserve, Bush Heritage’s newest reserves. Qld. PHOTO: WayNE LawlER/ECOPIX. hump! We felt the jolt of the Hilux and potholes into the tracks around The primary aim of the blitz was to learn Tshuddering to an abrupt stop before Yourka Reserve had also delayed more about the ecology of Yourka by we registered the sound of the front axle ecological surveys because much of gathering information from focused field ramming into the chalky roadbed as the the reserve was inaccessible until surveys and investigation. An intensive track gave way beneath us. Opening autumn. When we arrived we could mammal survey program, using infra-red the doors, we tumbled out into a gaping see flood debris, including uprooted motion-triggered cameras, cage traps and spotlighting, was conducted in the hole in the road. The deceptively solid trees, lodged in the limbs of towering moist forests and woodlands in the east surface was merely a thin crust over paperbarks and river she-oaks a full of the property. Although the presence a treacherous pothole, excavated by 20 m above the creeks. -

Spring 2011 Newsletter

BUSH HERITAGE Thank you for 20 years of conservation Special edition Spring 2011 www.bushheritage.org.au Bob Brown Founder of Bush Heritage Australia Bob Brown at Oura Oura Photograph by Peter Morris I walked through a gully dense with Thanks to you, Bush Heritage has “I’ve supported Bush rainforest and carpeted by ferns. weathered the seasons along the Heritage for 20 years” A small creek bubbled away nearby. road to today, our 20th anniversary. I found some hand-worked shards of I’d like to invite you to celebrate your stone – a reminder of the Aboriginal part in those 20 years. In this newsletter, “I was walking in Tasmania’s Liffey Valley people who’d been going there for you’ll see stories of others who love our on a sunny day in 1990 when I made a thousands of years, to enjoy the morning bush just like you do.” decision that began the journey we now sun. I felt a connection with humanity that know as Bush Heritage Australia. stretched back to generations past, and “These are your stories – forward to generations yet to come. I often walked in the bush to collect my I couldn’t stand by and watch that spirit the stories of our bush, thoughts – I still do. On that day, I was die. With encouragement and support walking high above two beautiful bush our creatures and our people, from a group of like-minded friends, blocks that had come up for sale and I decided to go into debt to buy this from 20 years of conservation.” that logging companies were keen to natural part of the Australian bush. -

Winter 2015 Newsletter

BUSH TRACKS Bush Heritage Australia’s quarterly magazine for active conservation Double the impact in outback wetlands A black-winged stilt, photographed here at Naree, is among the native birds to use these wetlands. Photo Peter Morris. On most days if you could see our A major rain event – enough to flood the “At the moment there’s a lot of red sand, Naree Station Reserve, or neighbouring ephemeral wetlands and flip their natural cycle silver trees and very dry grass. The heart Yantabulla Station, it would be hard to into a ‘boom’ – only happens once every five to of it is still wet though,” says Sue Akers. believe the parched outback landscape ten years. In between it’s a very different story. Sue and husband David are our managers transforms into one of Australia’s most at Naree. Walking into the wetlands when they’re breathtaking inland wetlands, teeming dry, as they are now, is an extraordinary Earlier this year we had our first glimpse with water birds. experience. Ancient black box, coolabah since Bush Heritage purchased Naree in These properties sit at the heart of trees and elegant yapunyahs are found 2012 of just how quickly these ephemeral the Paroo-Warrego wetlands (the last around the swamp margins. The deeper you wetlands can transform. remaining free-flowing river catchment go the larger the river wattles and tangled in the Murray-Darling Basin) about lignum shrubs become. In certain spots you In this issue 150km north-west of Bourke in NSW. can see dozens of old nesting platforms left 4 Science: Expanding our horizons behind by previous generations of waterbirds. -

Biodiversity Hotspots

Biodiversity Hotspots 15 1 14 13 2 12 3 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 1 Einasleigh and Desert Uplands 6 South East of South Australia 11 Mount Lesueur Eneabba and South West Victoria 2 Brigalow North and South 7 Mt Lofty / Kangaroo Island 12 Geraldton to Shark Bay sand plains 3 Border Ranges North and South 8 Fitzgerald River Ravensthorpe 13 Carnarvon Basin 4 Midlands of Tasmania 9 Busselton Augusta 14 Hamersley / Pilbara 5 Victorian Volcanic Plain 10 Central and Eastern Avon Wheat Belt 15 North Kimberley Data s ource: Australia, Digital Elevation Model (DEM) 9 seconds (c) Geoscience Australia, 1996. All rights reserved. Topographic Data - Australia - 1:10 million (c) Geoscience Australia, 1989. All rights reserved. Caveats: Data used are assumed to be correct as received from the data suppliers. The Department of Environment and Heritage doesnot representor warrantthat the Data is accurate,complete, current or suitable for any purpose. (c) Commo nwe a lt h of A ust ra lia 20 0 3 Map produced by ERIN, Department of Environment and Heritage,Canberra, August 2003. Australia's 15 National Biodiversity Hotspots 1. Einasleigh and Desert Uplands (Queensland) In this region of North Queensland, the high ranges and plateaus of Einasleigh contrast sharply with the plains and low ranges of the Desert Uplands. Einasleigh basalt lava flows and lava tunnels provide habitat for threatened and geographically restricted plants and animals. Water enters the Great Artesian Basin aquifers here and important artesian spring complexes contain endemic plants, snails and fish including the Edgbaston Goby and the plant Salt Pipewort (Eriocaulon carsonii). -

2009–10 Conservation Report

365 Days ANNUAL CONSERVATION REPORT 2009–2010 The sun rises over forested ridges at Yourka Reserve Photograph by Wayne Lawler / Ecopix 3 CEO’s Report “This year, images of our western Queensland reserves in fl ood have gone around the world. Our presence and profi le in the media has grown and our support base has increased as more of our supporters share the Bush Heritage story.” Doug Humann, Chief Executive Offi cer My fi rst view of the far-west Queensland property These changes refl ect larger changes in the of Ethabuka Reserve was from 6000 ft above the landscape under Bush Heritage’s stewardship. ground. It was 2002 and we were assessing the A recent report on our fi rst fi ve years of management 213,300-hectare property by light plane, in view at Ethabuka illustrates how our practical science of a potential purchase. The desert loomed as a and management is driving conservation outcomes: veil of red approaching from the dusty clay of the protected springs; reduced impacts of feral animals; Diamantina channel country. The dunes were and return of rarely seen fauna such as the desert devoid of vegetation following recent massive short-tailed mouse (read about it on page 17). wildfi res. The earth was parched, the cattle poorly At the same time we are building relationships nourished and an air of desperation hung over with partners, neighbours and collaborators: the the landscape. country’s traditional owners (the Wangkamadla In 2010 Ethabuka’s landscape tells a very different people, who’ve recently conducted cultural values story. -

Ethabuka Reserve Manager ROLE GRADE

Position Description – Reserve Manager Ethabuka Bush Heritage Australia POSITION DESCRIPTION POSITION TITLE: Ethabuka Reserve Manager ROLE GRADE: 7 COST CENTRE: North $69-72k (inclusive of 9.5% superannuation) REMUNERATION: commensurate with qualifications and experience) LOCATION: Ethabuka Reserve DATE REVIEWED: December 2017 POSITION BASIS: Full time 1.0 FTE, ongoing Introduction Bush Heritage Australia is a national non-profit organisation protecting the natural environment through the management of land and water of high conservation value. This is achieved through three complementary strategies: directly purchasing land that has outstanding conservation values, purchasing and revegetating land that will reconnect fragmented landscapes and building partnerships with other landowners, particularly traditional owners. Bush Heritage works across 19 priority landscapes and owns around 1.2 million hectares of reserves. In addition we partner with Aboriginal and agricultural landowners to achieve conservation outcomes. Currently, Bush Heritage is working across more than 6.2 million hectares in our priority landscapes. Established in 1991, Bush Heritage has around 30,000 supporters Australia wide and an annual operating budget of over $20 million. Bush Heritage is primarily funded by donations from individuals and philanthropic sources. In pursuing its mission, Bush Heritage engages staff and volunteers across all the States and mainland Territories of Australia. Bush Heritage’s culture requires a commitment to a collaborative and supportive approach to leadership and management, with a strong commitment to safety and the development of our people. Page 1 of 5 Position Description – Reserve Manager Ethabuka Bush Heritage Australia Our values are: Conservation: Conservation impact is essential. Our decisions are informed by best available science and evidence; Culture: We respectfully engage with Traditional Owners of the land, and recognise Aboriginal culture, connection to Country and traditional knowledge. -

Diversity and Community Composition of Vertebrates in Desert River Habitats

RESEARCH ARTICLE Diversity and Community Composition of Vertebrates in Desert River Habitats C. L. Free1*, G. S. Baxter2, C. R. Dickman3, A. Lisle2, L. K.-P. Leung1 1 School of Agriculture and Food Sciences, University of Queensland, Gatton, Queensland 4343, Australia, 2 School of Geography, Planning and Environmental Management, University of Queensland, St Lucia, Queensland 4072, Australia, 3 Desert Ecology Research Group, School of Biological Sciences, University of Sydney, Sydney, New South Wales 2006, Australia * [email protected] Abstract Animal species are seldom distributed evenly at either local or larger spatial scales, and instead tend to aggregate in sites that meet their resource requirements and maximise fit- a11111 ness. This tendency is likely to be especially marked in arid regions where species could be expected to concentrate at resource-rich oases. In this study, we first test the hypothesis that productive riparian sites in arid Australia support higher vertebrate diversity than other desert habitats, and then elucidate the habitats selected by different species. We addressed the first aim by examining the diversity and composition of vertebrate assemblages inhabit- ing the Field River and adjacent sand dunes in the Simpson Desert, western Queensland, OPEN ACCESS over a period of two and a half years. The second aim was addressed by examining species Citation: Free CL, Baxter GS, Dickman CR, Lisle A, composition in riparian and sand dune habitats in dry and wet years. Vertebrate species Leung LK-P (2015) Diversity and Community Composition of Vertebrates in Desert River Habitats. richness was estimated to be highest (54 species) in the riverine habitats and lowest on the PLoS ONE 10(12): e0144258.