Fact Page 11-12 Healthy Prison Summary Hp.01-Hp.46 13-22

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Matter of Conviction Rachel O'brien and Jack Robson

A Matter of Conviction A blueprint for community-based rehabilitative prisons Rachel O’Brien and Jack Robson October 2016 The mission of the RSA (Royal Society for the encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce) is to enrich society through ideas and action. We believe that all human beings have creative capacities that, when understood and supported, can be mobilised to deliver a 21st century enlightenment. We work to bring about the conditions for this change, not just amongst our diverse Fellowship, but also in institutions and communities. By sharing powerful ideas and carrying out cutting- edge research, we build networks and opportunities for people to collaborate, creating fulfilling lives and a flourishing society. Transition Spaces is a community interest company set up in 2015 to work with justice services to strengthen rehabilitative outcomes. Its focus is on co-design – incubating and facilitating practical change with staff and service users – and on bridging the gap between theory, evidence and practice. For further information please visit: www.thersa.org/action- and-research/ rsa-projects/public-services-and-communities-folder/ future-prison. Or contact Jack: [email protected] Contents About Us 5 Foreword 7 Acknowledgements 9 Key Points 13 SECTION 1: THE CASE FOR CHANGE 1. From Object to Citizens 19 2. Reducing Risk through Strengthening Rehabilitation 29 SECTION 2: THE CONTEXT OF CHANGE 3. Where We Are Now 41 4. Justice Reform 49 5. Health and Wellbeing 57 6. A Time for Transformation 65 SECTION 3: A BLUEPRINT FOR COMMUNITY-BASED REHABILITATIVE PRISONS 7. A New Model of Accountability 73 8. -

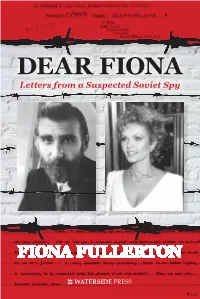

Dear Fiona: Letters from a Suspected Soviet

In this poignant and revealing memoir, Fiona DEAR FIONA FIONA DEAR Fullerton tells for the first time the story of Letters from a Suspected Soviet Spy her friendship with Alex Alexandrowicz a category-A high security prisoner who was He was a suspected Cold War spy. to serve 22 years for a crime he didn’t com- mit. Based on their original letters to each She was a KGB double agent in a Bond movie. other, the narrative is one of startling con- trasts — the darkness of a man incarcerated When a prisoner writes to a movie star, the best DEAR FIONA and a woman surrounded by the brightest he can hope for is a signed photo. But when lights of show business. Alex Alexandrowicz wrote to glamorous actress Letters from a Suspected Soviet Spy Fiona Fullerton, he didn’t expect it to lead to a “It is you alone who has given me strength while friendship spanning 30 years. I have been in prison, the strength to restore lost and dying hope into burning resolution”. Fiona Fullerton was for 30 years a leading The book uncovers Alex’s tender poetry, FIONA FULLERTON actress in theatre, television and films. She prison diaries and artwork, often produced is now a property guru, journalist, interior in solitary confinement while Fiona shares designer and author of three books about her doubts about the fragility of celebrity. investing in the property market. She lives in the Cotswolds with her husband and two “Have you ever heard of Nadejda Philaretovna children. von Meck? She and Tchaikovsky were corre- sponding for years, they never met — and yet he produced his finest work for her. -

NWD Resource

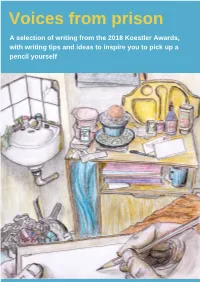

Voices from prison A selection of writing from the 2018 Koestler Awards, with writing tips and ideas to inspire you to pick up a pencil yourself This resource gives a taste of some of the thoughtful, inventive and moving writing produced by entrants to the 2018 Koestler Awards. We’ve pulled out some of our favourite written entries, a fraction of the nearly 2,000 that came in last year. They give an idea of the vast range of approaches and ideas sent to us, and we hope they will inspire you to try new things! Characters can bring your writing to life, drawing in your People readers and giving a voice to your narrative. Have a look at these very different approaches to describing two people. Funny Business (extract) HM Prison Isle of Wight, Parkhurst The brothers bore a family resemblance but not judged by their looks; they had the same facial expressions, body language, even patterns of speech – as if somebody had duplicated the same person in the bodies of two strangers. Jacky (otherwise Jackson – don’t ask) was tall with dark thinning hair, as lean as a broom handle and had that rumpled look that you’d get by sleeping in your clothes. Johnny (otherwise Johnson – again, don’t ask) was short, paunchy with a Bela Lugosi [Dracula] hairstyle, totally inappropriate considering he was ashen blond. His rumpled look was of a sort that appeared other people had been sleeping in the clothes with him. These were my dinner companions, the Longstreet brothers… She And I (extract) Shaftesbury Clinic I like coffee, she likes tea Her favourite cake is banoffee where mine is cheese She likes to party when I want to chill I think riding should be easy but she likes struggling uphill I’m fond of jackets. -

ART by OFFENDERS, SECURE PATIENTS and DETAINEES from the 2015 KOESTLER AWARDS Welcome Koestler Awards

ART BY OFFENDERS, SECURE PATIENTS AND DETAINEES FROM THE 2015 KOESTLER AWARDS Welcome Koestler Awards ‘I am very proud to be part of the RE:FORM All the work in RE:FORM was selected from 8,509 exhibition and hope that visitors will see entries to the 2015 Koestler Awards. The annual that positive things can come from prisons.’ Koestler Awards were founded in 1962 by the writer Exhibited artist Arthur Koestler and newspaper proprietor David Astor. Koestler (1905 – 1983) was a political prisoner RE:FORM is the UK’s annual national showcase and wrote the classic prison novel Darkness at Noon. of arts by prisoners, offenders on community Contributions come from prisons, secure hospitals, sentences, secure psychiatric patients and young offender institutions, secure children’s immigration detainees. It is the eighth exhibition homes and immigration removal centres, as well as in an ongoing partnership between the Koestler from people on community service orders and on Trust and Southbank Centre. probation in the community. Entries are also received from British prisoners overseas through a partnership This year’s show was curated by the Southbank with the charity Prisoners Abroad. Centre and the Koestler Trust to showcase many of the pieces chosen for Koestler Awards by over Entrants can submit artworks across 61 different 100 arts professionals (including Jeremy Deller, categories of fine and applied arts, design, music, Alan Kane, Carol Ann Duffy, the BFI and writing, film and animation. The artworks are judged Hot Chip) and the breadth of talent and creativity by professionals in each field. This year’s judges of people within the criminal justice system. -

K OESTLER Trustarts Mentoring for Ex-Offenders

1 KOESTLER TRUST Arts Mentoring for Ex-Offenders (Cover image) Another Face in the Crowd? Mixed Media entry 2012 Sean HM Prison Oakwood, Wolverhampton 12K6219 2 3 CONTENTS Introduction ...................................................................................5 Mentee - Why I applied to be mentored ........................................9 What I got out of mentor training .................................................13 The application process: probation referral ..................................17 Vasiliki Mentor Profile .................................................................18 When I found out I had been matched with a mentor ...................23 Mentor matching: The first meeting ..............................................27 Monument trust scholarship award for fine art 2010 ...................32 The Stephen and Winifred Tumim memorial scholarship award ..34 Evelyn Plesch scholarship award for painting ..............................35 Monument trust scholarship award for fine art 2013 ....................36 Chris Bramble scholarship award for ceramics ............................37 My reason for getting involved with Koestler ...............................41 mentor: Looking back on the mentoring .......................................48 Mentee: What I have gone on to do ..............................................50 Funder .........................................................................................52 With Thanks ...............................................................................53 -

October 2016 / Issue No

“I realised my not wanting to Black History be on TV was just insecurity and with issues of freedom Month and liberty at stake that seemed a pretty poor excuse Cops, Slaves not to try and help” and Usain Bolt Louise Shorter Comment // page 19 To celebrate this special I feel uneasy and once again the National Newspaper for Prisoners & Detainees month Inside Time reveals “ the powerlessness of my a voice for prisoners since 1990 some startling facts about situation crushes me.” the West Indies Kelly Wober October 2016 / Issue No. 208 / www.insidetime.org / A ‘not for profit’ publication / ISSN 1743-7342 An average of 60,000 copies distributed monthly Independently verified by the Audit Bureau of Circulations Usain Bolt: fastest man in the world Comment // page 32 Comment // page 21 We are ‘Shambolic!’ all human This year the annual Prison reform agenda or no prison reform Koestler Exhibition at London’s South Bank agenda? Shadow Justice Minister Jo Stevens Centre is curated by ‘disappointed’ by Justice Secretary Liz Truss’s multi-award winning poet Benjamin performance in front of the Justice Select Zephaniah. He tells Committee, she tells Inside Time Inside Time why he was initially reluctant Erwin James “Brandi” Bronze and what he thinks of 30 Award for sculpture the 2016 exhibits In her first appearance before the Justice Select Committee last month since taking over the role from Michael Gove in July, Justice Secretary Liz Truss Extreme measures cast a shadow of uncertainty over the government’s much “Those who are intent on trying to convert others to violent heralded prison reform agen- da. -

The Social Impact of Solvent Abuse, and Much Less Is Understood About the Financial Costs of That Impact to Individuals, Their Families, and to Wider Society

The Social Impact of Solvent Abuse December 2017 Image credit: The Dream Door is Too Small Carla Ross Senior Researcher, BWB Advisory & Impact 020 7551 7862 [email protected] Louise Barker Analyst, BWB Advisory & Impact 020 7551 7728 [email protected] Contents Executive summary 2 Introduction 10 Background on Re-Solv 12 Section 1: How people fall into solvent abuse 13 Section 2: Social & financial costs of solvent abuse 33 Profile 1: Young & experimental users 41 Profile 2: Young & regular users 44 Profile 3: Adult & high functioning users 47 Profile 4: Unstable lives 50 Profile 5: Chronic solvent users 54 Profile 6: Chronic poly-drug users 58 Cost to Government Services 61 Sensitivity Test 68 Section 3: Themes & recommendations for reducing the impact of solvent abuse 71 Appendices 83 Appendix A: Methodology 84 Appendix B: Sensitivity Test Explanation 86 Appendix C: Re-Solv’s Theory of Change 92 The images used in this report This report is illustrated with artwork entered into the Koestler Trust’s annual award scheme. The images were created by people in prison, on probation, and in other secure settings. The Koestler Trust is the UK’s best-known prison arts charity. It encourages prisoners to change their lives through taking part in the arts, and aims to challenge negative preconceptions of what those in prison are capable of achieving. Many of the artworks show how it feels to live with the problems frequently raised in this research, such as poor mental health, the impact of substance use, and the experience of imprisonment. The images bring to life raw experiences that can get lost and become more sanitised in reports such as this one. -

2019 Koestler Awards Results (At 28.08.19)

2019 Koestler Awards Results (at 28.08.19) . This is the final list of entries which have won awards. If an entry is not listed, it probably did not win an award. We are open all year round to entries from under 18s and will respond to these with feedback and certificates within 6 weeks. Your package must be marked “Under 18s Fast Feedback Programme”. In most artforms, the awards given are as follows: Platinum £100 + certificate Gold £60 + certificate Silver £40 + certificate Bronze £20 + certificate Special Award for Under 18s / Under 25s £25 + certificate First-time Entrant £25 + certificate Highly Commended Certificate Commended Certificate Some awards are generously sponsored and named by Koestler Trust supporters. Every entrant will receive a Participation Certificate, and most will receive written feedback. Certificates, feedback and prize cheques for entrants will be sent by the end of October 2019. “K No” is the Koestler reference number that we allocate to each artwork. Please have this number and your entry details to hand if you have an enquiry about a particular entry. More information from [email protected] or 020 8740 0333. We cannot give out information to third parties. Entrants are not named, but this list shows where entrants have originally entered from – not where they are now. Around 180 examples of visual art, audio, film and writing, have been selected for our annual UK exhibition. This is open to the public from 19 Sept – 03 Nov daily at London’s Southbank Centre. The opening event is on Wednesday 18 Sept from 2pm; all are welcome. -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Health and Wellbeing Board, 20/05

AGENDA HEALTH AND WELLBEING BOARD Wednesday, 20th May, 2015, at 6.30 pm Ask for: Ann Hunter Darent Room, Sessions House, County Hall, Telephone 03000 416287 Maidstone Refreshments will be available 15 minutes before the start of the meeting Membership Mr R W Gough (Chairman), Dr F Armstrong, Mr I Ayres, Dr B Bowes (Vice-Chairman), Mr A Bowles, Ms H Carpenter, Mr P B Carter, CBE, Mr A Scott-Clark, Dr D Cocker, Ms P Davies, Mr G K Gibbens, Mr S Inett, Mr A Ireland, Dr M Jones, Dr E Lunt, Dr N Kumta, Dr T Martin, Mr P J Oakford, Mr S Perks, Dr R Stewart, Ms D Tomalin, Cllr P Watkins and Cllr L Weatherly UNRESTRICTED ITEMS (During these items the meeting is likely to be open to the public) 1 Chairman's Welcome 2 Apologies and Substitutes To receive apologies for absence and notification of any substitutes 3 Declarations of Interest by Members in Items on the Agenda for this Meeting To receive any declarations made by members of the board relating to items on the agenda 4 Minutes of the Meeting held on 18 March 2015 (Pages 5 - 12) To agree the minutes of the meeting held on 18 March 2015 5 Workforce (Pages 13 - 30) To consider issues relating to the health and care workforce required to deliver the Five Year Forward View and the broader changes needed to establish a sustainable health and care sector across Kent 6 Kent and Medway Growth and Infrastructure Framework (Pages 31 - 36) To note the progress being made to establish a Growth and Infrastructure Framework for Kent and Medway and provide comment on how best to engage with the health -

2019 Koestler Awards Results (At 28.08.19)

2019 Koestler Awards Results (at 28.08.19) . This is the final list of entries which have won awards. If an entry is not listed, it probably did not win an award. We are open all year round to entries from under 18s and will respond to these with feedback and certificates within 6 weeks. Your package must be marked “Under 18s Fast Feedback Programme”. In most artforms, the awards given are as follows: Platinum £100 + certificate Gold £60 + certificate Silver £40 + certificate Bronze £20 + certificate Special Award for Under 18s / Under 25s £25 + certificate First-time Entrant £25 + certificate Highly Commended Certificate Commended Certificate Some awards are generously sponsored and named by Koestler Trust supporters. Every entrant will receive a Participation Certificate, and most will receive written feedback. Certificates, feedback and prize cheques for entrants will be sent by the end of October 2019. “K No” is the Koestler reference number that we allocate to each artwork. Please have this number and your entry details to hand if you have an enquiry about a particular entry. More information from [email protected] or 020 8740 0333. We cannot give out information to third parties. Entrants are not named, but this list shows where entrants have originally entered from – not where they are now. Around 180 examples of visual art, audio, film and writing, have been selected for our annual UK exhibition. This is open to the public from 19 Sept – 03 Nov daily at London’s Southbank Centre. The opening event is on Wednesday 18 Sept from 2pm; all are welcome. -

October 2018 / Issue No

“Art for communicating “Free or imprisoned, “When I was in prison...” and rebuilding relation- emotional, informative Benjamin Zephaniah the National Newspaper for Prisoners & Detainees ships is prevalent in this stories have the same tells Rachel Billington exhibition” Clare Barstow effect” Steve Newark how poetry ‘made’ his life a voice for prisoners since Inside Art // page 27 Comment // page 17 Inside Poetry October 2018 / Issue No. 232 / www.insidetime.org / A ‘not for profit’ publication / ISSN 1743-7342 INSIDE POETRY and CHANGING LIVES TOGETHER supplements inside 68 PAGE ISSUE An average of 60,000 copies distributed monthly Independently verified by the Audit Bureau of Circulations PRISONS CHIEF ‘Enough is enough’ Prisons Inspector issues Urgent Notification for HMP Bedford Inside Time report through suicide. We have seen consistent warnings about overcrowding and violence, STEPS DOWN a shocking riot, the creation of a performance As the fourth Urgent Notification Protocol in improvement plan and the imposition of spe- After nine years in charge of Prisons and 12 months was issued by the Chief Inspector cial measures - and none of these drastic of Prisons prison reform group the Howard events has prompted decisive action to turn Probation, Michael Spurr CB ‘has been asked to League calls for bold action to be taken. An- the prison around. Particularly concerning drew Neilson, the Howard League’s Director is what this sustained failure says about the stand down’ by Justice Secretary David Gauke of Campaigns said: “This damning verdict prison system as a whole. Enough is enough. on Bedford prison has not come out of no- More jails will fail and many more people Inside Time report North and East Anglia and where; as the Chief Inspector says, this is a will be hurt unless we see bold action to re- then, following a restructur- story of inexorable and unchecked decline. -

BLÜCHER Commercial References

BLÜCHER Commercial References Country Name City Year Segment SubSegment Products BLÜCHER Channel Argentina Hotel Arakur Ushuaia 2011 Commercial Hotel BLÜCHER Drain Design Australia Hawkesbury Districct Windsor, NSW Commercial Hospital Australia Robina Hospital Gold Coast, QLD 2009 Commercial Hospital BLÜCHER EuroPipe Department of Defence – HNA BLÜCHER Drain Design Australia Murray Bridge Murray Bridge, WA 2011 Commercial Public building BLÜCHER EuroPipe Equine Health and Performance Educational Australia Centre Adelaide, WA 2011 Commercial establishment BLÜCHER Drain Design K9 Facility – Australian Federal Australia Police WA 2012 Commercial Prison BLÜCHER Drain Design Australia Port Augusta Prison Adelaide, WA 2012 Commercial Prison BLÜCHER EuroPipe Australia Geelong Hospital Geelong, VIC 2013 Commercial Hospital BLÜCHER EuroPipe Hunter Medical Research New Lambton Heights Australia Institute , NSW 2013 Commercial Hospital BLÜCHER EuroPipe Australia San Hospital Wahroonga, NSW 2013 Commercial Hospital Australia Woolworths NSW 2013 Commercial Supermarket BLÜCHER Drain Design Adelaide University, Badger Educational Australia Building Adelaide, SA Commercial establishment Australia Adventist Wahroonga Sydney, NSW Commercial Hospital Australia Ainslie Football Club Canberra, ACT Commercial Leisure Australia Albury Albury, NSW Commercial Hospital Australia Alice Springs Jail Alice Springs, NT Commercial Prison Australia AMCWC Adelaide, SA Commercial Hospital Australia Aquatic Centre Hobart, TAS Commercial Leisure Australia Austin Melbourne,