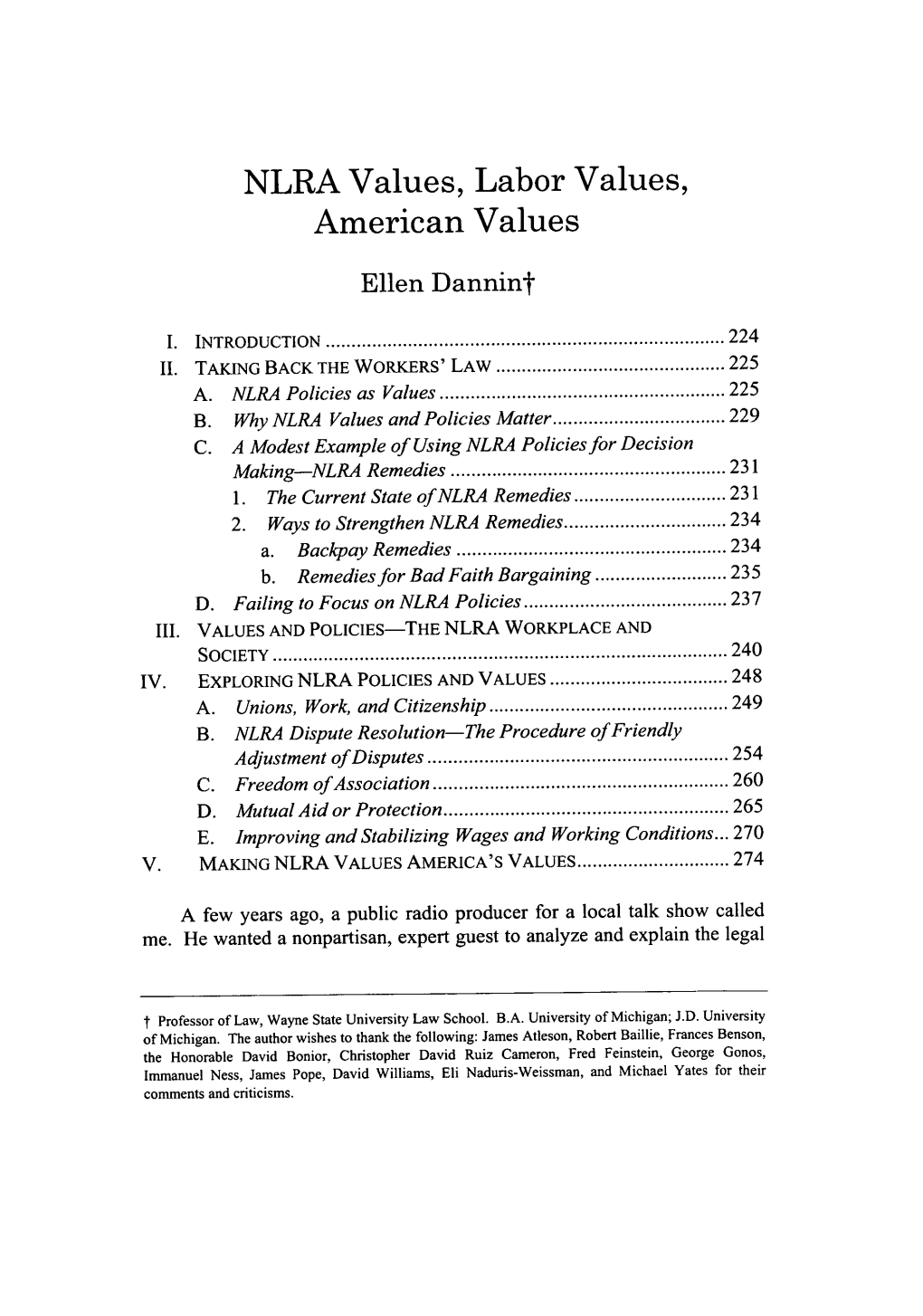

NLRA Values, Labor Values, American Values

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fannie Weiss Distinguished Faculty Scholar And

ELLEN DANNIN Fannie Weiss Distinguished Faculty Scholar and Professor of Law Pennsylvania State University Dickinson School of Law Lewis Katz Building University Park, PA 16802-1912 814 865-8996 fax - 814 863-7274 [email protected] ___________________________________________________ ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY - DICKINSON SCHOOL OF LAW, University Park, Pennsylvania Professor of Law, 2006-Present Courses taught: Labor Law, Employment Law, Civil Procedure WAYNE STATE UNIVERSITY LAW SCHOOL, Detroit, Michigan Professor of Law, 2002 - 2006 Courses taught: Labor Law, Employment Law, Civil Procedure, Labor Law Seminar UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN LAW SCHOOL, Ann Arbor, Michigan Visiting Professor of Law, Winter 2002 Courses taught: Labor Law, Seminar: Immigrants, Work and Justice UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS, AMHERST, M.S. Program in Union Leadership and Administration Visiting Professor, 1999-2002 Course taught: Labor Law CALIFORNIA WESTERN SCHOOL OF LAW, San Diego, California Professor of Law, 1995-2002 Associate Professor of Law, 1991-1995 Courses taught: Labor Law, Employment Law, Civil Procedure, Labor Seminars, Employment Discrimination and Benefits, Public Sector Labor Law, Evidence VICTORIA UNIVERSITY, WELLINGTON, LAW DEPARTMENT, Wellington, New Zealand Scholar in Residence, 1997 Scholar in Residence, 1994 VICTORIA UNIVERSITY, WELLINGTON, CENTRE FOR INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS, Wellington, New Zealand Scholar in Residence, 1992 WAIKATO UNIVERSITY, FACULTY OF MANAGEMENT, Hamilton, New Zealand Scholar in Residence, 1996 OTAGO UNIVERSITY, -

Solidarity Forever? Unions and Bargaining Representation Under New Zealand's Employment Contracts Act

Loyola of Los Angeles International and Comparative Law Review Volume 18 Number 1 Article 1 12-1-1995 Solidarity Forever? Unions and Bargaining Representation under New Zealand's Employment Contracts Act Ellen Dannin Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/ilr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Ellen Dannin, Solidarity Forever? Unions and Bargaining Representation under New Zealand's Employment Contracts Act, 18 Loy. L.A. Int'l & Comp. L. Rev. 1 (1995). Available at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/ilr/vol18/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola of Los Angeles International and Comparative Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LOYOLA OF LOS ANGELES INTERNATIONAL AND COMPARATIVE LAW JOURNAL VOLUME 18 DECEMBER 1995 NUMBER 1 Solidarity Forever? Unions and Bargaining Representation Under New Zealand's Employment Contracts Act ELLEN DANNIN* I. Introduction .............................. 2 II. Bargaining Representation and the ECA: Some Initial Considerations ............................ 3 III. Basics of Representation Under the ECA ......... 12 A. Employer Opposition to Union Authorization 14 1. Treatment of Bargaining Representatives 14 2. Union Access to Employees ............ 17 3. Union Party Status ................... 20 4. Withdrawal of Authorizations ........... 22 B. Bargaining with Authorized Representatives ... 33 1. Direct Dealing ....................... 38 2. Dealing with Nonauthorized Representatives 44 3. Pressure to Revoke Authorizations ....... 46 C. Representation Authority as a Procedural Hurdle 52 1. -

Finding the Workers'

Finding the Workers’ Law Ellen Dannin FEW YEARS AGO, a local public official. Today, most people may regard any radio producer called. He wanted business representative as neutral and reli- a nonpartisan, expert guest to able, while unions are partisan and a special analyze issues involved in a strike for a talk interest. If correct, this explains why the Ashow. I answered his questions about collec- National Labor Relations Act (NLRA), the tive bargaining and strikes with basic labor National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), and law: an employer must bargain with a union; unions are popularly regarded as irrelevant the law protects employees’ right to strike for and even un-American. If true, this experi- higher wages; and an employer violates the ence may capture some reasons why union law if it fires them for striking. membership is declining. I was not surprised that the producer did not call back, for I could sense that to him my Of What Use Are Unions? explanation of black letter labor law seemed so radical, it could not be true. Instead, the Certainly, union membership is not declin- show’s sole guest was the struck company’s ing because they have no work to do. Unions human resources director. still help bring the poor out of poverty. I suspect that few in the audience thought Unionized workers make from $4,000 to it odd to hear the views of only one party to $0,000 more a year than unorganized work- a dispute when that person was a company ers doing the same work.¹ Unionized work- Ellen Dannin is a professor of law at Wayne State University Law School. -

Legislative Intent and Impasse Resolution Under the National Labor Relations Act: Does Law Matter? Ellen J

Hofstra Labor and Employment Law Journal Volume 15 | Issue 1 Article 2 1997 Legislative Intent and Impasse Resolution Under the National Labor Relations Act: Does Law Matter? Ellen J. Dannin Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/hlelj Recommended Citation Dannin, Ellen J. (1997) "Legislative Intent and Impasse Resolution Under the National Labor Relations Act: Does Law Matter?," Hofstra Labor and Employment Law Journal: Vol. 15: Iss. 1, Article 2. Available at: http://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/hlelj/vol15/iss1/2 This document is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hofstra Labor and Employment Law Journal by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dannin: Legislative Intent and Impasse Resolution Under the National Labo ARTICLES LEGISLATIVE INTENT AND IMPASSE RESOLUTION UNDER THE NATIONAL LABOR RELATIONS ACT: DOES LAW MATTER? Ellen J. Dannin* "Impasse and implementation is the dominant consideration of virtually every negotiation" that he has been involved in, said Samuel McKnight, a union attorney .... "It is a prospect that is so attractive to employers and so menacing to unions and workers that we don't really like to talk about it." The possibility of impasse implementation has reduced the lan- guage of collective bargaining to "a list of words and phrases that unions can never use and employers must always use," such as "deadlock," "bottom line," "best offer," and 'final offer," said McKnight.' * Professor of Law, California Western School of Law, San Diego, California. -

21 Taking Back the Worker S

-raking Back theWorkers' Law HOW TO FIGHT THE ASSAULT ON LABOR RIGHTS ELLEN DANNIN ILR PRESS an imprint of CORNELL UNIVERSITY PRESS ITHACA AND LONDON CO.,.E.,.S MARTIN. P. CA q'l;.R, .!t"}.J yrQy l'i~':i ';./11\\ I'Li [OI'1 I n nDU " .i"'" '/'\I S I !H~J. i..f\uUd rj~iJI i 11.11'1.S .C',om€N1 Universi1\' Copyright @ 2006 by Cornell University All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher. For information, address Foreword by David E. Bonior Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New York 14850. Acknowledgments First published 2006 by Cornell University Press Introduction: Reviving the Labor Mov Printed in the United States of America 1 Why Judges Rewrite Labor Law Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Pllblication Data 2 Developing a Strategy to Take Back thl Dannin, Ellen J. NLRA Values, American Values Taking back the workers' law: how to fight the assault on labor rights 3 I Ellen Dannin Litigating the NLRA Values-What) p. cm. 4 Includes bibliographical references and index. 5 Litigation Themes ISBN-13: 978-0-8014-4438-8 (cloth: alk. paper) ISBN-lO: 0-8014-4438-1 (cloth: alk. paper) 6 NLRA Rights within Other Laws 1. Labor laws and legislation-United States. 2. Employee rights -United States. 3. United States. National Labor Relations Act. 7 Trying Cases- The Rules 4. Industrial relations-United States. 1. Title. -

Than Just a Cool T-Shirt: What We Don't Know About Collective Bargaining-But Should-To Make Organizing Effective Ellen Dannin

Hofstra Labor and Employment Law Journal Volume 25 | Issue 1 Article 4 2007 More Than Just A Cool T-Shirt: What We Don't Know About Collective Bargaining-But Should-To Make Organizing Effective Ellen Dannin Gangaram Singh Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/hlelj Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Dannin, Ellen and Singh, Gangaram (2007) "More Than Just A Cool T-Shirt: What We Don't Know About Collective Bargaining-But Should-To Make Organizing Effective," Hofstra Labor and Employment Law Journal: Vol. 25: Iss. 1, Article 4. Available at: http://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/hlelj/vol25/iss1/4 This document is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hofstra Labor and Employment Law Journal by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dannin and Singh: More Than Just A Cool T-Shirt: What We Don't Know About Collectiv MORE THAN JUST A COOL T-SHIRT: WHAT WE DON'T KNOW ABOUT COLLECTIVE BARGAINING-BUT SHOULD-TO MAKE ORGANIZING EFFECTIVE Ellen Dannin*& GangaramSingh ** ABSTRACT Union organizing is much in the news these days as legislation to facilitate unionization wends its way through Congress.1 However, it takes more than organizing to organize unions and to maintain organization. Workers do not join unions just to be members or to get cool t-shirts and sing "Solidarity Forever." Workers join unions because they want what unions can get them-better pay, just cause employment, respect, and a say in workplace conditions.2 Organizing alone cannot get these things. -

7Orkshop #Urrent

7ORKSHOP$ #URRENT,ABOR2ELATIONS)SSUESIN(IGHER%DUCATION 7ILLIAM!(ERBERT %SQ 0ANEL#HAIR $ISTINGUISHED,ECTURER (UNTER#OLLEGE %XECUTIVE$IRECTOR .ATIONAL#ENTERFORTHE3TUDYOF#OLLECTIVE"ARGAININGIN(IGHER%DUCATION .9# -AIREAD%#ONNOR %SQ ,AW/FFICESOF-AIREAD%#ONNOR 0,,# 3YRACUSE 0ETER$#ONRAD %SQ 0ROSKAUER2OSE,,0 .9# University Petitions Filed/Election Results1 1. CASES PENDING AT THE REGIONAL OFFICE LEVEL A. NOT BEING PROCESSED BY THE NLRB CORNELL UNIVERSITY Private Election Procedure Negotiated by Parties Case Status: Open On March 6, 2017, Graduate Students United, CGSU-AFT notified Cornell of its intent to file a petition. An election was held by manual ballot on March 27 and 28. As of March 29, the second of two days of voting, the ballot count was inconclusive: 856 votes in favor of the Union, 919 votes against representation, and 81 challenged ballots. The Union’s remains unresolved. Since the election, CGSU and the University have been in negotiations for a new agreement that would establish ground rules in that the Union wishes to proceed to a new election. CGSU recently presented the possibility of a new election to its membership in a referendum with three options: file objections to the original election with the arbitrator, agree to language amending the election agreement, or accept the results of the election hled last Spring. Voting on the referendum began on October 16, 2017. A decision by CGSU on how it will proceed is anticipated in January 2018. B. BEING PROCESSED BY THE NLRB UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA Case No. 04-RC-199609 Case Status: Open GET-UP UPenn filed a petition on May 30, 2017. -

Teaching Labor Law Within a Socioeconomic Framework Ellen Dannin

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of San Diego San Diego Law Review Volume 41 | Issue 1 Article 8 2-1-2004 Teaching Labor Law Within a Socioeconomic Framework Ellen Dannin Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.sandiego.edu/sdlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Ellen Dannin, Teaching Labor Law Within a Socioeconomic Framework, 41 San Diego L. Rev. 93 (2004). Available at: https://digital.sandiego.edu/sdlr/vol41/iss1/8 This Symposium Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital USD. It has been accepted for inclusion in San Diego Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital USD. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DANNIN.DOC 9/17/2019 3:57 PM Teaching Labor Law Within a Socioeconomic Framework ELLEN DANNIN* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................... 93 II. BACKGROUND ON LABOR LAW ............................................................................ 94 III. TEACHING LABOR LAW THROUGH A SOCIOECONOMIC LENS ................................ 95 A. Creating a Context ..................................................................................... 96 B. The Toothpaste Tube Theory of Labor Law ............................................... 98 C. Teaching the Case .................................................................................... 103 IV. CONCLUSION .................................................................................................... -

Dickinson Lawyer

WINTER The 2007 DICKINSON LAWYER REVIVING THE LABOR MOVEMENT A LETTER FROM THE DEAN MANAGING EDITOR he Dickinson School of Law kicked off 2007 with a number of exciting developments. Kelly R. Jones First and foremost, we were delighted to announce the two largest contributions in the history of the Law School: a $15 million gift from philanthropist Lewis Katz ’66, EDITOR founder of Katz, Ettin & Levine and former owner of the New Jersey Nets basketball Pam Knowlton Tfranchise, and a $4 million pledge from H. Laddie Montague Jr. ’63, managing principal of Berger CONTRIBUTORS & Montague, P.C. (See page 14 for full story.) Mr. Katz’s and Mr. Montague’s efforts and contribu- Mark Podvia tions on behalf of The Dickinson School of Law during the past few years have been extraordinary, Ed Savage Dyanna Stupar almost beyond description. A special issue of The Dickinson Lawyer, that we will publish in the next few weeks, will feature their efforts and contributions, and those of other DSL alumni, to our PHOTOS Carlisle Building Campaign. The University expressed its deep appreciation to Mr. Katz and Mr. Rick Bielaczyc Ian Bradshaw Photography Montague when the Penn State Board of Trustees voted unanimously on January 19, 2007, to Kelly R. Jones name the new signature additions to the Law School’s Carlisle facilities Dyanna Stupar Lewis Katz Hall; the Law School’s new building in University Park the Lewis Katz Building; and the Law School’s unified library the H. Lad- ILLUSTRATIONS James Yang die Montague Jr. Law Library. These generous donations, donations from other generous Law TECHNICAL SUPPORT School alumni and friends, $10 million from the University, and $25 Dian Franko million in matching funds from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania DESIGN have provided a $50 million budget for our Carlisle building project (as Claude Skelton well as a wonderfully significant increase in the Law School’s endow- ment). -

The National Labor Relations Act

Loyola of Los Angeles Law Review Volume 34 Number 1 The Seventh Annual Fritz B. Burns Lecture: The War Powers Resolution and Article 7 Kosovo 11-1-2000 Lawless Law—The Subversion of the National Labor Relations Act Ellen J. Daninn Terry H. Wagar Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/llr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Ellen J. Daninn & Terry H. Wagar, Lawless Law—The Subversion of the National Labor Relations Act, 34 Loy. L.A. L. Rev. 197 (2000). Available at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/llr/vol34/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola of Los Angeles Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LAWLESS LAW? THE SUBVERSION OF THE NATIONAL LABOR RELATIONS ACT Ellen J. Dannin & Tel-y H. Wagar'* I. INTRODUCTION Why is it that since the mid-1950s United States union density has declined from about 30% to its current level of 1 I% to 15%?' We know the decline has not affected all groups. Public sector union membership has risen while unionization in the private sector has plummeted: nearly 38% of government workers were union mem- * Professor of Law, California Western School of Law, San Diego, Cali- fornia. B.A., University of Michigan; J.D., University of Michigan. An earlier version of this paper was delivered at the 1999 Law and Society Association Annual Meeting in Chicago. -

More Than Just a Cool T-Shirt: What We Don’T Know About Collective Bargaining—But Should—To Make Organizing Effective

DANNIN 6.10.08 [FINAL PROOFREAD] 6/10/2008 3:53:43 PM MORE THAN JUST A COOL T-SHIRT: WHAT WE DON’T KNOW ABOUT COLLECTIVE BARGAINING—BUT SHOULD—TO MAKE ORGANIZING EFFECTIVE Ellen Dannin* & Gangaram Singh** ABSTRACT Union organizing is much in the news these days as legislation to facilitate unionization wends its way through Congress.1 However, it takes more than organizing to organize unions and to maintain organization. Workers do not join unions just to be members or to get cool t-shirts and sing “Solidarity Forever.” Workers join unions because they want what unions can get them—better pay, just cause employment, respect, and a say in workplace conditions.2 Organizing alone cannot get these things. Organizing is only a vehicle that leads to the collective bargaining power that wins workplace rights. As Samuel Gompers said in 1925, “[e]conomic betterment—today, tomorrow, in home and shop, was the foundation upon which trade unions have been buil[t].”3 Through collective bargaining, workers can earn more money, have greater job security, exercise greater control over * Fannie Weiss Distinguished Faculty Scholar and Professor of Law, Pennsylvania State University—Dickinson School of Law. B.A., University of Michigan; J.D., University of Michigan. ** Professor and Chair, Department of Management, College of Business Administration, San Diego State University. Ph.D., Industrial Relations, University of Toronto; M.I.R., Industrial Relations, University of Toronto; M.B.A., Business Administration, University of Toronto; B.Comm., Business Administration, University of Windsor. 1. See Employee Free Choice Act (EFCA), H.R. 800, 110th Cong. -

Taking Back the Workers' Law: How to Fight the Assault on Labor Rights 3 I Ellen Dannin Litigating the NLRA Values-What) P

Cornell University ILR School DigitalCommons@ILR Book Samples ILR Press January 2006 Taking Back the Workers’ Law: How to Fight the Assault on Labor Rights Ellen Dannin Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ilr.cornell.edu/books Thank you for downloading an article from DigitalCommons@ILR. Support this valuable resource today! This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the ILR Press at DigitalCommons@ILR. It has been accepted for inclusion in Book Samples by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@ILR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. If you have a disability and are having trouble accessing information on this website or need materials in an alternate format, contact [email protected] for assistance. Taking Back the Workers’ Law: How to Fight the Assault on Labor Rights Abstract [Excerpt] This book focuses on unions and on the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) and National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) – the agency and the law created to promote unionization and collective bargaining. This is not a story of mourning. Rather, this book advocates borrowing from and building on the methods the civil rights movement, and in particular, the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, used to recaptured union power. They teach us that a litigation and activist strategy can overturn unjust judicial decisions, even those by the Supreme Court. More recently, the National Right to Work Legal Defense Foundation is proving that a targeted litigation strategy can still be used to “amend” the law. Keywords United States, labor law, legislation, employee rights, industrial relations, National Labor Relations Board, NLRB, NLRA, NAACP, union, worker, fight, assault Comments The abstract, table of contents, and first twenty-five pages are published with permission from the Cornell University Press.