Editor's Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Characters

LIST OF CHARACTERS David Copperfield Agnes Wickfield The protagonist and narrator of the novel. David is David’s true love and daughter of Mr. Wickfield. The innocent, trusting, and naïve even though he suffers calm and gentle Agnes admires her father and David. abuse as a child. He is idealistic and impulsive and Agnes always comforts David with kind words or remains honest and loving. Though David’s troubled advice when he needs support. childhood renders him sympathetic, he is not perfect. He often exhibits chauvinistic attitudes toward the Mr Wickfield lower classes. In some instances, foolhardy decisions mar David’s good intentions. Mr. Wickfield is a lawyer and business manager for both Miss Betsey and Mrs Strong, David’s new headmaster. Mr Wickfield is a kind and generous man, Clara Copperfield but suffers from an alcohol addiction. This taste for David’s mother. The kind, generous, and goodhearted alcohol later becomes increasingly difficult to control, Clara embodies maternal caring until her death, which leaving Mr Dick and his clients vulnerable to the occurs early in the novel. David remembers his mother manipulation of others. as an angel whose independent spirit was destroyed by Mr. Murdstone’s cruelty. Mrs Strong The kind and straight talking headteacher of the Peggotty school in Canterbury that David later joins, arranged David’s nanny and caretaker. Peggotty is gentle and by his aunt and Mr Wickfield. selfless, opening herself and her family to David whenever he is in need. She is faithful to David and his James Steerforth family all her life, never abandoning David, his mother, or Miss Betsey. -

David Copperfield Charles Dickens

TEACHER GUIDE GRADES 9-12 COMPREHENSIVE CURRICULUM BASED LESSON PLANS David Copperfield Charles Dickens READ, WRITE, THINK, DISCUSS AND CONNECT David Copperfield Charles Dickens TEACHER GUIDE NOTE: The trade book edition of the novel used to prepare this guide is found in the Novel Units catalog and on the Novel Units website. Using other editions may have varied page references. Please note: We have assigned Interest Levels based on our knowledge of the themes and ideas of the books included in the Novel Units sets, however, please assess the appropriateness of this novel or trade book for the age level and maturity of your students prior to reading with them. You know your students best! ISBN 978-1-50203-727-5 Copyright infringement is a violation of Federal Law. © 2020 by Novel Units, Inc., St. Louis, MO. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or To order, contact your transmitted in any way or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, local school supply store, or: recording, or otherwise) without prior written permission from Novel Units, Inc. Toll-Free Fax: 877.716.7272 Reproduction of any part of this publication for an entire school or for a school Phone: 888.650.4224 system, by for-profit institutions and tutoring centers, or for commercial sale is 3901 Union Blvd., Suite 155 strictly prohibited. St. Louis, MO 63115 Novel Units is a registered trademark of Conn Education. [email protected] Printed in the United States of America. novelunits.com -

RALPH, NOGGS, FANNY, MRS. SQUEERS Pg 38-40 NOGGS. Yes Sir?

RALPH, NOGGS, FANNY, MRS. SQUEERS Pg 38-40 NOGGS. Yes sir? RALPH. Who called in my absence? NOGGS. A strange looking man. Kept whittling at his dirty fingernails with a knife. Didn’t like the looks of him. RALPH. What did he want? NOGGS. Didn’t say. RALPH. Did he leave a name? NOGGS. Not a syllable as to his identity. RALPH. Anyone else? NOGGS. MRS. SQUEERS and FANNY Squeers. RALPH. What do they want? NOGGS. Didn’t say. RALPH. Admit them. (NOGGS exits. RALPH rubs his chin and thinks.) Hmmmm. Most unusual for that pair to be in London. (MRS. SQUEERS enters. FANNY follows her.) RALPH. I trust you have not waited long. MRS. SQUEERS. We would have waited all week to bring you news of your wretched nephew. RALPH. What’s this? Nicholas? MRS. SQUEERS. You may call him Nicholas. We call him assassin! Bandit! Criminal! Baboon! (FANNY wails and collapses on the bench. She cries hysterically.) FANNY. He should be punished. MRS. SQUEERS. That boy broke poor Fanny’s heart. He led her on, always lurking about, pretending that his love for her was deep and sincere. (FANNY wails all the more.) When he had her loyalty and love, he cast her aside. Casanova! Brute! Okra! FANNY. He’s wicked! (She wails again.) RALPH. I’m astonished. MRS. SQUEERS. There is more! RALPH. Not of a like nature, I trust. MRS. SQUEERS. Worse! It is me, Mrs. Squeers, who must come to London for the new boys. Poor Squeery was beaten so badly by your nephew that he cannot stir from his bed. -

Literature CAT Two, 1999, Creative Response, David Copperf…

Literature CAT Two 97 152 172 L David Copperfield- Charles Dickens Creative Response. Statement of Intention: This creative piece is supposed to be additional chapter to Charles Dickens original manuscript of David Copperfield, I have aimed to write in a manner so it fits in seamlessly with the novel. This piece is an addition to be inserted after chapter 40, The Wanderer. I choose to write this piece as in reading the novel I became fascinated with both the bitter Rosa Dartle and eccentric Aunt Betsy Trotwood. In the novel David Copperfield, they never actually met so I have created a scene that will add to the tension and drama, when these two strong headed characters meet. Dickens frequently uses dialogue and the speech patterns of each character are very distinct and help him create give them personality and depth; for example Mr. Peggotty of the lower class uses words like, “bachelore1” instead of bachelor, “wureld2” instead of world, “nowt3” instead of nothing and “p’raps4” instead of perhaps, while Mr. Macawber another character whom Dickens want to show has pretensions, uses flamboyant language “remunerative5” instead of compensate and “infantine6” instead of endless. Therefore like Dickens, I have also used dialogue to capture both Rosa Dartle’s distinct speech patterns, either evasive or plain accusing and Aunt Betsy’s more abrupt and direct manner. David’s observant, innocent almost naïve and defenseless manner have also been maintain so that this piece is believable. I have recreated David’s manner of using long sentences with many commas in his observations. I have maintained David’s narration of the story, as the rest of the novel is written from David’s point of view. -

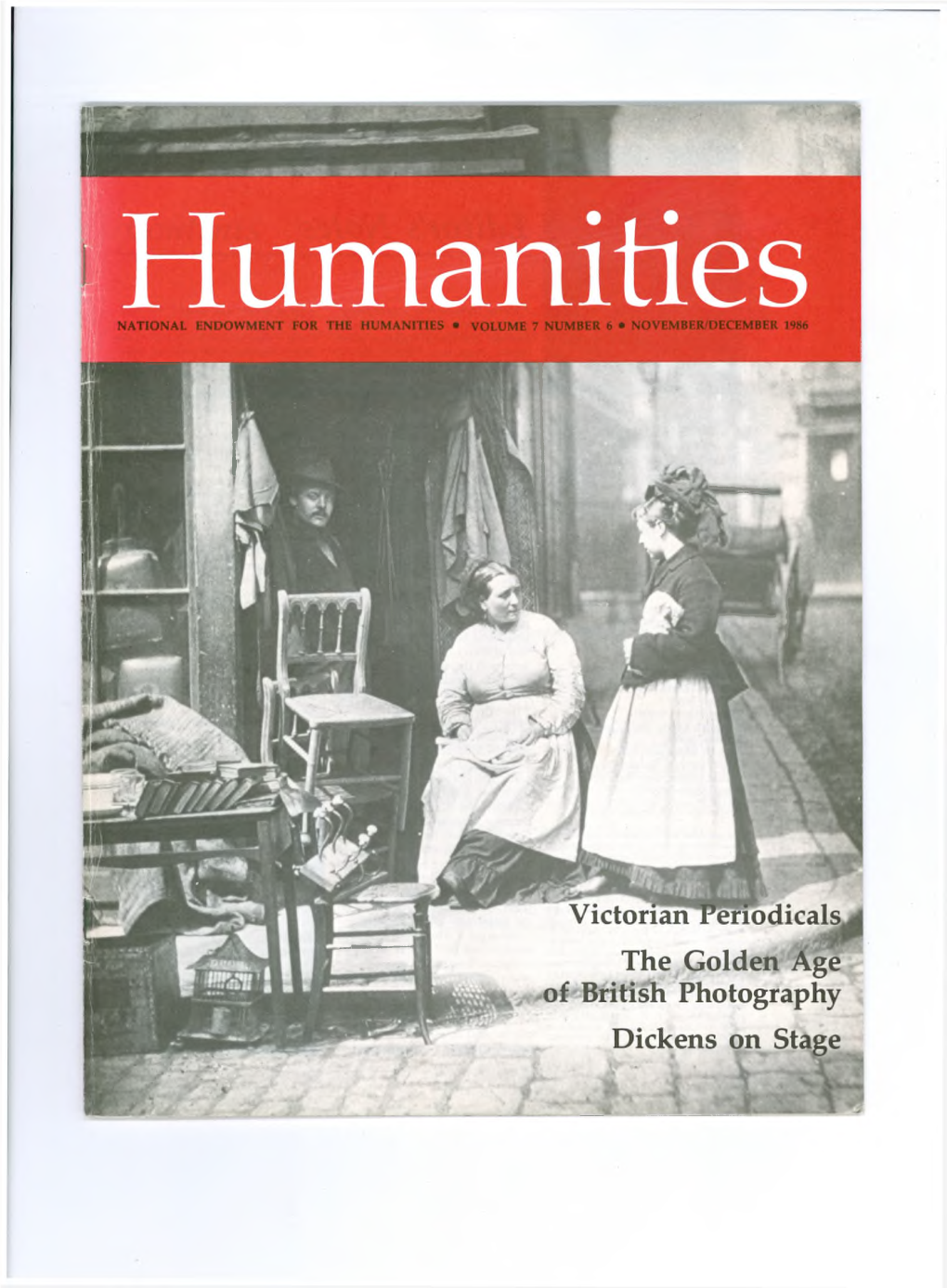

The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby

LOS ANGELES CITY COLLEGE NICHOLAS NICKLEBY, THE RECURRING PHENOMENON Los Angeles City College Theatre Academy by Fecicia Hardison Londre in association with Community Services presents It may be a measure of tile influence of Charles Dicken's his academy from infection. Although convicted of gross Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby that Brian Friel neglect (maggoty food and flea-infested beds among other nicknamed one of his characters in Translations 'The Infant offenses) and fined, Shaw continued to operate his school Phenomenon." H~NYJames, author of the novel on which The vividness with which Dickens painted social conditions The Innocents is based, saw a theatrical performance of in his day cannot alone explain the appeal of Nicholas Nicholas Nickleby (in his boyhood and, at 67, remembered it Nickleby for modern audiences, 145 years after the novel was THELIFE (3) vividly enough to write of it in his autobiography: "who written. His timeless, irresistible characterizations are a strong ADVENTURES OF shall deny the immense authority of the theatre, or that the point Although some critics object to his caricatures, Dickens stage is the mightiest of modern engines?" scarcely exaggerates in many of his embodiments of human Dickensalways longed to harness his talent to that mighti- failings, like Squeers, Noggs, and Mantalini. Santayana avers: est of modem engines,but wasnot successful in his occasional "There are such people; we are such people ourselves in our NICHOLAS NICKLEBY effortsasa playwright. Hisconsiderable influence on Victorian true moments, in our veritable impulses; but we are careful and later theatre came about through dramatizations by to stifle and hide those moments from ourselves and from the others of virtually all of his novels and many of his stories. -

Proto-Cinematic Narrative in Nineteenth-Century British Fiction

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Fall 12-2016 Moving Words/Motion Pictures: Proto-Cinematic Narrative In Nineteenth-Century British Fiction Kara Marie Manning University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons, and the Other Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Manning, Kara Marie, "Moving Words/Motion Pictures: Proto-Cinematic Narrative In Nineteenth-Century British Fiction" (2016). Dissertations. 906. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/906 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MOVING WORDS/MOTION PICTURES: PROTO-CINEMATIC NARRATIVE IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY BRITISH FICTION by Kara Marie Manning A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School and the Department of English at The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Approved: ________________________________________________ Dr. Eric L.Tribunella, Committee Chair Associate Professor, English ________________________________________________ Dr. Monika Gehlawat, Committee Member Associate Professor, English ________________________________________________ Dr. Phillip Gentile, Committee Member Assistant Professor, -

David Copperfield Author: Charles Dickens

Name: Mrs Chisty 6C Title– David Copperfield Author: Charles Dickens Background- The story follows the life of David Copperfield from childhood to maturity. David was born in Blunderstone, Suffolk, England, six months after the death of his father. David spends his early years in relative happiness with his loving, childish naive mother and their kind housekeeper, Mrs. Peggotty. The Setting- David Copperfield is begins in Blunderstone Rookery, a house in rural Suffolk. This home is an ideal setting in the years before his mother’s second marriage... After she marries Murdstone, it becomes a prison with Murdstone and his equally “firm" sister as they become Da- vid's keepers. The Plot- During David’s early childhood, his mother marries the violent Mr. Murdstone, who brings his strict sister, Miss Murdstone, into the house. The Murdstones treat David cruelly, and David bites Mr. Murdstone’s hand during one beating. The Murdstones send David away to school. Peggotty takes David to visit her family in Yarmouth, where David meets Pe- ggotty’s brother, Mr. Peggotty, and his two adopted children, Ham and Little Em’ly. Mr. Peggotty’s family lives in a boat turned upside down—a space they share with Mrs. Gummidge, the widowed wife of Mr. Peggotty’s brother. After this visit, David attends school at Salem House, which is run by a man named Mr. Creakle. David befriends and idolises an egotistical young man named James Steerforth. David also befriends Tommy Traddles, an unfortunate, corpulent young boy who is beat- en more than the others... Comments– An insight in to Victorian London through Dickens' pen has made a permanent mark on literature as one of the greatest books ever written. -

BBC 4 Listings for 5 – 11 January 2008 Page 1 of 3 SATURDAY 05 JANUARY 2008 Starting out on Their Careers

BBC 4 Listings for 5 – 11 January 2008 Page 1 of 3 SATURDAY 05 JANUARY 2008 starting out on their careers. Dr Nick Hollings has devoted half MON 21:00 Top of the Pops (b008njrq) of his life to the NHS, from an ambitious 18-year-old seeking a Classic edition of Top of the Pops from 1968, presented by SAT 19:00 The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby place at St Mary's Medical School, through 100 hour weeks as a Jimmy Savile and Dave Cash. Artists featured include The (b008njlp) junior doctor and 14 years of exams to become a consultant. Foundations, The Alan Price Set, Brenton Wood, Hermans Episode 8 Now an established consultant radiologist, Nick faces a Hermits, Status Quo, The Move and Amen Corner. worrying future. With long waiting lists for scans, the Adaptation of the RSC's acclaimed 1980s stage production of Department of Health is making tough decisions in the name of the epic Dickens tale. Sir Mulberry Hawk returns to society. efficiency. MON 21:30 Juke Box Jury (b008njrr) Madeline is promised to Arthur Gride. Smike is taken ill and Classic 1950s and 60s pop music show in which a panel votes Nicholas and Kate take him to their home in Devon. hit or miss on the new releases they are played. David Jacobs SUN 19:30 BBC Proms (b007xljj) presents, with Nina and Frederick, Jill Ireland and David 2007 McCallum on the panel. SAT 20:00 The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby (b008njlq) Simon Bolivar National Youth Orchestra of Venezuela Episode 9 MON 22:00 Story of Light Entertainment (b0074tnd) Katie Derham introduces another extraordinary Prom from the Pop and Easy Listening Adaptation of the RSC's acclaimed 1980s stage production of BBC archive. -

Nicholas Nickleby

LEVEL 4 Teacher’s notes Teacher Support Programme Nicholas Nickleby Charles Dickens Chapters 3–4: Nicholas finds life at Dotheboys hard and is appalled by the cruel treatment given the to boys and to Smike, who runs away. Nicholas has a fistfight with Squeers and leaves the school. On his way back to London, Nicholas finds Smike and agrees to take him with him. Nicholas finds cheap lodgings in London and a job as a private French teacher. When Nicholas visits his mother and sister, he overhears his uncle telling them that he is a thief who has stolen a ring from Squeers and has run away with one of the children. Nicholas argues with Ralph and tries to defend himself from all the accusations but finally decides to leave London once again so as to protect his mother and sister. Summary Chapters 5–6: In London, Kate finds a job as Mrs Wititterly’s companion. Unfortunately, one of Ralph’s best The Nicklebys (Nicholas, his mother, sister Kate) are customers, Sir Mulberry Hawk, likes Kate and insists on penniless after the death of Mr Nickleby. In their poverty spending time with her despite her turning him down. and desperation they seek help from Nicholas’s Uncle Kate asks Ralph for help but he refuses to lose his best Ralph, a mean-spirited, cruel moneylender. Nicholas’s client. Newman Noggs overhears the conversation and independent attitude angers Ralph and Nicholas is sent writes to Nicholas, who decides to come back to London. away to Dotheboys Hall to teach. He is upset by the Nicholas fights Sir Mulberry and orders him to stay away mistreatment of the children there by Headmaster from his sister. -

The Personal History and Experience of David Copperfield the Younger Charles Dickens

The Personal History and Experience of David Copperfield the Younger Charles Dickens The Harvard Classics Shelf of Fiction, Vols. VII & VIII. Selected by Charles William Eliot Copyright © 2001 Bartleby.com, Inc. Bibliographic Record Contents Biographical Note Criticisms and Interpretations I. By Andrew Lang II. By John Forster III. By Adolphus William Ward IV. By Gilbert K. Chesterton V. By W. Teignmouth Shore VI. By George Gissing List of Characters Preface to the First Edition Preface to the “Charles Dickens” Edition I. I Am Born II. I Observe III. I Have a Change IV. I Fall Into Disgrace V. I Am Sent Away from Home VI. Enlarge My Circle of Acquaintance VII. My “First Half” at Salem House VIII. My Holidays. Especially One Happy Afternoon IX. I Have a Memorable Birthday X. I Become Neglected, and Am Provided For XI. I Begin Life on My Own Account, and Don’t Like It XII. Liking Life on My Own Account No Better, I Form a Great Resolution XIII. The Sequel of My Resolution XIV. My Aunt Makes up Her Mind about Me XV. I Make Another Beginning XVI. I Am a New Boy in More Senses Than One XVII. Somebody Turns Up XVIII. A Retrospect XIX. I Look about Me, and Make a Discovery XX. Steerforth’s Home XXI. Little Em’ly XXII. Some Old Scenes, and Some New People XXIII. I Corroborate Mr. Dick and Choose a Profession XXIV. My First Dissipation XXV. Good and Bad Angels XXVI. I Fall into Captivity XXVII. Tommy Traddles XXVIII. Mr. Micawber’s Gauntlet XXIX. -

DICKENS FINAL with ILLUS.Ppp

The Dickens Calendar 2012 The Dickens Calendar 2012 Celebrating the bicentenary of Dickens’s birth. £6.00 each or £10.00 for 2 (plus postage) Contact Jarndyce to order your copy: Email: [email protected] Phone: 020 7631 4220 35 _____________________________________________________________ Jarndyce Antiquarian Booksellers 46, Great Russell Street Telephone: 020 - 7631 4220 (opp. British Museum) Fax: 020 - 7631 1882 Bloomsbury, Email: [email protected] London WC1B 3PA V.A.T. No. GB 524 0890 57 _____________________________________________________________ CATALOGUE CXCV WINTER 2011-12 THE DICKENS CATALOGUE Catalogue: Joshua Clayton Production: Carol Murphy All items are London-published and in at least good condition, unless otherwise stated. Prices are nett. Items on this catalogue marked with a dagger (†) incur VAT (current rate 20%) A charge for postage and insurance will be added to the invoice total. We accept payment by VISA or MASTERCARD. If payment is made by US cheque, please add $25.00 towards the costs of conversion. Email address for this catalogue is [email protected]. JARNDYCE CATALOGUES CURRENTLY AVAILABLE, price £5.00 each include: Social Science Parts I & II: Politics & Philosophy and Economics & Social History. Women III: Women Writers J-Q; The Museum: Books for Presents; Books & Pamphlets of the 17th & 18th Centuries; 'Mischievous Literature': Bloods & Penny Dreadfuls; The Social History of London: including Poverty & Public Health; The Jarndyce Gazette: Newspapers, 1660 - 1954; Street Literature: I Broadsides, Slipsongs & Ballads; II Chapbooks & Tracts; George MacDonald. JARNDYCE CATALOGUES IN PREPARATION include: The Museum: Jarndyce Miscellany; The Library of a Dickensian; Women Writers R-Z; Street Literature: III Songsters, Lottery Puffs, Street Literature Works of Reference. -

King Lear a Sourcebook

William Shakespeare's King Lear A Sourcebook Edited by Grace loppolo Routledge R Taylor & Francis Group LONDON AND NEW YORK Contents List of Illustrations xi Annotation and Footnotes xii Acknowledgements xiii Introduction I I: Contexts Contextual Overview 9 General Note 14 Chronology IS Sources of King Lear 19 Primary Sources 19 From Geoffrey of Monmouth, Historia Regum Britanniae (c.1135) 19 From Raphael Holinshed, The Historie of England (1587) 23 From Anonymous, The True Chronicle Historie of King Leir and his three daughters (1605) 25 Secondary Sources 32 From John Higgins, The First Parte of the Mirour for Magistrates (1574) 32 From Edmund Spenser, The Faerie Queene (1596) 36 From Sir Philip Sidney, The Countesse of Pembroke's Arcadia (1590) 38 From Samuel Harsnett, A Declaration of Egregious Popish Impostures (1603) 40 From James I, The True Law of Free Monarchies (1598) 40 From James I, Basilikon Doron (1603) 41 viii CONTENTS 2: Interpretations Critical History 45 Early Critical Reception 48 From Charles Gildon, 'Remarks on the Plays of Shakespear' (1710) 48 From Lewis Theobald, Notes on King Lear (173 3) 48 From Samuel Johnson, Notes on King Lear (1765) 49 From Charles Lamb, 'On the Tragedies of Shakespeare' (1810) 50 From William Hazlitt, 'Characters of Shakespear's Plays: King Lear' (1817) 51 From Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Records of his Lecture on King Lear (1819) 53 John Keats, 'On Sitting Down to Read King Lear Once Again' (1818) 53 Modern Criticism 55 From A. C. Bradley, Shakespearean Tragedy: Hamlet, Othello, King Lear and Macbeth (1904) 55 From Jan Kott, Shakespeare Our Contemporary (1967) 56 From Peter Brook, The Empty Space (1968) 58 From R.