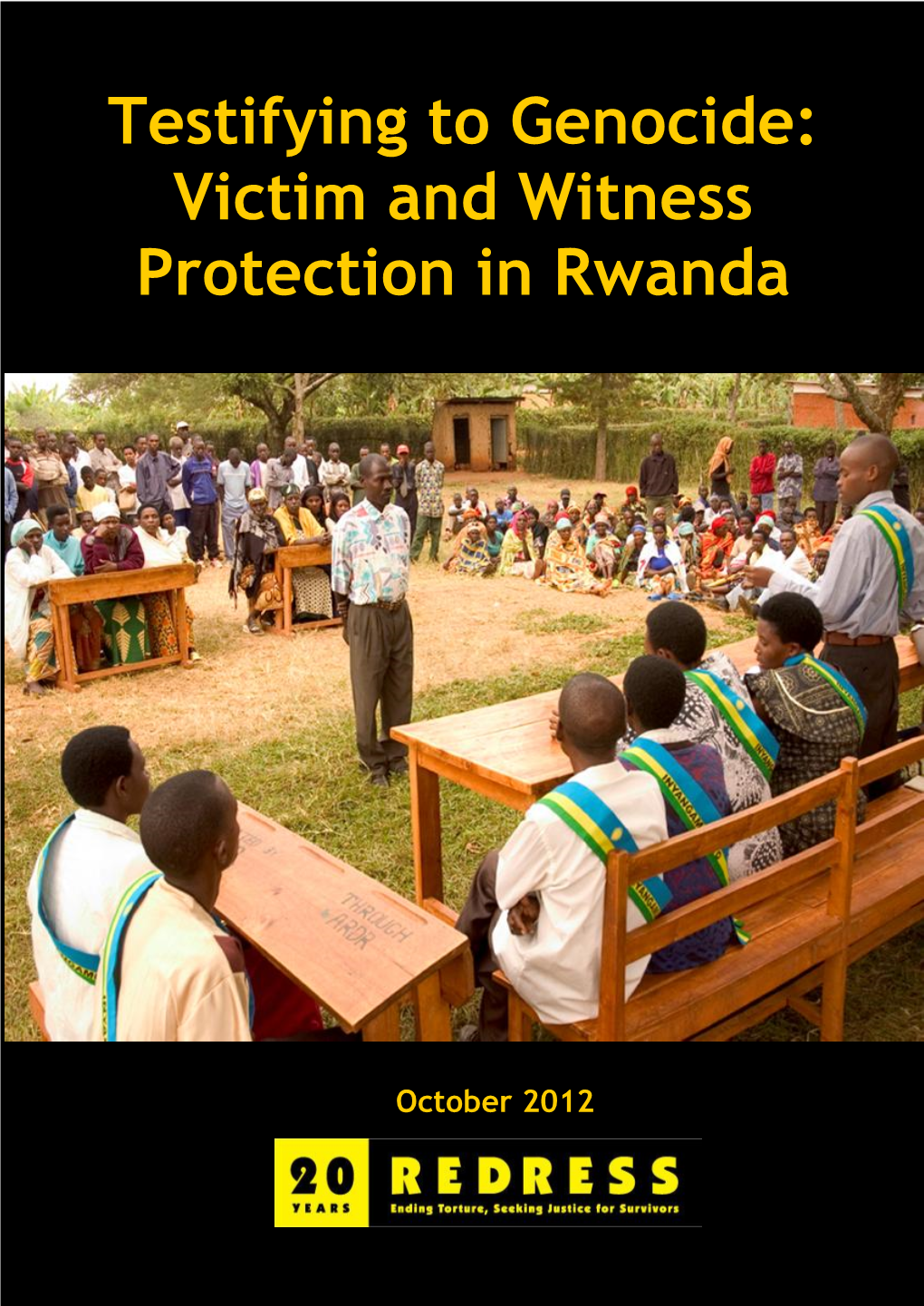

Testifying to Genocide: Victim and Witness Protection in Rwanda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rwanda Urban Development Project Phase Ii for Six Secondary Cities

Public Disclosure Authorized RWANDA URBAN DEVELOPMENT PROJECT PHASE II FOR SIX SECONDARY CITIES Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized ABBREVIATED RESETTLEMENT ACTION PLAN HUYE SECONDARY CITY Public Disclosure Authorized NOVEMBER 2019 Huye City ARAP Report Final i November 2019 ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT (ESIA) AND ABBREVIATED RESETTLEMENT ACTION PLANS (RAP) FOR RWANDA URBAN DEVELOPMENT PROJECT (RUDP) – PHASE 2. FINAL ARAP REPORT CONTENTS Chapter Description Page LIST OF APPENDICES vi LIST OF OTHER VOLUMES vii LIST OF FIGURES viii LIST OF TABLES ix DEFINITIONS x ABBREVIATIONS xiv EXECUTIVE SUMMARY xvi 1 INTRODUCTION 1-1 1.1 Background and Objectives 1-1 1.1.1 Project Background 1-1 1.1.2 Project Objectives 1-1 1.2 Authority of the Report 1-1 1.3 Project Location 1-2 1.4 Objectives of the Resettlement Action Plan study 1-3 1.5 Methodology 1-4 1.5.1 Desktop Studies 1-4 1.5.2 Site Verification and Assessment 1-4 1.5.3 Sensitization of Project Affected Persons 1-4 (a) Public Meetings 1-4 (b) Official letters 1-5 (c) Utility companies 1-5 1.5.4 Determination of the Socio-economic Profile of PAPs 1-5 1.5.5 Preparation of the Land Acquisition Plan 1-6 1.5.6 Land and Asset Valuation 1-6 (a) Land Valuation 1-7 (b) Buildings/structures 1-8 (c) Crops, plants and trees 1-8 1.6 Cut-Off Dates for Compensation 1-9 1.7 Challenges Encountered During the Assignment. 1-9 2 PROJECT DESCRIPTION 2-1 Huye City ARAP Report Final ii November 2019 2.1 RUDP Phase 2 Project 2-1 2.1.1 Selected Roads that would be upgraded in RUDP phase 2 including link-up footpaths 2-1 2.1.2 Stand-alone Drains and Outfall Drains 2-1 2.2 RUDP Phase 2 Sub-Project Components 2-2 2.2.1 Proposed Project Roads 2-2 (a) Selection of Road Corridors to be implemented 2-6 (b) Selected Road Designs 2-7 2.2.2 Stand-alone Drains and Outfall Drains Designs. -

Report 1 Preliminary Analysis and Diagnosis

Developing Rwandan Secondary Cities as Model Green Cities with Green Economic Opportunities Report 1 Preliminary Analysis and Diagnosis Musanze Secondary City, Rwanda Rwanda Country Program March 2015 Developing Rwandan Secondary Cities as Model Green Cities with Green Economic Opportunities Report 1: Preliminary Analysis and Diagnosis This document is paginated for a two-sided printing. © Republic of Rwanda Ministry of Infrastructure © Global Green Growth Institute - Rwanda Country Program 19F Jeongdong Bldg. 21-15 Jeongdong-gil Jung-gu Seoul 100-784 Republic of Korea Table of Contents Table of Figures 5 List of Tables 5 Acronyms 7 Glossary 9 Executive Summary 13 Introduction 17 1.1 Project Background and Objectives 17 1.2 Overall Activities 18 1.2.1 Urbanization and Rural Settwlement Sector Strategic Plan 2012/13-17/18 18 1.2.2 National Strategy for Climate Change and Low-Carbon Development 19 1.3 The Secondary Cities 20 1.4 Scope of the Project 20 1.4.1 Component 1 21 1.4.2 Component 2 21 1.4.3 Component 3 21 1.5 Introduction to this report 22 Quantitative and Qualitative Analysis of the District Development Level . 25 2.1 Introduction 25 2.2 National Economic Profile 25 2.2.1 Services and Infrastructure 25 2.2.2 Agriculture 26 2.2.3 Industry 27 2.2.4 Trade performance 27 2.2.5 Sustainable Tourism 27 2.3 General District Profiles 27 2.3.1 City of Kigal 30 2.3.2 Huye 30 2.3.3 Muhanga 31 2.3.4 Nyagatare 32 2.3.6 Musanze 32 2.3.7 Risizi 33 2.4 District Development Index (DDI) 33 2.4.1 Specific Methodology 33 2.4.2 Key Findings 36 2.4.3 -

Final Draft Report

ITAU AUDITORS LTD RWANDA ENVIRONMENT MANAGEMENT AUTHORITY Evaluation of National Environment Youth Project(NEYP) Final Draft Report ITAU AUDITORS LTD Kigali, January 2013 1 CONTENTS CONTENTS................................................................................................................................... 2 LIST OF TABLES ........................................................................................................................ 5 LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................................................... 6 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................................... 7 CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................... 9 1.1 PURPOSE OF THE EVALUATION .............................................................................................................. 9 1.2. KEY ISSUES ADDRESSED ......................................................................................................................... 9 1.3. METHODOLOGY ................................................................................................................................... 10 1.3.1. Secondary Data collection ................................................................................................................ 10 1.3.2. Primary Data collection .................................................................................................................... -

Analysis of the Causes of Financial And

ANALYSIS OF THE CAUSES OF FINANCIAL AND NON- FINANCIAL WEAKNESSES IDENTIFIED IN THE AUDITOR GENERAL’S REPORTS OF DECENTRALIZED ENTITIES FOR THE FINANCIAL YEAR ENDING 30 JUNE 2014 www.tirwanda.orgwww.tirwanda.org Transparency International Rwanda is a local chapter of a global movement with one vision: a world in which government, business, civil society and the daily lives of people are free of corruption. Since 2004, we are contributing to the fight against corruption in Rwanda to turn this vision into reality. www.tirwanda.org 2 © 2015 Transparency International Rwanda. All rights reserved. Every effort has been made to verify the accuracy of the information contained in this report. All information was believed to be correct as of December 2015. Nevertheless, Transparency International Rwanda cannot accept responsibility for the consequences of its use for other purposes or in other contexts. www.tirwanda.orgwww.tirwanda.org EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Transparency International Rwanda (TI-Rw) analyses expenditure- and non-expenditure related weaknesses of decentralized entities as highlighted in the Auditor General’s Report since 2012. The present analysis, a third of its kind, has focused on the reports for the financial year ending June, 2014 for all districts and the City of Kigali. This report is intended to broad audience including both interested public and public finance and local government stakeholders. The total monetary value related to the identified weaknesses in districts reached 112,650,524,574 RWF in the financial year 2013/14. This is a slight improvement to the year 2012/13. Still, this decrease marks only a marginal improvement equivalent to 1% of all identified weaknesses. -

Assessment of Development Results: Rwanda

ASSESSMENT OF DEVELOPMENT RESULTS EVALUATION OF UNDP CONTRIBUTION RWANDA Evaluation Office, May 2008 United Nations Development Programme REPORTS PUBLISHED UNDER THE ADR SERIES Bangladesh Montenegro Bhutan Mozambique Bulgaria Nicaragua China Nigeria Colombia Rwanda Republic of the Congo Serbia Egypt Sudan Ethiopia Syrian Arab Republic Honduras Ukraine India Turkey Jamaica Viet Nam Jordan Yemen Lao PDR EVALUATION TEAM Team Leader Betty Bigombe Team Members Klaus Talvela Samuel Rugabirwa Research Assistant Elizabeth K. Lang ASSESSMENT OF DEVELOPMENT RESULTS: RWANDA Copyright © UNDP 2008, all rights reserved. Manufactured in the United States of America The analysis and recommendations of this report do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations Development Programme, its Executive Board or the United Nations Member States. This is an independent publication by UNDP and reflects the views of its authors. Design: Suazion Inc. (NY, suazion.com) Production: A.K. Office Supplies (NY) FOREWORD The Evaluation Office of UNDP conducts highly relevant. However, results have been independent country-level evaluations called diminished by the sometimes less-than-optimal Assessments of Development Results (ADRs). delivery of UNDP services. This is a problem These assess the relevance and strategic positioning with many UNDP country offices. While UNDP of UNDP support and its contributions to a has made considerable progress towards a more country’s development over a given period of sustainable long-term development approach, it time. The aim of the ADR is to generate lessons still suffers from being dispersed across too many that can strengthen programming at the country thematic areas. This impedes UNDP efforts to level and contribute to the organization’s improve programme administration and technical effectiveness and accountability. -

Organic Law No 29/2005 of 31/12/2005 Determining The

Year 44 Special Issue of 31st December 2005 OFFICIAL GAZETTE OF THE REPUBLIC OF RWANDA Nº 29/2005 of 31/12/2005 Organic Law determining the administrative entities of the Republic of Rwanda. Annex I of Organic Law n° 29/2005 of 31/12/2005 determining the administrative entities of the Republic of Rwanda relating to boundaries of Provinces and the City of Kigali. Annex II of Organic Law n° 29/2005 of 31/12/2005 determining the administrative entities of the Republic of Rwanda relating to number and boundaries of Districts. Annex III of Organic Law n° 29/2005 of 31/12/2005 determining the administrative entities of the Republic of Rwanda relating to structure of Provinces/Kigali City and Districts. 1 ORGANIC LAW Nº 29/2005 OF 31/12/2005 DETERMINING THE ADMINISTRATIVE ENTITIES OF THE REPUBLIC OF RWANDA We, KAGAME Paul, President of the Republic; THE PARLIAMENT HAS ADOPTED AND WE SANCTION, PROMULGATE THE FOLLOWING ORGANIC LAW AND ORDER IT BE PUBLISHED IN THE OFFICIAL GAZETTE OF THE REPUBLIC OF RWANDA THE PARLIAMENT: The Chamber of Deputies, in its session of December 2, 2005; The Senate, in its session of December 20, 2005; Given the Constitution of the Republic of Rwanda of June 4, 2003, as amended to date, especially in its articles 3, 62, 88, 90, 92, 93, 95, 108, 118, 121, 167 and 201; Having reviewed law n° 47/2000 of December 19, 2000 amending law of April 15, 1963 concerning the administration of the Republic of Rwanda as amended and complemented to date; ADOPTS: CHAPTER ONE: GENERAL PROVISIONS Article one: This organic law determines the administrative entities of the Republic of Rwanda and establishes the number, boundaries and their structure. -

Rwanda: Livestock Disease Management and Food Safety Brief

Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Livestock Systems Rwanda: Livestock Disease Management and Food Safety Brief May 2016 The Management Entity at the University of Florida Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Livestock Systems Rwanda: Livestock Disease Management and Food Safety Brief 2 Acknowledgement The Livestock Disease Management and Food Safety Brief was prepared by Ashenafi Feyisa Beyi, graduate student, under the supervision of Dr. Arie Hendrik Havelaar, Department of Animal Science, and Dr. Jorge Hernandez, Department of Large Animal Clinical Sciences. This Brief is a work in progress. It will be updated with additional information collected in the future. This Brief is made possible with the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) under the Feed the Future Initiative. The contents in this brief are the responsibility of the University of Florida and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government, and its partners in Feed the Future countries. Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Livestock Systems Rwanda: Livestock Disease Management and Food Safety Brief 3 1. Introduction In Rwanda, livestock plays a crucial role in rural and national economies and contributes 8.8% to the national gross domestic product (Karenzi et al., 2013). During the war of 1994, Rwanda lost 90% of its national cattle herd (Bazarusanga, 2008). In subsequent years, however, the livestock population has gradually increased and the proportion of Rwandan households keeping cattle has risen (34.4% in 2005/2006, 47.3% in 2010/2011, and 50.4% in 2013/2014; SYB, 2015). -

Rwanda Agriculture Board East and Central Africa Agriculture Transformation Project(Ecaatp)

REPUBLIC OF RWANDA RWANDA AGRICULTURE BOARD EAST AND CENTRAL AFRICA AGRICULTURE TRANSFORMATION PROJECT(ECAATP) Public Disclosure Authorized FINAL REPORT Public Disclosure Authorized RESETTLEMENT POLICY FRAMEWORK Public Disclosure Authorized April 2018 Public Disclosure Authorized 1 | P a g e EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Agriculture is the backbone of Rwanda’s economy, accounting for about 33 percent of GDP, 72% employment, and 25% of all exports. The total arable land in Rwanda is slightly above 1.5 million ha, 90% of which is found on hillsides. The agriculture sector faces several challenges: (i) a binding land constraint that rules out intensification (bringing more and more land under cultivation); (ii) small average land holdings (more than 60% of household cultivate less than 0.6 ha and 15% of rural farms less than 0.1 ha); (iii) poor water management (uneven rainfall and ensuing variability in production); (iv) the need for greater (public and private) capacity from the district to the national levels and insufficient extension services for farmers; and (v) limited commercial orientation constrained by poor access to output and financial markets. Without the option of continuous intensification, agricultural intensification must take place in the context of a potentially fertile, but challenging physical environment. Steep terrains and the highest population density in sub-Saharan Africa (355 inhabitants per km²) make good land husbandry practices a strict necessity (to curtail erosion and otherwise maintain the quality of the soil), as well as an environmental prerogative. Arable land on hillsides constitutes the vast majority of the total agricultural land in the country, but erosion costs the country 421 tons /ha of fertile soils per year. -

Quarterly Report

INZIRA NZIZA ACTIVITY Award No.: AID-696-F-17-00001 Quarterly Report Quarter 1I: 1 January -31 March 2019 Submitted by Never Again Rwanda Contact Person:Page Dr. 1 ofJoseph 45 Nkurunziza Executive Director Email:[email protected] Page 2 of 45 Contents 1. Project Description/Introduction ........................................................................................................ 4 2. Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................ 6 3. Activity implementation progress/ Accomplishments ................................................................. 7 3.1. Meet your Member of Parliament (MYMP) in Nyabihu District .............................................. 7 3.1. Radio and TV programs on youth participation in decision making processes and development ................................................................................................................................................... 9 3.2. Roundtable discussion in Gisagara District ................................................................................ 13 3.3. District exchange meetings in Nyamagabe and Nyabihu Districts ................................... 16 3.4. Joint trainings for youth and local leaders in Nyabihu and Ngororero Districts .............. 19 3.5. Public Forum Debate Competitions in Nyabihu and Ngororero Districts ......................... 32 3.7. The Face to Face Portal ................................................................................................................. -

Persistency of Poverty Among Female Headed Households in Rwanda: Case of Huye District

Journal of Humanities and Social Policy Vol. 4 No. 1 2018 ISSN 2545 - 5729 www.iiardpub.org Persistency of Poverty among Female Headed Households in Rwanda: Case of Huye District Hakizimana Emmanuel (MSW) Department of Child and Family Studies Faculty of Social Work Catholic University of Rwanda P.O. Box 49 Butare/Huye - Rwanda [email protected] Abstract Background: Women in general have been persistently poor in relation to men and particularly female headed households (FHHs) whose number has suddenly increased in Rwanda in the aftermath of 1994 genocide against Tutsis. They took the responsibility to cater for the families irrespective of their lower level of competition and the history that considered them as weaker sex. Aim: The purpose of the study was to assess the factors leading to the persistency of poverty among FHHs. Methods: This descriptive study used both quantitative and qualitative approaches to collect and analyze relevant information from 87 individuals from Huye District composed by FHHs, sector, district and ministerial staffs who accepted to participate in the study. Results: Respondents revealed that lower level of education; lack of self-esteem; small land for agricultural activities are among the main factors of poverty. The government through the community development policy established various strategies for women empowerment but still the poverty is persistent in rural areas Conclusion: An emphasis should be put on increasing entrepreneurship and cooperative management skills; and the sensitization of both men and women about gender equality would be of paramount importance. Key words: Persistency; poverty; female headed households; women; empowerment Introduction The United Nations Development Programme and The World’s Women asserted that long ago, women were considered to be the weaker sex, and would depend on men in almost all socio-economic matter. -

Population Size, Structure and Distribution

THE REPUBLIC OF RWANDA Thematic Report Population size, structure and distribution i Fourth Population and Housing Census, Rwanda, 2012 Rwanda, Census, and Housing Fourth Population NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF STATISTICS OF RWANDA ii THE REPUBLIC OF RWANDA Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda Fourth Population and Housing Census, Rwanda, 2012 Thematic Report Population size, structure and distribution January 2014 iii The Fourth Rwanda Population and Housing Census (2012 RPHC) was implemented by the National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda (NISR). Field work was conducted from August 16th to 30th, 2012. The funding for the RPHC was provided by the Government of Rwanda, World Bank (WB), the UKAID (Former DFID), European Union (EU), One UN, United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) and UN Women. Additional information about the 2012 RPHC may be obtained from the NISR: P.O. Box 6139, Kigali, Rwanda; Telephone: (250) 252 571 035 E-mail: [email protected]; Website: http://www.statistics.gov.rw. Recommended citation: National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda (NISR), Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning (MINECOFIN) [Rwanda], 2012. Rwanda Fourth Population and Housing Census. Thematic Report: Population size, structure and distribution iv Table of contents Table of contents ..................................................................................................................... v List of tables ............................................................................................................................vii -

Diversity of Non-Native Tree Populations in the Different Districts of Rwanda

Diversity of non-native tree populations in the different Districts of Rwanda ByTelesphore Kabera Department Of Civil, Environmental And Geomatics (CEGE) 34th Southern Forest Tree Improvement Conference June 19-22, 2017 Melbourne, Florida, USA WHY THIS STUDY? An office in charge of forestry under MINERENA was contacted and it was found that there is no reliable and up-to-date information on forest and tree resources regarding their number, wood volumes and growth, etc…. The status of forest industries is not well documented in Rwanda AIM The present study has the main objective to describe, examine, and discuss the current distribution of non- indigenous or native-trees, particularly Eucalyptus spp. in Rwanda. Based on the findings, it also aims to provide recommendations to the Directorate in charge of forestry under the Ministry of Natural Resources for better management of forests in Rwanda. 1. BACKGROUND Fig 1. Different districts of Republic of Rwanda Rwanda is a landlocked country situated in central/Eastern Africa bordered to the north by Uganda, to the east by Tanzania, to the south by Burundi and to the west by the Democratic Republic of Congo. Rwanda has a total population of 11,780,000 (2013 2 estimates) occupying an area of 26,338 km . (with a density among the highest more than 400 persons per Km2) Rwanda is composed of four provinces and Kigali-City. The Eastern Province is composed of seven Districts Kigali-City is composed of three Districts • The Southern Province is composed of eight Districts • The Norhern Province is composed of five Districts, which are • Finally, there is the Western province composed of seven Districts Rwanda faces a major problem in environmental protection due to: 1.