Bangladesh: Chittagong Hill Tracts Rural Development Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IPP: Bangladesh: Second Chittagong Hill Tracts Rural Development Project

Second Chittagong Hill Tracts Rural Development Project (RRP BAN 42248) Indigenous Peoples Plan March 2011 BAN: Second Chittagong Hill Tracts Rural Development Project Prepared by ANZDEC Ltd for the Ministry of Chittagong Hill Tracts Affairs and Asian Development Bank. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 16 March 2011) Currency unit – taka (Tk) Tk1.00 = $0.0140 $1.00 = Tk71.56 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank ADR – alternative dispute resolution AP – affected person CHT – Chittagong Hill Tracts CHTDF – Chittagong Hill Tracts Development Facility CHTRC – Chittagong Hill Tracts Regional Council CHTRDP – Chittagong Hill Tracts Rural Development Project CI – community infrastructure DC – deputy commissioner DPMO – district project management office GOB – Government of Bangladesh GPS – global positioning system GRC – grievance redress committee HDC – hill district council INGO – implementing NGO IP – indigenous people IPP – indigenous peoples plan LARF – land acquisition and resettlement framework LCS – labor contracting society LGED – Local Government Engineering Department MAD – micro agribusiness development MIS – management information system MOCHTA – Ministry of Chittagong Hill Tracts Affairs NOTE (i) In this report, "$" refers to US dollars. This indigenous peoples plan is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. 1 CONTENTS Page A. Executive Summary 3 B. -

Further Notable Bird Records from Bangladesh

FORKTAIL 19 (2003): 85-102 Further notable bird records from Bangladesh PAUL M. THOMPSON AND DAVID L. JOHNSON Details are given of 23 species new for Bangladesh that were recorded between June 1993 and June 2002, or that were inadvertently omitted from the most recent national checklist (Harvey 1990), or Thompson et al. (1993). New sightings and information are given for a further 101 species that either have few records since 1978, or for which there have been major changes in known status, or for which there is uncertainty over status. In addition, nine species of doubtful occurrence are discussed, and the status of threatened and Near Threatened species is updated where appropriate. Following a peace agreement, it has been possible to travel in many areas of the Chittagong Hill Tracts since late 1998; this area had been closed to outsiders since the 1960s. This has opened the possibility of rediscovering many species known in Bangladesh only from older or uncertain records, but unfortunately most of the original forest cover of this area has now been lost. INTRODUCTION season), are flooded and merge to form a vast inland sea. In the dry season, the water area is reduced to a Harvey (1990) summarised the current status of birds number of lakes, termed beels, within each haor. The in Bangladesh and included in his list a number of term char refers to recently accreted sandy-silt islands species new for Bangladesh. This was updated and located in the main rivers and coastal areas. expanded by Thompson et al. (1993). The purpose of An important change that has taken place within the this paper is to further update status information on period covered by this paper is that a peace agreement birds in Bangladesh. -

Bangladesh Needs Assessment Working Group (NAWG) Report on Landslides

Bangladesh Needs Assessment Working Group (NAWG) Report on Landslides Landslides, Bangladesh, June 2017 Report date: 19 June 2017 (Source: UNICEF) Md. Yousuf Ali, Director-MIM, DDM, Email: [email protected] Contact for Inquiries: Arshad Muhammad, Assistant Country Director – Programs , CARE, Email: [email protected] Landslides, Bangladesh June 2017 Contents Contents 2 Background 3 Key Findings 4 Context of the Affected Area 6 Key characteristics of the affected districts by the landslides 8 Situation Overview 10 Detailed Findings 15 Access and Infrastructure 15 Communication 16 Child Protection 18 Education 19 Food Security 20 Livelihoods and Income 20 Gender Based Violence 21 Gender 23 Health 23 Market 25 Nutrition 26 Shelter 27 Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) 28 Annex A: Affected people per Upazila 30 2 Landslides, Bangladesh June 2017 Background On June 13th the districts of Bandarban, Chittagong, Rangamati, Khagrachari and Cox’s Bazaar suffered from possibly the deadliest landslides in their history. The disaster killed an estimated 160 persons, including 115 persons in Rangamati alone. According to the Chittagong Divisional Health Office Control Room Report, a total of 187 injured persons were admitted in local level hospitals. Approximately 85% of patients were admitted in Rangamati. While landslide related disaster occurs nearly every year, the second highest death toll of 127 deceased persons was recorded in 2007 [Disaster Forum, June 2017]. Monsoon rains caused severe flooding in low-lying areas to significantly damage road and communication infrastructure. Flood water rendered remote communities in Bandarban, Chittagong, and Rangamati districts were inaccessible by road. On June 14th, mudslides in southeast Bangladesh claimed additional lives in Cox's Bazaar and Khagrachari districts to further damage homes and infrastructure. -

Bangladesh: Second Chittagong Hill Tracts

Initial Environmental Examination for the Kafru Para, Sorio Union Subproject February 2011 BAN: Second Chittagong Hill Tracts Rural Development Project Prepared by ANZDEC Ltd for the Ministry of Chittagong Hill Tracts Affairs and the Asian Development Bank. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 16 March 2011) Currency unit – taka (Tk) Tk1.00 = $0.0140 $1.00 = Tk71.56 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank CHT – Chittagong Hill Tracts CHTRC – Chittagong Hill Tracts Regional Council CHTRDP-I – Chittagong Hill Tracts Rural Development Project DOE – Department of Environment EARF – Environmental Assessment Review Framework EMMP – Environmental Management and Monitoring Plan IEE – Initial Environmental Examination IP – indigenous people LGED – Local Government Engineering Department MOCHTA – Ministry of Chittagong Hill Tracts Affairs O&M – operation and maintenance PPTA – project preparatory technical assistance GLOSSARY jhum – swidden or shifting cultivation mouza – a small administrative area usually composed of a number of villages para – administrative division – subdivision of a Union Union – administrative division – subdivision of an upazila upazila – administrative division – subdivision of a district NOTE (i) In this report, "$" refers to US dollars. This initial environmental examination is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Initial Environmental Examination for the Kafru Para, Soroi Union Subproject (SSP4) Table of Contents A. -

Situation Report 16

Situation Report No. #16 15 June 2020 https://www.who.int/bangladesh/emergencies/coronavirus-disease-(covid-19)-update/coronavirus-disease-(covid-2019)-bangladesh-situation-reports Photo: Social Media Bangladesh Tested Confirmed Recovered Dead Hotline 519,503 90,619 14,560 1,209 11,310,820 Test/1 million New Cases Recovery Rate CFR% AR/1 million 3,050 3,099 20.6% 1.33% 532.1 Laboratories Gender PPE Stock PoE Screening 60 COVID-19 Labs 70% 30% 1,392,601 344,067 Last Days 106,478 Samples 3,135,420 22,607 63.7% Inside Dhaka Tests 562,439 7,029 17.4% Share of Positive Tests 179,759 345,218 WHO Bangladesh COVID-19 Situation Report #16 15 June 2020 1. Highlights As of 15 June 2020, according to the Institute of Epidemiology, Disease Control and Research (IEDCR), there are 90,619 confirmed COVID-19 cases in Bangladesh, including1,209 related deaths; Case Fatality Rate (CFR) is 1.33%. On 12 June 2020, the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare/DGHS introduced “Bangladesh Risk Zone-Based COVID- 19 Containment Implementation Strategy/Guide,” dividing areas in Red, Yellow and Green Zone based on the prevailing risk of the COVID-19 spread. On 13 June 2020, the Ministry of Religious Affairs, Coordination Branch issued an Emergency Notification circular with the instructions for the worshipers in the Red Zone areas to offer prayers at their respective homes instead of public place of worship. On 14 June 2020, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MoFA) circulated a Note Verbale, which stated that foreign investors and businessmen will be granted on-arrival visas at the port of entry in Bangladesh if he/she has a PCR-based COVID- 19 negative medical certificate (with English translation) and relevant supporting documents for obtaining investment/business visa. -

Farmers' Organizations in Bangladesh: a Mapping and Capacity

Farmers’ Organizations in Bangladesh: Investment Centre Division A Mapping and Capacity Assessment Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) Viale delle Terme di Caracalla – 00153 Rome, Italy. Bangladesh Integrated Agricultural Productivity Project Technical Assistance Component FAO Representation in Bangladesh House # 37, Road # 8, Dhanmondi Residential Area Dhaka- 1205. iappta.fao.org I3593E/1/01.14 Farmers’ Organizations in Bangladesh: A Mapping and Capacity Assessment Bangladesh Integrated Agricultural Productivity Project Technical Assistance Component Food and agriculture organization oF the united nations rome 2014 Photo credits: cover: © CIMMYt / s. Mojumder. inside: pg. 1: © FAO/Munir uz zaman; pg. 4: © FAO / i. nabi Khan; pg. 6: © FAO / F. Williamson-noble; pg. 8: © FAO / i. nabi Khan; pg. 18: © FAO / i. alam; pg. 38: © FAO / g. napolitano; pg. 41: © FAO / i. nabi Khan; pg. 44: © FAO / g. napolitano; pg. 47: © J.F. lagman; pg. 50: © WorldFish; pg. 52: © FAO / i. nabi Khan. Map credit: the map on pg. xiii has been reproduced with courtesy of the university of texas libraries, the university of texas at austin. the designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and agriculture organization of the united nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. the mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. -

FILLING STATION) Page # 1 A/C No A/C NAME Address DHAKA 3020047 AMIN PETROL PUMP SECRETARIAT ROAD DHAKA 3020062 A

PADMA OIL COMPANY LIMITED AGENT/CUSTOMER LIST DEALER (FILLING STATION) Page # 1 A/C No A/C NAME Address DHAKA 3020047 AMIN PETROL PUMP SECRETARIAT ROAD DHAKA 3020062 A. HYE & CO. HATKHOLA ROAD, DHAKA 3020096 GREEN VIEW PETROL PUMP GREEN ROAD, DHAKA 3020112 L. RAHMAN & OSMAN GHANI & SONS MYMENSINGH ROAD DHAKA 3020138 M. AZIM ZULFIQUAR & SONS KARWAN BAZAR,TEJGAON DHAKA 3020146 MAINUDDIN AKHTARUDDIN CHOWDHURY 159,BAJEKAKRAIL DHAKA - 2 3020153 MARGARETT & SONS 17, AIRPORT ROAD TEJGAON, DHAKA 3020161 DHAKA DIST.POLICE WELFARETRUST POLWEL FILLING STAT. MILL BARRACK 3020179 AZIZ CORPORATION 36, DILKUSHA C/A DHAKA 3020187 BANGLADESH PWD SPORTS CLUB ASAD GATE, DHAKA 3020195 MIRPUR PETROL PUMP 3, JIKATULI, MIRPUR DHAKA 3020203 KURMITOLA PETROL PUMP DHAKA CANTONMENT DHAKA 3020211 GULASHAN AUTOS GULSHAN AREA, DHAKA 3020229 JOYDEBPUR FILLING STATION P.O.JOYDEBPUR, DHAKA 3020237 MALIBAGH AUTO SERVICE MALIBAGH,WARI ROAD DHAKA 3020245 MOUCHAK BOYSCOUT FILLING STATION MAUCHAK, DHAKA 3020252 PUBALI TRADERS ROAD NO.30,HOUSE NO. 708,DHANMONDI R/A 3020278 PATHER BANDHU NEW MARKET, DHAKA 3020286 PURBACHAL TRADERS MYMENSINGH ROAD PARIBAGH, DHAKA 3020302 RUPALI FILLING STATION 29, KALICHARAN SAHA ROAD, DHAKA 3020310 ABDUR RAHMAN 'PATHIK' 166, NAWABPUR ROAD DHAKA 3020328 MESSRES SHARATHI 13,SYED GOLAM MOSTAFA LANE, DHAKA 3020336 RAMNA FILLING STATION 21,DHANMONDI R/A DHAKA - 5 3020344 MESSRES SHOHAG PROP. HASHMAT ALI DHAKA 3020369 M. AKHTAR HOSSAIN JATRABARI, DHAKA 3020377 BENGAL INTERNATIONAL AGENCY DHANMONDI, DHAKA 3020385 SATATA & CO. MOHAMMADPUR, DHAKA 3020401 NESSA & SONS MIRPUR, DHAKA 3020427 EASTERN FILLING STATION TEMINATED-APS: 3/71, 15/10/2001 ALLENBARI,TEJGAON, 3020435 SARWAR FILLING STATION AMIN BAZAR, MIRPUR DHAKA 3020443 PALTAN SERVICE STATION 61, PURANA PALTAN DHAKA 3020450 B.D POLICE CO-OPERATIVE SOCIETY LTD. -

Division Zila Upazila Name of Upazila/Thana 10 10 04 10 04

Geo Code list (upto upazila) of Bangladesh As On March, 2013 Division Zila Upazila Name of Upazila/Thana 10 BARISAL DIVISION 10 04 BARGUNA 10 04 09 AMTALI 10 04 19 BAMNA 10 04 28 BARGUNA SADAR 10 04 47 BETAGI 10 04 85 PATHARGHATA 10 04 92 TALTALI 10 06 BARISAL 10 06 02 AGAILJHARA 10 06 03 BABUGANJ 10 06 07 BAKERGANJ 10 06 10 BANARI PARA 10 06 32 GAURNADI 10 06 36 HIZLA 10 06 51 BARISAL SADAR (KOTWALI) 10 06 62 MHENDIGANJ 10 06 69 MULADI 10 06 94 WAZIRPUR 10 09 BHOLA 10 09 18 BHOLA SADAR 10 09 21 BURHANUDDIN 10 09 25 CHAR FASSON 10 09 29 DAULAT KHAN 10 09 54 LALMOHAN 10 09 65 MANPURA 10 09 91 TAZUMUDDIN 10 42 JHALOKATI 10 42 40 JHALOKATI SADAR 10 42 43 KANTHALIA 10 42 73 NALCHITY 10 42 84 RAJAPUR 10 78 PATUAKHALI 10 78 38 BAUPHAL 10 78 52 DASHMINA 10 78 55 DUMKI 10 78 57 GALACHIPA 10 78 66 KALAPARA 10 78 76 MIRZAGANJ 10 78 95 PATUAKHALI SADAR 10 78 97 RANGABALI Geo Code list (upto upazila) of Bangladesh As On March, 2013 Division Zila Upazila Name of Upazila/Thana 10 79 PIROJPUR 10 79 14 BHANDARIA 10 79 47 KAWKHALI 10 79 58 MATHBARIA 10 79 76 NAZIRPUR 10 79 80 PIROJPUR SADAR 10 79 87 NESARABAD (SWARUPKATI) 10 79 90 ZIANAGAR 20 CHITTAGONG DIVISION 20 03 BANDARBAN 20 03 04 ALIKADAM 20 03 14 BANDARBAN SADAR 20 03 51 LAMA 20 03 73 NAIKHONGCHHARI 20 03 89 ROWANGCHHARI 20 03 91 RUMA 20 03 95 THANCHI 20 12 BRAHMANBARIA 20 12 02 AKHAURA 20 12 04 BANCHHARAMPUR 20 12 07 BIJOYNAGAR 20 12 13 BRAHMANBARIA SADAR 20 12 33 ASHUGANJ 20 12 63 KASBA 20 12 85 NABINAGAR 20 12 90 NASIRNAGAR 20 12 94 SARAIL 20 13 CHANDPUR 20 13 22 CHANDPUR SADAR 20 13 45 FARIDGANJ -

Tree Species Diversity of the Kaptai National Park in Rangamati District, Bangladesh

Jahangirnagar University J. Biol. Sci. 8(2): 71-79, 2019 (December) Tree species diversity of the Kaptai National Park in Rangamati district, Bangladesh Md. Mukhlesur Rahman*, M. Mahfuzur Rahman1 and Md. Kamrul Huda2 Bangladesh Forest Research Institute, Shulashahar, Chittagong, Bangladesh Abstract The purpose of this study was to estimate the tree biodiversity in the Kaptai National Park. The total area of the Kaptai National Park is about 4,564 ha (11,273.08 acres) under the jurisdiction of Rangamati South Forest Division, Rangamati Hill Tracts district. The study was conducted through extensive survey only on the tree species composition in the Kaptai National Park. During the investigation, a total of 65 tree species belonging to 29 families were recorded from the park. Among the plant families, Mimosaceae possessed the highest number of species (7) followed by Meliaceae (6), Ancardiaceae (5), Moraceae (4), Verbenaceae (4), Combretaceae (4), Myrtaceae (4), Dipterocarpaceae (3), Fabaceae (3), Rubiaceae (2), Bombacaceae (2), Caesalpiniaceae (2), Dilleniaceae (2) and Bignoniaceae (2) respectively. There were 15 families which contained single species. Tree species belonging to the family Mimosaceae was dominated in respect to number of species and their population as well. The findings of the present investigation will contribute in the regeneration of tree species in this degraded forest ecosystem and in the protection, conservation and sustainable management of the Kaptai National Park. Key words: Kaptai National park, native tree species, biodiversity. INTRODUCTION Bangladesh vegetation is a part of the Indo-Myanmar region, which is one of the most important hot spot areas for biodiversity (Mittermeir et al., 1980) and rich biological diversity due to its unique geophysical location (Hossain, 2001; Barua et al., 2001; Chowdhury 2001; Nishat et al., 2002). -

Second Chittagong Hill Tracts Rural Development Project

Environmental Monitoring Report Project No. 42248-013 Semestral Report July 2016 2763-BAN (SF): Second Chittagong Hill Tracts Rural Development Project Prepared by Mohammad Nurul Islam, Environmental Engineer, Independent Consultants, Safeguard and Quality Monitoring Cell Second Chittagong Hill Tracts Rural Development Project, for the Peoples Republic of Bangladesh and the Asian Development Bank. This environmental monitoring report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Environmental Monitoring Report January - July 2016 The People’s Republic of Bangladesh & Asian Development Bank Second Chittagong Hill Tracts Rural Development Project Loan № 2763-BAN, Project № 42248-013 Environmental Monitoring Report January - July 2016 Prepared by Mohammad Nurul Islam, Environmental Engineer (Independent Consultant) Safeguard and Quality Monitoring Cell Ministry of Chittagong Hill Tracts Affairs ii Chittagong Hill Tracts Rural Development Project-II Environmental Monitoring Report January - July 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS ............................................................................................ -

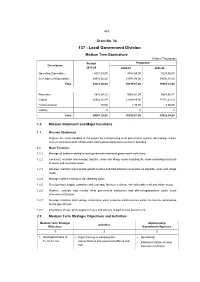

137 - Local Government Division

453 Grant No. 34 137 - Local Government Division Medium Term Expenditure (Taka in Thousands) Budget Projection Description 2019-20 2020-21 2021-22 Operating Expenditure 4321,54,00 4753,69,00 5229,06,00 Development Expenditure 29919,66,00 31541,98,00 34696,18,00 Total 34241,20,00 36295,67,00 39925,24,00 Recurrent 7815,04,16 9003,87,04 8807,80,41 Capital 26425,35,84 27289,84,96 31115,37,59 Financial Asset 80,00 1,95,00 2,06,00 Liability 0 0 0 Total 34241,20,00 36295,67,00 39925,24,00 1.0 Mission Statement and Major Functions 1.1 Mission Statement Improve the living standard of the people by strengthening local government system, developing climate resilient rural and urban infrastructure and implementing socio-economic activities. 1.2 Major Functions 1.2.1 Manage all matters relating to local government and local government institutions; 1.2.2 Construct, maintain and manage Upazilla, union and village roads including the roads and bridges/culverts of towns and municipal areas; 1.2.3 Develop, maintain and manage growth centres and hats-bazaars connected via Upazilla, union and village roads; 1.2.4 Manage matters relating to safe drinking water; 1.2.5 Develop water supply, sanitation and sewerage facilities in climate risk vulnerable rural and urban areas; 1.2.6 Finance, evaluate and monitor local government institutions and offices/organizations under Local Government Division; 1.2.7 Develop, maintain and manage small-scale water resource infrastructures within the timeline determined by the government. 1.2.8 Enactment of Law, promulgation of rules and policies related to local government. -

UNICEF's Work in the Chittagong Hill Tracts

For further information, please contact: AM Sakil Faizullah UNICEF Bangladesh [email protected] phone: +880 17 1304 9900 MANY TRACTS ONE COMMUNITY UNICEF’S Work in the Chittagong Hill Tracts Published by UNICEF Bangladesh BSL Offi ce Complex 1 Minto Road, Dhaka 1000, Bangladesh [email protected] www.unicef.org.bd © United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) August 2019 MANY TRACTS ONE COMMUNITY UNICEF’S Work in the Chittagong Hill Tracts Content Introduction p.5 Para Centres – the community hubs at the heart of UNICEF’s CHT programme p.8 Construction of new Para Centres p.9 Case Studies 1 Scarce water resources p.12 2 The child weaver p.13 3 The landslide victims p.14 42 The Para Centre Workers p.16 5 The Adolescents’ Group p.19 6 The Mothers’ Group p.20 7 Para Centre Management Committees p.21 8 Help For Mothers With Babies p.22 9 The Para Centre Teacher p.23 10 Para Centre Field Organiser p.24 11 Rangamati Government Hospital p.25 12 Government Health Assistant p.26 Conclusion p.28 Statistics sheets p.29 CHITTAGONG HILL TRACTS (CHT) INDIA BANGLADESH INDIA DHAKA INDIA KHAGRACHHARI RANGAMATI BANDARBAN Bay of Bengal MYANMAR DEMOGRAPHY Chittagong Khagrachhari Rangamati Bandarban Hill Tracts Total population 668,944 650,079 436,950 1,755,973 Share of population in the division (%) 2.16 2.10 1.41 6.67 Total under-eighteen population 265,391 257,907 173,351 696,649 Total under-five population 69,948 67,976 45,690 183,614 Population density per sq.