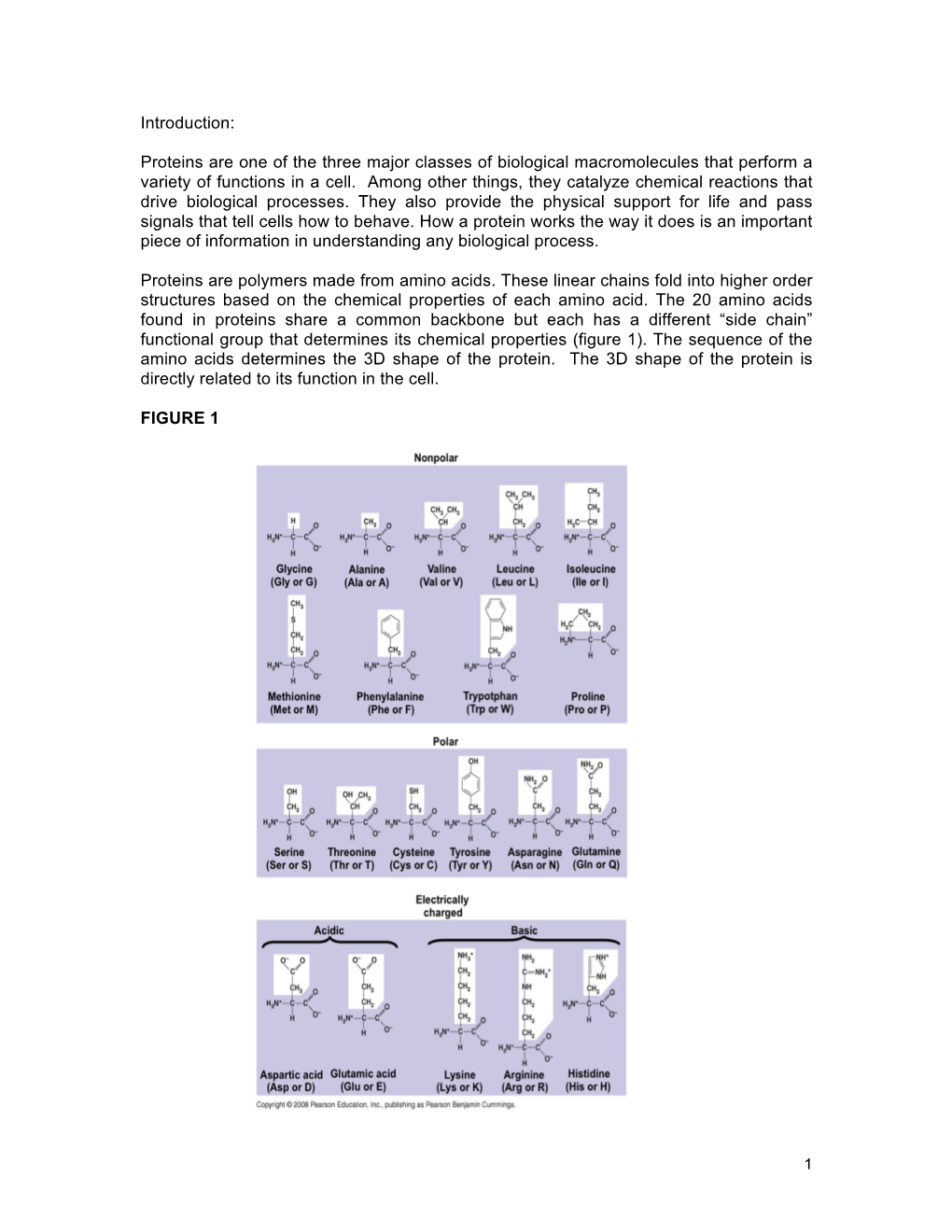

Introduction: Proteins Are One of the Three Major Classes of Biological

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Measurement and Interpretation of Diffuse Scattering in X-Ray Diffraction for Macromolecular Crystallography

Measurement and Interpretation of Diffuse Scattering in X-Ray Diffraction for Macromolecular Crystallography Workshop at the 2017 NSLS-II and CFN Users’ Meeting, Brookhaven National Laboratory, Upton, NY, May 15, 2017 Organizers: Michael Wall, [email protected] (LANL), Robert Sweet, [email protected] (NSLS-II, BNL), Nozomi Ando, [email protected] (Princeton University), James S. Fraser, [email protected] (University of California, San Francisco), George N. Phillips, Jr., [email protected] (Rice University) X-ray diffraction from macromolecular crystals includes both sharply peaked Bragg reflections and diffuse intensity between the peaks. The information in Bragg scattering reflects the mean electron density in the unit cells of the crystal. The diffuse scattering arises from correlations in the variations of electron density that may occur from one unit cell to another, and therefore contains information about collective motions in proteins. Leading researchers in diffuse scattering gathered May 15, 2017 for a one-day workshop at the NSLS-II Users’ Meeting. A major focus of the workshop was to provide a roadmap to the acquisition of reliable data by surveying measurement methods and discussing the increase in measurement accuracy enabled by improved detectors, experimental methods, and data integration. Another major focus was to survey examples of information that can be extracted about the behavior of biomolecules that would guide the thinking of biochemists and biologists. A number of talks addressed the measurement of diffuse-scattering data and advances in the modeling of the data in terms of conformational variation. Below we give a short synopsis of each talk, and at the end an analysis of the results of the workshop in total. -

Mathematical Virology Reidun Twarock

INFERENCE / Vol. 5, No. 3 Mathematical Virology Reidun Twarock ymmetry is ubiquitous in nature. It occurs in icosahedron from, 4, 8, and 20 equilateral triangles, respec- snowflakes, crystals, and molecules; and it is cen- tively. tral to our understanding of subatomic particles. Both the icosahedron and its dual, the dodecahedron, SAlthough the importance of symmetry in chemistry and possess icosahedral symmetry, and together they com- physics is widely appreciated, its significance in biology prise the largest rotational symmetry group in three is often underestimated. Viruses are notable examples of dimensions.3 Given a set of identical building blocks biological systems in which symmetry plays a pivotal role. under a repeating pattern of assembly, it is an icosahe- Mathematical techniques directed at understanding their drally symmetric shape that optimizes container volume. structure and symmetry have a transformative potential Since viruses are under selective pressure to package their both within virology and biology as a whole. genetic material efficiently, it is no surprise that evolution has forced their convergence to icosahedrally symmetric iral genomes are packaged in protein containers shapes. known as viral capsids. These containers function like Trojan horses, facilitating the release of the nlike other types of rotational symmetries in viralV genome into host cells and providing protection from three dimensions, icosahedral symmetry is non- host defense mechanisms between rounds of infection. In crystallographic: it is not possible to tessellate a their simplest form, viral capsids are less than 20 nano- Uthree-dimensional physical space using a single icosahe- meters (nm) in diameter and encapsulate short genomic drally symmetric shape without creating gaps or overlaps. -

Physics of Viral Dynamics

REVIEWS Physics of viral dynamics Robijn F. Bruinsma1, Gijs J. L. Wuite2 and Wouter H. Roos 3 ✉ Abstract | Viral capsids are often regarded as inert structural units, but in actuality they display fascinating dynamics during different stages of their life cycle. With the advent of single-particle approaches and high-resolution techniques, it is now possible to scrutinize viral dynamics during and after their assembly and during the subsequent development pathway into infectious viruses. In this Review, the focus is on the dynamical properties of viruses, the different physical virology techniques that are being used to study them, and the physical concepts that have been developed to describe viral dynamics. Capsids Humans and other animals, as well as plants, are plagued and new methods of analysis and numerical modelling. Protein shells that surround the by infections caused by viruses. These are parasites that We first review some of the dynamic methods that viral genome. cannot reproduce by themselves and that are incapable are being applied to study the assembly of empty viral of metabolic activity. Instead, after viruses infect cells, capsids, then focus on the role of genome molecules Triangulation numbers Classification system, they alter cellular molecular machinery so that it pro- (RNA/DNA) during assembly, followed by a discussion developed by Caspar and duces new viruses, which are then released into the envi- of studies of the steady-state dynamics of assembled Klug, for icosahedral viruses. ronment. This sequence of events, the viral life cycle, is viruses. BOx 2 summarizes several experimental tech- T-numbers are integers and schematically discussed in BOx 1. -

DNA Could Trap Viruses Irfan* Department of Microbiology, King Saud University, Saudi Arabia

& Bioch ial em OPEN ACCESS Freely available online b ic ro a c l i T M e f c h o n l o a Journal of n l o r g u y o J ISSN: 1948-5948 Microbial & Biochemical Technology Short Communication DNA could trap viruses Irfan* Department of Microbiology, King Saud University, Saudi Arabia INTRODUCTION also be used as a type of "virus trap." If they we have a tendency tore to be coated with virus-binding molecules at the inside, they have To date, there aren't any powerful antidotes towards maximum to be prepared to bind viruses tightly and consequently be capable virus infections. Scientists have now evolved a brand new approach: of take them out of circulation. For this, however, the hole our they engulf and neutralize viruses with nano-pills tailor-made from bodies might even should very own sufficiently large openings thru genetic cloth the use of the DNA origami method. The approach that viruses gets into the shells. has already been examined towards hepatitis and adeno-related viruses in mobileular cultures. It might also show a hit towards "None of the gadgets that we had engineered victimization corona viruses. deoxyribonucleic acid artwork generation at that factor might were prepared to engulf a whole virus -- they had been simply too small," There are antibiotics towards risky bacteria, but few antidotes to deal with acute infectious agent infections. Some infections can says Hendrik Dietz in retrospect. "Building solid hole our bodies of be averted via way of means of vaccination however growing new this length changed into a huge challenge. -

Abstracts of Special Session Presentations Biology of Plant Pathogens

Abstracts of Special Session Presentations Biology of Plant Pathogens Aquatic Plant Pathology Development of an indigenous pathogen for management of the submersed freshwater macrophyte Hydrilla verticillata. J. F. SHEARER. Fungal pathogens: Their role in the ecology of floating and submerged U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Research and Development Center, freshwater plants. R. CHARUDATTAN. Plant Pathology Dept., University Vicksburg, MS. Phytopathology 95:S120. Publication no. P-2005-0003-SSA. of Florida, Gainesville, FL. Phytopathology 95:S120. Publication no. P-2005- Hydrilla verticillata 0001-SSA. (L.f.) Royle (hydrilla) is considered one of the three most important aquatic weeds in the world. Plant infestations can impede navi- Freshwater plants encompass a diverse group of morphologically and gation, clog drainage or irrigation canals, affect water intake systems, interfere taxonomically dissimilar plants adapted to life in a highly unstable habitat. with recreational activities, and disrupt wildlife habitats. The plant is an These plants can be emergent and free-floating, emergent and rooted, fully excellent competitor in aquatic habitats because it can photosynthesize at low submerged and free-floating, or fully submerged and rooted. A variety of light levels, has wide environmental tolerances, and produces several types of fungi in the Oomycota, Chytridiomycota, Anamorphic fungi, Ascomycota, extended survival propagules. The indigenous fungal pathogen, Mycolepto- and Basidiomycota cause diseases on these plants. While pathogenic fungi can discus terrestris (Gerd.) Ostazeski, (Mt) has shown significant potential for regulate plant population density by limiting plant growth and seedling use as a bioherbicide for management of hydrilla. Liquid fermentation recruitment, opportunistic parasites accelerate senescence of older growth and methods have been developed and patented that yield stable, effective recycle nutrients from dead tissues. -

Symposium to Honor Eminent FSU Scientist Florida State University News FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY NEWS the OFFICIAL NEWS SOURCE of FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY

1/9/2017 Symposium to honor eminent FSU scientist Florida State University News FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY NEWS THE OFFICIAL NEWS SOURCE OF FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY Symposium to honor eminent FSU scientist BY: KATHLEEN HAUGHNEY (MAILTO:[email protected]) | PUBLISHED: JANUARY 5, 2017 (HTTP://NEWS.FSU.EDU/NEWS/SCIENCE‑TECHNOLOGY/2017/01/05/SYMPOSIUM‑ HONOR‑EMINENT‑FSU‑SCIENTIST/) | 1:34 PM | SHARE: A symposium to honor a retired Florida State professor who made major contributions to the world of structural biology is attracting an unprecedented number of members of the National Academy of Sciences to Tallahassee. The Caspar Structural Biology Symposium, to be held Jan. 7‑8 at Florida State University, honors Donald Caspar, professor emeritus of biological science at Florida State, who will also turn 90 during the symposium. “Don Caspar is a legend in the structural biology field,” said Piotr Fajer, director of the Institute of Molecular Biophysics at Florida State. “All of these people coming here is a tribute to him.” The event features 15 members of the National Academy of Sciences who will discuss the latest developments in the field and technologies such as Donald Caspar, professor emeritus of biological science at Florida State x‑ray crystallography and electron microscopy. “I don’t think there’s been a conference that attracted this many academy members to Tallahassee before,” Fajer said. FSU Professor of Biophysics Kenneth Taylor, who uses electron microscopy to study the tiniest muscle filaments in the body, will also be among the speakers. Andrew Brown, author of a biography on J.D. Bernal, a pioneer in x‑ray crystallography in structural biology, will wrap up the symposium with a talk on Sunday. -

From Tobacco Mosaic Virus Pests to Enzymatically Active Assemblies

Novel roles for well-known players: from tobacco mosaic virus pests to enzymatically active assemblies Claudia Koch1, Fabian J. Eber1, Carlos Azucena2, Alexander Förste3, Stefan Walheim3, Thomas Schimmel3, Alexander M. Bittner4, Holger Jeske1, Hartmut Gliemann2, Sabine Eiben1, Fania C. Geiger1 and Christina Wege*1 Review Open Access Address: Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 2016, 7, 613–629. 1Institute of Biomaterials and Biomolecular Systems, Department of doi:10.3762/bjnano.7.54 Molecular Biology and Plant Virology, University of Stuttgart, Pfaffenwaldring 57, Stuttgart, D-70550, Germany, 2Institute of Received: 09 February 2016 Functional Interfaces (IFG), Chemistry of Oxidic and Organic Accepted: 03 April 2016 Interfaces, Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT), Published: 25 April 2016 Hermann-von-Helmholtz-Platz 1, Eggenstein-Leopoldshafen, Karlsruhe, D-76344, Germany, 3Institute of Nanotechnology (INT) and This article is part of the Thematic Series "Functional nanostructures – Karlsruhe Institute of Applied Physics (IAP) and Center for Functional biofunctional nanostructures and surfaces". Nanostructures (CFN), Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT), INT: Hermann-von-Helmholtz-Platz 1, Eggenstein-Leopoldshafen, Associate Editor: K. Koch D-76344, Germany, and IAP/CFN: Wolfgang-Gaede-Straße 1, Karlsruhe, D-76131 Germany and 4CIC Nanogune, Tolosa Hiribidea © 2016 Koch et al; licensee Beilstein-Institut. 76, E-20018 Donostia-San Sebastián, Spain, and Ikerbasque, Maria License and terms: see end of document. Díaz de Haro 3, E-48013 Bilbao, Spain Email: Christina Wege* - [email protected] * Corresponding author Keywords: biotemplate; enzyme biosensor; nanotechnology; tobacco mosaic virus; virus-like particles Abstract The rod-shaped nanoparticles of the widespread plant pathogen tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) have been a matter of intense debates and cutting-edge research for more than a hundred years. -

Student Handbook 2015-2016

MOLECULAR BIOPHYSICS GRADUATE PROGRAM Florida State University Image from the lab of Dr. Wei Yang STUDENT HANDBOOK 2015-2016 Cover illustration courtesy of Dr. Wei Yang and Dr. Donald LD Caspar. The Yang lab in collaboration with Donald Caspar uses advanced simulation techniques to look at the assembly mechanism of the coat proteins of the Tobacco Mosaic virus. 2 MOLECULAR BIOPHYSICS GRADUATE PROGRAM FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY PHILOSOPHY The Graduate Program in Molecular Biophysics is designed to transform an indi- vidual from student to professional scholar. Awarding of the degree signifies that the individual is qualified to join the community of scholars and is recognized as an authority in the discipline. Graduate education is one of the most important mis- sions of this program. Every effort is made to provide both financial and profes- sional support for qualified graduate students. The goal of such support is to facili- tate progress toward the degree while contributing to the teaching and research effort of the University. This handbook contains information useful to both graduate students and faculty. It is important to point out two significant and sometimes interactive features. They are rather standard academic practices and are not unique to our program: 1. Generally, students complete the requirements in the MOB Student Hand- book dated the year in which they enter the program, or those of any subse- quent year’s Handbook, but may not combine requirements from different years except at the discretion of the MOB Program Committee, and then only for sound academic reasons presented in advance. Continuing students who are unsure of their requirements should consult the MOB Graduate Office. -

Physics of RNA and Viral Assembly

Eur. Phys. J. E 19, 303{310 (2006) THE EUROPEAN DOI 10.1140/epje/i2005-10071-1 PHYSICAL JOURNAL E Physics of RNA and viral assembly R.F. Bruinsmaa Department of Physics and Astronomy, The University of California at Los Angeles, Los Angeles 90049, CA, USA Received 11 August 2005 / Published online: 23 March 2006 { °c EDP Sciences / Societ`a Italiana di Fisica / Springer-Verlag 2006 Abstract. The overview discusses the application of physical arguments to structure and function of single- stranded viral RNA genomes. PACS. 87.15.Nn Properties of solutions; aggregation and crystallization of macromolecules { 61.50.Ah Theory of crystal structure, crystal symmetry; calculations and modeling { 81.16.Dn Self-assembly The other contributions to this Focus Point discuss how physical descriptions of DNA and RNA can illumi- nate our understanding of cell functioning. Here, the fo- cus will be on dysfunctional nucleic acids, speci¯cally the genomes of infectious viruses. A virus is a shadowy citizen of a borderland between living and dead matter; a par- asite that reproduces only in the environment of a host cell, in fact by the mobilization of the macromolecular machinery of the host. A virus also does not carry out any metabolic activity, which means that, unlike living cells, it e®ectively is in a state of thermal equilibrium with its environment; one reason why physics |and statistical Fig. 1. Image reconstruction of the MS2 virus, viewed along physics in particular| can be a useful tool. Another rea- a 5-fold icosahedral symmetry axis. From reference [2]. son is apparent from an image reconstruction of a virus. -

A Survival Guide to the Misinformation Age: Scientific Habits of Mind by David J

Crystallography Newsletter Volume 9, No. 1, January 2017 Rigaku Oxford Diffraction European User's Meeting In this issue: European User's Meeting Rigaku X-ray forum Crystallography in the news Survey of the month Last month's survey Product spotlight Videos of the month Lab in the spotlight Useful link Upcoming events Recent crystallographic papers Book review The 2017 European User's Meeting will be held within Merton College of the University of Oxford on 22nd to 23rd of March. The meeting will be a great opportunity to join us to Rigaku Oxford Diffraction discover the latest developments at Rigaku Oxford Diffraction and also hear from the user invites all users of Rigaku equipment community about their experiences with their Single Crystal Diffraction systems. to join us on our X-ray forum The meeting will have a workshop focus where the latest tips and tricks within CrysAlisPro will be discussed. There will also be a session covering Olex2 which will include examples of how to solve and refine advanced structures. Finally, there will be a feedback session for those of you wishing to stay, where you may promote your ideas to members of Rigaku Oxford Diffraction. To reserve your place, e-mail [email protected] Crystallography in the news January 2, 2017. In research conducted at SACLA, Japan's XFEL (X-ray free electron laser) facility, membrane protein folding has been captured for the first time in 3D and at a single-atom level. Lead author Eriko Nango of Kyoto University explains that, whereas www.rigakuxrayforum.com conventional X-ray crystallography only captures static protein structures, SACLA has enabled the team to observe minute changes in protein structures during transformation. -

Discovering the Secrets of Life: a Summary Report on the Archive For

Discovering the Secrets of Life A Summary Report on the Archive for the History of Molecular Biology By Jeremy M. Norman ©April 15, 2002 The story opens in 1936 when I left my hometown, Vienna, for Cambridge, England, to seek the Great Sage. He was an Irish Catholic converted to Communism, a mineralogist who had turned to X-ray crystallography: J. D. Bernal. I asked the Great Sage: “How can I solve the secret of life?” He replied: “The secret of life lies in the structure of proteins, and there is only one way of solving it and that is by X-ray crystallography.” Max Perutz, 1997, xvii. 2 Contents 1. Introduction 1.1 The Scope and Condition of this Archive 1.2. A Unique Achievement in the History of Private Collecting of Science 1.3 My Experience with Manuscripts in the History of Science 1.4 Limited Availability of Major Scientific Manuscripts: Newton, Einstein, and Darwin 1.5 Discovering How Natural Selection Operates at the Molecular Level 1.6 Collecting the Last Great Scientific Revolution before Email 1.7. Exploring New Fields of Science Collecting 1.8 My Current Working Outline for a Summary Book on the Archive 2.Foundations for a Revolution in Biology The Quest for the Secret of Life 3. Discovering ”The First Secret of Life” The Structure of DNA and its Means of Replication 4. Discovering the Structure of RNA and the Tobacco Mosaic Virus 5. Deciphering the Genetic Code, ”the Dictionary Relating the Nucleic Acid Language to the Protein Language” 6. The Rosalind Franklin Archive 7. -

Herbert Rees Wilson on a Circular Plaque Just Inside the Main

Herbert Rees Wilson On a circular plaque just inside the main entrance to King’s College on the Strand in London there are the names of five scientists and the inscription says “DNA X-ray diffraction studies 1953”. One of these names is that of Herbert Rees Wilson who was born on 28th January 1929 on his grandfather's farm in Nefyn on the Llyn peninsula in north Wales. His father, Thomas, was a ship's captain, and his mother Jennie was staying with her parents because her husband was away at sea for long periods. When Herbert's brother John was born, the family moved into their own house, Summer Hill, in the town. Herbert was educated at Nefyn school, Pwllheli Grammar School and UCNW (University College of North Wales) Bangor, where he was awarded a first class honours BSc in Physics in 1949, and a PhD in 1952. His PhD work involved using X-ray diffraction techniques under the supervision of Prof. Edwin A. Owen, the title of his thesis being the Effect of cold-work on metals at ordinary temperatures. As he neared the end of his PhD, Herbert wondered what he might do next, and to quote him directly he was 'keen to change from solid-state physics to biophysics'. He took advice from his supervisor and, after a number of interviews and discussions, joined Maurice Wilkins in 1952 to work on X-ray diffraction studies of DNA at King's College in London. This group provided much of the evidence that led Francis Crick and James Watson to postulate their now-famous double-helix structure for deoxyribose nucleic acid (DNA), making their crucial contribution to our understanding of the transmission of genetic information.