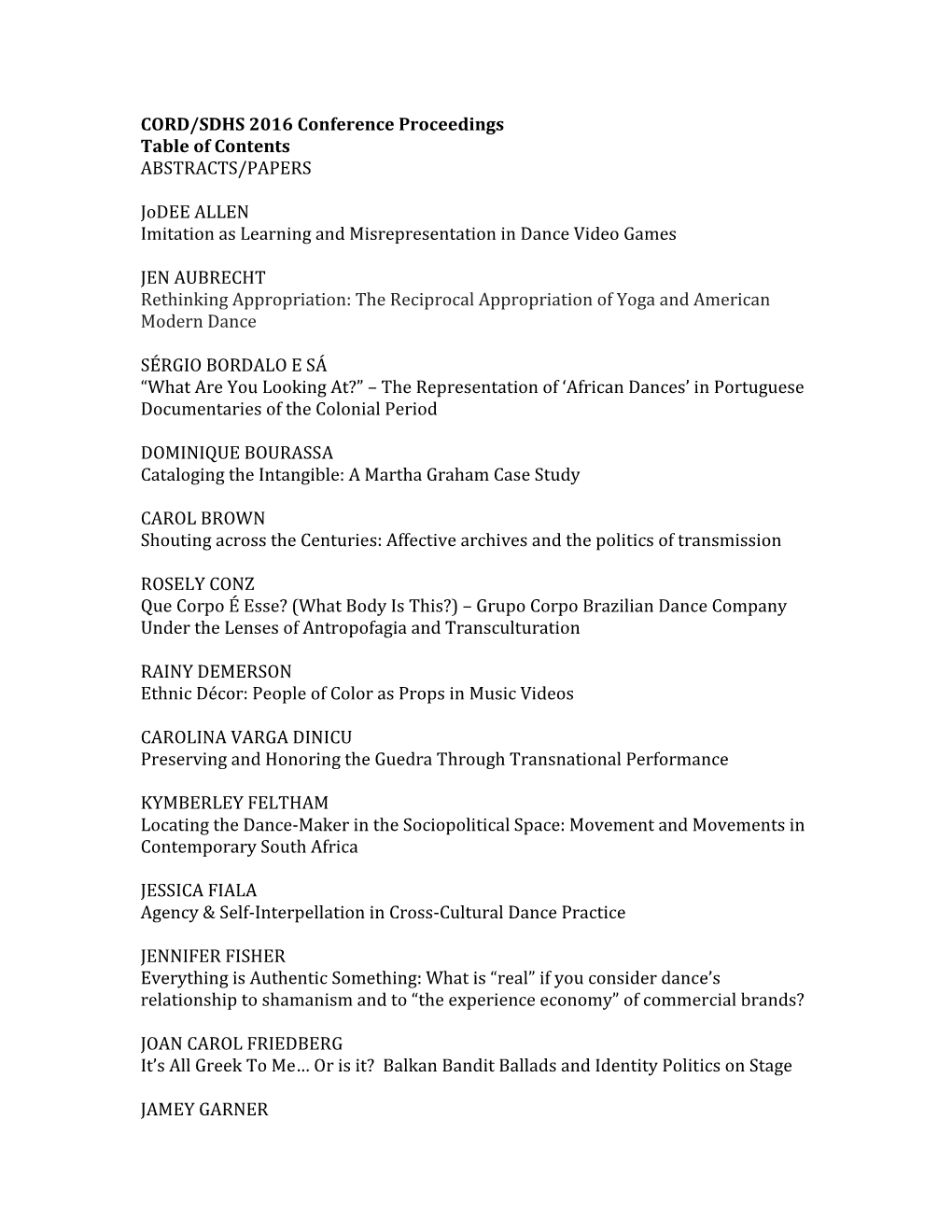

CORD/SDHS 2016 Conference Proceedings Table of Contents ABSTRACTS/PAPERS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World Conference on Higher Education

World Conference on Higher Education Higher Education in the Twenty-first Century Vision and Action UNESCO Paris 5–9 October 1998 Volume I Final Report 5WOOCT[QH major concerns of higher education. Special VJG9QTNF&GENCTCVKQPQP attention should be paid to higher education's role of service to society, especially activities aimed at *KIJGT'FWECVKQP eliminating poverty, intolerance, violence, illiteracy, hunger, environmental degradation and disease, and to activities aiming at the development of peace, through an interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary 1. Higher education shall be equally accessible approach. to all on the basis of merit, in keeping with Article 5. Higher education is part of a seamless system, 26.1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. starting with early childhood and primary education As a consequence, no discrimination can be and continuing through life. The contribution of accepted in granting access to higher education on higher education to the development of the whole grounds of race, gender, language, religion or education system and the reordering of its links economic, cultural or social distinctions, or physical with all levels of education, in particular with disabilities. secondary education, should be a priority. 2. The core missions of higher education Secondary education should both prepare for and systems (to educate, to train, to undertake research facilitate access to higher education as well as offer and, in particular, to contribute to the sustainable broad training and prepare students for active life. development and improvement of society as a 6. Diversifying higher education models and whole) should be preserved, reinforced and further recruitment methods and criteria is essential both to expanded, namely to educate highly qualified meet demand and to give students the rigorous graduates and responsible citizens and to provide background and training required by the twenty-first opportunities (espaces ouverts) for higher learning century. -

Sia THIS IS ACTING ALBUM PRESS RELEASE November 5, 2015

SIA TO RELEASE NEW ALBUM THIS IS ACTING ON JANUARY 29, 2016 SIA PREMIERES VIDEO TODAY FOR “ALIVE” ON VEVO CLICK HERE TO WATCH “ALIVE” FANS WHO PRE-ORDER THIS IS ACTING RECEIVE “ALIVE” AND NEW SONG “BIRD SET FREE” TODAY CLICK HERE TO LISTEN TO “BIRD SET FREE” SIA TO PERFORM ON “SATURDAY NIGHT LIVE” THIS SATURDAY, NOVEMBER 7TH ! (New York-November 5, 2015) Singer/songwriter/producer/massive hitmaker Sia today announces that her album THIS IS ACTING will be released everywhere on January 29, 2016 (Monkey Puzzle Records/RCA Records). Sia revealed cover art and album release date for THIS IS ACTING via her new Instagram account earlier this week. In celebration of her album pre-order going live, Sia premieres her video for “Alive” on Vevo. Fans who pre-order THIS IS ACTING will receive “Alive” and new track “Bird Set Free” instantly. Click here to watch the video for “Alive.” Click here to listen to “Bird Set Free.” Sia will be performing “Alive” and “Bird Set Free” on “Saturday Night Live” on November 7th. The video for “Alive” stars 9 year old child actress/dancer Mahiro Takano and was filmed in Chiba, Japan. The video was directed by Sia and Daniel Askill, the same creative team behind the videos for “Chandelier,” “Elastic Heart” and “Big Girls Cry.” In addition to Jessie Shatkin who produced “Alive,” Sia also worked with longtime collaborator/producer Greg Kurstin on THIS IS ACTING. “Alive,” the album’s first single was written by Sia, Adele and Tobias Jesso, Jr. and was produced by Jesse Shatkin, who also co-wrote and co-produced Sia’s massive four-time Grammy nominated “Chandelier.” Sia released her #1 charting, critically-acclaimed, and gold-certified album 1000 FORMS OF FEAR (Monkey Puzzle Records/RCA Records) last year in July, which features her massive breakthrough singles “Chandelier” and “Elastic Heart.” The groundbreaking video for “Chandelier” has enjoyed an unprecedented 965 million views and its follow-up video “Elastic Heart” with over 436 million views. -

Xbox 360 Total Size (GB) 0 # of Items 0

Done In this Category Xbox 360 Total Size (GB) 0 # of items 0 "X" Title Date Added 0 Day Attack on Earth July--2012 0-D Beat Drop July--2012 1942 Joint Strike July--2012 3 on 3 NHL Arcade July--2012 3D Ultra Mini Golf July--2012 3D Ultra Mini Golf Adventures 2 July--2012 50 Cent: Blood on the Sand July--2012 A World of Keflings July--2012 Ace Combat 6: Fires of Liberation July--2012 Ace Combat: Assault Horizon July--2012 Aces of Galaxy Aug--2012 Adidas miCoach (2 Discs) Aug--2012 Adrenaline Misfits Aug--2012 Aegis Wings Aug--2012 Afro Samurai July--2012 After Burner: Climax Aug--2012 Age of Booty Aug--2012 Air Conflicts: Pacific Carriers Oct--2012 Air Conflicts: Secret Wars Dec--2012 Akai Katana July--2012 Alan Wake July--2012 Alan Wake's American Nightmare Aug--2012 Alice Madness Returns July--2012 Alien Breed 1: Evolution Aug--2012 Alien Breed 2: Assault Aug--2012 Alien Breed 3: Descent Aug--2012 Alien Hominid Sept--2012 Alien vs. Predator Aug--2012 Aliens: Colonial Marines Feb--2013 All Zombies Must Die Sept--2012 Alone in the Dark Aug--2012 Alpha Protocol July--2012 Altered Beast Sept--2012 Alvin and the Chipmunks: Chipwrecked July--2012 America's Army: True Soldiers Aug--2012 Amped 3 Oct--2012 Amy Sept--2012 Anarchy Reigns July--2012 Ancients of Ooga Sept--2012 Angry Birds Trilogy Sept--2012 Anomaly Warzone Earth Oct--2012 Apache: Air Assault July--2012 Apples to Apples Oct--2012 Aqua Oct--2012 Arcana Heart 3 July--2012 Arcania Gothica July--2012 Are You Smarter that a 5th Grader July--2012 Arkadian Warriors Oct--2012 Arkanoid Live -

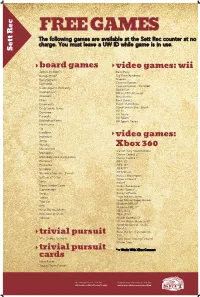

Sett Rec Counter at No Charge

FREE GAMES The following games are available at the Sett Rec counter at no charge. You must leave a UW ID while game is in use. Sett Rec board games video games: wii Apples to Apples Bash Party Backgammon Big Brain Academy Bananagrams Degree Buzzword Carnival Games Carnival Games - MiniGolf Cards Against Humanity Mario Kart Catchphrase MX vs ATV Untamed Checkers Ninja Reflex Chess Rock Band 2 Cineplexity Super Mario Bros. Crazy Snake Game Super Smash Bros. Brawl Wii Fit Dominoes Wii Music Eurorails Wii Sports Exploding Kittens Wii Sports Resort Finish Lines Go Headbanz Imperium video games: Jenga Malarky Mastermind Xbox 360 Call of Duty: World at War Monopoly Dance Central 2* Monopoly Deal (card game) Dance Central 3* Pictionary FIFA 15* Po-Ke-No FIFA 16* Scrabble FIFA 17* Scramble Squares - Parrots FIFA Street Forza 2 Motorsport Settlers of Catan Gears of War 2 Sorry Halo 4 Super Jumbo Cards Kinect Adventures* Superfection Kinect Sports* Swap Kung Fu Panda Taboo Lego Indiana Jones Toss Up Lego Marvel Super Heroes Madden NFL 09 Uno Madden NFL 17* What Do You Meme NBA 2K13 Win, Lose or Draw NBA 2K16* Yahtzee NCAA Football 09 NCAA March Madness 07 Need for Speed - Rivals Portal 2 Ruse the Art of Deception trivial pursuit SSX 90's, Genus, Genus 5 Tony Hawk Proving Ground Winter Stars* trivial pursuit * = Works With XBox Connect cards Harry Potter Young Players Edition Upcoming Events in The Sett Program your own event at The Sett union.wisc.edu/sett-events.aspx union.wisc.edu/eventservices.htm. -

Dance Photograph Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf8q2nb58d No online items Guide to the Dance Photograph Collection Processed by Emma Kheradyar. Special Collections and Archives The UCI Libraries P.O. Box 19557 University of California Irvine, California 92623-9557 Phone: (949) 824-3947 Fax: (949) 824-2472 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.lib.uci.edu/rrsc/speccoll.html © 1997 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Guide to the Dance Photograph MS-P021 1 Collection Guide to the Dance Photograph Collection Collection number: MS-P021 Special Collections and Archives The UCI Libraries University of California Irvine, California Contact Information Special Collections and Archives The UCI Libraries P.O. Box 19557 University of California Irvine, California 92623-9557 Phone: (949) 824-3947 Fax: (949) 824-2472 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.lib.uci.edu/rrsc/speccoll.html Processed by: Emma Kheradyar Date Completed: July 1997 Encoded by: James Ryan © 1997 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Dance Photograph Collection, Date (inclusive): 1906-1970 Collection number: MS-P021 Extent: Number of containers: 5 document boxes Linear feet: 2 Repository: University of California, Irvine. Library. Dept. of Special Collections Irvine, California 92623-9557 Abstract: The Dance Photograph Collection is comprised of publicity images, taken by commercial photographers and stamped with credit lines. Items date from 1906 to 1970. The images, all silver gelatin, document the repertoires of six major companies; choreographers' original works, primarily in modern and post-modern dance; and individual, internationally known dancers in some of their significant roles. -

Game Console Rating

Highland Township Public Library - Video Game Collection Updated January 2020 Game Console Rating Abzu PS4, XboxOne E Ace Combat 7: Skies Unknown PS4, XboxOne T AC/DC Rockband Wii T Age of Wonders: Planetfall PS4, XboxOne T All-Stars Battle Royale PS3 T Angry Birds Trilogy PS3 E Animal Crossing, City Folk Wii E Ape Escape 2 PS2 E Ape Escape 3 PS2 E Atari Anthology PS2 E Atelier Ayesha: The Alchemist of Dusk PS3 T Atelier Sophie: Alchemist of the Mysterious Book PS4 T Banjo Kazooie- Nuts and Bolts Xbox 360 E10+ Batman: Arkham Asylum PS3 T Batman: Arkham City PS3 T Batman: Arkham Origins PS3, Xbox 360 16+ Battalion Wars 2 Wii T Battle Chasers: Nightwar PS4, XboxOne T Beyond Good & Evil PS2 T Big Beach Sports Wii E Bit Trip Complete Wii E Bladestorm: The Hundred Years' War PS3, Xbox 360 T Bloodstained Ritual of the Night PS4, XboxOne T Blue Dragon Xbox 360 T Blur PS3, Xbox 360 T Boom Blox Wii E Brave PS3, Xbox 360 E10+ Cabela's Big Game Hunter PS2 T Call of Duty 3 Wii T Captain America, Super Soldier PS3 T Crash Bandicoot N Sane Trilogy PS4 E10+ Crew 2 PS4, XboxOne T Dance Central 3 Xbox 360 T De Blob 2 Xbox 360 E Dead Cells PS4 T Deadly Creatures Wii T Deca Sports 3 Wii E Deformers: Ready at Dawn PS4, XboxOne E10+ Destiny PS3, Xbox 360 T Destiny 2 PS4, XboxOne T Dirt 4 PS4, XboxOne T Dirt Rally 2.0 PS4, XboxOne E Donkey Kong Country Returns Wii E Don't Starve Mega Pack PS4, XboxOne T Dragon Quest 11 PS4 T Highland Township Public Library - Video Game Collection Updated January 2020 Game Console Rating Dragon Quest Builders PS4 E10+ Dragon -

02 Hauptdokument / PDF, 9355 KB

III-755-BR/2021 der Beilagen - Bericht - 02 Hauptdokument 1 von 245 Kunst Kultur Bericht www.parlament.gv.at 2 von 245 III-755-BR/2021 der Beilagen - Bericht - 02 Hauptdokument www.parlament.gv.at Kunst- und Kulturbericht 2020 III-755-BR/2021 der Beilagen - Bericht 02 Hauptdokument www.parlament.gv.at 3 von 245 4 von 245 Kunst- und Kulturbericht 2020 III-755-BR/2021 der Beilagen - Bericht 02 Hauptdokument www.parlament.gv.at Wien 2021 Liebe Leserinnen und Leser, III-755-BR/2021 der Beilagen - Bericht 02 Hauptdokument als wir im Juli des vergangenen Jahres den Kunst- und Kulturbericht 2019 veröffent- lichten, hatten wir gehofft, dass die optimistischen Prognosen über den Verlauf und die www.parlament.gv.at Eindämmung der Pandemie eintreten werden und wir Anfang des Jahres 2021 unser gesellschaftliches und kulturelles Leben langsam wieder aufnehmen können. Es kam anders. Das Virus und seine Mutanten haben es nicht erlaubt, dass wir uns ohne er- hebliche Gefahr für unsere Gesundheit in größeren Gruppen treffen oder als Publikum versammeln. Diese unsichtbaren Gegner haben es unmöglich gemacht, in Theatern, Kinos, Konzerthäusern, Galerien und Museen zusammenzukommen, um das zu tun, was wir alle lieben: gemeinsam Kunst zu erleben und zu genießen. Unser wichtigstes Ziel war es daher, alles zu unternehmen, damit wir am Ende der Pan- demie dort fortsetzen können, wo wir plötzlich und unerwartet aus unserem kulturellen Leben gerissen wurden: All jene, die in unserem Land Kunst machen, die sich dazu entschlossen haben, ihr Leben und ihre ganze Kraft dem künstlerischen Schaffen zu widmen, sollten bestmöglich durch diese schwierigen Zeiten kommen. -

128901439.Pdf

the carillon The University of Regina Students’ Newspaper since 1962 Mar. 7 - 13, 2013 | Volume 55, Issue 22 | carillonregina.com cover The City of Regina has been on the staff a relentless revitalization project for the past few years, in other editor-in-chief dietrich neu [email protected] words, screwing up everything. business manager shaadie musleh The latest project laden with [email protected] production manager julia dima controversy is the demolition [email protected] copy editor michelle jones and rebuilding of Connaught [email protected] elementary school. Read about news editor taouba khelifa [email protected] the plans on page 6. And you a&c editor paul bogdan [email protected] have a lovely day. sports editor autumn mcdowell [email protected] op-ed editor edward dodd [email protected] visual editor arthur ward [email protected] ad manager neil adams [email protected] news arts & culture technical coordinator jonathan hamelin [email protected] news writer kristen mcewen sophie long a&c writer kyle leitch sports writer braden dupuis photographers olivia mason marc messett tenielle bogdan emily wright Growing together. 4 Con-no more. 6 Regina’s Seedy Saturday Continuing Regina's heritage contributors this week regan meloche joel blechinger jordan palmer brought together experts, gar- of tearing down its heritage, michael chmielewski paige kreutzwieser kevin chow deners, local business owners, the Board of Education voted and organizations, all looking to tear down and rebuild the forward to the start of spring 100 year old Connaught the paper and the planting season. School despite outcry from THE CARILLON BOARD OF DIRECTORS Gardening is more than just the community. -

January 2, 2020 Kirin J. Callinan Drops the World's First, And

January 2, 2019 For Immediate Release Kirin J. Callinan Drops The World’s First, and Arguably Greatest Music Video of the 2020s For “The Homosexual” WATCH HERE Co-Produced The Voidz New Single with Mac DeMarco, Performed as Master of Ceremony for The Strokes NYE Show At Barclays Stadium To start the new decade just as he ended the last, Kirin J Callinan’s unique, singular talent comes to the fore again via the grand and sumptuous music video for his strangely autobiographical cover version of the underground Momus classic “The Homosexual,” lifted from his third studio album, Return To Center, out now on Terrible Records. Directed by Michael Hili and conceptualized by Kirin, the video dropped as the clock striked midnight on NYE, making it the first video released in the world this decade. The crushing hand of time will decide if it remains the greatest! On New Year’s Eve Callinan shared the 20,000 seater Barclay stage in New York alongside The Strokes and Mac Demarco. Kirin, Mac and Julian Casablancas also recently colluded to produce the latest single ‘Did My Best’ for ‘The Voidz’. Earlier this month,Callinan has been filming the lead role in the debut feature film for acclaimed commercial director Daniel Askill. Askill directed the Grammy-nominated videos with Sia for ‘Chandelier’ and ‘Elastic Heart’. He’s also been a strong contender on many best of decades list for his last album of original material, Bravado, and it’s meme-able single “Big Enough”. UNESCO in their review of biggest moments of culture and science of the decade compiled a list of the greatest albums released in the world this past decade and they included Kirin J Callinan’s Bravado in their 2010's time capsule – see HERE. -

Sång Inom Populärmusikgenrer Daniel Zangger Borch Zangger Daniel Populärmusikgenrer Inom Sång

2008:59 DOKTORSAVHANDLING Sång inom populärmusikgenrer Daniel Zangger Borch Sång inom populärmusikgenrer Daniel Zangger Borch Luleå tekniska universitet 2008:59 Musikhögskolan i Piteå Universitetstryckeriet, Luleå 2008:59|: 02-544|: - -- 08 ⁄59 -- Sång inom Populärmusikgenrer Konstnärliga, fysiologiska och pedagogiska aspekter Daniel Zangger Borch Distribution Institutionen för musik och medier/Luleå tekniska universitet Box 744 941 28 Piteå Telefon: 0911-72600 Fax: 0911-72610 Publicerad elektroniskt på http://epubl.ltu.se ISSN: 1402-1544 ISRN: LTU-DT – 08/59 – SE © Daniel Zangger Borch 2008 Abstract This dissertation consists of five parts dealing with three areas: voice science, voice pedagogics and musical expression. The overall aim was to contribute to a scientific basis for improved singing technique within genres of popular music. Scientific analyses of vocal expression are used as a complement to a vocal teaching method that is suitable for the vocal ideals used in the popular music genres, considering also current scientific knowledge in the areas of physiology, acoustics and rehabilitation. Part I analyzes a classically trained singer’s voice and some frequently used types of accompaniments as well as the voices of five popular music singers. The results suggested that boosting the frequency range 3500 Hz in the popular music singer’s monitor system could be beneficial. Part II analyzed how the vocal “dist” ornament, commonly used by rock singers, is generated in my rock singer’s voice. A high-speed video recording combined with simultaneous voice source analysis revealed that this ornament was produced by adducting the supraglottal structures such that they were brought to vibration by the airstream. -

Audio Streams up 15%, Vinyl Sales Double in First Half of 2021

Bulletin YOUR DAILY ENTERTAINMENT NEWS UPDATE JULY 14, 2021 Page 1 of 18 INSIDE Audio Streams Up 15%, Vinyl Sales • Walter Kolm’s WK Double in First Half of 2021 Records Expands, Hires New CEO and BY ED CHRISTMAN Launches Mexican Imprint As the pandemic ends, the recorded music business million streams. (By comparison, Roddy Ricch’s “The has continued to thrive: overall on-demand streams in Box” had been streamed 1.07 billion times during the • Venues Won’t Have to Reapply the U.S. grew 10.8%, to 555.3 billion, in the first half of first half of last year.) for Supplemental 2021 compared to the same period of 2020, according The top album is Morgan Wallen’s Dangerous: The Shuttered Venue to MRC Data. Within that audio streams grew 15% to Double Album, with 2.1 million album consumption Grants nearly 483 billion from nearly 420 million in the cor- units, outpacing the No. 2 title, Olivia Rodrigo’s SOUR, • Why Picking a responding earlier period and globally audio streams at 1.37 million units. Wallen’s album is also outper- New Britney Spears performed even better jumping a whopping 27.3% to forming last year’s mid-year No. 1, Lil Baby’s My Turn, Conservatorship 1.296 trillion. which had nearly 1.5 million album consumption units Lawyer Isn’t So Not all the good news is digital. Vinyl sales, which by this time. Simple have grown for the past decade, more than doubled Taylor Swift’s evermore leads vinyl sales over the • 2021 Billboard Latin between January and June, up 108.2% to 19.2 million period, with 143,000 units sold, followed by Harry Music Awards Date & from 9.2 million in the first six months of last year. -

The Crack of the Bat 7

City Employees Club of Los Angeles • Alive! APRIL 2015 35 Public Works Los Angeles Public Library Photos by Dalila Vielma, Club Counselor Library’s 35 Goodbye, Charlie Charlie Mims retires as Chief Construction Inspector after 47 years of City service. TOP riends, family and coworkers threw Fa retirement dinner and reception Feb. 7 for Charlie Mims, Chief Construction Inspector, Public Works/Contract Administration. 10 The event was held at the J.W. Marriott at L.A. Live. Here’s what LA was Charlie began his career at the DWP as reading, watching and part of survey crew and then as construc- listening to in February. tion inspector of the Second Los Angeles Aqueduct Program. Lists are courtesy Los Angeles He went to school at UC Santa Cruz Public Library, Central library and them went to work at Public Works/ downtown and 72 branches Contract Administration in 1970. He was combined. promoted from Construction Inspector to Chief Construction Inspector, and then headed the Valley’s Wastewater, Environmental Projects and Metropolitan Construction Divisions for 29 years. Books loaned: Charlie worked on various projects, 1. The Burning Room, including the rebuilding of the Hyperion Michael Connelly Treatment Plant; the Echo Park Lake reno- Gone Girl, Gillian Flynn vation projects in 1984 and 2012; the $80 2. million Zoo construction program; and 3. The Fault in Our Stars, John Green many others that have benefitted the 4. Personal, Lee Child people of Los Angeles. 5. The Maze Runner, James Dashner He served as commissioner on Los 6. Divergent, Veronica Roth Angeles City Employees Retirement 7.