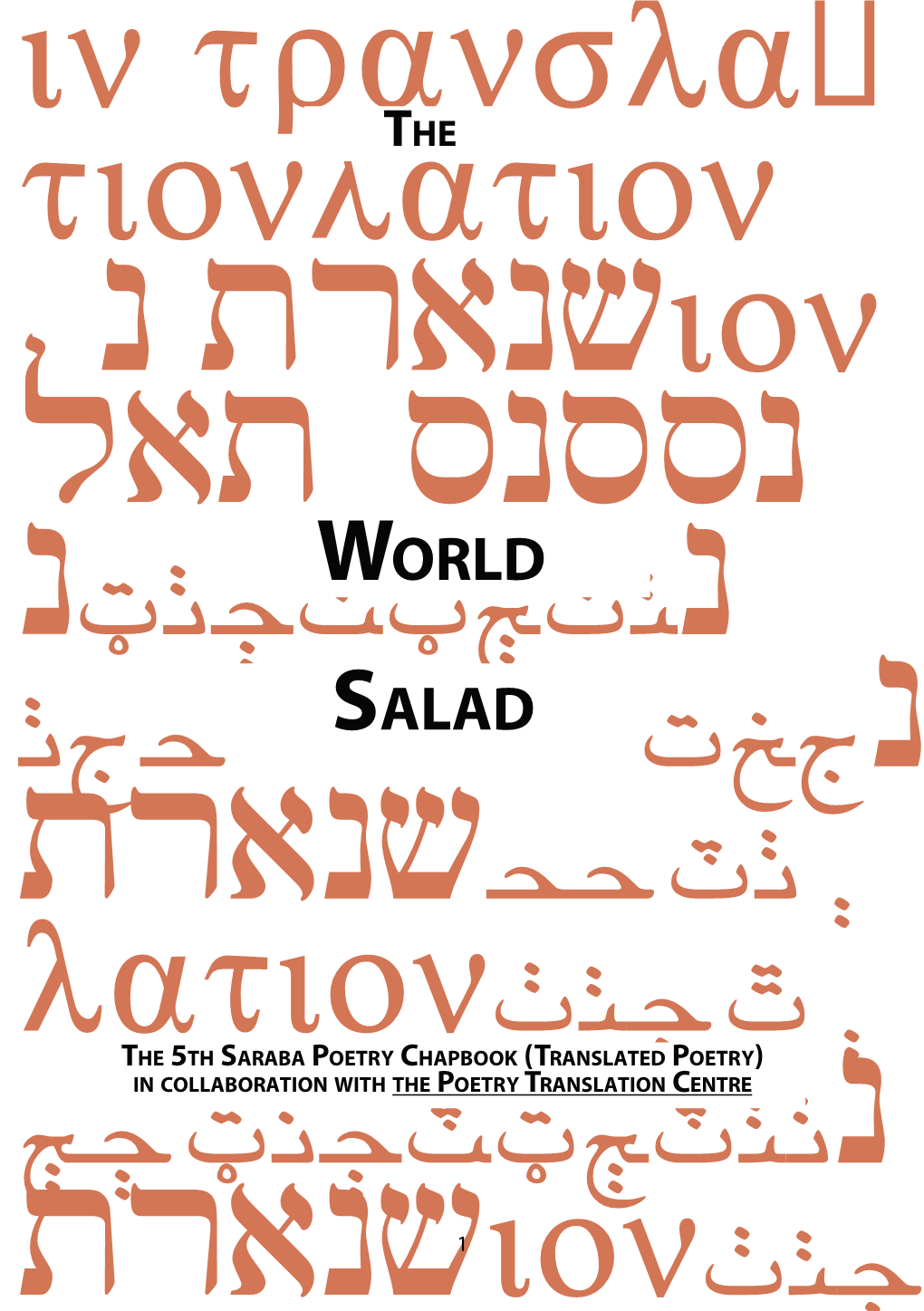

The Translated World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Virtuosic Touch: Hodeide, a Life with the Oud and More

A Virtuosic Touch: Hodeide, a Life with the Oud and More Ahmed I. Samatar He is as distinguished as any Somali of national accomplishment. Still tall with a straight back, the gait strong, the mind in full alert, the great- est living Somali master of the oud (kaman), Ahmed Ismail Hussein, Hodeide, is now nearly eighty. Like almost a million of his compatri- ots, he is in exile from the continuing violent misery that is the Somali Republic. It is December 27, 2007. We just ended a delicious and long lunch at one of London’s best Indian restaurants, a stone’s throw from the British Museum. He looks as formidable as the late André Segovia, the renowned Spanish and world-class guitarist who transformed that instrument into a treasure of classical music. If Hodeide was born to a country more integrated into the world, he could have been regarded as the Segovia of the oud—famous, rich, and more… We are sitting in my hotel room on a cool day in London, one of his many kaman instruments lovingly held on his lap and the famous and big right-hand fingers itching to strike and set us in at once a tantaliz- ingly sweet and sour mood. There is little doubt that Hodeide is a gifted man, a virtuoso that not only can manipulate the strings to exquisite sounds, but has proven to be capable of astonishing patriotic and romantic song compositions. Moreover, his knowledge of Somali musical performance is among the most arresting, with discriminating judgments to boot. -

In Somali Poetry

Oral Tradition, 20/2 (2005): 278-299 On the Concept of “Definitive Text” in Somali Poetry Martin Orwin Introduction: Concept of “Definitive Text” The concept of text is one central to the study of literature, both oral and written. During the course of the Literature and Peformance workshops organized by the AHRB (Arts and Humanities Research Board) Centre for Asian and African Literatures, the word “text” has been used widely and in relation to various traditions from around the world. Here I shall consider the concept of text and specifically what I refer to as “definitive text” in Somali poetry. I contend that the definitive text is central to the conception of maanso poetry in Somali and is manifest in a number of ways. I look at aspects of poetry that are recognized by Somalis and present these as evidence of “the quality of coherence or connectivity that characterizes text” (Hanks 1989:96). The concept of text understood here is, therefore, that of an “individuated product” (ibid.:97). Qualitative criteria both extra- and intratextual will be presented to support this conception. On the intratextual side, I, like Daniel Mario Abondolo, take “inspiration from the intrinsic but moribund, or dead and warmed-over, metaphor of text, i.e. ‘that which has been woven, weave’ (cf. texture) and see in texts a relatively high degree of internal interconnectedness via multiple non-random links” (2001:6). This inspiration is rooted in Western European language, but I find strong resonance in “Samadoon” by Cabdulqaadir Xaaji Cali1 (1995: ll. 147-52; trans. in Orwin 2001a:23): 1 In this paper I shall use the Somali spelling of names unless I am referring to an author who has published under an anglicized spelling of his or her name. -

Crafting Modern Somali Poetry: Lyric Features in Fad Galbeed by Gaarriye and Xabagbarsheed by Weedhsame

JOURNAL OF AFRICAN LANGUAGES AND LITERATURES 1/2020, 110-140 Crafting modern Somali poetry: Lyric features in Fad Galbeed by Gaarriye and Xabagbarsheed by Weedhsame MARTIN ORWIN School of Oriental and African Studies University of London [email protected] ABSTRACT This article presents two Somali poems in the jiifto metre: Fad Galbeed ‘Evening Cloud’ by Maxamed Xaashi Dhamac ‘Gaarriye’ and Xabagbarsheed ‘Royal Jelly’ by Xasan Daahir Ismaaciil ‘Weedhsame’. Each is recognized as a fine example of modern Somali poetry, and this article seeks to understand some of the reasons why this is so. The particular features considered are the use of address and apostrophe in Fad Galbeed and how this relates to the lyric present in each of the two parts of the poem. In Xabagbarsheed, on the other hand, I concentrate on sound-patterning looking at two sections in particular, one which displays assonance and another which displays interesting crafting of sound features which, it is suggested, foreground the sound of the alliterating consonant in a particularly appealing way. The discussion is centred on the poems themselves making detailed reference to the language used and how this contributes to the features and effects discussed. It is thus on the one hand a contribution to the study of the craft and aesthetics in Somali poetry. On the other hand, the manifestations of these aesthetic aspects coincide with what is presented in work on lyric. The article makes reference to this and, without going into detail on the theoretical aspects, seeks to begin to make a contribution from Somali poetry to this field of literary study. -

Professor Bogumił Witalis Andrzejewski 1922–1994

T PROFESSOR BOGUMIL WITALIS ANDRZEJEWSKI 1922-1994 B. W. Andrzejewski, known to all as ' Goosh', was born in Poznan in 1922. His family on his mother's side came from Eastern Poland and had been landowners until the nineteenth century but had lost their land, most probably during the Polish insurrections against the Russian tsars. His maternal grand- mother was widowed early in her marriage and made her living as a pianist. His mother died in 1939 after an illness and he owed much of his early upbringing to his grandmother. Goosh remembered her as a wonderful reciter of poetry and stories some of which he could still vividly recall years later. His father's family was from Western Poland, an area which had been part of the German Empire and in which the German language had been promoted to the detriment of the native Polish. This family background he felt had played a role in his strong sympathies with the Somali people who had also suffered under foreign domination. The Second World War broke out while he was in his penultimate year of high school and he was in Warsaw during the siege of the city, from which he escaped to join the Free Polish Forces abroad and to avoid forced labour. He undertook an arduous illegal journey, through Slovakia, Hungary, Yugoslavia, Greece and Turkey to Palestine, a journey lasting some five to six months full of hardship: hunger, sleeping outdoors in the freezing cold and arrest. He recounted one particular experience which illustrated the rigours he endured. With a friend, he had escaped from internment in Hungary and, during a snow storm, crossed Lake Balaton, one of Europe's largest lakes. -

Martin Orwin)

Impact case study (REF3b) Institution: SOAS Unit of Assessment: 27 Area Studies Title of case study: Enhancing Understanding of Somali Poetry and Culture (Martin Orwin) 1. Summary of the impact (indicative maximum 100 words) The primacy of oral poetry to Somali culture cannot be overstated: It is the primary form of cultural communication and the foremost vehicle through which Somali history, cultural values and contemporary concerns are expressed and transmitted. Through his pioneering analysis and sensitive translation into English of classical and contemporary Somali poems, Dr Martin Orwin has brought Somali poetry to the attention of Anglophone audiences, participating in web-accessible poetry projects and prominent events such as ‗Sonnet Sunday‘ and ‗Poetry Parnassus‘. Working with Somali poets and cultural organisations, Orwin‘s work has contributed to a more positive understanding of Somali culture and its place in world literature. 2. Underpinning research (indicative maximum 500 words) Dr Orwin studied Arabic, Amharic and Somali at SOAS where he has taught since 1992 and where he is currently Senior Lecturer in Somali and Amharic. He is currently the only full-time academic teaching Somali and Amharic languages and literatures in a UK university. His research on the subject of Somali poetry, of which a brief selection of underpinning publications is listed below, has sought above all to understand how Somali poetry is crafted as an aesthetic object. To this end, Dr Orwin researches the formal characteristics of varied styles of classical and contemporary Somali poetry, including its complex metrical patterns (each of which are most often exclusive to a particular style or thematic category of poetry), the recurring use of consonant sounds and alliteration. -

On the Musical Patterning of Sculpted Words: Exploring the Relationship Between Melody and Metre in a Somali Poetic Form

ON THE MUSICAL PATTERNING OF SCULPTED WORDS: EXPLORING THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN MELODY AND METRE IN A SOMALI POETIC FORM by FIACHA O' DUBHDA Introduction Somalia has often been called a "nation of bards", and poetry is frequently considered to be the most important form of artistic expression and social commentary in Somali society, a point made clear by Andrzejewski and Lewis when they state that "the Somali poetic heritage is a living force intimately connected with the vicissitudes of everyday life" (1964:3). It is evident from existing literature that Somali poetry is a powerful force fulfilling a multiplicity of social roles; it is intrinsic to the fabric of social action itself, from the negotiation of inter-clan relationships to the accompaniment of camel watering, from commenting on issues of public policy to those of technological development. What is not so evident is that all Somali poems can also be carriers of melody.1 These melodic qualities of Somali poetry are first noted fleetingly in the travel writings of Richard Burton: It is strange that a dialect which has no written character should so abound in poetry and eloquence. There are thousands of songs, some local, others general, upon all conceivable subjects, such as camel loading, drawing water...assisted by a tolerably regular alliteration and cadence, it can never be mistaken for prose, even without the song which invariably accompanies it. (Burton 1966:92) Ethnomusicology as a field has remained largely unaware of the fundamental importance of melodic constructs in Somali social and cultural life, and the musical aspects of Somali poetry have been rarely described in anything more than passing phrases like those of Burton's. -

41160714.Pdf

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Archivio Aperto di Ateneo Moolla, F.F. (2012). When orature becomes literature: Somali oral poetry and folktales in Somali novels. COMPARATIVE LITERATURE STUDIES, 49(3): 434-462 When Orature Becomes Literature: Somali Oral Poetry and Folk Tales in Somali Novels F. Fiona Moolla The University of the Western Cape, South Africa The concern of this essay is with the transformations which occur when what is variously termed, “orality”, the “oral tradition”, “oral literature” or “orature” is incorporated into literature in the context of Somali culture. While most sources use these terms interchangeably, Ngugi wa Thiongo, the Kenyan novelist, in a lecture titled “Oral Power and Europhone Glory”, stresses a subtle distinction of meaning between “orature” and “oral literature”. Ngugi notes that: “The term ‘orature’ was coined in the Sixties by Pio Zirimu, the late Ugandan linguist”.1 Ngugi observes that while Zirimu initially used the two terms interchangeably, he later identified “orature” as the more accurate term which indexed orality as a total system of performance linked to a very specific idea of space and time. The term “oral literature”, by contrast, incorporates and subordinates orality to the literary and masks the nature of orality as a complete system of its own. For this reason, “orature” is the preferred term in this essay. What this essay proposes is that the particular relationship of the spoken word and script in Somali culture points clearly to the need to reconsider and revise understandings of the oral- literate “dichotomy”. -

Language and National Identity in Africa

Language and National Identity in Africa edited by ANDREW SIMPSON 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX2 6DP Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York © 2008 editorial matter and organization Andrew Simpson © 2008 the chapters their various authors The moral rights of the authors have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published by Oxford University Press 2008 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book -

Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies a Literary Stylistic

Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies http://journals.cambridge.org/BSO Additional services for Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here A literary stylistic analysis of a poem by the Somali poet Axmed Ismaciil Diiriye ‘Qaasim’ Martin Orwin Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies / Volume 63 / Issue 02 / January 2000, pp 194 214 DOI: 10.1017/S0041977X00007187, Published online: 05 February 2009 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0041977X00007187 How to cite this article: Martin Orwin (2000). A literary stylistic analysis of a poem by the Somali poet Axmed Ismaciil Diiriye ‘Qaasim’. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, 63, pp 194214 doi:10.1017/S0041977X00007187 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/BSO, IP address: 212.219.138.14 on 11 Dec 2012 A literary stylistic analysis of a poem by the Somali poet Axmed Ismaciil Diiriye ' Qaasim?1 MARTIN ORWIN School of Oriental and African Studies 1. Introduction This article presents a stylistic analysis of a poem which we shall call Macaan iyo Qadhaadh, ' Sweet and bitter '2 by the Somali poet Axmed Ismaciil Diiriye ' Qaasim'. It will show ways in which the language has been crafted syntactic- ally, metrically, alliteratively and in other ways so as to contribute to the power and meaning of the poem as a whole. A stylistics-based approach has been followed looking at the actual language structures and stylistic devices used in the poem and ideas are proposed on their contribution to the meaning and power of the poem. -

War and Peace: an Anthology of Somali Literature

cover:cover 1/5/09 16:10 Page 1 War and Peace • Suugaanta Nabadda iyo Colaadda and Peace • Suugaanta Nabadda iyo War War and Peace Poetry is at the heart of Somali culture and has played a fundamental role War and Peace: in commenting on situations and influencing opinion in Somali society An anthology of Somali literature throughout its known history. Famous poets are listened to when they speak through their poems, and this influence continues today. War and Peace brings together for the first time a collection of poems on Suugaanta Nabadda issues of peace and conflict by some of the most famous poets of the first half of the twentieth century. At the time when these poems were composed all poetry was oral, and the poems in this book have been iyo Colaadda collected and written down by Axmed Aw Geeddi and Ismaaciil Aw Aadan. Stories which give an insight into the culture of peace and conflict in the past have also been collected and written down. The anthology is edited by Rashiid Sheekh Cabdillaahi ‘Gadhweyne’, a leading Somali scholar and intellectual, who also presents in his introduction a cultural and historical perspective on conflict and peace in Somali society through the lens of these poems in their social and historical context. War and Peace is not just an important record of classical Somali literature: it provides a fascinating insight into the role of poetry in Somali culture, the reasons for conflict in Somali society, and the ways in which conflicts were resolved and peace restored. Suugaanta Nabadda iyo Colaadda Waa suugaan iyo sheekooyin ka mid ah soojireenka hadalka afka uun lagu tabiyo (oral traditions) oo markii u horreysay lagu joojiyey dhigaal si habsami ah looga tixraaci karo. -

Bodari's Breakthrough and the Construction of the Modern Somali

Elmi Bodari and the Construction of the Modern Somali Subject in a Colonial and Sufi Context Jamal Abdi Gabobe A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2014 Reading Committee: Terri L. Deyoung, Chair Albert J. Sbragia Frederick Michael Lorenz Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Comparative Literature ©Copyright 2014 Jamal Abdi Gabobe University of Washington Abstract Elmi Bodari and the Construction of the Modern Somali Subject in a Colonial and Sufi Context Jamal Abdi Gabobe Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Doctor Terri Deyoung Near Eastern Languages and Civilization Elmi Bodari was the first Somali poet to compose poems exclusively about the theme of love. Many Somalis believe that it was his unrequited love that caused his early death. His personal tragedy and poems have earned him a unique place in Somali literature. Most accounts of Elmi Bodari’s poetry dwell on this aspect of his life and poetry. This study argues that his innovations were more far-reaching and that his poetry was instrumental for the rise of the modern Somali subject. An essential part of the modernism in Somali poetry that was launched by Elmi Bodari was the supplanting of the ideal of the traditional warrior hero by that of the lover as a hero. The study traces the trajectory and contours of this change in Somali poetry. It also scrutinizes the colonial and Sufi context in which Elmi Bodari lived and composed his poems and his creative response to it. Central to the new outlook pioneered by Elmi Bodari in Somali oral verse was inwardness and constant self-examination. -

In Somali Poetry

Oral Tradition, 20/2 (2005): 278-299 On the Concept of “Definitive Text” in Somali Poetry Martin Orwin Introduction: Concept of “Definitive Text” The concept of text is one central to the study of literature, both oral and written. During the course of the Literature and Peformance workshops organized by the AHRB (Arts and Humanities Research Board) Centre for Asian and African Literatures, the word “text” has been used widely and in relation to various traditions from around the world. Here I shall consider the concept of text and specifically what I refer to as “definitive text” in Somali poetry. I contend that the definitive text is central to the conception of maanso poetry in Somali and is manifest in a number of ways. I look at aspects of poetry that are recognized by Somalis and present these as evidence of “the quality of coherence or connectivity that characterizes text” (Hanks 1989:96). The concept of text understood here is, therefore, that of an “individuated product” (ibid.:97). Qualitative criteria both extra- and intratextual will be presented to support this conception. On the intratextual side, I, like Daniel Mario Abondolo, take “inspiration from the intrinsic but moribund, or dead and warmed-over, metaphor of text, i.e. ‘that which has been woven, weave’ (cf. texture) and see in texts a relatively high degree of internal interconnectedness via multiple non-random links” (2001:6). This inspiration is rooted in Western European language, but I find strong resonance in “Samadoon” by Cabdulqaadir Xaaji Cali1 (1995: ll. 147-52; trans. in Orwin 2001a:23): 1 In this paper I shall use the Somali spelling of names unless I am referring to an author who has published under an anglicized spelling of his or her name.