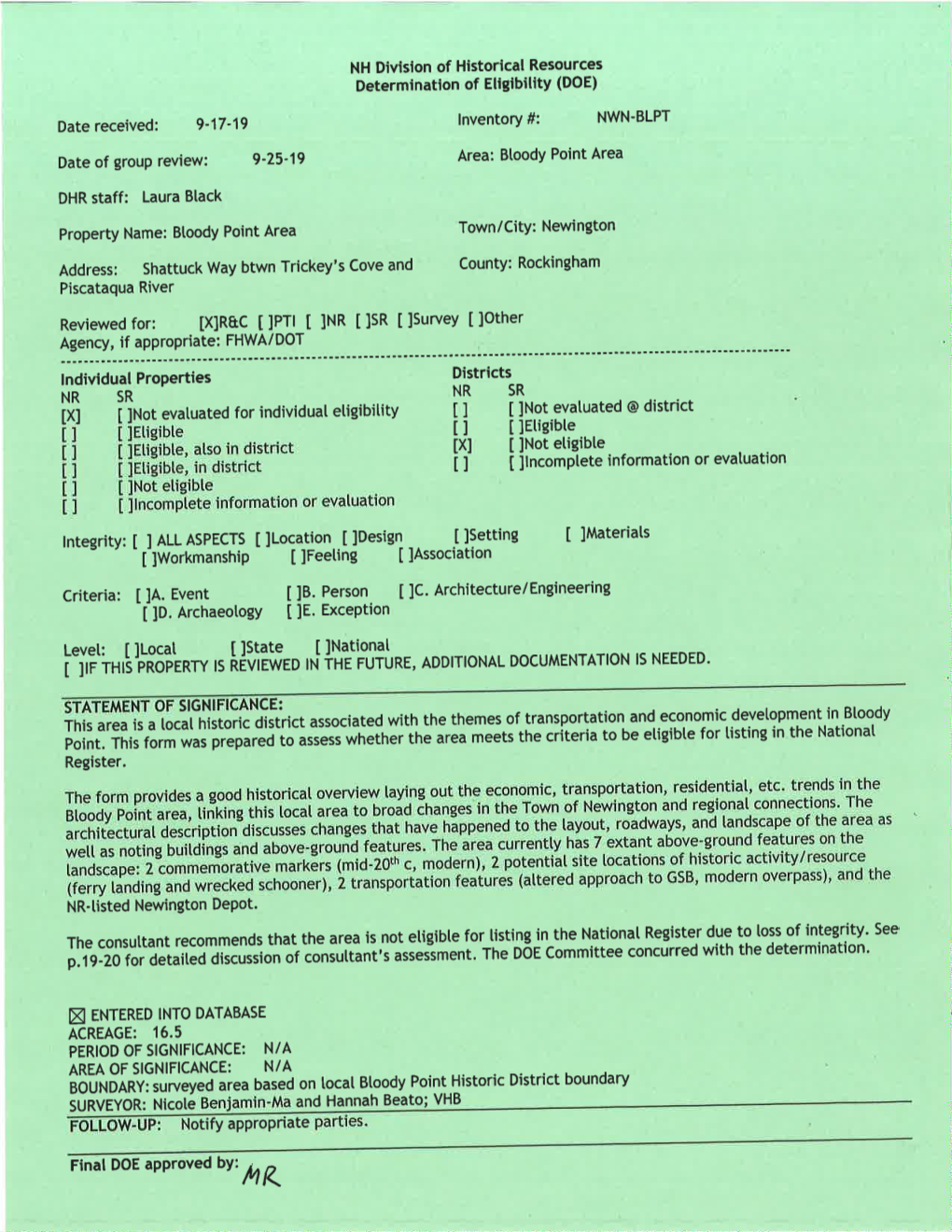

New Hampshire Division of Historical Resources Page 1 of 26 Mapping Information Updated 6/2015 AREA FORM AREA NAME: BLOODY POINT

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

16817.00 NHDOT PIN: PK 13678E Prepared by (Name/F

Project Name: ME-NH Connections Study FHWA No: PR-1681(700X) MaineDOT PIN: 16817.00 NHDOT PIN: PK 13678E Prepared by (Name/Firm): Lauren Meek, P.E., HNTB Contract Number: 20090325000000005165 Technical Memorandum No.: 3 - Navigational Needs of the Piscataqua River Date (month/year): August, 2009 Subject: Navigational Data for the Sarah Mildred Long and Portsmouth Memorial Bridges Background This Tech Memo is a supplement to a 2006 HNTB memo that identified issues and preferences for users of the Piscataqua River during the rehabilitation of the Portsmouth Memorial Bridge based on a mail-back navigational survey. This 2006 memo is attached as Appendix A. Purpose The purpose of this memorandum is to: a.) summarize the existing horizontal and vertical clearances and identify the minimum required bridge lifts versus the actual number of bridge lifts of the Sarah Mildred Long and Portsmouth Memorial Bridges; b.) identify the users of the river; c.) analyze the bridge lift records; d.) summarize feedback from users of the river and those responsible for the river’s operation. Additionally, a survey to address the current and future uses has been sent to users of the river. A separate technical memorandum will be prepared with the analysis of the responses when received. 1 Methodology a. Existing Clearances and Frequency of Lifts Table 1 provides the clearances for the three lower Piscataqua River bridges as identified on the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Chart 13283, 20th Edition. The vertical clearance is the distance between mean high water and the underside of the bridge. The Portsmouth Memorial and Sarah Mildred Long Bridges have lift spans that provide additional vertical clearance when opened. -

Strafford Mpo Years Metropolitan 2021- Transportation Plan 2045

STRAFFORD MPO YEARS METROPOLITAN 2021- TRANSPORTATION PLAN 2045 APPROVED: June 18, 2021 Preparation of this report has been financed through funds received from the U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Transit Administration, Federal Highway Administration, and by the dues-paying members of the Strafford Regional Planning Commission. The Role of the Metropolitan Planning Organization Municipalities Strafford Metropolitan Planning Organization (SMPO) is a subdivision Barrington New Durham of Strafford Regional Planning Commission and carries out all Brookfield Newmarket transportation planning efforts. Dover Northwood Strafford MPO staff work closely with the NH Department of Durham Nottingham Transportation to implement data collection programs, assist and Farmington Rochester advocate for local transit agencies and municipal projects, and create Lee Rollinsford long-range plans which address safety and quality of life. Madbury Somersworth Officers Middleton Strafford Milton Wakefield David Landry, Chair Peter Nelson, Vice Chair Staff Tom Crosby, Secretary/Treasurer Jen Czysz Kyle Pimental Contact Us! Shayna Sylvia 150 Wakefield Street, Suite 12, Rochester, NH 03687 Colin Lentz Tel: (603) 994-3500 Rachel Dewey E-mail: [email protected] James Burdin Nancy O’Connor Website: www.strafford.org Stephen Geis Facebook: @StraffordRegionalPlanningCommission Jackson Rand Twitter: @StraffordRPC Alaina Rogers Instagram: @strafford.rpc Natalie Moles Megan Taylor-Fetter TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .................................................1 -

Community Guide

ROCHESTERNH.ORG GREATER ROCHESTER CHAMBER OF COMMERCE 2016 • 1 It’s about People. 7HFKQRORJ\ 7UXVW frisbiehospital.com People are the foundation of what health that promotes faster healing, better health, care is about. People like you who are and higher quality of life. looking for the best care possible—and It’s this approach that has allowed us to people like the professionals at Frisbie develop trust with our patients, and to Memorial Hospital who are dedicated to become top-rated nationally for our quality providing it. of care and services. :HXVHWKHODWHVWWHFKQRORJ\WRKHOSÀQG VROXWLRQVWKDWEHQHÀWSDWLHQWV7HFKQRORJ\ 11 Whitehall Road, Rochester, NH 03867 | Phone (603) 332-5211 2 • 2016 GREATER ROCHESTER CHAMBER OF COMMERCE ROCHESTERNH.ORG contents Editor: 4 A Message from the Chamber Greater Rochester Chamber of Commerce 5 City of Rochester Welcome 6 New Hampshire Economic Development Photography Compliments of: 7 New Hampshire & Rochester Facts Cornerstone VNA Frisbie Memorial Hospital 8 Rochester – Ideal Destination, Convenient Location Great Bay Community College 10 Rochester History Greater Rochester Chamber of Commerce Revolution Taproom & Grill 11 Arts, Culture & Entertainment Rochester Economic Development 13 Rochester Business & Industry Rochester Fire Department A Growing & Diverse Economy Rochester Historical Society Rochester Main Street 14 Rochester Growth & Development Rochester Opera House Business & Industrial Parks Rochester Police Department 15 Rochester Commercial Districts Produced by: 16 Helpful Information Rochester -

Designation of Critical Habitat for the Gulf of Maine, New York Bight, And

Federal Register / Vol. 81, No. 107 / Friday, June 3, 2016 / Proposed Rules 35701 the Act, including the factors identified Recovery and State Grants, Ecological Public hearings and public in this finding and explanation (see Services Program, U.S. Fish and information meetings: We will hold two Request for Information, above). Wildlife Service. public hearings and two public informational meetings on this proposed Conclusion Authority rule. We will hold a public On the basis of our evaluation of the The authority for these actions is the informational meeting from 2 to 4 p.m., information presented under section Endangered Species Act of 1973, as in Annapolis, Maryland on Wednesday, 4(b)(3)(A) of the Act, we have amended (16 U.S.C. 1531 et seq.). July 13 (see ADDRESSES). A second determined that the petition to remove Dated: May 25, 2016. public informational meeting will be the golden-cheeked warbler from the Stephen Guertin, held from 3 to 5 p.m., in Portland, List of Endangered and Threatened Maine on Monday, July 18 (see Wildlife does not present substantial Acting Director, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. ADDRESSES). We will hold two public scientific or commercial information [FR Doc. 2016–13120 Filed 6–2–16; 8:45 am] hearings, from 3 to 5 p.m. and 6 to 8 indicating that the requested action may p.m., in Gloucester, Massachusetts on BILLING CODE 4333–15–P be warranted. Therefore, we are not Thursday, July 21 (see ADDRESSES). initiating a status review for this ADDRESSES: You may submit comments, species. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE identified by the NOAA–NMFS–2015– We have further determined that the 0107, by either of the following petition to list the U.S. -

Official List of Public Waters

Official List of Public Waters New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services Water Division Dam Bureau 29 Hazen Drive PO Box 95 Concord, NH 03302-0095 (603) 271-3406 https://www.des.nh.gov NH Official List of Public Waters Revision Date October 9, 2020 Robert R. Scott, Commissioner Thomas E. O’Donovan, Division Director OFFICIAL LIST OF PUBLIC WATERS Published Pursuant to RSA 271:20 II (effective June 26, 1990) IMPORTANT NOTE: Do not use this list for determining water bodies that are subject to the Comprehensive Shoreland Protection Act (CSPA). The CSPA list is available on the NHDES website. Public waters in New Hampshire are prescribed by common law as great ponds (natural waterbodies of 10 acres or more in size), public rivers and streams, and tidal waters. These common law public waters are held by the State in trust for the people of New Hampshire. The State holds the land underlying great ponds and tidal waters (including tidal rivers) in trust for the people of New Hampshire. Generally, but with some exceptions, private property owners hold title to the land underlying freshwater rivers and streams, and the State has an easement over this land for public purposes. Several New Hampshire statutes further define public waters as including artificial impoundments 10 acres or more in size, solely for the purpose of applying specific statutes. Most artificial impoundments were created by the construction of a dam, but some were created by actions such as dredging or as a result of urbanization (usually due to the effect of road crossings obstructing flow and increased runoff from the surrounding area). -

New Hampshire River Protection and Energy Development Project Final

..... ~ • ••. "'-" .... - , ... =-· : ·: .• .,,./.. ,.• •.... · .. ~=·: ·~ ·:·r:. · · :_ J · :- .. · .... - • N:·E·. ·w··. .· H: ·AM·.-·. "p• . ·s;. ~:H·1· ··RE.;·.· . ·,;<::)::_) •, ·~•.'.'."'~._;...... · ..., ' ...· . , ·....... ' · .. , -. ' .., .- .. ·.~ ···•: ':.,.." ·~,.· 1:·:,//:,:: ,::, ·: :;,:. .:. /~-':. ·,_. •-': }·; >: .. :. ' ::,· ;(:·:· '5: ,:: ·>"·.:'. :- .·.. :.. ·.·.···.•. '.1.. ·.•·.·. ·.··.:.:._.._ ·..:· _, .... · -RIVER~-PR.OT-E,CT.10-N--AND . ·,,:·_.. ·•.,·• -~-.-.. :. ·. .. :: :·: .. _.. .· ·<··~-,: :-:··•:;·: ::··· ._ _;· , . ·ENER(3Y~EVELOP~.ENT.PROJ~~T. 1 .. .. .. .. i 1·· . ·. _:_. ~- FINAL REPORT··. .. : .. \j . :.> ·;' .'·' ··.·.· ·/··,. /-. '.'_\:: ..:· ..:"i•;. ·.. :-·: :···0:. ·;, - ·:··•,. ·/\·· :" ::;:·.-:'. J .. ;, . · · .. · · . ·: . Prepared by ~ . · . .-~- '·· )/i<·.(:'. '.·}, •.. --··.<. :{ .--. :o_:··.:"' .\.• .-:;: ,· :;:· ·_.:; ·< ·.<. (i'·. ;.: \ i:) ·::' .::··::i.:•.>\ I ··· ·. ··: · ..:_ · · New England ·Rtvers Center · ·. ··· r "., .f.·. ~ ..... .. ' . ~ "' .. ,:·1· ,; : ._.i ..... ... ; . .. ~- .. ·· .. -,• ~- • . .. r·· . , . : . L L 'I L t. ': ... r ........ ·.· . ---- - ,, ·· ·.·NE New England Rivers Center · !RC 3Jo,Shet ·Boston.Massachusetts 02108 - 117. 742-4134 NEW HAMPSHIRE RIVER PRO'l'ECTION J\ND ENERGY !)EVELOPMENT PBOJECT . -· . .. .. .. .. ., ,· . ' ··- .. ... : . •• ••• \ ·* ... ' ,· FINAL. REPORT February 22, 1983 New·England.Rivers Center Staff: 'l'bomas B. Arnold Drew o·. Parkin f . ..... - - . • I -1- . TABLE OF CONTENTS. ADVISORY COMMITTEE MEMBERS . ~ . • • . .. • .ii EXECUTIVE -

Phase II Highway Corridor Strategy Descriptions Technical

ENTRAL ORK OUNTY ONNECTIONS TUDY CENTRAL YORK COUNTY CONNECTIONS STUDY PHASE II HIGHWAY CORRIDOR STRATEGY DESCRIPTIONS PHASE II TECHNICAL MEMORANDUM SEPTEMBER 2011 Prepared for: Maine Department Maine Turnpike Authority of Transportation Prepared by: In association with: Morris Communications • Kevin Hooper Associates T.Y. Lin • Planning Decisions • Facet Decision Systems Dr. Charles Colgan, University of Southern Maine • Evan Richert Normandeau Associates • Preservation Company This document is formatted for two-sided printing. Document II-4 ENTRAL ORK OUNTY ONNECTIONS TUDY CENTRAL YORK COUNTY CONNECTIONS STUDY 1 INTRODUCTION This document summarizes the potential highway corridor improvements – called strategies – that are being tested and evaluated for Phase II of the Central York County Connections Study (CYCCS). Phase II Highway Strategies are a starting point in the development and consideration of candidate improvements for the study; they are not recommendations, nor are they the only strategies that will be studied. Phase II strategies are conceptual in nature, and not yet detailed, specific proposals. Strategies considered later in the study during Phase III, as well as those ultimately recommended by the study, may differ considerably from the initial strategies currently under evaluation in Phase II. Specific aspects of these initially proposed strategies may be dropped, carried forward or combined in different ways, depending on the results of the analyses conducted during Phase II. The study is guided by a Purpose and Need Statement, which articulates that the study is to identify transportation and related land use strategies that enhance economic development opportunities and preserve and improve the regional transportation system. Additional information on the study, including the full Purpose and Need Statement, is available at the project website: www.connectingyorkcounty.org. -

1982 Maine River's Study Appendix H - Rivers with Historical Landmarks & Register Sites

1982 Maine River's Study Appendix H - Rivers with Historical Landmarks & Register Sites HISTORI RIVER NAME HISTORIC SITE/PLACE C COUNTY LOCATION LINK Androscoggin River Pejepscot Paper Mill RHP Sagadahoc Topsham https://www.mainememory.net/sitebuilder/site/201/page/460/display Androscoggin River Barker Mill RHP Androscoggin Auburn https://tinyurl.com/y8wsy2a6 Bagaduce River Fort George RHP Hancock Castine https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fort_George_(Castine,_Maine) Carrabasset River (Lemon Stream) New Portland Wire Bridge RHP Somerset New Portland http://www.maine.gov/mdot/historicbridges/otherbridges/wirebridge/index.shtml Damariscotta Oyster Shell Heaps (Whaleback) Damariscotta River RHP Lincoln Damariscotta http://tinyurl.com/m9vgk84 Kennebec Franklin Dead River Dead River Arnold Trail to Quebec RHP Somerset Chain of Ponds http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Benedict_Arnold%27s_expedition_to_Quebec Ellis River Lovejoy Bridge RHP Oxford South Andover http://www.maine.gov/mdot/historicbridges/coveredbridges/lovejoybridge/ Kenduskeag Stream Robyville Bridge RHP Penobscot Bangor http://www.maine.gov/mdot/historicbridges/coveredbridges/robyvillebridge/ Kenduskeag Stream Morse Bridge RHP Penobscot Bangor http://bangorinfo.com/Focus/focus_kenduskeag_stream.html Kennebec River Fort Baldwin RHP Sagadahoc Popham Beach http://www.maine.gov/cgi-bin/online/doc/parksearch/details.pl?park_id=86 Kennebec River Fort Popham RHP Sagadahoc Popham Beach http://www.fortwiki.com/Fort_Popham Percy and Small Shipyard Kennebec River Maritime Museum District* RHP Sagadahoc -

Toll Roads in the United States: History and Current Policy

TOLL FACILITIES IN THE UNITED STATES Bridges - Roads - Tunnels - Ferries August 2009 Publication No: FHWA-PL-09-00021 Internet: http://www.fhwa.dot.gov/ohim/tollpage.htm Toll Roads in the United States: History and Current Policy History The early settlers who came to America found a land of dense wilderness, interlaced with creeks, rivers, and streams. Within this wilderness was an extensive network of trails, many of which were created by the migration of the buffalo and used by the Native American Indians as hunting and trading routes. These primitive trails were at first crooked and narrow. Over time, the trails were widened, straightened and improved by settlers for use by horse and wagons. These became some of the first roads in the new land. After the American Revolution, the National Government began to realize the importance of westward expansion and trade in the development of the new Nation. As a result, an era of road building began. This period was marked by the development of turnpike companies, our earliest toll roads in the United States. In 1792, the first turnpike was chartered and became known as the Philadelphia and Lancaster Turnpike in Pennsylvania. It was the first road in America covered with a layer of crushed stone. The boom in turnpike construction began, resulting in the incorporation of more than 50 turnpike companies in Connecticut, 67 in New York, and others in Massachusetts and around the country. A notable turnpike, the Boston-Newburyport Turnpike, was 32 miles long and cost approximately $12,500 per mile to construct. As the Nation grew, so did the need for improved roads. -

A Technical Characterization of Estuarine and Coastal New Hampshire New Hampshire Estuaries Project

AR-293 University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository PREP Publications Piscataqua Region Estuaries Partnership 2000 A Technical Characterization of Estuarine and Coastal New Hampshire New Hampshire Estuaries Project Stephen H. Jones University of New Hampshire Follow this and additional works at: http://scholars.unh.edu/prep Part of the Marine Biology Commons Recommended Citation New Hampshire Estuaries Project and Jones, Stephen H., "A Technical Characterization of Estuarine and Coastal New Hampshire" (2000). PREP Publications. Paper 294. http://scholars.unh.edu/prep/294 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Piscataqua Region Estuaries Partnership at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in PREP Publications by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Technical Characterization of Estuarine and Coastal New Hampshire Published by the New Hampshire Estuaries Project Edited by Dr. Stephen H. Jones Jackson estuarine Laboratory, university of New Hampshire Durham, NH 2000 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................i LIST OF TABLES ....................................................................................................vi LIST OF FIGURES.................................................................................................viii -

New Hampshire

DOVER NEW HAMPSHIRE City of Opportunity A Message from Dover Economic reetings, Development and City Planning G & Community Development On behalf of the city of Dover, NH, I thank you for considering our great community. Dover was established in 1623 and has a rich history of industry, education and Dover, New Hampshire: Unique, Cooperative, culture which rivals any community in the State or region. Proactive. That’s how we see our city. Dover has worked hard to build a business-friendly, proactive government Dover is a great place to live, work and play. From our his- infrastructure, where departments cooperate to assist toric downtown to our rich cultural events, Dover is a place existing businesses, and relocating companies, so that where people want to settle down and raise their families. both fulfill their potential. Great schools, family friendly events and close proximity One example of this cooperation, is the close to the State University hub add to the appeal of Dover. working relationship between the Dover Business & Industrial Development Authority and the City of Dover Our proximity to major highways, deep water ports, and Planning and Community Development Department. regional airports adds to the draw of an already vibrant Both entities work together with our clients from start to community. Dover is within a one hour drive of major finish. This integration ensures that permitting, engineer- cities, the Atlantic Ocean, the White Mountains and a ing, plan acceptance, variance consideration, and zoning number of prime hiking and ski resorts. approvals happen in a transparent and expeditious man- ner. There is a keen awareness that common sense and Dover offers an educated workforce, a technologically flexibility within the rules are needed to make projects advanced infrastructure and a proactive Planning Board work. -

Thruway Authority Toll Adjustment Proposal December 19, 2019

12/19/2019 Thruway Authority Toll Adjustment Proposal December 19, 2019 Thruway’s Current State 570 miles or 2,840 lanes miles 266.4 million transactions = $736.5 million in toll revenues E-ZPass customers 77% system-wide GMMCB E-ZPass customers 86.7% Overall 16% - Out-of-state accounts 20.5% - E-ZPass commuters 1 12/19/2019 Fiscal Discipline Tolls have not increased since 2010 How ? Balanced budgets Avg. 1.2% annual growth since 2010 Thruway Stabilization Fund = $2 billion Commitment to Safety & Reliability Decade of reinvestment in the system Replaced/rehabilitated 116 bridges Resurfaced 2,000 lanes miles of highway Advanced $6.6 billion capital program Replaced/added $141 million in vehicles and equipment 2 12/19/2019 Thruway of the Future Cashless Tolling Gov. Mario M. Cuomo Bridge System-wide in 2020 (GMMCB) Cashless Tolling Benefits Safer travel Reduced congestion Lowered emissions 3 12/19/2019 The Time is Now… Both spans of GMMCB open to traffic System-wide cashless tolling conversion by the end of 2020 Additional revenues will: Allow the Thruway Authority to responsibly meet capital needs Support outstanding debt Continue to provide reliable service to its patrons What They Said 4 12/19/2019 Proposal Components GMMCB Commuter Discount Plan (40% Discount) New Westchester and Rockland Resident Discount Plan for the GMMCB – Tolls remain flat through 2022 NY E-ZPass Customers Continue to Save Money (Base Rate) Non-NY E-ZPass Rate (15% above the NY E-ZPass Rate) Tolls By Mail Rate (30% > NY E-ZPass) $2 Surcharge on the Tolls by Mail Bill Commercial rates remain below nearby crossings Proposed Toll Schedule Gov.