Materiality in Bruno Munari's Book Objects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Italian Futurism, 1909–1944: Reconstructing the Universe Published on Iitaly.Org (

Italian Futurism, 1909–1944: Reconstructing the Universe Published on iItaly.org (http://www.iitaly.org) Italian Futurism, 1909–1944: Reconstructing the Universe Natasha Lardera (February 21, 2014) On view at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, until September 1st, 2014, this thorough exploration of the Futurist movement, a major modernist expression that in many ways remains little known among American audiences, promises to show audiences a little known branch of Italian art. Giovanni Acquaviva, Guillaume Apollinaire, Fedele Azari, Francesco Balilla Pratella, Giacomo Balla, Barbara (Olga Biglieri), Benedetta (Benedetta Cappa Marinetti), Mario Bellusi, Ottavio Berard, Romeo Bevilacqua, Piero Boccardi, Umberto Boccioni, Enrico Bona, Aroldo Bonzagni, Anton Giulio Bragaglia, Arturo Bragaglia, Alessandro Bruschetti, Paolo Buzzi, Mauro Camuzzi, Francesco Cangiullo, Pasqualino Cangiullo, Mario Carli, Carlo Carra, Mario Castagneri, Giannina Censi, Cesare Cerati, Mario Chiattone, Gilbert Clavel, Bruno Corra (Bruno Ginanni Corradini), Tullio Crali, Tullio d’Albisola (Tullio Mazzotti), Ferruccio Demanins, Fortunato Depero, Nicolaj Diulgheroff, Gerardo Dottori, Fillia (Luigi Page 1 of 3 Italian Futurism, 1909–1944: Reconstructing the Universe Published on iItaly.org (http://www.iitaly.org) Colombo), Luciano Folgore (Omero Vecchi), Corrado Govoni, Virgilio Marchi, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, Alberto Martini, Pino Masnata, Filippo Masoero, Angiolo Mazzoni, Torido Mazzotti, Alberto Montacchini, Nelson Morpurgo, Bruno Munari, N. Nicciani, Vinicio Paladini -

Curriculum Vitae 1

Golan/Curriculum Vitae 1 Romy Golan Ph.D Program in Art History The Graduate Center, City University of New York 365 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10016-4309 email: [email protected] CURRICULUM VITAE Education: Ph. D. Courtauld Institute of Art, University of London, England, 1989 Dissertation: "A Moralized Landscape: The Organic Image of France Between the Two World Wars" M.A. Courtauld Institute of Art, University of London, 1982 (Thesis: "Roberto E. Matta, 1937-1947: The Last Phase of Surrealism") M.A course, History Department, Tel Aviv University, Israel, 1981 (Thesis: "Ideological Paradoxes in Nazi Architecture") B.A. Courtauld Institute of Art, University of London, 1980 Enrolled in Bezalel School of Fine Arts, Jerusalem, Israel, 1976-77 French Baccalaureat. Lycée Français Chateaubriand, Rome, Italy (with honors), 1976 Awards and Fellowships: -I Tatti, Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance, Florence (Fall 2018) -Italian Academy of Columbia University Fellowship (2014) -Sterling and Francis Clark Art Institute Fellowship (2013) -Samuel and Ronnie Heyman Prize for outstanding scholarly publication by Junior Faculty Members of the Humanities at Yale for Modernity and Nostalgia: Art and Politics in France between the Wars (1995) -Frederick W. Hilles publication grant (1994) -A. Whitney Griswold Faculty Research grant (1993) -Henry Allen Moe Prize for Catalogues of Distinction in the Arts for co-authorship of The Circle of Montparnasse: Jewish Artists in Paris 1905-1945 (1985) -Distinction for M.A thesis, Courtauld Institute -

ED 092 871 TITLE INSTITUTION PUB DATE AVAILABLE from DOCUMENT RESUME CS 001 095 Bibliography. Books for Children. 1974 Edition

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 092 871 CS 001 095 TITLE Bibliography. Books for Children. 1974 Edition. INSTITUTION Association for Childhood Education International, Washington, D.C. PUB DATE 74 NOTE 112p. AVAILABLE FROM Association for Childhood Education International, 3615 Wisconsin Avenue, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20016 ($2.75, Orders under $5.00 must be prepaid by check payable to ACEI) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.75 HC Not Available from EDRS. PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS *Adolescent Literature; *Annotated Bibliographies; *Childrens Books; Childrens Literature; Folklore Books; Reading; *Reading Materials; *Reading Material Selection ABSTRACT The books selected for this bibliography were measured against commonly accepted literary standards. Fiction was considered in terms of important themes: substantial plots, effective style, valid management of time and place settings, and believable . characters whose personalities hold significance for children from preschoolers to 14-year-olds. Nonfiction was selected for its accuracy, its style, and the pertinency of its subject matter to the age level addressed, to objectively identified reading interests of children, and to curriculum relationships. The contents include: "Introduction"; "Awards and Their Symbols"; "Using the Bibliography"; "Picture and picture Story Books," which looks at ABC books, books with no or few words, fiction and folklore, and nonfiction; "Reading in Its Early Stages," which presents fiction and folklore and nonfiction; "For Middle and Older Children," which lists fiction, folklore, and nonfiction books; "Poetry and Verse," which lists anthologies and single writers; "Religion"; and "Story and Miscellany Collections," which is divided into the categories of general, seasons and holidays, reference books, directory of publishers, index of titles, and index of authors. -

SPERONE WESTWATER 257 Bowery New York 10002 T + 1 212 999 7337 F + 1 212 999 7338

SPERONE WESTWATER 257 Bowery New York 10002 T + 1 212 999 7337 F + 1 212 999 7338 www.speronewestwater.com Painting in Italy 1910s-1950s: Futurism, Abstraction, Concrete Art 30 October – 22 December 2015 New York, 29 September 2015—Sperone Westwater is pleased to present Painting in Italy 1910s- 1950s: Futurism, Abstraction, Concrete Art, a group exhibition of influential Italian painters working before, during and after World War II, curated by Gian Enzo Sperone. Featuring over 120 paintings spanning three major artistic movements, the exhibition illustrates the diversity and singularity of abstract art in Italy, seeking to afford more focused attention to a group of artists who revolutionized the historical sweep of painting in the context of interwar and postwar Europe and the United States. This exhibition concerns three periods from the early 1910s through the late 1950s, beginning with Giacomo Balla and Enrico Prampolini’s embrace of the Futurist manifesto and charting the development of Italian abstract painting under the growing political pressures of Fascism. The works on view are united in their vigorous challenge of the traditions of their time, each propelled by spirited experimentation and fervent revolutionary impulse. Often transcending the typical Futurist subject matter of racing car and mechanical city-scape, these works mark a distinct movement away from figuration as the primary vessel for an expression of feeling, instead investigating the emotional value of line, shape and color. As abstractionist painter Theo Van -

Modern & Contemporary

Modern & Contemporary Art New Bond Street, London | 27 June 2019 Detail lot 13 Detail lot 39 Detail lot 23 Detail lot 36 Modern & Contemporary Art New Bond Street, London I Thursday 27 June 2019 at 4pm VIEWING ENQUIRIES CUSTOMER SERVICES REGISTRATION 101 New Bond Street, London Cassi Young Monday to Friday 8.30am to 6pm IMPORTANT NOTICE Saturday 22 June 11am - 5pm +44 (0) 20 7468 5815 +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 Please note that all customers, Sunday 23 June 11am - 5pm [email protected] irrespective of any previous activity Monday 24 June 9am - 4pm As a courtesy to intending with Bonhams, are required to Tuesday 25 June 9.30am - 5pm Itziar Ramos bidders, Bonhams will provide a complete the Bidder Registration Wednesday 26 June 9am - 5pm +44 (0) 20 7468 8263 written indication of the physical Form in advance of the sale. The Thursday 27 June 9am - 1pm [email protected] condition of lots in this sale if a form can be found at the back of request is received up to 24 hours every catalogue and on our website SALE NUMBER THANKS TO: before the auction starts. This at www.bonhams.com and should written Indication is issued subject be returned by email or post to the 25601 Benedetta Alpini Olivier Morris-Jones to Clause 3 of the Notice to Bidders. specialist department or to the bids department at [email protected] CATALOGUE William Mees Tim Readhead ILLUSTRATIONS £30.00 Nathan Brown Front cover: Lot 33 To bid live online and / or leave Back cover: Lot 27 internet bids please go to BIDS © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, www.bonhams.com/auctions/25601 +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 London 2019 and click on the Register to bid link +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 fax at the top left of the page. -

Avant-Garde and Contemporary Art Books & Ephemera

Avant-garde and Contemporary Art Books & Ephemera Sanctuary Books [email protected] (212) 861-1055 2 [Roh, Franz and Jan Tschichold] foto-auge / oeil et photo / photo-eye. Akademischer Verlag Dr. Fritz Wedekind & Co., Stuttgart, 1929. Paperback. 8.25 x 11.5”. Condition: Good. First Edition. 76 photos of the period by Franz Roh and Jan Tschichold, with German, French and English text, 18pp. of introductory text and 76 photographs and photographic experiments (one per page with captions for each) with a final page of photographers addresses at the back. Franz Roh introduction: “Mechanism and Expression: The Essence and Value of Photography”. Cover and interior pages designed by Jan Tschichold, Munich featuring El Lissitzky’s 1924 self-portrait, “The Constructor” on the cover. One of the most important and influential publications about modern photography and the New Vision published to accompany Stuttgart’s 1929 Film und Foto exhibition with examples by but not limited to: Eugene Atget, Andreas Feininger, Florence Henri, Lissitzky, Max Burchartz, Max Ernst, George Grosz and John Heartfield, Hans Finsler, Tschichold, Vordemberge Gildewart, Man Ray, Herbert Bayer, Edward and Brett Weston, Piet Zwart, Moholy-Nagy, Renger-Patzsch, Franz Roh, Paul Schuitema, Umbo and many others. A very good Japanese- bound softcover with soiling to the white pictorial wrappers and light wear near the margins. Spine head/heel chipped with paper loss and small tears and splits. Interior pages bright and binding tight. (#KC15855) $750.00 1 Toyen. Paris, 1953. May 1953, Galerie A L’ Etoile Scellee, 11, 3 Rue du Pre aux Clercs, Paris 1953. Ephemera, folded approx. -

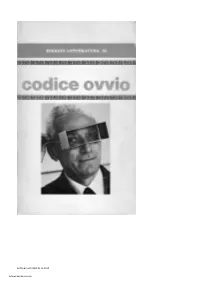

Bruno Munari: OBVIOUS CODE

BoTSL#15 2019 DEC 02 10:29 AM BoTSL#15 2020 APR 10 2:34 PM Bruno Munari: OBVIOUS CODE Previous issues of The Serving Library’s journals have been The volume closes with the translation of an essay by the late collections of individual “bulletins” loosely bound by a common Italian art critic and scholar Paolo Fossati, “For Obvious Code,” theme. This one is different: it comprises the first English which was originally included as a postscript to the book. translation of the late Italian polymath Bruno Munari’s Codice ovvio (Obvious code). The Italian original was published by Cover: The first edition, 1971 Einaudi in 1971, then republished by Corraini in 2017. We are hugely grateful to both publishers, and to the estate of Bruno Munari, for their permission and support. Munari’s work, approach, and demeanor have been a key influence on The Serving Library, and the idea of dedicating an entire issue of the journal to his work has been floating around for a while. Considering that half of our current editorial team is Italian, and half of that half is a professional translator, we settled on the idea of translating Codice ovvio, a modest portfolio of Munari’s work compiled by Munari himself. Importantly for us, it brings together his often overlooked writing about and around those works. For non-Italian readers, it is all too easy to glance at Munari’s paragraphs — or feed them to an online translator — and glean the sort of thing they probably say in view of captioning the work. -

Pages 6-7 Crippa, Lot 7 Pagine

LOT 32 In copertina | Cover Pagine 4-5 | Pages 4-5 Boetti, lot 28 Guttuso, lot 36 Retro copertina | Back cover Pagine 6-7 | Pages 6-7 Pagina 119 | Page 119 Baechler, lot 29 Crippa, lot 7 Simeti, lot 22 Pagina 1 | Page 1 Pagine 8-9 | Pages 8-9 Pagina 128 | Page 128 Adami, lot 32 Schifano, lot 46 Emblema, lot 45 SEDE - VIA SANT’AGNESE 18, 20123 MILANO ASTA ARTE MODERNA E CONTEMPORANEA 27 APRILE 2021 MILANO, VIA SANT’AGNESE 18 DAL 15 AL 26 APRILE, MILANO VIA SANT’AGNESE 18 0 (DA LUNEDÌ A SABATO - ORARIO 10.00-18.00) PREVIO APPUNTAMENTO UNICA SESSIONE MARTEDÌ 27 APRILE 2021 ORE 16.00 LOTTI 1 - 200 PRESENTAZIONE TELEVISIVA TOP LOTS Lunedì 19/4 ore 21.30-23 canale 135 del digitale terrestre + sky 821 Martedì 20/4 ore 21.30-23 canale 135 del digitale terrestre + sky 821 Giovedì 22/4 ore 21.30-23 canale 135 del digitale terrestre + sky 821 Venerdì 23/4 ore 21.30-23 canale 135 del digitale terrestre + sky 937 OFFERTE SCRITTE FINO A LUNEDÌ 26 APRILE 2021 ORE 15.00 FAX +39 02 40703717 [email protected] È possibile partecipare in diretta on-line inscrivendosi (almeno 24 ore prima) sul nostro sito www.ambrosianacasadaste.com CONSULTAZIONE CATALOGO E MODULISTICA www.ambrosianacasadaste.com da venerdì 2 aprile 2021 AMBROSIANA CASA D’ASTE / GALLERIA POLESCHI CASA D’ASTE - VIA SANT’AGNESE 18 20123 MILANO - TEL. +39 0289459708 - FAX +39 0240703717 www.ambrosianacasadaste.com • [email protected] LOT 36 338 1226703 5 MODERN AND CONTEMPORARY ART AUCTION APRIL 27th, 2021 MILANO, VIA SANT’AGNESE 18 APRIL 15th - APRIL 26th, MILAN, VIA SANT’AGNESE 18 (MONDAY TO SATURDAY - 10.00 AM-6.00 PM) BY APPOINTMENT ONLY ONE SESSION TUESDAY, APRIL 27th, 2021 - 4.00 PM LOTS 1 - 200 WRITTEN BIDS UNTIL MONDAY APRIL 26th 2021 - 3.00 PM FAX +39 02 40703717 [email protected] You can bid online by registering (at least 24 hours before the auction) on www.ambrosianacasadaste.com CATALOGUE AND FORMS AVAILABLE ON LINE www.ambrosianacasadaste.com from friday April 2nd 2021 AMBROSIANA CASA D’ASTE / GALLERIA POLESCHI CASA D’ASTE - VIA SANT’AGNESE 18 20123 MILANO - TEL. -

ITALIAN MODERN ART | ISSUE 3: ISSN 2640-8511 Introduction

ITALIAN MODERN ART | ISSUE 3: ISSN 2640-8511 Introduction ITALIAN MODERN ART - ISSUE 3 | INTRODUCTION italianmodernart.org/journal/articles/introduction-3 Raffaele Bedarida | Silvia Bignami | Davide Colombo Methodologies of Exchange: MoMA’s “Twentieth-Century Italian Art” (1949), Issue 3, January 2020 https://www.italianmodernart.org/journal/issues/methodologies-of- exchange-momas-twentieth-century-italian-art-1949/ ABSTRACT A brief overview of the third issue of Italian Modern Art dedicated to the MoMA 1949 exhibition Twentieth-Century Italian Art, including a literature review, methodological framework, and acknowledgments. If the study of artistic exchange across national boundaries has grown exponentially over the past decade as art historians have interrogated historical patterns, cultural dynamics, and the historical consequences of globalization, within such study the exchange between Italy and the United States in the twentieth-century has emerged as an exemplary case.1 A major reason for this is the history of significant migration from the former to the latter, contributing to the establishment of transatlantic networks and avenues for cultural exchange. Waves of migration due to economic necessity in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries gave way to the smaller in size but culturally impactful arrival in the U.S. of exiled Jews and political dissidents who left Fascist Italy during Benito Mussolini’s regime. In reverse, the presence in Italy of Americans – often participants in the Grand Tour or, in the 1950s, the so-called “Roman Holiday” phenomenon – helped to making Italian art, past and present, an important component in the formation of American artists and intellectuals.2 This history of exchange between Italy and the U.S. -

Impressionist & Modern

Impressionist & Modern Art New Bond Street, London I 28 February 2019 Impressionist & Modern Art New Bond Street, London I Thursday 28 February 2019, 5pm BONHAMS ENQUIRIES PHYSICAL CONDITION IMPORTANT INFORMATION 101 New Bond Street London OF LOTS IN THIS AUCTION The United States Government London W1S 1SR India Phillips PLEASE NOTE THAT THERE IS NO has banned the import of ivory bonhams.com Global Head of Department REFERENCE IN THIS CATALOGUE into the USA. Lots containing +44 (0) 20 7468 8328 TO THE PHYSICAL CONDITION OF ivory are indicated by the VIEWING [email protected] ANY LOT. INTENDING BIDDERS symbol Ф printed beside the Friday 22 February 10am – 5pm MUST SATISFY THEMSELVES AS lot number in this catalogue. Saturday 23 February 11am - 4pm Hannah Foster TO THE CONDITION OF ANY LOT Sunday 24 February 11am - 4pm Department Director AS SPECIFIED IN CLAUSE 14 PRESS ENQUIRIES Monday 25 February 10am - 5pm +44 (0) 20 7468 5814 OF THE NOTICE TO BIDDERS [email protected] Tuesday 26 February 10am - 5pm [email protected] CONTAINED AT THE END OF THIS Wednesday 27 February 10am - 5pm CATALOGUE. CUSTOMER SERVICES Thursday 28 February 10am - 3pm Ruth Woodbridge Monday to Friday Specialist As a courtesy to intending bidders, 8.30am to 6pm SALE NUMBER +44 (0) 20 7468 5816 Bonhams will provide a written +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 25251 [email protected] Indication of the physical condition of +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 Fax lots in this sale if a request is received CATALOGUE Aimée Honig up to 24 hours before the auction Please see back of catalogue £22.00 Junior Specialist starts. -

Spring 2020 Catalog (PDF)

Spring 2020 Adult / Children’s / Moleskine Books Paper + Goods Spring 2020 4 Natural Palettes 6 Cultivated: The Elements of Floral Style 8 Guide to Historic Artists’ Homes & Studios 10 The Little Gardener 12 Broadly Speaking 14 Not Now: The Procrastinator’s Manual 15 Graphic Design Rules 16 Paula Scher: Twenty-Five Years at the Public 18 This Is What Democracy Looked Like 19 A-frame 20 Tom Kundig: Working Title 22 The New Farm: Contemporary Rural Architecture 23 The Art of Earth Architecture: Past, Present, Future 24 Amherst College: The Campus Guide MOLESKINE BOOKS 26 Seymour Chwast: Inspiration and Process 27 Moleskine Books Recent Highlights 29 Selected Moleskine Books Backlist CHILDREN’S BOOKS 32 Little Cheetah’s Shadow 34 Malo and the Merry-Go-Round 35 My Bison 36 In the Garden 37 Inventive Animals: Sticker Activity Book 37 Streams and Ponds: Sticker Activity Book 40 Frank Lloyd Wright: Meet the Architect! 41 Selected Children’s Backlist PAPER + GOODS 44 Ex Libris: Fifty Postcards 45 Cultivated Notecards 46 Grids & Guides Eco Notebook 47 Sea Stamps 48 Little Notes: African Batik 48 Little Notes: Katazome 49 Virginia Woolf Notecards 50 Herbaria Notecards 51 Redstone Diary 2021: Everyday Pleasures 52 Selected Paper + Goods Backlist RECENT HIGHLIGHTS 62 Gift Books & Bestsellers 74 Selected Trade Backlist 92 Index 96 Ordering Information Forthcoming Titles A groundbreaking color resource for creatives Natural Palettes Inspiration from Plant-Based Color Sasha Duerr Visual & Renowned natural dyer, artist, and educator Sasha Duerr envisions a new age popular Culture of fresh, modern color palettes, drawing from our original source of inspiration — April 2020 and ingredients—the natural world around us. -

Bruno Munari Bruno Munari (1907 – 1998)

BRUNO MUNARI BRUNO MUNARI (1907 – 1998) Bruno Munari was an Italian artist and designer with wide-ranging skills. He worked as a painter, sculptor, and industrial designer, he was a graphic artist and filmmaker, a writer and a poet. Munari believed in the power of simple design to stimulate the imagination. Considered one of the greatest protagonists of art, design and graphics of the 20th century, always maintaining unchanged his whimsical creativity to support his constructive survey of form through visual and tactile experiments, and his great ability to communicate through words, objects, toys. FUTURISM AND USELESS MACHINES 1927 took part in the events of the second Futurism in Milan, participating in the collective of the Pesaro Gallery as well as the Venice Biennale and the Quadrennial in Rome and Paris in the thirties. 1933 he exhibited his "useless machines", mechanical devices studied for their aesthetic characteristics, presented as "experimental models to test the possibility of aesthetic information of visual language." From 1934 to 1936 he devoted himself to abstract painting. Arte Concreta and Arte Povera • In 1948, together with A. Soldiers, G. Monnet, G. Dorfles, he founded the MAC (Concrete Art Movement). In the fifties his research resumed with a series of "concave-convex sculptures" (1949-65), of paintings "positive- negative" (1951 onwards), of three-dimensional experimental models (Composition on the square; Travel Sculptures; Structures continuous), until the visual experiment obtained with polarized light (from 1953 onwards). • In the mid 1950s-’60s Munari was concurrently in Milan with Arte Povera artists such as Lucio Fontana and Piero Manzoni. Design As Art • Munari and many other Italian artists began to publish their ideas in journals, some which are still published, and to make art renegotiating the definition of the true artist as separate from an outmoded, elitist avant-gardism.