Wisconsin Magazine of History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wisconsin College Id Camp #2 July 10Th, 2021 Schedule

WISCONSIN COLLEGE ID CAMP #2 JULY 10TH, 2021 SCHEDULE 9:30 am – 9:55 am: Camp Registration 10:00 am – 11:45 am: Training Session 12:00 pm – 12:40 pm: Lunch (Please bring your own Lunch) 12:45 pm – 1:10 pm: Paula’s Presentation 1:15 pm – 2:30 pm: Group A: Athletic Facility Tour Group B: 11 vs. 11 Match 2:45 pm – 4:00 pm: Group B: Athletic Facility Tour Group A: 11 vs. 11 Match 4:00 pm: Camp Concludes WISCONSIN COLLEGE ID CAMP #2 MASTER Last Name First Name Grad Year Position: Training Group Adamski Kailey 2022 Goalkeeper Erin Scott A Awe Delaney 2025 Forward Tim Rosenfeld B Baczek Grace 2023 Defense Paula Wilkins A Bekx Sarah 2023 Defense Tim Rosenfeld B Bever Sonoma 2025 Forward Tim Rosenfeld B Beyersdorf Kamryn 2025 Midfield Tim Rosenfeld B Breunig McKenna 2025 Midfield Marisa Kresge B Brown Brooke 2023 Midfield Paula Wilkins A Chase Nicole 2025 Defense Tim Rosenfeld B Ciantar Elise 2022 Forward Marisa Kresge B Davis Abigail 2024 Midfield Tim Rosenfeld B Denk Sarah 2024 Defense Paula Wilkins A Desmarais Abigail 2023 Midfield Marisa Kresge A Duffy Eily 2025 Midfield Marisa Kresge B Dykstra Grace 2025 Midfield Tim Rosenfeld B Fredenhagen Alexia 2023 Defense Marisa Kresge A Gichner Danielle 2024 Defense Paula Wilkins A Guenther Eleanor 2026 Defense Tim Rosenfeld B Last Name First Name Grad Yr. Position: Training Group Hernandez ‐ Rahim Gabriella 2023 Forward Marisa Kresge A Hildebrand Peyton 2022 Defense Paula Wilkins A Hill Kennedy 2022 Defense Paula Wilkins A Hill Lauren 2025 Defense Paula Wilkins A Hoffmann Sophia 2022 Midfield Tim Rosenfeld -

AM IDEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS of the SENATE WARTIME ADDRESSES of ROBERT MARION LA FOLLETTE Harry R. Gianneschi a Dissertation Submitte

AM IDEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF THE SENATE WARTIME ADDRESSES OF ROBERT MARION LA FOLLETTE Harry R. Gianneschi A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December . 197.5 618206 Vu.w ii Wo • ABSTRACT Robert Marion La Follette, leading American progres sive, Governor of Wisconsin for three terms, and U. S. Senator from 1905 to 1925, was selected by the 1957 Senate as one of five of its greatest members throughout this country’s history. In light of Ij.s subsequent praiseworthy reputation and of the popular support he maintained during most of his career, the reason for his publicly denounced "anti-war" stance in 1917 has remained a mystery to many critics. Viewing the stance as a break-away from his previous beliefs, historians have tagged him as pacifistic, ignorant, or demagogic in his approach to the war. This study was designed to investigate elements in La Follette's life and speaking which could clarify the motivation for his Senate speeches from April 4 to October 6 in 1917. Research on this topic was devoted to an in-depth investigation of La Follette's entire speaking career. Texts of the speeches he gave during his life, editorial writings presented in La Follette's Magazine, and the personal papers of La Follette, members of his family, and close friends, all located in the Wisconsin State Histori cal Society Archives, were studied. Reactions were discovered in accounts by his contemporaries and the newspapers of the day. -

Talk Like a Badger

Talk Like a Badger Student Center A section of the UW’s website, which allows students to schedule If you feel like your student is speaking an entirely different language, classes, check grades and graduation requirements, and pay tuition bills. this UW vocabulary list can help. TA. Shout-Outs. ASM. Langdon. Huh? Center for Leadership and Involvement The CFLI offers students a variety of leadership programs, while also When your student first starts sprinkling these terms — and more encouraging them to get involved in the campus community through — during conversations, you may find yourself in need of a translator. student organizations, intramural sports, and volunteer activities. Along with other aspects of his or her new environment, your student has been learning a new vocabulary. And while it’s become second nature to your student, as a parent, you might need a little help. Student Traditions The Parent Program asked some students to make a list of com- Homecoming monly used words and phrases, and provide definitions. Now it’s time A week of events — typically in October — that celebrates everything for you to go into study mode and review the list below. Badger. A Homecoming Committee, with support from the Wisconsin Before you know it, you’ll be talking Badger, too. Alumni Association, coordinates special events that honor UW tradi- tions; any proceeds from events benefit the Dean of Students Crisis Academically Speaking Loan fund, which helps students with financial burdens. The week is capped off by a parade down State Street on Friday afternoon, with Schools and colleges the Homecoming football game on Saturday. -

Personnel Matters an Administrator’S Extended Leave Has UW’S Policies Under Scrutiny

DISPATCHES Personnel Matters An administrator’s extended leave has UW’s policies under scrutiny. Questions about a UW-Madison for an explanation. While administrative leave until the administrator’s extended leave expressing confidence that all investigation is complete. flared tensions between the university policies were fol- Coming in the middle of university and some state law- lowed in granting Barrows Wisconsin’s biennial state budget makers this summer, sparking leave, Wiley (who is Barrows’ deliberations, the case may have an investigation that may supervisor) agreed to appoint several lasting effects on the uni- affect how the university han- an independent investigator to versity. Lawmakers voted to cut dles personnel decisions. determine whether any of the UW-Madison’s budget by an The controversy involves a actions he or Barrows took additional $1 million because of leave of absence taken by Paul were inappropriate. Susan the controversy, and the Joint Barrows, the former vice chan- Steingass, a Madison attorney Legislative Audit Committee has cellor for student affairs. The and former Dane County Circuit now requested information on leave, for which Barrows used Court judge who teaches in the paid leaves and backup appoint- accumulated vacation and sick Law School, was designated to ments throughout the UW Sys- days, came after he acknowl- explore the matter and is tem to help it decide whether to edged a consensual relationship expected to report her findings launch a System-wide audit of with an adult graduate student. this fall to UW System President personnel practices. While not a violation of univer- Kevin Reilly and UW-Madison The UW Board of Regents sity policy, the revelation raised Provost Peter Spear. -

Nber Working Paper Series Henry Agard Wallace, The

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES HENRY AGARD WALLACE, THE IOWA CORN YIELD TESTS, AND THE ADOPTION OF HYBRID CORN Richard C. Sutch Working Paper 14141 http://www.nber.org/papers/w14141 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 June 2008 Thanks to Connie Chow and Hiroko Inoue for research assistance, to Susan B. Carter for critical advice, to Mason Gaffney for prodding questions that stimulated much further research, and to Norman Ellstrand for assistance with the plant biology. Financial support was provided by a National Science Foundation Grant: “Biocomplexity in the Environment, Dynamics of Coupled Natural and Human Systems.” Administrative support was provided by the Biotechnology Impacts Center and the Center for Economic and Social Policy at the University of California, Riverside. The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2008 by Richard C. Sutch. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Henry Agard Wallace, the Iowa Corn Yield Tests, and the Adoption of Hybrid Corn Richard C. Sutch NBER Working Paper No. 14141 June 2008 JEL No. N12 ABSTRACT This research report makes the following claims: 1] There was not an unambiguous economic advantage of hybrid corn over the open-pollinated varieties in 1936. -

A Brief History of Riverside Avenue

A Brief History of Riverside Avenue The following provides supplementary information for a walking tour of Marinette’s historic Riverside Avenue. It focuses on the development of the city and the residents of Riverside Avenue in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The information below begins with the house at 1851 Riverside and proceeds upriver to the Hattie Street bridge. The return leg of the tour includes information on the monuments along the river, followed by the Stephenson Public Library and ending at the Best Western Riverfront Inn (adjacent to 1851 Riverside). (Note: Click any picture below for a larger version of the image) Overview – Beginning in the 1880s, the region between Hall Avenue and the Menominee River (west of the downtown) became the site of some of the more fashionable residences in Marinette. Until 1890, most residential streets were built paralleling Main Street east of the downtown. Those streets were located near the sawmills and were populated primarily by sawmill laborers. The affluent members of the emerging business and professional community built their homes west of the downtown. Riverside Avenue (originally part of Main Street, renamed River Street by 1887, and Riverside Avenue by 1895) was the most affluent street in this new area and is composed of the residences of many of the most prominent individuals in the history of Marinette. Residences found in this neighborhood reflect popular architectural trends of the time unlike the vernacular houses found throughout the city. Marinette’s legacy as a late-nineteenth century lumber boom town remains with us today. 1851 Riverside, today Address: 1851 Riverside Built: Prior to 1881 (c. -

La Follette and the Progressive Machine in Wisconsin Robert S

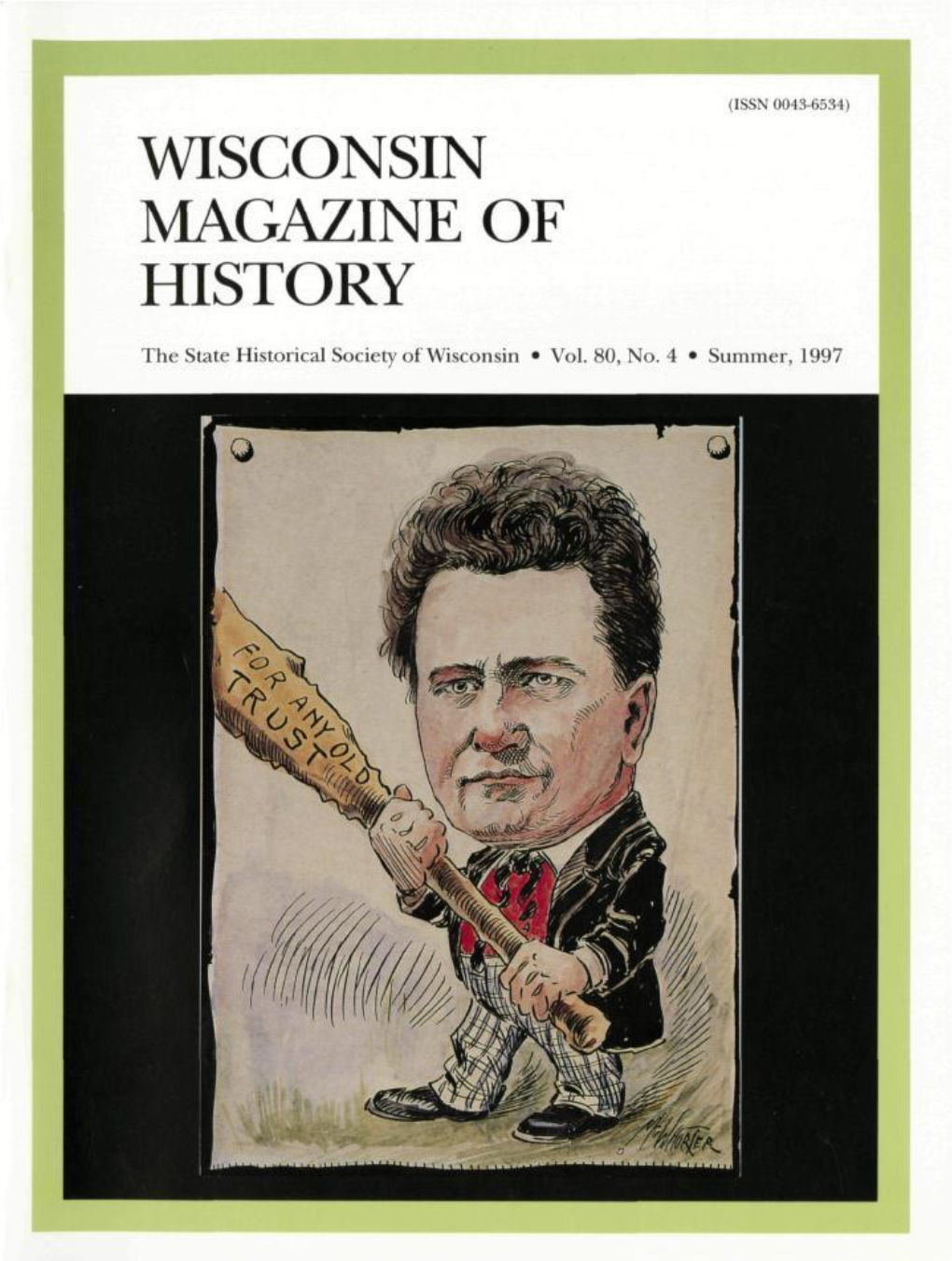

La Follette and the Progressive Machine in Wisconsin Robert S. Maxwell* To most people interested in history or government the study of political machines has held a peculiar fascination. Since the days of Lincoln Skffens and his fellow “Muck- rakers” the word “machine” has connoted sordid politics, graft, and the clever political manipulations of a “BOSS”Wil- liam M. Tweed or Mayor Frank Hague. In contrast, most re- form movements have been amateurish and unstable efforts which usually broke up in failure after one or two elections. On those rare occasions when successful reform organizations have been welded together they have developed techniques of political astuteness, leadership, and discipline not unlike the traditional machines. Such organizations have, in truth, been political machines, but with the difference that they operated in the public interest and for the public good. Certainly one of the most successful and dramatic of such state political reform organizations in recent history was that of Robert M. La Follette, Sr. and his fellow Progressives in Wisconsin during the years from 1900 to 1914. Here the Pro- gressives developed a powerful political machine, dominated state elections for a dozen years, and enacted a series of sweep- ing political, economic, and social reforms which attracted the attention of the entire nation and were widely copied. The personal success of La Follette, himself, was even more spec- tacular. From 1900 until his death in 1925 the voters of Wis- consin bestowed upon him every office that he sought:-three terms as governor, four terms as United States Senator, and on two occasions, the vote of the state for president. -

How Did Belle La Follette Resist Racial Segregation in Washington D.C., 1913-1914?

Santa Clara University Scholar Commons History College of Arts & Sciences 6-2004 How did Belle La Follette Resist Racial Segregation in Washington D.C., 1913-1914? Nancy Unger Santa Clara University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.scu.edu/history Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Political History Commons, Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons, Social History Commons, Social Justice Commons, United States History Commons, and the Women's History Commons Recommended Citation Unger, N. (2004) How did Belle La Follette Resist Racial Segregation in Washington D.C., 1913-1914? In K. Sklar and T. Dublin (Eds.) Women and Social Movements in the United States, 1775-2000, 8, no. 2. New York: Alexander Street Press. Copyright © 2004 Thomas Dublin, Kathryn Kish Sklar and Alexander Street Press, LLC. Reprinted with permission. Any future reproduction requires permission from original copyright holders. http://asp6new.alexanderstreet.com/tinyurl/tinyurl.resolver.aspx?tinyurl=3CPQ This Other is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts & Sciences at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in History by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. How Did Belle La Follette Oppose Racial Segregation in Washington, D.C., 1913-1914? Abstract Beginning in 1913, progressive reformer Belle Case La Follette wrote a series of articles for the "women's page" of her family's magazine, denouncing the sudden racial segregation in several departments of the federal government. Those articles reveal progressive efforts to appeal specifically to women to combat injustice, and also demonstrate the ability of women to voice important political opinions prior to suffrage. -

![CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8733/chairmen-of-senate-standing-committees-table-5-3-1789-present-978733.webp)

CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present

CHAIRMEN OF SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–present INTRODUCTION The following is a list of chairmen of all standing Senate committees, as well as the chairmen of select and joint committees that were precursors to Senate committees. (Other special and select committees of the twentieth century appear in Table 5-4.) Current standing committees are highlighted in yellow. The names of chairmen were taken from the Congressional Directory from 1816–1991. Four standing committees were founded before 1816. They were the Joint Committee on ENROLLED BILLS (established 1789), the joint Committee on the LIBRARY (established 1806), the Committee to AUDIT AND CONTROL THE CONTINGENT EXPENSES OF THE SENATE (established 1807), and the Committee on ENGROSSED BILLS (established 1810). The names of the chairmen of these committees for the years before 1816 were taken from the Annals of Congress. This list also enumerates the dates of establishment and termination of each committee. These dates were taken from Walter Stubbs, Congressional Committees, 1789–1982: A Checklist (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1985). There were eleven committees for which the dates of existence listed in Congressional Committees, 1789–1982 did not match the dates the committees were listed in the Congressional Directory. The committees are: ENGROSSED BILLS, ENROLLED BILLS, EXAMINE THE SEVERAL BRANCHES OF THE CIVIL SERVICE, Joint Committee on the LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, LIBRARY, PENSIONS, PUBLIC BUILDINGS AND GROUNDS, RETRENCHMENT, REVOLUTIONARY CLAIMS, ROADS AND CANALS, and the Select Committee to Revise the RULES of the Senate. For these committees, the dates are listed according to Congressional Committees, 1789– 1982, with a note next to the dates detailing the discrepancy. -

Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System Agenda

Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System Office of the Secretary 1860 Van Hise Hall Madison, Wisconsin 53706 (608)262-2324 October 29 2003 TO: Each Regent FROM: Judith A. Temby RE: Agendas and supporting documents for meetings of the Board and Committees to be held Thursday at The Lowell Center, 610 Langdon St. and Friday at 1820 Van Hise Hall, 1220 Linden St., Madison on November 6 and 7, 2003. Thursday, November 6, 2003 10:00 a.m. - 12:30 p.m. - Regent Study Groups • Revenue Authority and Other Opportunities, Lowell Center, Lower Lounge • Achieving Operating Efficiencies, Lowell Center, room B1A • Re-Defining Educational Quality, Lowell Center room B1B • The Research and Public Service Mission, State Capitol • Our Partnership with the State, Lowell Center, room 118 12:30 - 1:00 p.m. - Lunch, Lowell Center, Lower Level Dinning room 1:00 p.m. - Board of Regents Meeting on UW System and Wisconsin Technical College System Credit Transfer Lowell Center, room B1A/B1B 2:00 p.m. – Committee meetings: Education Committee Lowell Center, room 118 Business and Finance Committee Lowell Center, room B1A/B1B Physical Planning and Funding Committee Lowell Center, Lower Lounge 3:30 p.m. - Public Investment Forum Lowell Center, room B1A/B1B Friday, November 7, 2003 9:00 a.m. - Board of Regents 1820 Van Hise Hall Persons wishing to comment on specific agenda items may request permission to speak at Regent Committee meetings. Requests to speak at the full Board meeting are granted only on a selective basis. Requests to speak should be made in advance of the meeting and should be communicated to the Secretary of the Board at the above address. -

Of Agriculture

NAL DIGITIZING PROJECT MBP0000254 GENTURY SERVieE the first 100 years of THE UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE USDA HISTORY COLLECTION^ BOX__~r__ FOLDER __rä Tí n * merica's Strength . Agricultural Abundance CENTURY OF SERVICE the first 100 years of THE UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE AUTHORS Gladys L. Baker Wayne D. Rasmussen Vivian Wiser Jane M. Porter ECONOMIC RESEARCH SERVICE Agricultural History Branch CENTURY OF SERVICE the first 100 years of THE UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE CENTENNIAL COMMITTEE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE Growth Through Agricultural Progress COMMITTEE ON AGRICULTURAL HISTORY The Committee on Agricultural History was appointed by the Secretary of Agriculture in Memorandum 1440, to give direc- tion and leadership to a study necessary to the preparation of a history commemorating the Centennial of the United States Department of Agriculture, to establish policies and standards applicable to such a publication, and to provide guidance in its development. Membership of the Committee is: Nathan M. Koffsky, Administrator, Economic Research Service (Chairman). Oris V. Wells, Served as Chairman prior to his retirement as Administrator, Agricultural Marketing Service. R. Lyle Webster, Director of Information. Foster E. Mohrhardt, Director of the National Agricultural Library. James P. Cavin, Economic Research Service (Secretary). IV FOREWORD ORVILLE L. FREEMAN Secretary of Agriculture Agriculture in the United States has progressed from an economy of scarcity to an economy of abundance in the space of a hundred years. This profound change may be measured in a number of ways. For example, less than 9 percent of our labor force is engaged in agriculture today, as compared with 20 to 40 percent in much of Western Europe, over 45 percent in the Soviet Union, and 70 to 80 percent in some parts of the world. -

Congressional Record-Sen Ate

18 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-SENATE. }fARcH -15, Second Lieut. Guy H .. Wyman, Eleventh Cavalry, to be first M.ESSAGE FR-OM THE PRESIDENT. lieutenant from March 10; 1913, yice First Lieut. John P. Has son~ Sixth Cavalry, promoted. A message in writing from the PreSid~t of the United .States was communicated to the Senate by · l\Ir. · Latta, one of his CORPS OF ENGINEERS. secretaries. Capt. 'Michael J. McDonough, Corps of Engineers, to be major STATEMENT OF APPROP~IA.TIONS . from February 27, 1913, vice Maj. Chester Jiarding, promoted. Mr. WARREN. Mr. President, I rise to ask unanimous con First Lieut. Harold S. Hetrick, Corps of Engineers, to be sent to print certain matter in the RECORD. I may say in ex captain from February 27, 1913, vice Capt. Michael J. Mc planation that it is usual for the Committees on Appropriations Donough, promoted. of the House and Senate to .submit on the last day of the sessjon First Lieut. William A. Johnson, Corps of Engineers, to be a statement giving a history of the appropriation bills und the captain from February 28, 1913, vice Capt. Edward M. Adams, sum total of the appropriations, also the estimates from the retired from active service February 27, 1913. departments and the amounts at the various stages ·Of progress APPOINTM.ENTS IN THE ARMY. of the bills-amounts of the bills as brought into the House and MEDICAL RESERVE CORPS. voted upon there, and as they came to the Senate, and so forth. The stress of business near the close of the last session of the To be fi1·st lieutenants with rank from Ma.1·ch.