Full Article on Fort Clay with Additional Maps and Garrison Information

Total Page:16

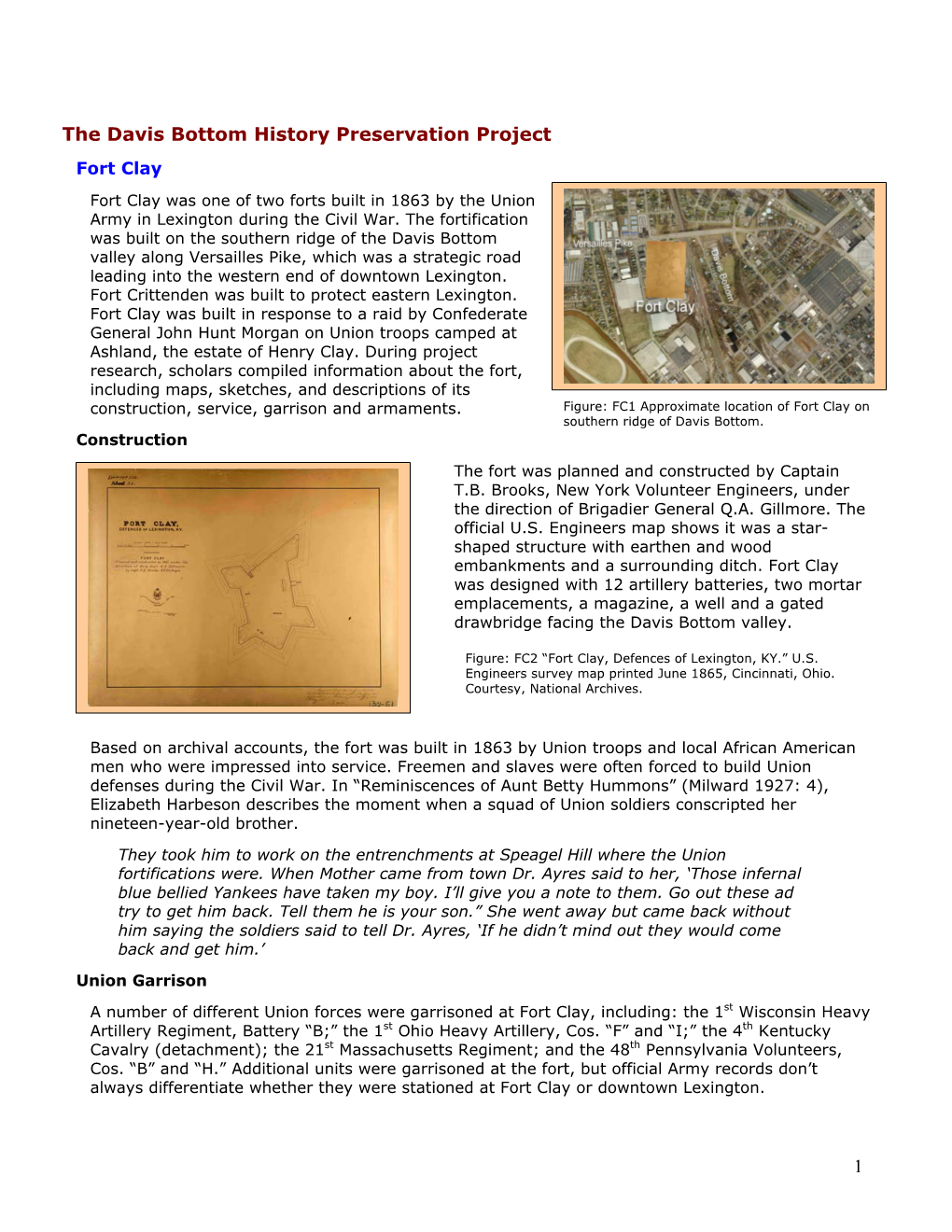

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brochure Design by Communication Design, Inc., Richmond, VA 877-584-8395 Cheatham Co

To Riggins Hill CLARKSVILLE MURFREESBORO and Fort Defiance Scroll flask and .36 caliber Navy Colt bullet mold N found at Camp Trousdale . S P R site in Sumner County. IN G Stones River S T Courtesy Pat Meguiar . 41 National Battlefield The Cannon Ball House 96 and Cemetery in Blountville still 41 Oaklands shows shell damage to Mansion KNOXVILLE ST. the exterior clapboard LEGE Recapture of 441 COL 231 Evergreen in the rear of the house. Clarksville Cemetery Clarksville 275 40 in the Civil War Rutherford To Ramsey Surrender of ST. County Knoxville National Cemetery House MMERCE Clarksville CO 41 96 Courthouse Old Gray Cemetery Plantation Customs House Whitfield, Museum Bradley & Co. Knoxville Mabry-Hazen Court House House 231 40 “Drawing Artillery Across the Mountains,” East Tennessee Saltville 24 Fort History Center Harper’s Weekly, Nov. 21, 1863 (Multiple Sites) Bleak House Sanders Museum 70 60 68 Crew repairing railroad Chilhowie Fort Dickerson 68 track near Murfreesboro 231 after Battle of Stones River, 1863 – Courtesy 421 81 Library of Congress 129 High Ground 441 Abingdon Park “Battle of Shiloh” – Courtesy Library of Congress 58 41 79 23 58 Gen. George H. Thomas Cumberland 421 Courtesy Library of Congress Gap NHP 58 Tennessee Capitol, Nashville, 1864 Cordell Hull Bristol Courtesy Library of Congress Adams Birthplace (East Hill Cemetery) 51 (Ft. Redmond) Cold Spring School Kingsport Riggins Port Royal Duval-Groves House State Park Mountain Hill State Park City 127 (Lincoln and the 33 Blountville 79 Red Boiling Springs Affair at Travisville 431 65 Portland Indian Mountain Cumberland Gap) 70 11W (See Inset) Clarksville 76 (Palace Park) Clay Co. -

Kentucky in the 1880S: an Exploration in Historical Demography Thomas R

The Kentucky Review Volume 3 | Number 2 Article 5 1982 Kentucky in the 1880s: An Exploration in Historical Demography Thomas R. Ford University of Kentucky Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/kentucky-review Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits you. Recommended Citation Ford, Thomas R. (1982) "Kentucky in the 1880s: An Exploration in Historical Demography," The Kentucky Review: Vol. 3 : No. 2 , Article 5. Available at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/kentucky-review/vol3/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Kentucky Libraries at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Kentucky Review by an authorized editor of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Kentucky in the 1880s: An Exploration in Historical Demography* e c Thomas R. Ford r s F t.; ~ The early years of a decade are frustrating for social demographers t. like myself who are concerned with the social causes and G consequences of population changes. Social data from the most recent census have generally not yet become available for analysis s while those from the previous census are too dated to be of current s interest and too recent to have acquired historical value. That is c one of the reasons why, when faced with the necessity of preparing c a scholarly lecture in my field, I chose to stray a bit and deal with a historical topic. -

Captain Thomas Jones Gregory, Guerrilla Hunter

Captain Thomas Jones Gregory, Guerrilla Hunter Berry Craig and Dieter Ullrich Conventional historical wisdom long held that guerrilla warfare had little effect on the outcome of America's most lethal conflict. Hence, for years historians expended relatively Little ink on combat between these Confederate marauders and their foes-rear-area Union troops, state militia and Home Guards. But a handful of historians, including Daniel Sutherland, now maintain that guerrilla warfare, most brutal and persistent in border state Missouri and Kentucky, was anything but an adjunct to the wider war. "It is impossible to understand the Civil War without appreciating the scope and impact of the guerrilla conflict," Sutherland argued in A Savage Confl,ict: The Decisive Role of Guerrillas in the Civil War (2009). "That is no easy thing to do," he conceded, because guerrilla warfare was "intense and sprawling, born in controversy, and defined by all variety of contradictions, contours, and shadings." 1 Mao Zedong, the founder of the People's Republic of China, is arguably the most famous and most successful guerrilla leader in history. "Many people think it impossible for guerrillas to exist for long in the enemy's rear," he wrote in 193 7 while fighting Japanese invaders. "Such a belief reveals lack of comprehension of the relationship that should exist between the people and the troops. The former may be likened to water the latter to the fish who inhabit it. "2 Guerrilla "fish" plagued occupying Union forces in the Jackson Purchase, Kentucky's westernmost region, for most of the war because the "water" was welcoming. -

John Hunt Morgan's Christmas Raid by Tim Asher in December 1862

John Hunt Morgan’s Christmas Raid By Tim Asher In December 1862, the rebel army was back in Tennessee after the Confederate disappointment at Perryville, Kentucky. The Confederates found themselves under constant pressure from the growing Union presence in Tennessee commanded by Gen. William Rosecrans. All indications were that the Union General was planning a winter campaign as soon as adequate supplies were collected at Nashville. The Confederate commander of the Army of Tennessee General Braxton Bragg understood his situation and was determined to stop the flow of war materials into Nashville as best he could. To do this, he called upon his newly promoted brigadier general and Kentucky native John Hunt Morgan to break Rosecrans’ L&N supply line somewhere in Kentucky. The L&N railroad carried food, forage, and supplies from Louisville through the uneven terrain of Kentucky to the Union army’s depot at Nashville. Reports were that the L&N tracks were heavily guarded to prepare for the push on Bragg. But an ever confident Morgan believed that, regardless of the fortifications, a weakness could be found just north of Elizabethtown in an area know generally as Muldraugh’s hill. Muldraugh’s hill is an escarpment rising from the Ohio River to an elevation of over 400 feet in just five miles and crisscrossed by streams and gorges. Morgan’s knowledge of the area probably came from the Brigadier General John experience of his brother-in-law and second in command, Hunt Morgan, CSA Colonel Basil Duke who in 1861 had walked through the area avoiding Federal capture in Elizabethtown. -

East and Central Farming and Forest Region and Atlantic Basin Diversified Farming Region: 12 Lrrs N and S

East and Central Farming and Forest Region and Atlantic Basin Diversified Farming Region: 12 LRRs N and S Brad D. Lee and John M. Kabrick 12.1 Introduction snowfall occurs annually in the Ozark Highlands, the Springfield Plateau, and the St. Francois Knobs and Basins The central, unglaciated US east of the Great Plains to the MLRAs. In the southern half of the region, snowfall is Atlantic coast corresponds to the area covered by LRR N uncommon. (East and Central Farming and Forest Region) and S (Atlantic Basin Diversified Farming Region). These regions roughly correspond to the Interior Highlands, Interior Plains, 12.2.2 Physiography Appalachian Highlands, and the Northern Coastal Plains. The topography of this region ranges from broad, gently rolling plains to steep mountains. In the northern portion of 12.2 The Interior Highlands this region, much of the Springfield Plateau and the Ozark Highlands is a dissected plateau that includes gently rolling The Interior Highlands occur within the western portion of plains to steeply sloping hills with narrow valleys. Karst LRR N and includes seven MLRAs including the Ozark topography is common and the region has numerous sink- Highlands (116A), the Springfield Plateau (116B), the St. holes, caves, dry stream valleys, and springs. The region also Francois Knobs and Basins (116C), the Boston Mountains includes many scenic spring-fed rivers and streams con- (117), Arkansas Valley and Ridges (118A and 118B), and taining clear, cold water (Fig. 12.2). The elevation ranges the Ouachita Mountains (119). This region comprises from 90 m in the southeastern side of the region and rises to 176,000 km2 in southern Missouri, northern and western over 520 m on the Springfield Plateau in the western portion Arkansas, and eastern Oklahoma (Fig. -

Civil War Generals Buried in Spring Grove Cemetery by James Barnett

Spring Grove Cemetery, once characterized as blending "the elegance of a park with the pensive beauty of a burial-place," is the final resting- place of forty Cincinnatians who were generals during the Civil War. Forty For the Union: Civil War Generals Buried in Spring Grove Cemetery by James Barnett f the forty Civil War generals who are buried in Spring Grove Cemetery, twenty-three had advanced from no military experience whatsoever to attain the highest rank in the Union Army. This remarkable feat underscores the nature of the Northern army that suppressed the rebellion of the Confed- erate states during the years 1861 to 1865. Initially, it was a force of "inspired volunteers" rather than a standing army in the European tradition. Only seven of these forty leaders were graduates of West Point: Jacob Ammen, Joshua H. Bates, Sidney Burbank, Kenner Garrard, Joseph Hooker, Alexander McCook, and Godfrey Weitzel. Four of these seven —Burbank, Garrard, Mc- Cook, and Weitzel —were in the regular army at the outbreak of the war; the other three volunteered when the war started. Only four of the forty generals had ever been in combat before: William H. Lytle, August Moor, and Joseph Hooker served in the Mexican War, and William H. Baldwin fought under Giuseppe Garibaldi in the Italian civil war. This lack of professional soldiers did not come about by chance. When the Constitutional Convention met in Philadelphia in 1787, its delegates, who possessed a vast knowledge of European history, were determined not to create a legal basis for a standing army. The founding fathers believed that the stand- ing armies belonging to royalty were responsible for the endless bloody wars that plagued Europe. -

A Study of Migration from Augusta County, Virginia, to Kentucky, 1777-1800

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1987 "Peopling the Western Country": A Study of Migration from Augusta County, Virginia, to Kentucky, 1777-1800 Wendy Sacket College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Sacket, Wendy, ""Peopling the Western Country": A Study of Migration from Augusta County, Virginia, to Kentucky, 1777-1800" (1987). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625418. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-ypv2-mw79 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "PEOPLING THE WESTERN COUNTRY": A STUDY OF MIGRATION FROM AUGUSTA COUNTY, VIRGINIA, TO KENTUCKY, 1777-1800 A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Wendy Ellen Sacket 1987 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Author Approved, December, 1987 John/Se1by *JU Thad Tate ies Whittenburg i i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.............................. iv LIST OF T A B L E S ...............................................v LIST OF MAPS . ............................................. vi ABSTRACT................................................... v i i CHAPTER I. AN INTRODUCTION TO THE LITERATURE, PURPOSE, AND ORGANIZATION OF THE PRESENT STUDY . -

Some Revolutionary War Soldiers Buried in Kentucky

Vol. 41, No. 2 Winter 2005 kentucky ancestors genealogical quarterly of the Perryville Casualty Pink Things: Some Revolutionary Database Reveals A Memoir of the War Soldiers Buried True Cost of War Edwards Family of in Kentucky Harrodsburg Vol. 41, No. 2 Winter 2005 kentucky ancestors genealogical quarterly of the Thomas E. Stephens, Editor kentucky ancestors Dan Bundy, Graphic Design Kent Whitworth, Director James E. Wallace, Assistant Director administration Betty Fugate, Membership Coordinator research and interpretation Nelson L. Dawson, Team Leader management team Kenneth H. Williams, Program Leader Doug Stern, Walter Baker, Lisbon Hardy, Michael Harreld, Lois Mateus, Dr. Thomas D. Clark, C. Michael Davenport, Ted Harris, Ann Maenza, Bud Pogue, Mike Duncan, James E. Wallace, Maj. board of Gen. Verna Fairchild, Mary Helen Miller, Ryan trustees Harris, and Raoul Cunningham Kentucky Ancestors (ISSN-0023-0103) is published quarterly by the Kentucky Historical Society and is distributed free to Society members. Periodical postage paid at Frankfort, Kentucky, and at additional mailing offices. Postmas- ter: Send address changes to Kentucky Ancestors, Kentucky Historical Society, 100 West Broadway, Frankfort, KY 40601-1931. Please direct changes of address and other notices concerning membership or mailings to the Membership De- partment, Kentucky Historical Society, 100 West Broadway, Frankfort, KY 40601-1931; telephone (502) 564-1792. Submissions and correspondence should be directed to: Tom Stephens, editor, Kentucky Ancestors, Kentucky Histori- cal Society, 100 West Broadway, Frankfort, KY 40601-1931. The Kentucky Historical Society, an agency of the Commerce Cabinet, does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, age, religion, or disability, and provides, on request, reasonable accommodations, includ- ing auxiliary aids and services necessary to afford an individual with a disability an equal opportunity to participate in all services, programs, and activities. -

Tennessee Civil War Trails Program 213 Newly Interpreted Marker

Tennessee Civil War Trails Program 213 Newly Interpreted Markers Installed as of 6/9/11 Note: Some sites include multiple markers. BENTON COUNTY Fighting on the Tennessee River: located at Birdsong Marina, 225 Marina Rd., Hwy 191 N., Camden, TN 38327. During the Civil War, several engagements occurred along the strategically important Tennessee River within about five miles of here. In each case, cavalrymen engaged naval forces. On April 26, 1863, near the mouth of the Duck River east of here, Confederate Maj. Robert M. White’s 6th Texas Rangers and its four-gun battery attacked a Union flotilla from the riverbank. The gunboats Autocrat, Diana, and Adams and several transports came under heavy fire. When the vessels drove the Confederate cannons out of range with small-arms and artillery fire, Union Gen. Alfred W. Ellet ordered the gunboats to land their forces; signalmen on the exposed decks “wig-wagged” the orders with flags. BLOUNT COUNTY Maryville During the Civil War: located at 301 McGee Street, Maryville, TN 37801. During the antebellum period, Blount County supported abolitionism. In 1822, local Quakers and other residents formed an abolitionist society, and in the decades following, local clergymen preached against the evils of slavery. When the county considered secession in 1861, residents voted to remain with the Union, 1,766 to 414. Fighting directly touched Maryville, the county seat, in August 1864. Confederate Gen. Joseph Wheeler’s cavalrymen attacked a small detachment of the 2nd Tennessee Infantry (U.S.) under Lt. James M. Dorton at the courthouse. The Underground Railroad: located at 503 West Hill Ave., Friendsville, TN 37737. -

The Political Process in Kentucky

Kentucky Law Journal Volume 45 | Issue 3 Article 1 1957 The olitP ical Process in Kentucky Jasper Shannon University of Kentucky Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj Part of the Law and Politics Commons, and the State and Local Government Law Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits you. Recommended Citation Shannon, Jasper (1957) "The oP litical Process in Kentucky," Kentucky Law Journal: Vol. 45 : Iss. 3 , Article 1. Available at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj/vol45/iss3/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kentucky Law Journal by an authorized editor of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Political Process in Kentucky By JASPER SHANNON* CircumstancesPeculiar to Kentucky The roots of law are deeply embedded in politics. Nowhere is this more true than in Kentucky. Law frequently is the thin veneer which reason employs in a ceaseless but unsuccessful effort to control the turbulence of emotion. Born in the troubled era of the American and French Revolutions, Kentucky was in addition exposed to four years of bitter civil violence when nationalism and sectionalism struggled for supremacy (1861-65). Kentucky, ac- cordingly, within her borders has known in its most intense form the heat of passion which so often supplants reason in the clash of interests forming the heart of legal and political processes. Too many times in its colorful history the forms of law have broken down in the conflict of emotions. -

A Native History of Kentucky

A Native History Of Kentucky by A. Gwynn Henderson and David Pollack Selections from Chapter 17: Kentucky in Native America: A State-by-State Historical Encyclopedia edited by Daniel S. Murphree Volume 1, pages 393-440 Greenwood Press, Santa Barbara, CA. 2012 1 HISTORICAL OVERVIEW As currently understood, American Indian history in Kentucky is over eleven thousand years long. Events that took place before recorded history are lost to time. With the advent of recorded history, some events played out on an international stage, as in the mid-1700s during the war between the French and English for control of the Ohio Valley region. Others took place on a national stage, as during the Removal years of the early 1800s, or during the events surrounding the looting and grave desecration at Slack Farm in Union County in the late 1980s. Over these millennia, a variety of American Indian groups have contributed their stories to Kentucky’s historical narrative. Some names are familiar ones; others are not. Some groups have deep historical roots in the state; others are relative newcomers. All have contributed and are contributing to Kentucky's American Indian history. The bulk of Kentucky’s American Indian history is written within the Commonwealth’s rich archaeological record: thousands of camps, villages, and town sites; caves and rockshelters; and earthen and stone mounds and geometric earthworks. After the mid-eighteenth century arrival of Europeans in the state, part of Kentucky’s American Indian history can be found in the newcomers’ journals, diaries, letters, and maps, although the native voices are more difficult to hear. -

![1 [De Fontaine, F. G.] Marginalia, Or, Gleanings from an Army Note-Book](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2674/1-de-fontaine-f-g-marginalia-or-gleanings-from-an-army-note-book-1402674.webp)

1 [De Fontaine, F. G.] Marginalia, Or, Gleanings from an Army Note-Book

[De Fontaine, F. G.] Marginalia, Or, Gleanings from an Army Note-Book Columbia, S. C.: Press of F. G. De Fontaine, 1864. Correspondence of “Personne” of the Charleston Courier Piety of southern leaders compared to northerners, 1, 3-4 Contrast between Yankees and southerners according to a Frenchman, 2-3 Heroes and bravery, 4-5 Robert E. Lee, 5-6 First Manassas, 6, 9 Stonewall Jackson, 7-8 Hatred by southern women, 8 Revolutionary father, 8-9 Officers, gentlemen, 9 Stonewall Jackson and religion, 9-10 Western Virginia mountaineers, 10-11 Loyal slave, 11-12, 16, 23 Federal and Confederate Generals, 12 Turks and Yankees, 12 Pillaging, 12-13 John Hunt Morgan, 13-14 Murfreesboro, 14-15 Brave Confederate, 15 Davis, Beauregard, 17 Child and Confederate loyalty, 17 Yankee soldiers and woman, 17 Alcohol, 17-18 Barbarous northern generals, Butler, McNeill, Milroy, Steinwehr, 18-19 Slave, 20 Fredericksburg, 20-21 Yankee and Robert E. Lee, 21 Patriotic ministers, 22 Women nurses, 23-24 Woman and Confederate soldier, 24 Beauregard praises a private, 24-25 Women and patriotism, 25 Abraham and Mary Lincoln, 25-26 Jefferson Davis and his children, 27-28 Heroism of soldiers, 28-29 Gaines’ Mill, 29 Yankees and women prisoners, 30-31 General Steinwehr, 31-33 Old volunteers, 33 Williamsburg, young hero, 33 Albert Sidney Johnston, 33-34 General Pettigrew, 34 John C. Breckinridge, 34 Death of General Garland, 34-35 1 Battle of Jackson, 35 Brave Death, 35-39 General speeches, 39 Outrages on women, 40 Brandy Station, 40-41 Brave attack, 41-42 Stonewall Jackson,