Captain Thomas Jones Gregory, Guerrilla Hunter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kentucky in the 1880S: an Exploration in Historical Demography Thomas R

The Kentucky Review Volume 3 | Number 2 Article 5 1982 Kentucky in the 1880s: An Exploration in Historical Demography Thomas R. Ford University of Kentucky Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/kentucky-review Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits you. Recommended Citation Ford, Thomas R. (1982) "Kentucky in the 1880s: An Exploration in Historical Demography," The Kentucky Review: Vol. 3 : No. 2 , Article 5. Available at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/kentucky-review/vol3/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Kentucky Libraries at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Kentucky Review by an authorized editor of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Kentucky in the 1880s: An Exploration in Historical Demography* e c Thomas R. Ford r s F t.; ~ The early years of a decade are frustrating for social demographers t. like myself who are concerned with the social causes and G consequences of population changes. Social data from the most recent census have generally not yet become available for analysis s while those from the previous census are too dated to be of current s interest and too recent to have acquired historical value. That is c one of the reasons why, when faced with the necessity of preparing c a scholarly lecture in my field, I chose to stray a bit and deal with a historical topic. -

East and Central Farming and Forest Region and Atlantic Basin Diversified Farming Region: 12 Lrrs N and S

East and Central Farming and Forest Region and Atlantic Basin Diversified Farming Region: 12 LRRs N and S Brad D. Lee and John M. Kabrick 12.1 Introduction snowfall occurs annually in the Ozark Highlands, the Springfield Plateau, and the St. Francois Knobs and Basins The central, unglaciated US east of the Great Plains to the MLRAs. In the southern half of the region, snowfall is Atlantic coast corresponds to the area covered by LRR N uncommon. (East and Central Farming and Forest Region) and S (Atlantic Basin Diversified Farming Region). These regions roughly correspond to the Interior Highlands, Interior Plains, 12.2.2 Physiography Appalachian Highlands, and the Northern Coastal Plains. The topography of this region ranges from broad, gently rolling plains to steep mountains. In the northern portion of 12.2 The Interior Highlands this region, much of the Springfield Plateau and the Ozark Highlands is a dissected plateau that includes gently rolling The Interior Highlands occur within the western portion of plains to steeply sloping hills with narrow valleys. Karst LRR N and includes seven MLRAs including the Ozark topography is common and the region has numerous sink- Highlands (116A), the Springfield Plateau (116B), the St. holes, caves, dry stream valleys, and springs. The region also Francois Knobs and Basins (116C), the Boston Mountains includes many scenic spring-fed rivers and streams con- (117), Arkansas Valley and Ridges (118A and 118B), and taining clear, cold water (Fig. 12.2). The elevation ranges the Ouachita Mountains (119). This region comprises from 90 m in the southeastern side of the region and rises to 176,000 km2 in southern Missouri, northern and western over 520 m on the Springfield Plateau in the western portion Arkansas, and eastern Oklahoma (Fig. -

741.5 June 2018 — No. Eighteen

MEANWHILE 741.5 JUNE 2018 — NO. EIGHTEEN Aline Kominsky-Crumb Ho Che Anderson Kominsky Che Guevara Aline Ho Chi Minh Anderson Rob- ert Crumb Komin- Gilbert sky-Crumb Hernandez Joe Pruett Jim Starlin Brian Az- zarello Phil Hester Michael Gaydos Mike Carey 741.5 COLLECTIONS I’d forgotten that Jack “King” Kirby had drawn Deadman. But yeah, he did, slapping that astral avenger smack dab in the middle of the Forever People. Said quintet of space hippies were the junior partners in Kirby’s Fourth World saga. Published by DC in the early 1970s, it was an epic that sprawled across four titles. In those comics, Kirby’s indefatigable imagination spun off one amazing character after another. The least of these was Forager. Introduced in New Gods #9 June-July 1972 (below) Forager was a Bug. Semi-human insectoids who scavenge a sorry lif from the scraps of New Genesis, home of the New Gods, the Bugs wer Kirby’s way of showing that even Utopia isn’t perfect. Such was the pow- er of the King’s ideas that characters like Bug which failed in their day have led second lives thanks to later generations of fans turned pro. His Ed Piskor is the cartoonist behind the award-winning series Hip Hop Family Tree (available from Northside). The influence of Mar- vel comics always showed in Piskor’s art, but no one knew how intense the connection between the alternative star and the House of Ideas truly was. Piskor learned how to chase down the details of rap history thanks to his life-long immersion in the complicated lore of the X-Men. -

A Study of Migration from Augusta County, Virginia, to Kentucky, 1777-1800

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1987 "Peopling the Western Country": A Study of Migration from Augusta County, Virginia, to Kentucky, 1777-1800 Wendy Sacket College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Sacket, Wendy, ""Peopling the Western Country": A Study of Migration from Augusta County, Virginia, to Kentucky, 1777-1800" (1987). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625418. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-ypv2-mw79 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "PEOPLING THE WESTERN COUNTRY": A STUDY OF MIGRATION FROM AUGUSTA COUNTY, VIRGINIA, TO KENTUCKY, 1777-1800 A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Wendy Ellen Sacket 1987 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Author Approved, December, 1987 John/Se1by *JU Thad Tate ies Whittenburg i i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.............................. iv LIST OF T A B L E S ...............................................v LIST OF MAPS . ............................................. vi ABSTRACT................................................... v i i CHAPTER I. AN INTRODUCTION TO THE LITERATURE, PURPOSE, AND ORGANIZATION OF THE PRESENT STUDY . -

Some Revolutionary War Soldiers Buried in Kentucky

Vol. 41, No. 2 Winter 2005 kentucky ancestors genealogical quarterly of the Perryville Casualty Pink Things: Some Revolutionary Database Reveals A Memoir of the War Soldiers Buried True Cost of War Edwards Family of in Kentucky Harrodsburg Vol. 41, No. 2 Winter 2005 kentucky ancestors genealogical quarterly of the Thomas E. Stephens, Editor kentucky ancestors Dan Bundy, Graphic Design Kent Whitworth, Director James E. Wallace, Assistant Director administration Betty Fugate, Membership Coordinator research and interpretation Nelson L. Dawson, Team Leader management team Kenneth H. Williams, Program Leader Doug Stern, Walter Baker, Lisbon Hardy, Michael Harreld, Lois Mateus, Dr. Thomas D. Clark, C. Michael Davenport, Ted Harris, Ann Maenza, Bud Pogue, Mike Duncan, James E. Wallace, Maj. board of Gen. Verna Fairchild, Mary Helen Miller, Ryan trustees Harris, and Raoul Cunningham Kentucky Ancestors (ISSN-0023-0103) is published quarterly by the Kentucky Historical Society and is distributed free to Society members. Periodical postage paid at Frankfort, Kentucky, and at additional mailing offices. Postmas- ter: Send address changes to Kentucky Ancestors, Kentucky Historical Society, 100 West Broadway, Frankfort, KY 40601-1931. Please direct changes of address and other notices concerning membership or mailings to the Membership De- partment, Kentucky Historical Society, 100 West Broadway, Frankfort, KY 40601-1931; telephone (502) 564-1792. Submissions and correspondence should be directed to: Tom Stephens, editor, Kentucky Ancestors, Kentucky Histori- cal Society, 100 West Broadway, Frankfort, KY 40601-1931. The Kentucky Historical Society, an agency of the Commerce Cabinet, does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, age, religion, or disability, and provides, on request, reasonable accommodations, includ- ing auxiliary aids and services necessary to afford an individual with a disability an equal opportunity to participate in all services, programs, and activities. -

Gregory, Masculinity and Homicide-Suicide 2012.Pdf

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice 40 (2012) 133e151 www.elsevier.com/locate/ijlcj Masculinity and homicide-suicide Marilyn Gregory* Department of Sociological Studies, University of Sheffield, Elmfield, Northumberland Road, Sheffield S10 2TU, UK 1. Introduction Since Ruth Cavan’s groundbreaking study of homicide followed by suicide in Chicago (Cavan, 1928), research mainly located within psychology and forensic pathology shows that homicide-suicide episodes, whilst uncommon, occur across a broad range of countries for which data have been collected. These include: Australia (Easteal, 1993; Carcach and Grabosky, 1998); England and Wales (West, 1967; Milroy, 1993; Barraclough and Harris, 2002; Flynn et al., 2009; Gregory and Milroy, 2010); Canada (Buteau et al., 1993; Gillespie et al., 1998); Finland (Kivivuori and Lehti (2003);France(Le Comte and Fornes, 1998); Hong Kong: (Beh et al., 2005); Iceland (Gudjonsson and Petursson, 1982); Israel (Landau, 1975); USA (Barber et al., 2008; Campinelli and Gilson, 2002; Hanzlick and Kopenen, 1994). Reviewing 17 studies from 10 countries, Coid (1983) found that although the rate of homicide varied widely between countries, the rate of homicide-suicide was much lessvariable.Itfollowedthatinthosecountrieswithhigher homicide rates, homicide-suicide as a percentage of homicide was smaller than in countries with lower homicide rates. Milroy (1995) reviewed the internationalliteratureagain,ana- lysing 27 studies from 17 countries and found these tendencies persisted. However, Cohen et al. (1998) found evidence to contradict this view, suggesting that homicide-suicide as apercentageoftotalhomicidesvarieswidelybetweencountries,fromaslittleas3%toas much as 60%. We know a good deal about the epidemiology of homicide-suicide from existing research (Harper and Voigt, 2007). -

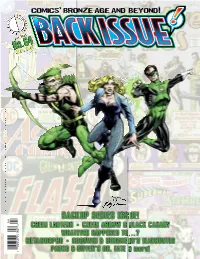

Backup Series Issue! 0 8 Green Lantern • Green Arrow & Black Canary 2 6 7 7

0 4 No.64 May 201 3 $ 8 . 9 5 1 82658 27762 8 METAMORPHO • GOODWIN & SIMONSON’S MANHUNTER GREEN LANTERN • GREEN ARROW & BLACK CANARY COMiCs PASKO & GIFFEN’S DR. FATE & more! , WHATEVER HAPPENED TO…? BACKUP SERIES ISSUE! bROnzE AGE AnD bEYOnD i . Volume 1, Number 64 May 2013 Celebrating the Best Comics of Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! the '70s, '80s, '90s, and Beyond! EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Michael Eury PUBLISHER John Morrow DESIGNER Rich Fowlks COVER ARTISTS Mike Grell and Josef Rubinstein COVER COLORIST Glenn Whitmore COVER DESIGNER Michael Kronenberg BACK SEAT DRIVER: Editorial by Michael Eury . .2 PROOFREADER Rob Smentek FLASHBACK: The Emerald Backups . .3 Green Lantern’s demotion to a Flash backup and gradual return to his own title SPECIAL THANKS Jack Abramowitz Robert Greenberger FLASHBACK: The Ballad of Ollie and Dinah . .10 Marc Andreyko Karl Heitmueller Green Arrow and Black Canary’s Bronze Age romance and adventures Roger Ash Heritage Comics Jason Bard Auctions INTERVIEW: John Calnan discusses Metamorpho in Action Comics . .22 Mike W. Barr James Kingman The Fab Freak of 1001-and-1 Changes returns! With loads of Calnan art Cary Bates Paul Levitz BEYOND CAPES: A Rose by Any Other Name … Would be Thorn . .28 Alex Boney Alan Light In the back pages of Lois Lane—of all places!—sprang the inventive Rose and the Thorn Kelly Borkert Elliot S! Maggin Rich Buckler Donna Olmstead FLASHBACK: Seven Soldiers of Victory: Lost in Time Again . .33 Cary Burkett Dennis O’Neil This Bronze Age backup serial was written during the Golden Age Mike Burkey John Ostrander John Calnan Mike Royer BEYOND CAPES: The Master Crime-File of Jason Bard . -

The Political Process in Kentucky

Kentucky Law Journal Volume 45 | Issue 3 Article 1 1957 The olitP ical Process in Kentucky Jasper Shannon University of Kentucky Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj Part of the Law and Politics Commons, and the State and Local Government Law Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits you. Recommended Citation Shannon, Jasper (1957) "The oP litical Process in Kentucky," Kentucky Law Journal: Vol. 45 : Iss. 3 , Article 1. Available at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj/vol45/iss3/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kentucky Law Journal by an authorized editor of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Political Process in Kentucky By JASPER SHANNON* CircumstancesPeculiar to Kentucky The roots of law are deeply embedded in politics. Nowhere is this more true than in Kentucky. Law frequently is the thin veneer which reason employs in a ceaseless but unsuccessful effort to control the turbulence of emotion. Born in the troubled era of the American and French Revolutions, Kentucky was in addition exposed to four years of bitter civil violence when nationalism and sectionalism struggled for supremacy (1861-65). Kentucky, ac- cordingly, within her borders has known in its most intense form the heat of passion which so often supplants reason in the clash of interests forming the heart of legal and political processes. Too many times in its colorful history the forms of law have broken down in the conflict of emotions. -

A Native History of Kentucky

A Native History Of Kentucky by A. Gwynn Henderson and David Pollack Selections from Chapter 17: Kentucky in Native America: A State-by-State Historical Encyclopedia edited by Daniel S. Murphree Volume 1, pages 393-440 Greenwood Press, Santa Barbara, CA. 2012 1 HISTORICAL OVERVIEW As currently understood, American Indian history in Kentucky is over eleven thousand years long. Events that took place before recorded history are lost to time. With the advent of recorded history, some events played out on an international stage, as in the mid-1700s during the war between the French and English for control of the Ohio Valley region. Others took place on a national stage, as during the Removal years of the early 1800s, or during the events surrounding the looting and grave desecration at Slack Farm in Union County in the late 1980s. Over these millennia, a variety of American Indian groups have contributed their stories to Kentucky’s historical narrative. Some names are familiar ones; others are not. Some groups have deep historical roots in the state; others are relative newcomers. All have contributed and are contributing to Kentucky's American Indian history. The bulk of Kentucky’s American Indian history is written within the Commonwealth’s rich archaeological record: thousands of camps, villages, and town sites; caves and rockshelters; and earthen and stone mounds and geometric earthworks. After the mid-eighteenth century arrival of Europeans in the state, part of Kentucky’s American Indian history can be found in the newcomers’ journals, diaries, letters, and maps, although the native voices are more difficult to hear. -

Homestead Heroism in Appalachian Fiction

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 5-2005 Angel on the Mountain: Homestead Heroism in Appalachian Fiction Nicole Marie Drewitz-Crockett University of Tennessee, Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Drewitz-Crockett, Nicole Marie, "Angel on the Mountain: Homestead Heroism in Appalachian Fiction. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2005. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/4564 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Nicole Marie Drewitz-Crockett entitled "Angel on the Mountain: Homestead Heroism in Appalachian Fiction." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in English. Allison Ensor, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Thomas Haddox, Dawn Coleman Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Nicole Marie Drewitz-Crockett entitled "Angel on the Mountain: Homestead Heroism in Appalachian Fiction." I have examined the final paper copy of this thesis forform and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in English. -

The JACK KIRBY COLLECTOR #69

1 82658 00098 1 The JACK KIRBY COLLECTOR FALL 2016 FALL $10.95 #69 All characters TM & © Simon & Kirby Estates. THE Contents PARTNERS! OPENING SHOT . .2 (watch the company you keep) FOUNDATIONS . .3 (Mr. Scarlet, frankly) ISSUE #69, FALL 2016 C o l l e c t o r START-UPS . .10 (who was Jack’s first partner?) 2016 EISNER AWARDS NOMINEE: BEST COMICS-RELATED PERIODICAL PROSPEAK . .12 (Steve Sherman, Mike Royer, Joe Sinnott, & Lisa Kirby discuss Jack) KIRBY KINETICS . .18 (Kirby + Wood = Evolution) FANSPEAK . .22 (a select group of Kirby fans parse the Marvel settlement) JACK KIRBY MUSEUM PAGE . .29 (visit & join www.kirbymuseum.org) KIRBY OBSCURA . .30 (Kirby sees all!) CLASSICS . .32 (a Timely pair of editors are interviewed) RE-PAIRINGS . .36 (Marvel-ous cover recreations) GALLERY . .39 (some Kirby odd couplings) INPRINT . .49 (packaging Jack) INNERVIEW . .52 (Jack & Roz—partners for life) INCIDENTAL ICONOGRAPHY . .60 (Sandman & Sandy revamped) OPTIKS . .62 (Jack in 3-D Land) SCULPTED . .72 (the Glenn Kolleda incident) JACK F.A.Q.s . .74 (Mark Evanier moderates the 2016 Comic-Con Tribute Panel, with Kevin Eastman, Ray Wyman Jr., Scott Dunbier, and Paul Levine) COLLECTOR COMMENTS . .92 (as a former jazz bass player, the editor of this mag was blown away by the Sonny Rollins letter...) PARTING SHOT . .94 (never trust a dwarf with a cannon) Cover inks: JOE SINNOTT from Kirby Unleashed Cover color: TOM ZIUKO If you’re viewing a Digital Edition of this publication, PLEASE READ THIS: This is copyrighted material, NOT intended Direct from Roz Kirby’s sketchbook, here’s a team of partners that holds a for downloading anywhere except our website or Apps. -

Comics Collected Editions Original Graphic Novels

Store info: FILL OUT THIS INTERACTIVE CHECKLIST AND RETURN TO YOUR RETAILER TO MAKE SURE YOU DON’T MISS THE LATEST FROM DC! (Tuesday availability at participating stores) TO VIEW CATALOG, VISIT: DCCOMICS.COM/CONNECT COMICS _ _ Detective Comics #1038 _ _ Event Leviathan: Checkmate #1 M V M = Main V = Variant _ _ Harley Quinn #4 Check with your retailer for variant cover details. _ _ Infinite Frontier #1 Available Tuesday, April 20, 2021 _ _ Mister Miracle: The Source of Freedom #2 _ _ Robin #3 _ _ Batman/Fortnite: Zero Point #1 _ _ RWBY/Justice League #3 Available Tuesday, May 4, 2021 _ _ Teen Titans Academy #4 _ _ Batman/Fortnite: Zero Point #2 _ _ Wonder Woman #774 _ _ Wonder Woman Black & Gold #1 RAPHIC Available Tuesday, May 18, 2021 _ _ Batman/Fortnite: Zero Point #3 Available Tuesday, June 29, 2021 _ _ Action Comics 2021 Annual #1 Available Tuesday, June 1, 2021 _ _ Catwoman 2021 Annual #1 _ _ Batman #109 _ _ The Flash 2021 Annual #1 _ _ Batman/Fortnite: Zero Point #4 _ _ Green Arrow 80th Anniversary 100-Page Super Spectacular _ _ Batman: The Adventures Continue II #1 _ _ Infinite Frontier: Secret Files #1 _ _ Crime Syndicate #4 _ _ Space Jam: A New Legacy _ _ Crush & Lobo #1 _ _ Teen Titans Academy 2021 Yearbook #1 _ _ Far Sector #12 _ _ Green Lantern #3 Available Tuesday, July 6, 2021 _ _ Justice League #62 _ _ Batman/Fortnite: Zero Point #6 _ _ Man-Bat #5 _ _ Sensational Wonder Woman #4 COLLECTED EDITIONS _ _ Suicide Squad #4 _ _ The Dreaming: Waking Hours #11 Available Tuesday, July 6, 2021 _ _ The Next Batman: Second Son #3 _