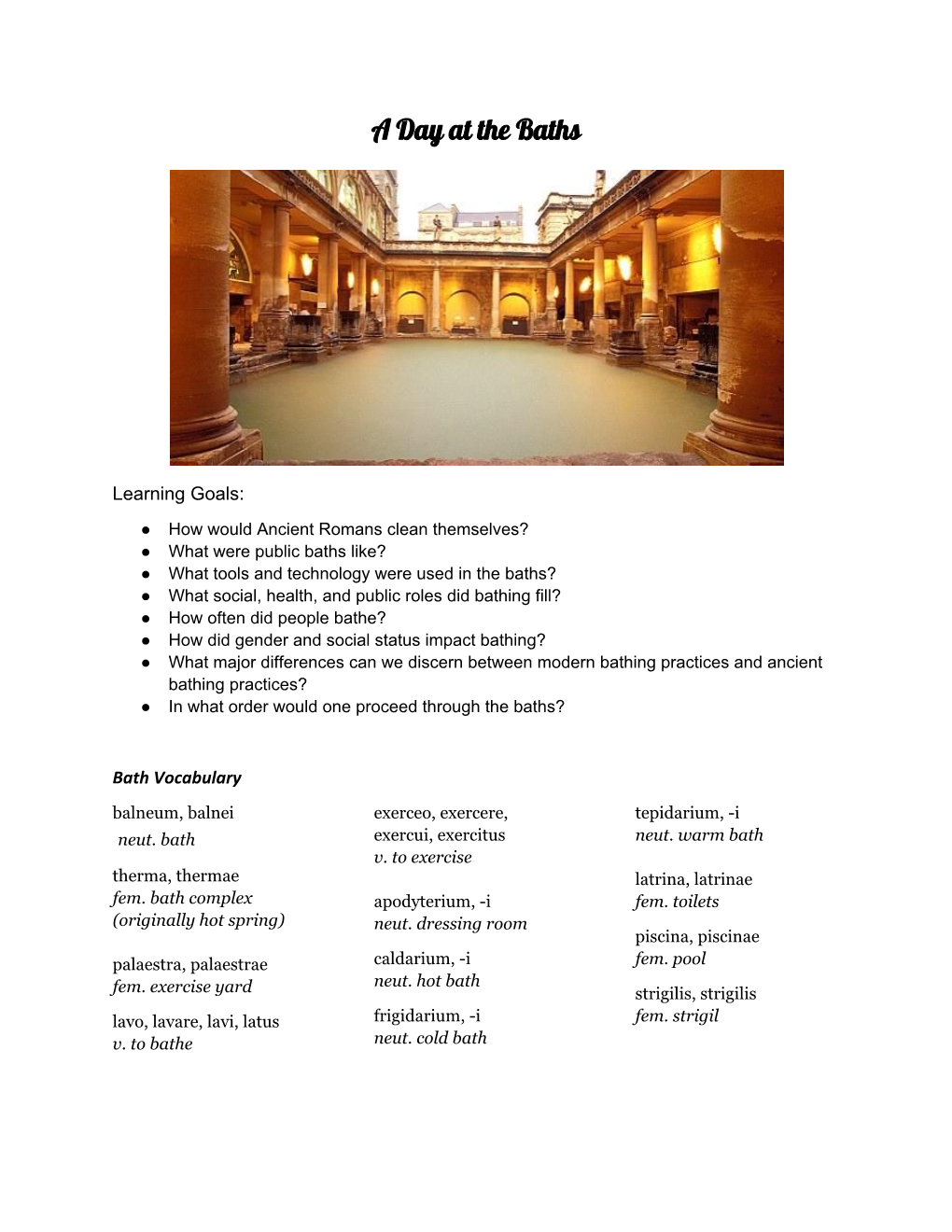

A Day at the Baths

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reconstructing the Baths of Caracalla

Digital Applications in Archaeology and Cultural Heritage 1 (2014) 45–54 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Digital Applications in Archaeology and Cultural Heritage journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/daach Reconstructing the Baths of Caracalla Taylor Oetelaar Department of Mechanical and Manufacturing Engineering, University of Calgary, 2500 University Drive, NW Calgary, AB, Canada T2N 1N4 article info abstract Article history: The Baths of Caracalla are the second largest but most complete bathing complex in the city of Rome. Received 20 May 2013 They are a representation of the might, wealth, and ingenuity of the Roman Empire. As such, a brief Received in revised form introduction to the site of the Baths of Caracalla and its layout is advantageous. This article chronicles the 5 October 2013 digital reconstruction process that began as a means to obtain the geometry of one room for the purposes Accepted 9 December 2013 of a thermal analysis. Unlike many reconstructions, this one uses a parametric design program, Available online 21 December 2013 SolidWorks, as the base because it allows for easy and precise manipulation of the geometry. While this recreation still has rough textures, it provides insights into the geometry: particularly surrounding the glass in the windows. The 3D model allows the viewer to partially experience the atmosphere of the site and illustrates its enormity. & 2014 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. 1. Introduction not fully capture the opulence of the Baths, it is a 3D scale model that can provide scholars measurements not available with comparative The Baths of Caracalla in Rome, Italy were the second largest models. -

Logistics of Building Processes: the Stabian Baths in Pompeii

Logistics of Building Processes: The Stabian Baths in Pompeii Monika Trümper When Pompeii was buried by Vesuvius in 79 AD, the city boasted three large baths and a series of smaller establishments. The construction of these baths required significant efforts, in terms of logistics, building material and technological skills, especially with regard to the necessary water management, heating system and vaulting. While building processes and construction techniques have received significant attention in scholarship on Pompeii1, these have not yet been discussed specifically for Pompeian baths. This paper attempts to fill this gap, focusing on the Stabian Baths that were longest used of all Pompeian establishments. They are also the target of a new research project that is being carried out within the frame of the Excellence Cluster Topoi in Berlin and investigates the development, function, and socio-cultural context of the Stabian and Republican Baths.2 Following a brief overview of the state of research, this paper will discuss preliminary results of the new project. In his monograph from 1979, Hans Eschebach proposed a development of the Stabian Baths in six phases from the 5th century BC to the Imperial period (fig. 1).3 Eschebach’s phase VI includes all of the many building measures carried out in the Imperial period. He did not discuss building logistics and reconstructed phases, which would have entailed numerous major constructional changes. For example, the porticoes of the palaestra (fig. 2: B/C), including the styblobates, drainage channels, columns, and roofs would have been modified and moved repeatedly: the eastern portico four times and the southern and northern porticoes at least twice. -

An Innovative Investigation of the Thermal Environment Inside the Reconstructed Caldaria of Two Ancient Roman Baths Using Computational Fluid Dynamics

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2013-01-18 An Innovative Investigation of the Thermal Environment inside the Reconstructed Caldaria of Two Ancient Roman Baths Using Computational Fluid Dynamics Oetelaar, Taylor Oetelaar, T. (2013). An Innovative Investigation of the Thermal Environment inside the Reconstructed Caldaria of Two Ancient Roman Baths Using Computational Fluid Dynamics (Unpublished doctoral thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/24900 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/435 doctoral thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY An Innovative Investigation of the Thermal Environment inside the Reconstructed Caldaria of Two Ancient Roman Baths Using Computational Fluid Dynamics by Taylor Anthony Oetelaar A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF MECHANICAL AND MANUFACTURING ENGINEERING CALGARY, ALBERTA JANUARY, 2013 © Taylor Anthony Oetelaar 2013 Abstract The overarching premise of this dissertation is to use engineering principles and classical archaeological data to create knowledge that benefits both disciplines: transdisciplinary research. Specifically, this project uses computational fluid dynamics (CFD) to analyze the thermal environment inside one room of two Roman bath buildings. By doing so, this research reveals the temperature distribution and velocity profiles inside the room of interest. -

Manolis Manoledakis

SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES Healing Gods: The Cult of Apollo Iatros, Asclepius and Hygieia in the Black Sea Region Moschakis Konstantinos A Dissertation thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Master of Arts (MA) in Black Sea Cultural Studies Supervisor: Manolis Manoledakis September 2013 Thessaloniki – Greece I hereby declare that the work submitted by me is mine and that where I have made use of another’s work, I have attributed the source(s) according to the Regulations set in the Student’s Handbook. September 2013 Thessaloniki – Greece Healing Gods: The Cult of Apollo Iatros, Asclepius and Hygieia in the Black Sea Region To my parents, Δημήτρη and Αλεξάνδρα. « πᾶς δ' ὀδυνηρὸς βίος ἀνθρώπων κοὐκ ἔστι πόνων ἀνάπαυσις» «The life of man entire is misery he finds no resting place, no haven of calamity» Euripides, Hippolytos (189-190) (transl. D. Greene) TABLE OF CONTENTS Contents……………………………………………………………………………01 Sources- Abbreviations- Bibliography…………………………………………...03 Preface……………………………………………………………………………...17 Introduction………………………………………………………………………..19 PART A 1. The Cult of Apollo Iatros in the North and Western Black Sea: Epigraphic Evidence and Archaeological Finds. 1.01. Olbia-Berezan………………………………………………………………22 1.02. Panticapaeum (Kerch)………………………………………………………25 1.03. Hermonassa…………………………………………………………………26 1.04. Myrmekion………………………………………………………………….27 1.05. Phanagoria…………………………………………………………………..27 1.06. Apollonia Pontica……………………………………………………….......27 1.07. Istros (Histria)………………………………………………………………29 1.08. Tyras…………………………………………………………………….......30 PART B 1. The Cult of Asclepius and Hygieia in the Northern Black Sea Region: Epigraphic Evidence and Archaeological Finds. 1.01. The cities in the Northern Black Sea…………………………………………..31 1.02. Chersonesus……………………………………………………………………31 1.03. Olbia…………………………………………………………………………...34 1.04. Panticapaeum (Kerch)…………………………………………………………35 2. The Cult of Asclepius and Hygeia in the Southern Black Sea Region: Epigraphic Evidence and Archaeological Finds. -

Development of Gymnasia and Graeco- Roman Cityscapes

58 Development of Gymnasia and Graeco- Roman Cityscapes Ulrich Mania Monika Trümper (eds.) BERLIN STUDIES OF THE ANCIENT WORLD was one of the key monuments for the formation of urban space and identity in Greek culture, and its transformation was closely interlinked with changing concepts of cityscaping. Knowledge as well as transfer of knowledge, ideas and concepts were crucial for the spread and long-lasting importance of gymnasia within and beyond the Greek and Roman world. The contributions investigate the relationship between gymnasia and cityscapes in the Hellenistic and Roman Imperial period as well as in the eastern and western Mediterranean, revealing chronological (dis)conti- nuities and geographical (dis)similarities. The focus in the much-neglected west is on Sicily and South Italy (Akrai, Cuma, Herculaneum, Megara Hyblaea, Morgantina, Neaiton, Pompeii, Segesta, Syracuse), while many major sites with gymnasia from the entire eastern Mediterranean are included (Athens, Eretria, Olympia, Pergamon, Rhodes). Central topics comprise the critical reevaluation of specifi c sites and building types, the discussion of recent fi eldwork, the assessment of sculptural decora- tion, and new insights about the gymnasiarchy and ruler cult in gymnasia. berlin studies of 58 the ancient world berlin studies of the ancient world · 58 edited by topoi excellence cluster Development of Gymnasia and Graeco-Roman Cityscapes edited by Ulrich Mania and Monika Trümper Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliographie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de. © 2018 Edition Topoi / Exzellenzcluster Topoi der Freien Universität Berlin und der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin Cover image: Doryphoros (Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli, inv. -

Roman Woman, Culture, and Law Heather Faith Wright Western Oregon University

Western Oregon University Digital Commons@WOU Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History) Department of History 2010 Roman Woman, Culture, and Law Heather Faith Wright Western Oregon University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/his Part of the Cultural History Commons, European History Commons, and the Women's History Commons Recommended Citation Wright, Heather Faith, "Roman Woman, Culture, and Law" (2010). Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History). 79. https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/his/79 This Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at Digital Commons@WOU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History) by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@WOU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Roman Woman, Culture, and Law By Heather Faith Wright Senior Seminar: HST 499 Professor John L. Rector Western Oregon University June 5, 2010 Readers Professor Benedict Lowe Professor Laurie Carlson Copyright @ Heather Wright, 2010 2 The topic of my senior thesis is Women of the Baths. Women were an important part of the activities and culture that took place within the baths. Throughout Roman history bathing was important to the Romans. By the age of Augustus visiting the baths had become one of the three main activities in a Roman citizen’s daily life. The baths were built following the current trends in architecture and were very much a part of the culture of their day. The architecture, patrons, and prostitutes of the Roman baths greatly influenced the culture of this institution. The public baths of both the Roman Republic and the Roman Empire were important social environment to hear or read poetry and meet lovers. -

Download This PDF File

КУЛТУРНОТО НАСЛЕДСТВО НА ВАРНА И ЧЕРНОМОРСКИЯ РЕГИОН DIGITIZATION OF OBJECTS OF CULTURAL HERITAGE OF VARNA, PRODUCED IN THE STUDIO ARCHITECTURAL SPIES IN THE PERIOD 2013-2019 Nadya Stamatova Abstract: This publication focuses on creating a database of 3D models for an augmented reality mobile application allowing the visualization of the past condition of cultural heritage buildings in the real environment of the city of Varna, some of them no longer present in cityscape. Keywords: digitization, digitalization, archaeology, 3D models, heritage, cultural heritage, photogrammetry, augmented reality, virtual reality, 3D, AR,VR, MR,MAR,XR,CH This publication presents the results of an issue of the National Center for Digitization training young professionals and students to obtain of the Balkans, Black Sea Region and Caucasus practical skills in digitization of the cultural and [1, 2, 3], as well the 3D models of two statues of historical heritage. The paper presents the result Nike [4, 5] and one of Heracles [6]. of the seven-year period from 2013 to 2019 of the The first of the three publications mentioned digitization work in the R&D SME Architectural above reveals to the general public the difficult Spies and the architectural studio Architectural start of digitizing in the studio Architectural Spies Space under the mentorship of the architect objects of the cultural heritage. This has a close Dr. Nadya Stamatova of young architects and connection with the work of Dr. N. Stamatova engineers on the international programs Erasmus, on the digital reconstruction of the Imperial Ro- Leonardo da Vinci, Cornelius Hertling, Erasmus+, man Thermae of the ancient Odessos according to and the national program Students’ Internships the sketches and the hand drawings, provided by of the Ministry of the Science and Education of Prof. -

Roman Building Materials, Construction Methods, and Architecture: the Dei Ntity of an Empire Michael Strickland Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 8-2010 Roman Building Materials, Construction Methods, and Architecture: The deI ntity of an Empire Michael Strickland Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Strickland, Michael, "Roman Building Materials, Construction Methods, and Architecture: The deI ntity of an Empire" (2010). All Theses. 909. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/909 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ROMAN BUILDING MATERIALS, CONSTRUCTION METHODS, AND ARCHITECTURE: THE IDENTITY OF AN EMPIRE A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts History by Michael Harold Strickland August 2010 Accepted by: Dr. Pamela Mack, Committee Chair Dr. Alan Grubb Dr. Caroline Dunn i ABSTRACT Empires have been identified in various ways such as by the land area under their control, by their duration, their level of economic influence, or military might. The Roman Empire was not the world’s largest and its duration, although notable, was not extraordinary. Military power was necessary for conquering the area brought under the control of the Empire. However, for the Romans, the ability and capacity for construction is what identified and expressed the Empire when it began and identifies the Empire today. The materials used, construction techniques employed, and architectural styles for structures for government, entertainment, dwellings, bridges, and aqueducts will be discussed. -

The Athletic Aesthetic in Rome's Imperial Baths

Heather L. Reid The Athletic Aesthetic in Rome’s Imperial Baths Abstract The Greek gymnasium was replicated in the architecture, art, and activities of the Imperial Roman thermae. This mimēsis was rooted in sincere admiration of traditional Greek paideia – especially the glory of Athens’ Academy and Lyceum – but it did not manage to replicate the gymnasium’s educational impact. This article reconstructs the aesthetics of a visit to the Roman baths, explaining how they evoked a glorious Hellenic past, offering the opportunity to Romans to imagine being «Greek». But true Hellenic paideia was always kept at arm’s len- gth by an assumption of Roman cultural superiority. One may play at being a Greek athlete or philosopher, but one would never dedicate one’s life to it. The experience of the Imperial thermae celebrated Greek athletic culture, but it remained too superficial – toospectatorial – to effect the change of soul demanded by classical gymnastic education. Keywords: Roman Baths, Greek Gymnasium, Paideia, Ancient Athletics, Vitruvius. Imperial Rome inherited not only the art and architecture of the classical Greek gymnasium, but also its philosophy. And just as the Romans creatively merged the architectural features of the Greek palaestra into their baths, so they adapted the art, activities, and ideas of the gymnasium to suit their own tastes and purpo- ses. The distinction between Greeks and Romans here is neither ethnic nor po- litical; by this time most ethnic Greeks were Romans and their culture had been absorbed – even embraced – under the Empire. The distinction is rather between the Roman subject of the Empire, whatever his or her language and background, and the idealized Heroic and Classical culture of what was – even for Imperial Romans – ancient Greece. -

Variation in Representation Through Architectural Benefaction Under Roman Rule: Five Cases from the Province of Asia C

Durham E-Theses Variation in Representation through Architectural Benefaction under Roman Rule: Five Cases from the Province of Asia c. 40 B.C. A.D. 68 TOMAS, JULIA,MARGARET How to cite: TOMAS, JULIA,MARGARET (2020) Variation in Representation through Architectural Benefaction under Roman Rule: Five Cases from the Province of Asia c. 40 B.C. A.D. 68, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/13518/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 1 Variation in Representation through Architectural Benefaction under Roman Rule: Five Cases from the Province of Asia c. 40 B.C. – A.D. 68. Abstract This thesis explores a new approach to understanding the influence that Rome had on its provinces through a study of architectural benefactors and their buildings. It moves away from the process-centric approach which has been prevalent in scholarship since the mid nineteenth century. -

| 3 Roman Baths: an Alternate Mode of Viewing the Evidence

Roman Baths: An Alternate Mode of Viewing the Evidence Tanya Henderson, University of Alberta Roman baths are an important component in furthering our knowl- edge of Roman social life. They functioned as more than just a locus for cleansing the body. Currently, the literary sources provide the | 3 most details about the various social activities that occurred in the baths. However, where these activities took place within the com- plexes remains unclear. Archaeological reports do not adequately address how the rooms functioned. The argument presented here outlines some of the problems with the current methodology for ex- amining room function in room baths. Then, using the site of Ham- mat Gader in Israel, introduces a different mode of viewing the evi- dence. The activities that occurred in Roman baths are significant in under- standing Roman social life. The baths were the setting for more than just cleansing the body and a variety of ball games, wrestling, eating and other social activities took place within the baths.1 Literary sources, such as Pliny the Younger, Martial and Juvenal, all provide us with accounts of life at the baths.2 Yet, while there is an abun- 1 For ball games see: Petronius, Sat., 27; Mart., Epig. 14.47 and 7.32. For wrestling see Juv., 6.422-423. For eating see Sen., Ep. 56.2. 2 For a complete list of literary sources that mention the baths and to realize the sheer volume of literary evidence see I. Nielsen, Thermae et Balnea (Aarhus, Den- Past Imperfect 13 (2007) | © | ISSN 1192-1315 dance of literary evidence that provides a general idea as to what these activities were, it is still unclear as to where these activities took place within the bath complex. -

Baths of Caracalla

The Baths of Caracalla Imagine an October storm in the hills over Rome. The sky darkens. The birds fall silent. A cold wind stirs the aspens. A few tentative raindrops patter on the trees; and then, with a sigh, a steady shower starts to fall. Golden leaves shimmer; gray boulders glisten; and slender streams begin to ribbon their way down the rocky slope. A brook catches the water and whirls it down the mountainside. The current roars against boulders and surges over waterfalls – and then, suddenly, joins a placid pool in a remote valley. Foam drifts gently across the surface as a gurgling drain becomes audible. Floating leaves and twigs catch on an iron screen; but the water plummets into a dark tunnel. And there, for sixty miles, it remains, joining the fifty million gallons of water that flow daily down the concrete channel of the Marcian Aqueduct. A few miles from Rome, above a road lined with proud marble tombs, a channel opens on the left. Hundreds of thousands of gallons follow this branch over the Via Appia, down a mile-long tunnel, and into the stillness of a two-million gallon reservoir. Over the following day, the water is drawn through a series of chambers with heated floors and walls. At last, warmed almost to boiling, it funnels down insulated lead pipes, snakes through complicated plumbing, and streams into the marble basin of a fountain. A gilded ceiling, half-hidden by steam, shimmers 150 feet overhead; and glass mosaics twinkle on the walls as the water cascades into the seven heated pools of the Baths of Caracalla.