Baths of Caracalla

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study of the Pantheon Through Time Caitlin Williams

Union College Union | Digital Works Honors Theses Student Work 6-2018 A Study of the Pantheon Through Time Caitlin Williams Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, and the Classical Archaeology and Art History Commons Recommended Citation Williams, Caitlin, "A Study of the Pantheon Through Time" (2018). Honors Theses. 1689. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/1689 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Union | Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Union | Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Study of the Pantheon Through Time By Caitlin Williams * * * * * * * Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Department of Classics UNION COLLEGE June, 2018 ABSTRACT WILLIAMS, CAITLIN A Study of the Pantheon Through Time. Department of Classics, June, 2018. ADVISOR: Hans-Friedrich Mueller. I analyze the Pantheon, one of the most well-preserVed buildings from antiquity, through time. I start with Agrippa's Pantheon, the original Pantheon that is no longer standing, which was built in 27 or 25 BC. What did it look like originally under Augustus? Why was it built? We then shift to the Pantheon that stands today, Hadrian-Trajan's Pantheon, which was completed around AD 125-128, and represents an example of an architectural reVolution. Was it eVen a temple? We also look at the Pantheon's conversion to a church, which helps explain why it is so well preserVed. -

Spoliation in Medieval Rome Dale Kinney Bryn Mawr College, [email protected]

Bryn Mawr College Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College History of Art Faculty Research and Scholarship History of Art 2013 Spoliation in Medieval Rome Dale Kinney Bryn Mawr College, [email protected] Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.brynmawr.edu/hart_pubs Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons Custom Citation Kinney, Dale. "Spoliation in Medieval Rome." In Perspektiven der Spolienforschung: Spoliierung und Transposition. Ed. Stefan Altekamp, Carmen Marcks-Jacobs, and Peter Seiler. Boston: De Gruyter, 2013. 261-286. This paper is posted at Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College. http://repository.brynmawr.edu/hart_pubs/70 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Topoi Perspektiven der Spolienforschung 1 Berlin Studies of the Ancient World Spoliierung und Transposition Edited by Excellence Cluster Topoi Volume 15 Herausgegeben von Stefan Altekamp Carmen Marcks-Jacobs Peter Seiler De Gruyter De Gruyter Dale Kinney Spoliation in Medieval Rome i% The study of spoliation, as opposed to spolia, is quite recent. Spoliation marks an endpoint, the termination of a buildlng's original form and purpose, whÿe archaeologists tradition- ally have been concerned with origins and with the reconstruction of ancient buildings in their pristine state. Afterlife was not of interest. Richard Krautheimer's pioneering chapters L.,,,, on the "inheritance" of ancient Rome in the middle ages are illustrated by nineteenth-cen- tury photographs, modem maps, and drawings from the late fifteenth through seventeenth centuries, all of which show spoliation as afalt accomplU Had he written the same work just a generation later, he might have included the brilliant graphics of Studio Inklink, which visualize spoliation not as a past event of indeterminate duration, but as a process with its own history and clearly delineated stages (Fig. -

Spolia from the Baths of Caracalla in Sta. Maria in Trastevere Dale Kinney Bryn Mawr College, [email protected]

Bryn Mawr College Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College History of Art Faculty Research and Scholarship History of Art 1986 Spolia from the Baths of Caracalla in Sta. Maria in Trastevere Dale Kinney Bryn Mawr College, [email protected] Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.brynmawr.edu/hart_pubs Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Custom Citation Kinney, Dale. 1986. " Spolia from the Baths of Caracalla in Sta. Maria in Trastevere." The Art Bulletin 68.3: 379-397. This paper is posted at Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College. https://repository.brynmawr.edu/hart_pubs/90 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Spolia from the Baths of Caracallain Sta. Maria in Trastevere Dale Kinney Eight third-century Ionic capitals with images of Isis, Serapis, and Harpocrates, now in the nave colonnades of Sta. Maria in Trastevere, were taken from one or both of the rooms currently identified as libraries in the Baths of Caracalla. The capitals were transferred around 1140, when the church was rebuilt by Pope In- nocent II. The capitals would have been acquired by confiscation, juridically the pope's prerogative as head of the papal state; the lavish display of all kinds of spolia in Sta. Maria in Trastevere is here interpreted as a self-conscious demon- stration of that prerogative. The identity of the capitals' pagan images would have been unknown to most twelfth-century observers, because the only accessible keys to the correct identifications were one sentence in Varro's De lingua latina and another in Saint Augustine's De civitate Dei. -

Reconstructing the Baths of Caracalla

Digital Applications in Archaeology and Cultural Heritage 1 (2014) 45–54 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Digital Applications in Archaeology and Cultural Heritage journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/daach Reconstructing the Baths of Caracalla Taylor Oetelaar Department of Mechanical and Manufacturing Engineering, University of Calgary, 2500 University Drive, NW Calgary, AB, Canada T2N 1N4 article info abstract Article history: The Baths of Caracalla are the second largest but most complete bathing complex in the city of Rome. Received 20 May 2013 They are a representation of the might, wealth, and ingenuity of the Roman Empire. As such, a brief Received in revised form introduction to the site of the Baths of Caracalla and its layout is advantageous. This article chronicles the 5 October 2013 digital reconstruction process that began as a means to obtain the geometry of one room for the purposes Accepted 9 December 2013 of a thermal analysis. Unlike many reconstructions, this one uses a parametric design program, Available online 21 December 2013 SolidWorks, as the base because it allows for easy and precise manipulation of the geometry. While this recreation still has rough textures, it provides insights into the geometry: particularly surrounding the glass in the windows. The 3D model allows the viewer to partially experience the atmosphere of the site and illustrates its enormity. & 2014 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. 1. Introduction not fully capture the opulence of the Baths, it is a 3D scale model that can provide scholars measurements not available with comparative The Baths of Caracalla in Rome, Italy were the second largest models. -

Logistics of Building Processes: the Stabian Baths in Pompeii

Logistics of Building Processes: The Stabian Baths in Pompeii Monika Trümper When Pompeii was buried by Vesuvius in 79 AD, the city boasted three large baths and a series of smaller establishments. The construction of these baths required significant efforts, in terms of logistics, building material and technological skills, especially with regard to the necessary water management, heating system and vaulting. While building processes and construction techniques have received significant attention in scholarship on Pompeii1, these have not yet been discussed specifically for Pompeian baths. This paper attempts to fill this gap, focusing on the Stabian Baths that were longest used of all Pompeian establishments. They are also the target of a new research project that is being carried out within the frame of the Excellence Cluster Topoi in Berlin and investigates the development, function, and socio-cultural context of the Stabian and Republican Baths.2 Following a brief overview of the state of research, this paper will discuss preliminary results of the new project. In his monograph from 1979, Hans Eschebach proposed a development of the Stabian Baths in six phases from the 5th century BC to the Imperial period (fig. 1).3 Eschebach’s phase VI includes all of the many building measures carried out in the Imperial period. He did not discuss building logistics and reconstructed phases, which would have entailed numerous major constructional changes. For example, the porticoes of the palaestra (fig. 2: B/C), including the styblobates, drainage channels, columns, and roofs would have been modified and moved repeatedly: the eastern portico four times and the southern and northern porticoes at least twice. -

An Exclusive Concert Series for Orchestras

American Celebration of Music in Italy presents the An exclusive concert series for orchestras Crescendo to Cremona Series Music Celebrations International is pleased to present the Crescendo to Cremona Series as part of the American Celebration of Music in Italy! Melded from Greek, Etruscan and Roman civilizations, Italian culture has influenced Western thought, art, music, literature and civilization more than any other. As you travel from Rome to the finale in Cremona, the senses will almost reel from exposure to history, architecture, art, and beauty unequaled anywhere else in Europe. Known around the world for its tradition of stringed instrument produc- tion, Cremona has been a famous music center since the 16th-century and still prides itself for its artisan workshops producing high-quality stringed instruments. Cremona’s finest resident luthier was Antonio Stradivari. It is estimated Stradivari produced over 1,000 instruments, of which only 650 survive today and are still some of the finest in the world. A concert and experience in Italy is a return to the roots of Western Civili- zation. Regardless of one’s musical tastes - classical, church, ballad, opera, chant, symphonic, Romanesque, Gothic, Renaissance, Romantic, Baroque - these roots are all found in Italy. Our musical heritage certainly was born in Italy. Italians, with help from the French, invented the system of mu- sical notation used today. Cremona produced violins by Stradivarius and Guarneri; the piano is an Italian invention. Italian composers like Verdi, Gabrieli, Monteverdi, Paganini, Vivaldi, Puccini and Rossini are household names. Select orchestras are invited to share their talents with appreciative audiences in glorious venues and spectacular settings throughout Italy as part of this unique concert series. -

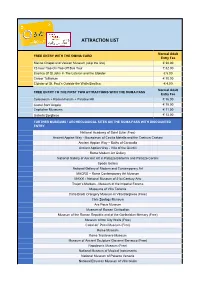

Attraction List

ATTRACTION LIST Normal Adult FREE ENTRY WITH THE OMNIA CARD Entry Fee Sistine Chapel and Vatican Museum (skip the line) € 30.00 72-hour Hop-On Hop-Off Bus Tour € 32.00 Basilica Of St.John In The Lateran and the Cloister € 5.00 Carcer Tullianum € 10.00 Cloister of St. Paul’s Outside the Walls Basilica € 4.00 Normal Adult FREE ENTRY TO THE FIRST TWO ATTRACTIONS WITH THE ROMA PASS Entry Fee Colosseum + Roman Forum + Palatine Hill € 16.00 Castel Sant’Angelo € 15.00 Capitoline Museums € 11.50 Galleria Borghese € 13.00 FURTHER MUSEUMS / ARCHEOLOGICAL SITES ON THE ROMA PASS WITH DISCOUNTED ENTRY National Academy of Saint Luke (Free) Ancient Appian Way - Mausoleum of Cecilia Metella and the Castrum Caetani Ancient Appian Way – Baths of Caracalla Ancient Appian Way - Villa of the Quintili Rome Modern Art Gallery National Gallery of Ancient Art in Palazzo Barberini and Palazzo Corsini Spada Gallery National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art MACRO – Rome Contemporary Art Museum MAXXI - National Museum of 21st Century Arts Trajan’s Markets - Museum of the Imperial Forums Museums of Villa Torlonia Carlo Bilotti Orangery Museum in Villa Borghese (Free) Civic Zoology Museum Ara Pacis Museum Museum of Roman Civilization Museum of the Roman Republic and of the Garibaldian Memory (Free) Museum of the City Walls (Free) Casal de’ Pazzi Museum (Free) Rome Museum Rome Trastevere Museum Museum of Ancient Sculpture Giovanni Barracco (Free) Napoleonic Museum (Free) National Museum of Musical Instruments National Museum of Palazzo Venezia National Etruscan -

Waters of Rome Journal

THE CLOACA MAXIMA AND THE MONUMENTAL MANIPULATION OF WATER IN ARCHAIC ROME John N. N. Hopkins [email protected] Introduction cholars generally conceive of the Cloaca Maxima as a Smassive drain flushing away Rome’s unappealing waste. This is primarily due to the historiographic popularity of Imperial Rome, when the Cloaca was, in fact, a sewer. By the time Frontinus assumed the post of curator aquarum in 97 AD, its concrete and masonry tunnels channeled Rome’s refuse beneath the Fora and around the hills, and stood among extensive drainage networks in the valleys of the Circus Maximus, Campus Martius and Transtiberim (Figs. 1 & 2).1 Built on seven hundred years of evolving hydraulic engineering and architecture, it was acclaimed in the first century as a work “for which the new magnificence of these days has scarcely been able to produce a match.”2 The Cloaca did not, however, always serve the city in this manner. Archaeological and literary evidence suggests that in the sixth century BC, the last three kings of Rome produced a structure that was entirely different from the one historians knew under the Empire. What is more, evidence suggests these kings built it to serve entirely different purposes. The Cloaca began as a monumental, open-air, fresh-water canal (Figs. 3 & 4). This canal guided streams through the newly leveled, paved, open space that would become the Forum Romanum. In this article, I reassess this earliest phase of the Cloaca Maxima when it served a vital role in changing the physical space of central Rome and came to signify the power of the Romans who built it. -

An Innovative Investigation of the Thermal Environment Inside the Reconstructed Caldaria of Two Ancient Roman Baths Using Computational Fluid Dynamics

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2013-01-18 An Innovative Investigation of the Thermal Environment inside the Reconstructed Caldaria of Two Ancient Roman Baths Using Computational Fluid Dynamics Oetelaar, Taylor Oetelaar, T. (2013). An Innovative Investigation of the Thermal Environment inside the Reconstructed Caldaria of Two Ancient Roman Baths Using Computational Fluid Dynamics (Unpublished doctoral thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/24900 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/435 doctoral thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY An Innovative Investigation of the Thermal Environment inside the Reconstructed Caldaria of Two Ancient Roman Baths Using Computational Fluid Dynamics by Taylor Anthony Oetelaar A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF MECHANICAL AND MANUFACTURING ENGINEERING CALGARY, ALBERTA JANUARY, 2013 © Taylor Anthony Oetelaar 2013 Abstract The overarching premise of this dissertation is to use engineering principles and classical archaeological data to create knowledge that benefits both disciplines: transdisciplinary research. Specifically, this project uses computational fluid dynamics (CFD) to analyze the thermal environment inside one room of two Roman bath buildings. By doing so, this research reveals the temperature distribution and velocity profiles inside the room of interest. -

Faculty-Led Study Abroad Course Occidental College Glee Club MUSC 121 + 122

Faculty-led Study Abroad Course Occidental College Glee Club MUSC 121 + 122 Custom Tour #1 (8 nights/10 days) Day 1 Departure via LAX Airport to Rome, Italy Day 2 Rome (L) Arrive in Rome Meet your MCI Tour Manager, who will assist the group to awaiting chartered motorcoach for transfer into Rome. Enjoy a panoramic tour of Rome’s highlights, including stops at Spanish Steps, Piazza Navona, and Trevi Fountain Welcome Lunch included Late afternoon hotel check-in Evening rehearsal Dinner, on own, and overnight at hotel Day 3 Rome (B) Breakfast at the hotel Half-day guided tour of Imperial Rome, including entrance to the Roman Forum and Colosseum. Also view the Pantheon, Baths of Caracalla, and Palatine Hill Recital at the Pantheon in Rome* Lunch, on own Performance at St. Ignazio in Rome* Dinner, on own and overnight Day 4 Rome (B) Breakfast at the hotel A half-day guided tour of Religious Rome includes Vatican City, the home of the Pope and the center of Roman Catholicism, as well as the Vatican Museums, Sistine Chapel (featuring Michelangelo's Ceiling Frescos and The Last Judgment) and St. Peter's Basilica Lunch, on own Performance at Sant’ Eustachio Church in Rome* Dinner, on own and overnight Day 5 Rome / Siena / Montecatini (B) Breakfast at the hotel, followed by check-out Transfer to Montecatini via Siena. A guided walking tour of Siena includes the famous Piazza del Campo (famous for its harmony and the famous horse races during the festival Palio delle Contrade), the Town Hall, built in the 13th century, and the Duomo (cathedral). -

Bsr Summer School 2-15(

1 BSR SUMMER SCHOOL 4-16 SEPTEMBER 2013 PROGRAMME Wednesday 4th September 16.15 Tea in courtyard; building & library tour 18.30 Introductory lecture (Robert Coates-Stephens) 19.30 Drinks 20.00 Dinner (as every day except Saturdays) Thursday 5th September THE TIBER Leave 8.30 Forum Boarium: Temples of Hercules & Portunus / 10.00 Area Sacra di S. Omobono [PERMIT] / ‘Arch of Janus’ / Arch of the Argentarii / S. Maria in Cosmedin & crypt (Ara Maxima of Hercules?) / Tiber Island / ‘Porticus Aemilia’ / 15.00 Monte Testaccio [PERMIT] 18.30 Seminar, in the BSR Library: “Approaches to Roman topography” (RCS) Friday 6th September FEEDING ROME: OSTIA Coach leaves 8.40 Ostia Antica, including 12.00 House of Diana [PERMIT] 18.30 Lecture: “The Triumph” (Ed Bispham) Saturday 7th September THE TRIUMPH OF THE REPUBLIC Leave 8.30 Pantheon / Area Sacra of Largo Argentina / Theatre of Pompey / Porticus of Octavia / Temples of Apollo Sosianus & Bellona / Theatre of Marcellus / 12.00 Three Temples of Forum Holitorium [PERMIT] / Circus Maximus / Meta Sudans / Arch of Constantine / Via Sacra: Arches of Titus, Augustus and Septimius Severus / 15.00 Mamertine prison [PERMIT] 18.30 Lecture: “The Fora” (Ed Bispham) Sunday 8th September FORUM ROMANUM & IMPERIAL FORA Leave 8.30 9.30 Forum Romanum: Introduction, central area [PERMIT] / Comitium, Atrium Vestae, Temples of Concord, Vespasian, Saturn, Castor, Divus Julius, Antoninus and Faustina, Basilicas Aemilia and Julia / Capitoline Museums & Tabularium / 14.00 Imperial Fora: Museo dei Fori Imperiali & Markets of -

The Appian Way 1 from Porta Capena to the Mausoleum of Caecilia Metella

The Appian Way 1 from Porta Capena to the Mausoleum of Caecilia Metella (Miles I-III) - Inside the Walls By bike On foot This section of the Appian Way, called “the urban section” because it was part of the city in antiquity, starts from the central archaeological area, in front of the Circus Maximus and near the Baths of Caracalla. This is where the ancient Porta Capena (Capua Gate), the original departure point of the Appian Way and the Latin Way dating back to the Republican period, was located. The urban section ends at the Porta S. Sebastiano (St. Sebastian Gate), part of the walls built in the reign of the emperor Aurelian in the 3rd century AD. The monuments described along this section are currently not included in the Appia Antica Regional Park, which begins at Porta S. Sebastiano. Nevertheless, the monumental complex of the Appian Way represents a coherent context which must be described holistically beginning in the monumental center of Rome. 1) Porta Capena The Capua Gate was part of the earliest wall of Rome, called the “Servian Wall” because its construction was traditionally attributed to the sixth king of Rome, Servius Tullius, in the middle of the 6th century BC. The most recent studies confirm the existence of a wall circuit in cappellaccio tuff that can be associated chronologically with Servius Tullius, which was later restored and enlarged in the first half of the 4th century BC. The Appian and Latin Ways both started from this gate, which was located in front of the curved end of the Circus Maximus, and then separated in the area of the large square currently dedicated to Numa Pompilius.