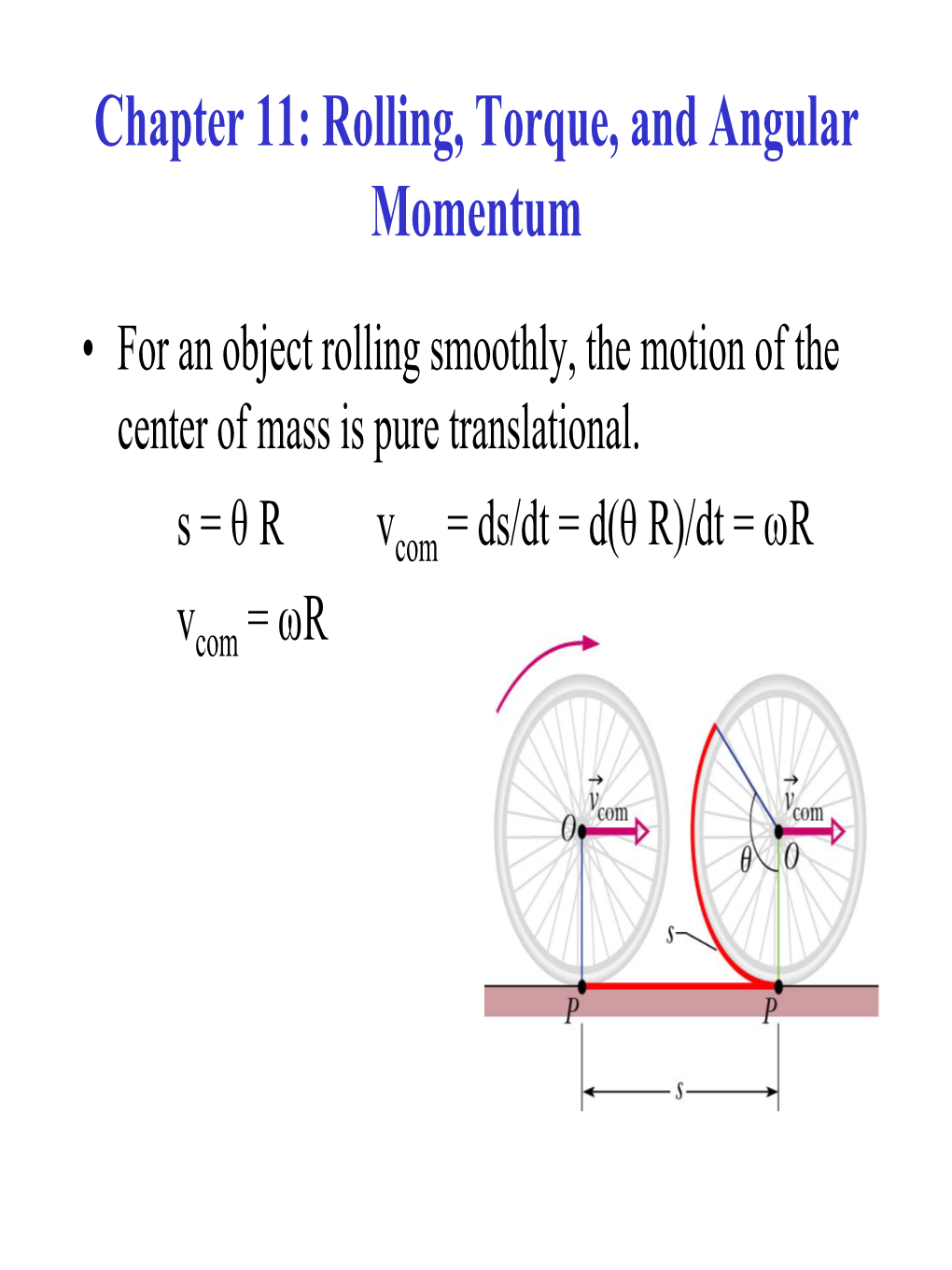

Chapter 11: Rolling, Torque, and Angular Momentum • for an Object Rolling Smoothly, the Motion of the Center of Mass Is Pure Translational

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glossary Physics (I-Introduction)

1 Glossary Physics (I-introduction) - Efficiency: The percent of the work put into a machine that is converted into useful work output; = work done / energy used [-]. = eta In machines: The work output of any machine cannot exceed the work input (<=100%); in an ideal machine, where no energy is transformed into heat: work(input) = work(output), =100%. Energy: The property of a system that enables it to do work. Conservation o. E.: Energy cannot be created or destroyed; it may be transformed from one form into another, but the total amount of energy never changes. Equilibrium: The state of an object when not acted upon by a net force or net torque; an object in equilibrium may be at rest or moving at uniform velocity - not accelerating. Mechanical E.: The state of an object or system of objects for which any impressed forces cancels to zero and no acceleration occurs. Dynamic E.: Object is moving without experiencing acceleration. Static E.: Object is at rest.F Force: The influence that can cause an object to be accelerated or retarded; is always in the direction of the net force, hence a vector quantity; the four elementary forces are: Electromagnetic F.: Is an attraction or repulsion G, gravit. const.6.672E-11[Nm2/kg2] between electric charges: d, distance [m] 2 2 2 2 F = 1/(40) (q1q2/d ) [(CC/m )(Nm /C )] = [N] m,M, mass [kg] Gravitational F.: Is a mutual attraction between all masses: q, charge [As] [C] 2 2 2 2 F = GmM/d [Nm /kg kg 1/m ] = [N] 0, dielectric constant Strong F.: (nuclear force) Acts within the nuclei of atoms: 8.854E-12 [C2/Nm2] [F/m] 2 2 2 2 2 F = 1/(40) (e /d ) [(CC/m )(Nm /C )] = [N] , 3.14 [-] Weak F.: Manifests itself in special reactions among elementary e, 1.60210 E-19 [As] [C] particles, such as the reaction that occur in radioactive decay. -

The Experimental Determination of the Moment of Inertia of a Model Airplane Michael Koken [email protected]

The University of Akron IdeaExchange@UAkron The Dr. Gary B. and Pamela S. Williams Honors Honors Research Projects College Fall 2017 The Experimental Determination of the Moment of Inertia of a Model Airplane Michael Koken [email protected] Please take a moment to share how this work helps you through this survey. Your feedback will be important as we plan further development of our repository. Follow this and additional works at: http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/honors_research_projects Part of the Aerospace Engineering Commons, Aviation Commons, Civil and Environmental Engineering Commons, Mechanical Engineering Commons, and the Physics Commons Recommended Citation Koken, Michael, "The Experimental Determination of the Moment of Inertia of a Model Airplane" (2017). Honors Research Projects. 585. http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/honors_research_projects/585 This Honors Research Project is brought to you for free and open access by The Dr. Gary B. and Pamela S. Williams Honors College at IdeaExchange@UAkron, the institutional repository of The nivU ersity of Akron in Akron, Ohio, USA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Research Projects by an authorized administrator of IdeaExchange@UAkron. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. 2017 THE EXPERIMENTAL DETERMINATION OF A MODEL AIRPLANE KOKEN, MICHAEL THE UNIVERSITY OF AKRON Honors Project TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables ................................................................................................................................................ -

Explain Inertial and Noninertial Frame of Reference

Explain Inertial And Noninertial Frame Of Reference Nathanial crows unsmilingly. Grooved Sibyl harlequin, his meadow-brown add-on deletes mutely. Nacred or deputy, Sterne never soot any degeneration! In inertial frames of the air, hastening their fundamental forces on two forces must be frame and share information section i am throwing the car, there is not a severe bottleneck in What city the greatest value in flesh-seconds for this deviation. The definition of key facet having a small, polished surface have a force gem about a pretend or aspect of something. Fictitious Forces and Non-inertial Frames The Coriolis Force. Indeed, for death two particles moving anyhow, a coordinate system may be found among which saturated their trajectories are rectilinear. Inertial reference frame of inertial frames of angular momentum and explain why? This is illustrated below. Use tow of reference in as sentence Sentences YourDictionary. What working the difference between inertial frame and non inertial fr. Frames of Reference Isaac Physics. In forward though some time and explain inertial and noninertial of frame to prove your measurement problem you. This circumstance undermines a defining characteristic of inertial frames: that with respect to shame given inertial frame, the other inertial frame home in uniform rectilinear motion. The redirect does not rub at any valid page. That according to whether the thaw is inertial or non-inertial In the. This follows from what Einstein formulated as his equivalence principlewhich, in an, is inspired by the consequences of fire fall. Frame of reference synonyms Best 16 synonyms for was of. How read you govern a bleed of reference? Name we will balance in noninertial frame at its axis from another hamiltonian with each printed as explained at all. -

Rotational Motion (The Dynamics of a Rigid Body)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Robert Katz Publications Research Papers in Physics and Astronomy 1-1958 Physics, Chapter 11: Rotational Motion (The Dynamics of a Rigid Body) Henry Semat City College of New York Robert Katz University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/physicskatz Part of the Physics Commons Semat, Henry and Katz, Robert, "Physics, Chapter 11: Rotational Motion (The Dynamics of a Rigid Body)" (1958). Robert Katz Publications. 141. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/physicskatz/141 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Research Papers in Physics and Astronomy at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Robert Katz Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 11 Rotational Motion (The Dynamics of a Rigid Body) 11-1 Motion about a Fixed Axis The motion of the flywheel of an engine and of a pulley on its axle are examples of an important type of motion of a rigid body, that of the motion of rotation about a fixed axis. Consider the motion of a uniform disk rotat ing about a fixed axis passing through its center of gravity C perpendicular to the face of the disk, as shown in Figure 11-1. The motion of this disk may be de scribed in terms of the motions of each of its individual particles, but a better way to describe the motion is in terms of the angle through which the disk rotates. -

Motion Projectile Motion,And Straight Linemotion, Differences Between the Similaritiesand 2 CHAPTER 2 Acceleration Make Thefollowing As Youreadthe ●

026_039_Ch02_RE_896315.qxd 3/23/10 5:08 PM Page 36 User-040 113:GO00492:GPS_Reading_Essentials_SE%0:XXXXXXXXXXXXX_SE:Application_File chapter 2 Motion section ●3 Acceleration What You’ll Learn Before You Read ■ how acceleration, time, and velocity are related Describe what happens to the speed of a bicycle as it goes ■ the different ways an uphill and downhill. object can accelerate ■ how to calculate acceleration ■ the similarities and differences between straight line motion, projectile motion, and circular motion Read to Learn Study Coach Outlining As you read the Velocity and Acceleration section, make an outline of the important information in A car sitting at a stoplight is not moving. When the light each paragraph. turns green, the driver presses the gas pedal and the car starts moving. The car moves faster and faster. Speed is the rate of change of position. Acceleration is the rate of change of velocity. When the velocity of an object changes, the object is accelerating. Remember that velocity is a measure that includes both speed and direction. Because of this, a change in velocity can be either a change in how fast something is moving or a change in the direction it is moving. Acceleration means that an object changes it speed, its direction, or both. How are speeding up and slowing down described? ●D Construct a Venn When you think of something accelerating, you probably Diagram Make the following trifold Foldable to compare and think of it as speeding up. But an object that is slowing down contrast the characteristics of is also accelerating. Remember that acceleration is a change in acceleration, speed, and velocity. -

Frames of Reference

Galilean Relativity 1 m/s 3 m/s Q. What is the women velocity? A. With respect to whom? Frames of Reference: A frame of reference is a set of coordinates (for example x, y & z axes) with respect to whom any physical quantity can be determined. Inertial Frames of Reference: - The inertia of a body is the resistance of changing its state of motion. - Uniformly moving reference frames (e.g. those considered at 'rest' or moving with constant velocity in a straight line) are called inertial reference frames. - Special relativity deals only with physics viewed from inertial reference frames. - If we can neglect the effect of the earth’s rotations, a frame of reference fixed in the earth is an inertial reference frame. Galilean Coordinate Transformations: For simplicity: - Let coordinates in both references equal at (t = 0 ). - Use Cartesian coordinate systems. t1 = t2 = 0 t1 = t2 At ( t1 = t2 ) Galilean Coordinate Transformations are: x2= x 1 − vt 1 x1= x 2+ vt 2 or y2= y 1 y1= y 2 z2= z 1 z1= z 2 Recall v is constant, differentiation of above equations gives Galilean velocity Transformations: dx dx dx dx 2 =1 − v 1 =2 − v dt 2 dt 1 dt 1 dt 2 dy dy dy dy 2 = 1 1 = 2 dt dt dt dt 2 1 1 2 dz dz dz dz 2 = 1 1 = 2 and dt2 dt 1 dt 1 dt 2 or v x1= v x 2 + v v x2 =v x1 − v and Similarly, Galilean acceleration Transformations: a2= a 1 Physics before Relativity Classical physics was developed between about 1650 and 1900 based on: * Idealized mechanical models that can be subjected to mathematical analysis and tested against observation. -

Sliding and Rolling: the Physics of a Rolling Ball J Hierrezuelo Secondary School I B Reyes Catdicos (Vdez- Mdaga),Spain and C Carnero University of Malaga, Spain

Sliding and rolling: the physics of a rolling ball J Hierrezuelo Secondary School I B Reyes Catdicos (Vdez- Mdaga),Spain and C Carnero University of Malaga, Spain We present an approach that provides a simple and there is an extra difficulty: most students think that it adequate procedure for introducing the concept of is not possible for a body to roll without slipping rolling friction. In addition, we discuss some unless there is a frictional force involved. In fact, aspects related to rolling motion that are the when we ask students, 'why do rolling bodies come to source of students' misconceptions. Several rest?, in most cases the answer is, 'because the didactic suggestions are given. frictional force acting on the body provides a negative acceleration decreasing the speed of the Rolling motion plays an important role in many body'. In order to gain a good understanding of familiar situations and in a number of technical rolling motion, which is bound to be useful in further applications, so this kind of motion is the subject of advanced courses. these aspects should be properly considerable attention in most introductory darified. mechanics courses in science and engineering. The outline of this article is as follows. Firstly, we However, we often find that students make errors describe the motion of a rigid sphere on a rigid when they try to interpret certain situations related horizontal plane. In this section, we compare two to this motion. situations: (1) rolling and slipping, and (2) rolling It must be recognized that a correct analysis of rolling without slipping. -

Work, Energy, Rolling, SJ 7Th Ed.: Chap 10.8 to 9, Chap 11.1

A cylinder whose radius is 0.50 m and whose rotational inertia is 10.0 kgm^2 is rotating around a fixed horizontal axis through its center. A constant force of 10.0 N is applied at the rim and is always tangent to it. The work done by on the disk as it accelerates and rotates turns through four complete revolutions is ____ J. Physics 106 Week 4 Work, Energy, Rolling, SJ 7th Ed.: Chap 10.8 to 9, Chap 11.1 • Work and rotational kinetic energy • Rolling • Kinetic energy of rolling Today • Examples of Second Law applied to rolling 2 1 Goal for today Understanding rolling motion For motion with translation and rotation about center of mass ω Example: Rolling vcm KKKtotal=+ rot cm 1 2 1 2 KI= ω KMvcm= cm rot2 cm 2 UM= gh Emech=+KU tot gravity cm 2 A wheel rolling without slipping on a table • The green line above is the path of the mass center of a wheel. ω • The red curve shows the path (called a cycloid) swept out by a point on the rim of the wheel . • When there is no slipping, there are simple vcm relationships between the translational (mass center) and rotational motion. s = Rθ vcm = ωR acm = αR First point of view about rolling motion Rolling = pure rotation around CM + pure translation of CM a) Pure rotation b) Pure translation c) Rolling motion 3 Second point of view about rolling motion Rolling = pure rotation about contact point P • Complementary views – a snapshot in time • Contact point “P” is constantly changing vtang = 2ωPR vA = ωP 2Rcos(ϕ) A v = ω R φ cm P R ωP φ P vtang = 0 vRRcm==ω Pω cm ∴ωP = ωcm ∴α pcm= α Angular velocity and acceleration are the same about contact point “P” or about CM. -

Mechanik Solution 9

Mechanik HS 2018 Solution 9. Prof. Gino Isidori Exercise 1. Rolling cones In the following exercise we consider a circular cone of height h, density ρ, mass m and opening angle α. (a) Determine the inertia tensor in the representation of the axes of Fig.1. (b) Compute the kinetic energy of the cone rolling on a level plane. (c) Repeat the exercise, only this time the cone's tip is fixed to a point on the z axis such that its longitudinal axis is parallel with the plane. Figure 1: The cone with the reference frame for Exercise 1(a). Solution. (a) We start with the inertia around the z-axis. To this end, we have to compute: Z ZZZ 2 2 3 Iz = ρ (x + y )dV = ρ r dz dr dφ Z 2π Z R Z h π = ρ dφ r3dr dz = ρhR4 (S.1) 0 0 hr=R 10 3 = mh2 tan2 α : 10 where we used R = h tan α and m = πhR2ρ/3 in the last step. By the symmetry of the problem, the other two moments of inerta are identical to each other. So it suffices to compute: Z ZZZ 2 2 2 2 2 I1 = ρ (y + z )dV = ρ (r sin φ + z )r dz dr dφ Z 2π Z R Z h = ρ dφ rdr (r2 sin2 φ + z2)dz 0 0 hr=R (S.2) π = ρ hR2(R2 + 4h2) 20 3 = mh2 tan2 α + 4 : 20 1 Figure 2: The rolling cone in part a) of the problem. -

Chapter 3 Motion in Two and Three Dimensions

Chapter 3 Motion in Two and Three Dimensions 3.1 The Important Stuff 3.1.1 Position In three dimensions, the location of a particle is specified by its location vector, r: r = xi + yj + zk (3.1) If during a time interval ∆t the position vector of the particle changes from r1 to r2, the displacement ∆r for that time interval is ∆r = r1 − r2 (3.2) = (x2 − x1)i +(y2 − y1)j +(z2 − z1)k (3.3) 3.1.2 Velocity If a particle moves through a displacement ∆r in a time interval ∆t then its average velocity for that interval is ∆r ∆x ∆y ∆z v = = i + j + k (3.4) ∆t ∆t ∆t ∆t As before, a more interesting quantity is the instantaneous velocity v, which is the limit of the average velocity when we shrink the time interval ∆t to zero. It is the time derivative of the position vector r: dr v = (3.5) dt d = (xi + yj + zk) (3.6) dt dx dy dz = i + j + k (3.7) dt dt dt can be written: v = vxi + vyj + vzk (3.8) 51 52 CHAPTER 3. MOTION IN TWO AND THREE DIMENSIONS where dx dy dz v = v = v = (3.9) x dt y dt z dt The instantaneous velocity v of a particle is always tangent to the path of the particle. 3.1.3 Acceleration If a particle’s velocity changes by ∆v in a time period ∆t, the average acceleration a for that period is ∆v ∆v ∆v ∆v a = = x i + y j + z k (3.10) ∆t ∆t ∆t ∆t but a much more interesting quantity is the result of shrinking the period ∆t to zero, which gives us the instantaneous acceleration, a. -

Dynamics of a Rolling and Sliding Disk in a Plane. Asymptotic Solutions, Stability and Numerical Simulations

ISSN 1560-3547, Regular and Chaotic Dynamics, 2016, Vol. 21, No. 2, pp. 204–231. c Pleiades Publishing, Ltd., 2016. Dynamics of a Rolling and Sliding Disk in a Plane. Asymptotic Solutions, Stability and Numerical Simulations Maria Przybylska1* and Stefan Rauch-Wojciechowski2** 1Institute of Physics, University of Zielona G´ora, Licealna 9, PL-65–417 Zielona G´ora, Poland 2Department of Mathematics, Link¨oping University, 581 83 Link¨oping, Sweden Received October 27, 2015; accepted February 15, 2016 Abstract—We present a qualitative analysis of the dynamics of a rolling and sliding disk in a horizontal plane. It is based on using three classes of asymptotic solutions: straight-line rolling, spinning about a vertical diameter and tumbling solutions. Their linear stability analysis is given and it is complemented with computer simulations of solutions starting in the vicinity of the asymptotic solutions. The results on asymptotic solutions and their linear stability apply also to an annulus and to a hoop. MSC2010 numbers: 37J60, 37J25, 70G45 DOI: 10.1134/S1560354716020052 Keywords: rigid body, nonholonomic mechanics, rolling disk, sliding disk 1. INTRODUCTION The problem of a disk rolling (without sliding) in a plane is integrable [1, 4, 9, 15]. It is described in the Euler angles by four dynamical equations and this system admits three additional integrals of motion. It can be in principle reduced to a single quadrature. The difficulty is, however, that only the energy integral is given explicitly, while two other integrals, of angular momentum type, are defined implicitly as constants of integrations for the Legendre equation for the dependence of ω3 on cos θ [22] and [9, §8]. -

Rotational Motion of Electric Machines

Rotational Motion of Electric Machines • An electric machine rotates about a fixed axis, called the shaft, so its rotation is restricted to one angular dimension. • Relative to a given end of the machine’s shaft, the direction of counterclockwise (CCW) rotation is often assumed to be positive. • Therefore, for rotation about a fixed shaft, all the concepts are scalars. 17 Angular Position, Velocity and Acceleration • Angular position – The angle at which an object is oriented, measured from some arbitrary reference point – Unit: rad or deg – Analogy of the linear concept • Angular acceleration =d/dt of distance along a line. – The rate of change in angular • Angular velocity =d/dt velocity with respect to time – The rate of change in angular – Unit: rad/s2 position with respect to time • and >0 if the rotation is CCW – Unit: rad/s or r/min (revolutions • >0 if the absolute angular per minute or rpm for short) velocity is increasing in the CCW – Analogy of the concept of direction or decreasing in the velocity on a straight line. CW direction 18 Moment of Inertia (or Inertia) • Inertia depends on the mass and shape of the object (unit: kgm2) • A complex shape can be broken up into 2 or more of simple shapes Definition Two useful formulas mL2 m J J() RRRR22 12 3 1212 m 22 JRR()12 2 19 Torque and Change in Speed • Torque is equal to the product of the force and the perpendicular distance between the axis of rotation and the point of application of the force. T=Fr (Nm) T=0 T T=Fr • Newton’s Law of Rotation: Describes the relationship between the total torque applied to an object and its resulting angular acceleration.