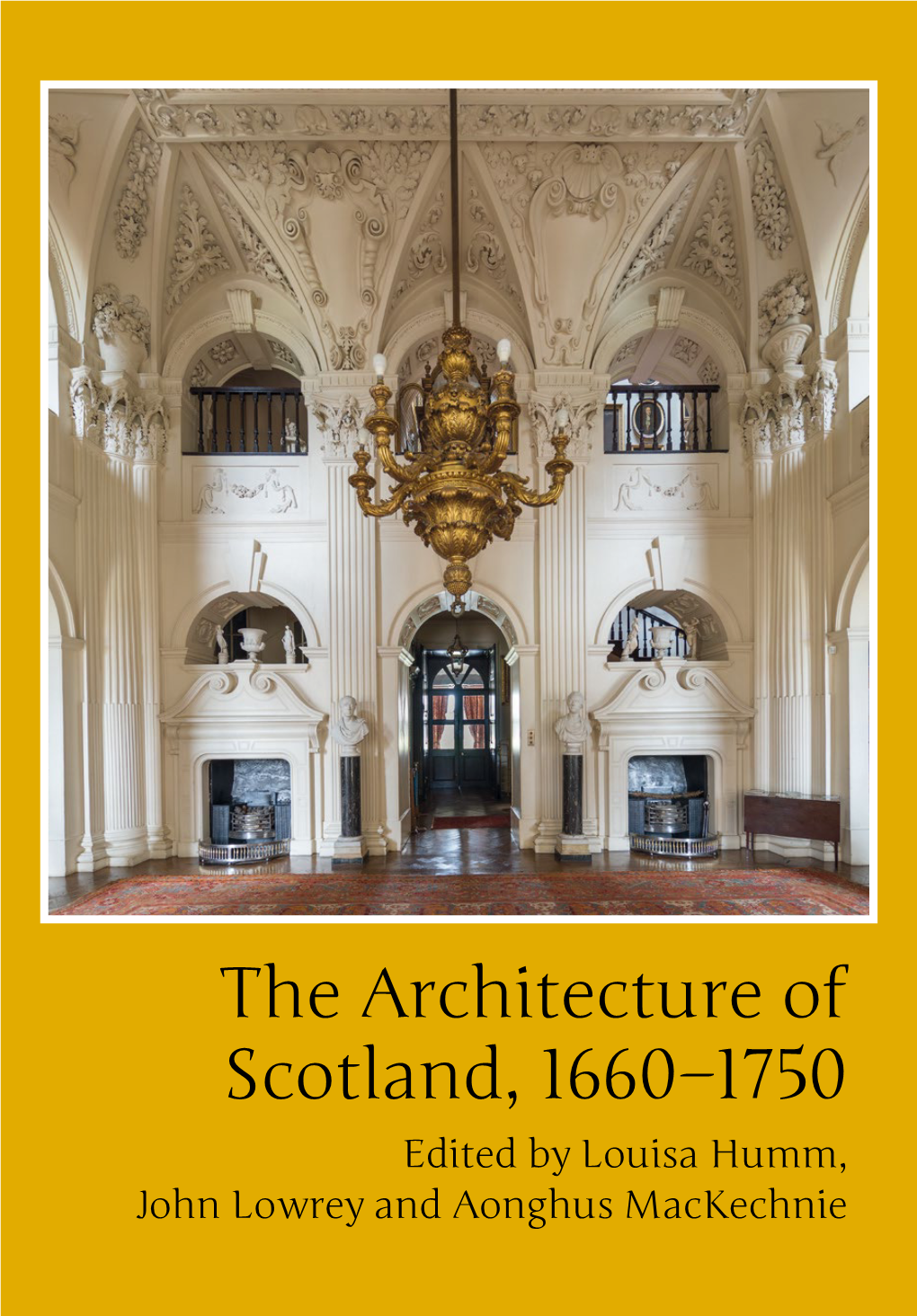

The Architecture of Scotland, 1660–1750

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Passion for Opera the DUCHESS and the GEORGIAN STAGE

A Passion for Opera THE DUCHESS AND THE GEORGIAN STAGE A Passion for Opera THE DUCHESS AND THE GEORGIAN STAGE PAUL BOUCHER JEANICE BROOKS KATRINA FAULDS CATHERINE GARRY WIEBKE THORMÄHLEN Published to accompany the exhibition A Passion for Opera: The Duchess and the Georgian Stage Boughton House, 6 July – 30 September 2019 http://www.boughtonhouse.co.uk https://sound-heritage.soton.ac.uk/projects/passion-for-opera First published 2019 by The Buccleuch Living Heritage Trust The right of Paul Boucher, Jeanice Brooks, Katrina Faulds, Catherine Garry, and Wiebke Thormählen to be identified as the authors of the editorial material and as the authors for their individual chapters, has been asserted in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the authors. ISBN: 978-1-5272-4170-1 Designed by pmgd Printed by Martinshouse Design & Marketing Ltd Cover: Thomas Gainsborough (1727-1788), Lady Elizabeth Montagu, Duchess of Buccleuch, 1767. Portrait commemorating the marriage of Elizabeth Montagu, daughter of George, Duke of Montagu, to Henry, 3rd Duke of Buccleuch. (Cat.10). © Buccleuch Collection. Backdrop: Augustus Pugin (1769-1832) and Thomas Rowlandson (1757-1827), ‘Opera House (1800)’, in Rudolph Ackermann, Microcosm of London (London: Ackermann, [1808-1810]). © The British Library Board, C.194.b.305-307. Inside cover: William Capon (1757-1827), The first Opera House (King’s Theatre) in the Haymarket, 1789. -

Newsletter No.25 October 2008 Notes from The

Newsletter No.25 October 2008 One episode in fifty years of railway warfare: the Tay Bridge collapse of 1879 Notes from the Chair and Archive News p2 The Railway Battle for Scotland p4 Abernyte: the quiet revolution p10 Drummond Castle and Gardens p12 Crossword p16 Notes from the Chair Since our last Newsletter we have enjoyed (or perhaps endured?) the summer, during which the Friends participated in a variety of activities, notably our outing to the Gardens and Keep at Drum- mond Castle on 21 July. It was great fun, enhanced by sunny, warm weather and Alan Kinnaird has written a most interesting and detailed account on pages 12-15. The Voice of Alyth kindly described our presentation of A Mosaic of Wartime Alyth on Thursday 5 June as "fascinating and very well-received". Certainly, those who attended were responsive and we were given some intriguing information about events in Alyth during the Second World War. A couple of the townsfolk have volunteered to let us record their memories on tape for an oral history project. On our side, this will involve talking to the volunteers concerned, recording the conversation and - arguably the hardest part! - transcribing it. In accordance with the maxim that many hands make light work, we shall be asking Friends to volunteer to participate in this pro- ject. Other summer activities, all most enjoyable, included the Family History Day in the AK Bell Li- brary on 23 August, and the Rait Highland Games on the 30th, where Hilary Wright made a hit teaching children how to write with quill pens. -

The Avarice and Ambition of William Benson’, the Georgian Group Journal, Vol

Anna Eavis, ‘The avarice and ambition of William Benson’, The Georgian Group Journal, Vol. XII, 2002, pp. 8–37 TEXT © THE AUTHORS 2002 THE AVARICE AND AMBITION OF WILLIAM BENSON ANNA EAVIS n his own lifetime William Benson’s moment of probably motivated by his desire to build a neo- Ifame came in January , as the subject of an Palladian parliament house. anonymous pamphlet: That Benson had any direct impact on the spread of neo-Palladian ideas other than his patronage of I do therefore with much contrition bewail my making Campbell through the Board of Works is, however, of contracts with deceitfulness of heart … my pride, unlikely. Howard Colvin’s comprehensive and my arrogance, my avarice and my ambition have been my downfall .. excoriating account of Benson’s surveyorship shows only too clearly that his pre-occupations were To us, however, he is also famous for building a financial and self-motivated, rather than aesthetic. precociously neo-Palladian house in , as well He did not publish on architecture, neo-Palladian or as infamous for his corrupt, incompetent and otherwise and, with the exception of Wilbury, consequently brief tenure as Surveyor-General of the appears to have left no significant buildings, either in King’s Works, which ended in his dismissal for a private or official capacity. This absence of a context deception of King and Government. Wilbury, whose for Wilbury makes the house even more startling; it elevation was claimed to be both Jonesian and appears to spring from nowhere and, as far as designed by Benson, and whose plan was based on Benson’s architectural output is concerned, to lead that of the Villa Poiana, is notable for apparently nowhere. -

The Early Career of Thomas Craig, Advocate

Finlay, J. (2004) The early career of Thomas Craig, advocate. Edinburgh Law Review, 8 (3). pp. 298-328. ISSN 1364-9809 http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/37849/ Deposited on: 02 April 2012 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk EdinLR Vol 8 pp 298-328 The Early Career of Thomas Craig, Advocate John Finlay* Analysis of the clients of the advocate and jurist Thomas Craig of Riccarton in a formative period of his practice as an advocate can be valuable in demonstrating the dynamics of a career that was to be noteworthy not only in Scottish but in international terms. However, it raises the question of whether Craig’s undoubted reputation as a writer has led to a misleading assessment of his prominence as an advocate in the legal profession of his day. A. INTRODUCTION Thomas Craig (c 1538–1608) is best known to posterity as the author of Jus Feudale and as a commissioner appointed by James VI in 1604 to discuss the possi- bility of a union of laws between England and Scotland.1 Following from the latter enterprise, he was the author of De Hominio (published in 1695 as Scotland”s * Lecturer in Law, University of Glasgow. The research required to complete this article was made possible by an award under the research leave scheme of the Arts and Humanities Research Board and the author is very grateful for this support. He also wishes to thank Dr Sharon Adams, Mr John H Ballantyne, Dr Julian Goodare and Mr W D H Sellar for comments on drafts of this article, the anonymous reviewer for the Edinburgh Law Review, and also the members of the Scottish Legal History Group to whom an early version of this paper was presented in October 2003. -

Scottish Football Association List of Suspensions Issue No

SCOTTISH FOOTBALL ASSOCIATION LIST OF SUSPENSIONS ISSUE NO. 31: FRIDAY 08 FEBRUARY 2019 IMPORTANT – THIS LIST DOES NOT SUPERSEDE THE FORMAL NOTIFICATION OF PLAYER SUSPENSIONS TO CLUBS BY THE ASSOCIATION, VIA THE CLUB EXTRANET, AND IS INTENDED ONLY FOR USE AS AN ADDITIONAL CROSS-REFERENCE IN THE MONITORING AND OBSERVING, BY CLUBS, OF SUSPENSIONS IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE DISCIPLINARY PROCEDURES. IT IS THE RESPONSIBILITY OF CLUBS TO ENSURE THAT SUSPENSIONS ARE SERVED IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE DISCIPLINARY PROCEDURES. SHOULD ANY CLUB HAVE AN ENQUIRY REGARDING A PLAYER’S DISCIPLINARY POSITION, PLEASE CONTACT THE DISCIPLINARY DEPARTMENT ON 0141 616 6018 or 07702 864 165. PLEASE CHECK ALL SECTIONS OF THIS LIST AND CONTACT THE DISIPLINARY DEPARTMENT IF YOU HAVE REGISTERED A NEW PLAYER FOR YOUR CLUB SUSPENSIONS INCURRED BETWEEN 31/01/2019 TO 07/02/2019 DATE INCURRED PLAYER (CLUB) SUSPENSION SPFL - SCOTTISH PREMIERSHIP 30/01/2019 276256 - EUAN DEVENEY (KILMARNOCK F.C.) 1 CAS U18 MATCH FROM 13/02/2019 01/02/2019 386086 - DEAN RITCHIE (HEART OF MIDLOTHIAN F.C.) 1 CAS U18 MATCH FROM 15/02/2019 03/02/2019 423124 - KRISTOFFER VASSBAKK AJER (CELTIC F.C.) 1 SPFL FIRST TEAM LEAGUE MATCH IMMEDIATE 06/02/2019 124842 - SCOTT FRASER MCKENNA (ABERDEEN F.C.) 2 FIRST TEAM MATCHES IMMEDIATE AND 1 SPFL FIRST TEAM LEAGUE MATCH FROM 20/02/2019 SPFL – CHAMPIONSHIP 30/01/2019 260210 - DEAN WATSON (PARTICK THISTLE F.C.) (T) 1 CAS U18 MATCH FROM 13/02/2019 02/02/2019 425359 - DAVIS KEILLOR-DUNN (FALKIRK F.C.) 1 SPFL FIRST TEAM LEAGUE MATCH IMMEDIATE 06/02/2019 201729 - BEN -

Walter Scott's Kelso

Walter Scott’s Kelso The Untold Story Published by Kelso and District Amenity Society. Heritage Walk Design by Icon Publications Ltd. Printed by Kelso Graphics. Cover © 2005 from a painting by Margaret Peach. & Maps Walter Scott’s Kelso Fifteen summers in the Borders Scott and Kelso, 1773–1827 The Kelso inheritance which Scott sold The Border Minstrelsy connection Scott’s friends and relations & the Ballantyne Family The destruction of Scott’s memories KELSO & DISTRICT AMENITY SOCIETY Text & photographs by David Kilpatrick Cover & illustrations by Margaret Peach IR WALTER SCOTT’s connection with Kelso is more important than popular histories and guide books lead you to believe. SScott’s signature can be found on the deeds of properties along the Mayfield, Hempsford and Rosebank river frontage, in transactions from the late 1790s to the early 1800s. Scott’s letters and journal, and the biography written by his son-in-law John Gibson Lockhart, contain all the information we need to learn about Scott’s family links with Kelso. Visiting the Borders, you might believe that Scott ‘belongs’ entirely to Galashiels, Melrose and Selkirk. His connection with Kelso has been played down for almost 200 years. Kelso’s Scott is the young, brilliant, genuinely unknown Walter who discovered Border ballads and wrote the Minstrelsy, not the ‘Great Unknown’ literary baronet who exhausted his phenomenal energy 30 years later saving Abbotsford from ruin. Guide books often say that Scott spent a single summer convalescing in the town, or limit references to his stays at Sandyknowe Farm near Smailholm Tower. The impression given is of a brief acquaintance in childhood. -

University of Dundee Unit of Assessment: 30 History Title of Case

Impact case study (REF3b) Institution: University of Dundee Unit of Assessment: 30 History Title of case study: Urban and Architectural History of Scotland, c.1500-c.1800 1. Summary of the impact (indicative maximum 100 words) The focus of the research in question has been to establish how far the architectural and urban culture of Scotland before the Union in 1707 was ‘European’ and the consequences for Scotland’s architecture after 1707 within the UK, including the issue of its assimilation with that of the rest of Britain. Initially the work, beginning in the later 1990s, concentrated on particular Scottish cities, notably Dundee and Edinburgh, more recently widening to include a large sample of Scotland’s other smaller towns. The impact of what is a major body of diverse but inter-related research (at the heart of which are buildings and the built environment) is demonstrated at several levels, through local dissemination and community engagement, through to changing public discourse at national level about much of Scotland’s architectural heritage and its implications for today. This has been achieved through the role of the lead researcher (Charles McKean) in major advisory bodies, as chairman of Edinburgh World Heritage Trust (2006-2012) to the Historic Environment Advisory Council for Scotland, and on the Scottish Committee of the Heritage Lottery Fund (Section 5: 1,2,3,4,5 and 8). 2. Underpinning research (indicative maximum 500 words) The lead researcher, Charles McKean, was Professor of Scottish Architectural History since 1997 until his death in October 2013. His examination of the European origins of Scots cities (such as Dundee, with its Baltic features) highlighted significant contrasts with the ‘British’ form of the ‘New Towns’ of places such as Edinburgh and Glasgow. -

The Daniel Wilson Scrapbook

The Daniel Wilson Scrapbook Illustrations of Edinburgh and other material collected by Sir Daniel Wilson, some of which he used in his Memorials of Edinburgh in the olden time (Edin., 1847). The following list gives possible sources for the items; some prints were published individually as well as appearing as part of larger works. References are also given to their use in Memorials. Quick-links within this list: Box I Box II Box III Abbreviations and notes Arnot: Hugo Arnot, The History of Edinburgh (1788). Bann. Club: Bannatyne Club. Beattie, Caledonia illustrated: W. Beattie, Caledonia illustrated in a series of views [ca. 1840]. Beauties of Scotland: R. Forsyth, The Beauties of Scotland (1805-8). Billings: R.W. Billings, The Baronial and ecclesiastical Antiquities of Scotland (1845-52). Black (1843): Black’s Picturesque tourist of Scotland (1843). Black (1859): Black’s Picturesque tourist of Scotland (1859). Edinburgh and Mid-Lothian (1838). Drawings by W.B. Scott, engraved by R. Scott. Some of the engravings are dated 1839. Edinburgh delineated (1832). Engravings by W.H. Lizars, mostly after drawings by J. Ewbank. They are in two series, each containing 25 numbered prints. See also Picturesque Views. Geikie, Etchings: Walter Geikie, Etchings illustrative of Scottish character and scenery, new edn [1842?]. Gibson, Select Views: Patrick Gibson, Select Views in Edinburgh (1818). Grose, Antiquities: Francis Grose, The Antiquities of Scotland (1797). Hearne, Antiquities: T. Hearne, Antiquities of Great Britain illustrated in views of monasteries, castles and churches now existing (1807). Heriot’s Hospital: Historical and descriptive account of George Heriot’s Hospital. With engravings by J. -

Biographical Appendix

Biographical Appendix The following women are mentioned in the text and notes. Abney- Hastings, Flora. 1854–1887. Daughter of 1st Baron Donington and Edith Rawdon- Hastings, Countess of Loudon. Married Henry FitzAlan Howard, 15th Duke of Norfolk, 1877. Acheson, Theodosia. 1882–1977. Daughter of 4th Earl of Gosford and Louisa Montagu (daughter of 7th Duke of Manchester and Luise von Alten). Married Hon. Alexander Cadogan, son of 5th Earl of Cadogan, 1912. Her scrapbook of country house visits is in the British Library, Add. 75295. Alten, Luise von. 1832–1911. Daughter of Karl von Alten. Married William Montagu, 7th Duke of Manchester, 1852. Secondly, married Spencer Cavendish, 8th Duke of Devonshire, 1892. Grandmother of Alexandra, Mary, and Theodosia Acheson. Annesley, Katherine. c. 1700–1736. Daughter of 3rd Earl of Anglesey and Catherine Darnley (illegitimate daughter of James II and Catherine Sedley, Countess of Dorchester). Married William Phipps, 1718. Apsley, Isabella. Daughter of Sir Allen Apsley. Married Sir William Wentworth in the late seventeenth century. Arbuthnot, Caroline. b. c. 1802. Daughter of Rt. Hon. Charles Arbuthnot. Stepdaughter of Harriet Fane. She did not marry. Arbuthnot, Marcia. 1804–1878. Daughter of Rt. Hon. Charles Arbuthnot. Stepdaughter of Harriet Fane. Married William Cholmondeley, 3rd Marquess of Cholmondeley, 1825. Aston, Barbara. 1744–1786. Daughter and co- heir of 5th Lord Faston of Forfar. Married Hon. Henry Clifford, son of 3rd Baron Clifford of Chudleigh, 1762. Bannister, Henrietta. d. 1796. Daughter of John Bannister. She married Rev. Hon. Brownlow North, son of 1st Earl of Guilford, 1771. Bassett, Anne. Daughter of Sir John Bassett and Honor Grenville. -

Eric and Pat Walker Morning Service Sundays at 10.30 Am ALL

October 2020 Send news to : [email protected] Delivered free to every home in Letham and district by Dunnichen Letham and Kirkden Church of Scotland (Registered Scottish Charity 0003833) Times they are a changing! How true are those words from an old song! Did and his passengers and not particularly good for the we ever think things could have gone this far when vehicle either. The intention is to give the driver we are not even allowed to sing in Church? time to think about things that matter. Things like Awareness of unseen dangers are making us take what lies ahead of him, road signs that are there to precautions like at no other time. We are being warn him of any danger, of other road users and of made to think of how we might how he should behave towards them. Sometimes protect ourselves and others all of us on the road of life need while we are having to change to slow down and that is what our habits. Over the years there part of Sunday is all about for are many things that have been Christians. ‘Take your time,’ it put in place by our councils and says. Take care and think about governments in order to keep us the things that really matter. safe and one of those things are Think about God and the guide- ‘sleeping policemen’. Now in lines we find in his word; think villages such as Letham, there is of those who travel the road with not a great deal of call for them us; think of how we should treat but in the cities, well things are a each other. -

Edinburgh's Urban Enlightenment and George IV

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Edinburgh’s Urban Enlightenment and George IV: Staging North Britain, 1752-1822 Student Dissertation How to cite: Pirrie, Robert (2019). Edinburgh’s Urban Enlightenment and George IV: Staging North Britain, 1752-1822. Student dissertation for The Open University module A826 MA History part 2. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2019 The Author https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Version: Redacted Version of Record Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk Edinburgh’s Urban Enlightenment and George IV: Staging North Britain, 1752-1822 Robert Pirrie LL.B (Hons) (Glasgow University) A dissertation submitted to The Open University for the degree of MA in History January 2019 WORD COUNT: 15,993 Robert Pirrie– A826 – Dissertation Abstract From 1752 until the visit of George IV in 1822, Edinburgh expanded and improved through planned urban development on classical principles. Historians have broadly endorsed accounts of the public spectacles and official functions of the king’s sojourn in the city as ersatz Highland pageantry projecting a national identity devoid of the Scottish Lowlands. This study asks if evidence supports an alternative interpretation locating the proceedings as epochal royal patronage within urban cultural history. Three largely discrete fields of historiography are examined: Peter Borsay’s seminal study of English provincial towns, 1660-1770; Edinburgh’s urban history, 1752-1822; and George IV’s 1822 visit. -

Douglas5 OCR.Pdf

.1 :; 1.~ " I ! I ';:::: I ",.. Sir Andrew Douglas of Herdmanston (1259) f"'. I ...William de Douglas (1350) I Sir James Douglas of Lothian (I~) , --I I Sir William Do ..( I.t}thian Sir John Douglas of Dalkeith (Kl1ight of : talalc), (13(x)-I30i3) I I I ~ ! Sir James Dougla.o; Sir Henry Douglas ! uf Valkeith and ~Iorton of Luron and Loch Leven .! '~r I;; SirJamcs, 1st LordI Dalkeith (1450) Sir William of Loch Leven , " I 1 :' .t James, 2nd I..,rd l>alkeith (1456) Sir Henry of Loch Leven \ .j I I ~ ~ Janles, 1st Earl of Morton (IroJ) Sir Robert of Loch Leven r IT ..I --r Sir Robert I!of Loch I.even Nicho!a.o;Dougla! ,f~ns John, 2nd Earl of Morton (Iiilii) I (y !r !)rothcr) I I I I James, 3rd Earl of ~Iorton (I55:J) William, 8th Earl flf Morton George Douglas, 8$.o;istedMary Queen~ John i>Ouglasof", .1 (d. 1606) of Scots to escape from Loch Leven ofrchi1X\ld Kilspindie Douglas Mary_cCampl~11I MargaretII Beatrice I~lizabethI I1 I I I . - Bly = James Douglas, Robert James Sir James Douglas Archibald Regent of I of Smithfield. I t Scotland William, Douglases .9th Earl of Morton of Kirknes.~ ,- , j --, -' ---'-: ~~;- I i -I I I '"- ir Robert Douglas .~ .Robert, I~h Sir James, 12th George, 5th of Glenbirvie 1 Earl of Morton Earl of Morton Earl of Morton I '.. " " I I I I .'-1) William, 11th I I James, 6th .William Douglas Joh, Campbell ofl"{dside Earl of Morton Jame,s. Robert, Earl of Morton I ; I j'.