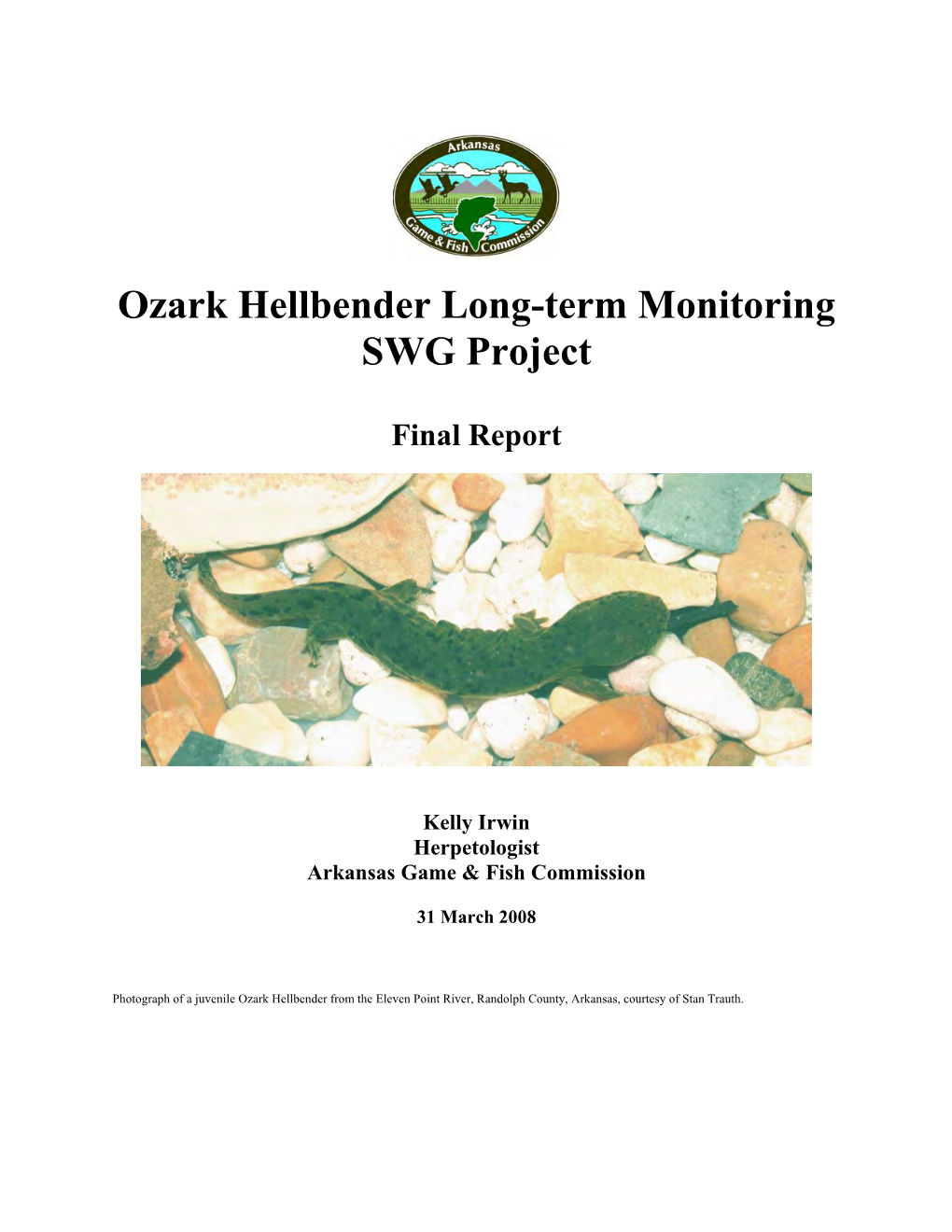

Ozark Hellbender Long-Term Monitoring SWG Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Legacy of Neglect: the Ozark National Scenic Riverways

A Legacy of Neglect: The Ozark National Scenic Riverways Susan Flader Missouri’s Current River and its tributary, the Jacks Fork, were the nation’s first fed- erally protected rivers. Congressionally authorized in 1964 as the Ozark National Scenic Riverways (ONSR), they served as a prototype for the National Wild and Scenic Rivers Act of 1968. But in May 2011 ONSR was identified by American Rivers as one of America’s ten most endangered rivers, owing to a history of inadequate management by the National Park Service (NPS). The spring-fed, bluff-lined Current and Jacks Fork are the preeminent “float streams” in a state where floating, fishing, and camping by johnboat or canoe have long been favorite pastimes (Figure 1). The state’s first Republican governor since Reconstruction, Herbert Hadley, led well-publicized float trips on Current River as early as 1909 in an effort to pro- mote tourism and build support for a state park system. When Missouri acquired its first state parks in 1924, they included Round Spring and Big Spring on the Current River and Alley Spring on the Jacks Fork. The rivers early attracted admirers from afar; Aldo Leopold came from Wisconsin in 1926 to float the Current from Van Buren to Doniphan with his brothers (Leopold 1953; Figure 2), then in 1929 bought a shanty on its bank as a base for annual hunts, years before he acquired his celebrated shack in the sand country of Wisconsin. Like many other rivers that eventually won designation as national wild and scenic rivers, the Current was threatened by proposed hydroelectric dams. -

Standard Common and Current Scientific Names for North American Amphibians, Turtles, Reptiles & Crocodilians

STANDARD COMMON AND CURRENT SCIENTIFIC NAMES FOR NORTH AMERICAN AMPHIBIANS, TURTLES, REPTILES & CROCODILIANS Sixth Edition Joseph T. Collins TraVis W. TAGGart The Center for North American Herpetology THE CEN T ER FOR NOR T H AMERI ca N HERPE T OLOGY www.cnah.org Joseph T. Collins, Director The Center for North American Herpetology 1502 Medinah Circle Lawrence, Kansas 66047 (785) 393-4757 Single copies of this publication are available gratis from The Center for North American Herpetology, 1502 Medinah Circle, Lawrence, Kansas 66047 USA; within the United States and Canada, please send a self-addressed 7x10-inch manila envelope with sufficient U.S. first class postage affixed for four ounces. Individuals outside the United States and Canada should contact CNAH via email before requesting a copy. A list of previous editions of this title is printed on the inside back cover. THE CEN T ER FOR NOR T H AMERI ca N HERPE T OLOGY BO A RD OF DIRE ct ORS Joseph T. Collins Suzanne L. Collins Kansas Biological Survey The Center for The University of Kansas North American Herpetology 2021 Constant Avenue 1502 Medinah Circle Lawrence, Kansas 66047 Lawrence, Kansas 66047 Kelly J. Irwin James L. Knight Arkansas Game & Fish South Carolina Commission State Museum 915 East Sevier Street P. O. Box 100107 Benton, Arkansas 72015 Columbia, South Carolina 29202 Walter E. Meshaka, Jr. Robert Powell Section of Zoology Department of Biology State Museum of Pennsylvania Avila University 300 North Street 11901 Wornall Road Harrisburg, Pennsylvania 17120 Kansas City, Missouri 64145 Travis W. Taggart Sternberg Museum of Natural History Fort Hays State University 3000 Sternberg Drive Hays, Kansas 67601 Front cover images of an Eastern Collared Lizard (Crotaphytus collaris) and Cajun Chorus Frog (Pseudacris fouquettei) by Suzanne L. -

Hellbender Population and Habitat Viability Assessment: Final Report

Cover photos courtesy of Jeff Briggler, MO Dept. Conservation. A contribution of the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group. Briggler, J., J. Utrup, C. Davidson, J. Humphries, J. Groves, T. Johnson, J. Ettling, M. Wanner, K. Traylor-Holzer, D. Reed, V. Lindgren, O. Byers (eds.) 2007. Hellbender Population and Habitat Viability Assessment: Final Report. IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group, Apple Valley, MN. IUCN encourage meetings, workshops and other fora for the consideration and analysis of issues related to conservation, and believe that reports of these meetings are most useful when broadly disseminated. The opinions and recommendations expressed in this report reflect the issues discussed and ideas expressed by the participants in the workshop and do not necessarily reflect the formal policies IUCN, its Commissions, its Secretariat or its members. © Copyright CBSG 2007 Additional copies of the Hellbender Population and Habitat Viability Assessment: Final Report can be ordered through the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group, 12101 Johnny Cake Ridge Road, Apple Valley, MN 55124, USA www.cbsg.org. Dedication Ron Goellner, Director of Animal Collections at the Saint Louis Zoo, passed away on 26 February 2006 after a year-long battle with cancer. His career at the Saint Louis Zoo spanned 35 years, starting as a reptile keeper in 1970. Within a few years he was promoted to Curator of Reptiles, a position he held until 1995. For the past 10 years Ron served as Director of Animal Collections for the Zoo, where he oversaw a collection of 11,400 animals, ranging from American burying beetles to Asian elephants. -

Recovery Outline for the Ozark Hellbender

Recovery Outline for the Ozark Hellbender Common Name: Ozark Hellbender Scientific Name: Cryptobranchus alleganiensis bishopi Classification: Endangered Effective Listing Date: November 7, 2011 Recovery Priority Number: 3 Lead Region: Region 3 Cooperating Regions: Region 4 Lead Office: Columbia Missouri Field Office 101 Park DeVille Dr., Suite A Columbia, MO 65203 Phone: 573-234-2132 Photo courtesy of Jeff Briggler Purpose of the Recovery Outline In the interim between listing and recovery plan approval, a recovery outline provides preliminary strategies for conservation that conform to the mandates of the Endangered Species Act (ESA), as amended. It organizes near-term recovery actions, provides a range-wide conservation context for U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) decisions, and sets the stage for recovery planning and stakeholder involvement. Information Sources and Treatment of Uncertainties This recovery outline is based on the best available data, including the Hellbender Conservation Strategy (Briggler et al. 2010), the Spotlight Species Action Plan (USFWS 2009), the listing decision (USFWS 2011, 76 FR 61959), and recent information from species experts. Research needed to address information gaps is described in this document and will be part of the implementation table in the recovery plan. For issues in which there is uncertainty associated with the conservation needs, caution will be exercised until such uncertainty can be resolved. I. RECOVERY STATUS ASSESSMENT A. Species Description and Life History The Ozark Hellbender is a large, strictly aquatic salamander endemic to streams of the Ozark Highlands in southern Missouri and northern Arkansas. They have a large, keeled tail; small eyes; and a dorso-ventrally flattened body that enables movements in the fast- flowing streams it inhabits (Nickerson and Mays 1973). -

A Quantitative Field Study of Paternal Care in Ozark Hellbenders

Journal of Ethology (2018) 36:235–242 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10164-018-0553-0 ARTICLE A quantitative feld study of paternal care in Ozark hellbenders, North America’s giant salamanders Rachel A. Settle1 · Jefrey T. Briggler2 · Alicia Mathis1 Received: 14 December 2017 / Accepted: 22 June 2018 / Published online: 11 July 2018 © Japan Ethological Society and Springer Japan KK, part of Springer Nature 2018 Abstract Paternal care is relatively uncommon in tetrapods but appears to be the rule in the large aquatic salamanders of the primitive family Cryptobranchidae (North America: hellbenders, genus Cryptobranchus; Asia: giant salamanders, genus Andrias). For the Ozark hellbender, C. alleganiensis bishopi, a federally endangered subspecies, anecdotal observations of paternal care have been reported, but no quantitative assessments have been made. We quantifed behavior of a guarding male hellbender from video footage collected over 6 weeks in 2008 from a naturally occurring nest. We quantifed behavior of the guarding male to help develop hypotheses about costs and benefts of paternal care. Overall, there were high frequencies of tail fan- ning of the eggs and rocking behaviors (rhythmic, lateral back-and-forth movements of the body), which increase aeration of the nest. The male rarely left the nest unguarded and spent over half of the recorded time at the nest exposed at the nest entrance. Potential egg predators observed included centrarchid, cyprinid, ictalurid, and percid fshes, with centrarchids being the most common and exhibiting the most interest in the nest. The frequency of foraging by the male was low (n = 8 strikes at identifable prey), with a 37% success rate. -

SERDP Project ER18-1653

FINAL REPORT Approach for Assessing PFAS Risk to Threatened and Endangered Species SERDP Project ER18-1653 MARCH 2020 Craig Divine, Ph.D. Jean Zodrow, Ph.D. Meredith Frenchmeyer Katie Dally Erin Osborn, Ph.D. Paul Anderson, Ph.D. Arcadis US Inc. Distribution Statement A Page Intentionally Left Blank This report was prepared under contract to the Department of Defense Strategic Environmental Research and Development Program (SERDP). The publication of this report does not indicate endorsement by the Department of Defense, nor should the contents be construed as reflecting the official policy or position of the Department of Defense. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the Department of Defense. Page Intentionally Left Blank Form Approved REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE OMB No. 0704-0188 The public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing the burden, to Department of Defense, Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports (0704-0188), 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302. Respondents should be aware that notwithstanding any other provision of law, no person shall be subject to any penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information if it does not display a currently valid OMB control number. -

Ozark Hellbender Biological Report

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Biological Report for the Ozark Hellbender (Cryptobranchus alleganiensis bishopi) Ozark Hellbender; Photo: Jeffrey Briggler, Missouri Department of Conservation Version 1.0 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Missouri Ecological Services Field Office Columbia, Missouri March 2, 2020 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report was prepared by Trisha Crabill (Missouri Ecological Services Field Office) with assistance from Laura Ragan (Midwest Regional Office). We greatly appreciate the following individuals who provided information on the current status and threats of the Ozark hellbender: Dr. Jeffrey Briggler (Missouri Department of Conservation), Kelly Irwin (Arkansas Game and Fish Commission), Lauren Augustine (Saint Louis Zoo), Dr. Jeffery Ettling (Sedgwick County Zoo; previously Saint Louis Zoo), Mark Wanner (Saint Louis Zoo), Chris Davidson (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service), Theresa Davidson (Mark Twain National Forest), Victoria Grant (Ozark National Scenic Riverways), and Alyssa Bangs (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service). Suggested citation: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2020. Biological report for the Ozark hellbender (Cryptobranchus alleganiensis bishopi). Version 1.0, March 2, 2020. Midwest Region, Bloomington, Minnesota. 81 pp. ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Ozark hellbender (Cryptobranchus alleganiensis bishopi) is a large aquatic salamander inhabiting cool, fast-flowing streams and rivers in the Ozark Highlands of southern Missouri and northern Arkansas. As a result of drastic population declines, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) listed the Ozark hellbender in October 2011 as endangered under the Endangered Species Act of 1973, as amended (Act). This report summarizes the biology of the Ozark hellbender and provides a scientific assessment of the species’ status and viability, including those factors that impact or are likely to impact the species. -

Augustine Et Al 2016

Publisher of Journal of Herpetology, Herpetological Review, Herpetological Circulars, Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles, and three series of books, Facsimile Reprints in Herpetology, Contributions to Herpetology, and Herpetological Conservation Officers and Editors for 2015-2016 President AARON BAUER Department of Biology Villanova University Villanova, PA 19085, USA President-Elect RICK SHINE School of Biological Sciences University of Sydney Sydney, AUSTRALIA Secretary MARION PREEST Keck Science Department The Claremont Colleges Claremont, CA 91711, USA Treasurer ANN PATERSON Department of Natural Science Williams Baptist College Walnut Ridge, AR 72476, USA Publications Secretary BRECK BARTHOLOMEW Notice warning concerning copyright restrictions P.O. Box 58517 Salt Lake City, UT 84158, USA Immediate Past-President ROBERT ALDRIDGE Saint Louis University St Louis, MO 63013, USA Directors (Class and Category) ROBIN ANDREWS (2018 R) Virginia Polytechnic and State University, USA FRANK BURBRINK (2016 R) College of Staten Island, USA ALISON CREE (2016 Non-US) University of Otago, NEW ZEALAND TONY GAMBLE (2018 Mem. at-Large) University of Minnesota, USA LISA HAZARD (2016 R) Montclair State University, USA KIM LOVICH (2018 Cons) San Diego Zoo Global, USA EMILY TAYLOR (2018 R) California Polytechnic State University, USA GREGORY WATKINS-COLWELL (2016 R) Yale Peabody Mus. of Nat. Hist., USA Trustee GEORGE PISANI University of Kansas, USA Journal of Herpetology PAUL BARTELT, Co-Editor Waldorf College Forest City, IA 50436, USA TIFFANY -

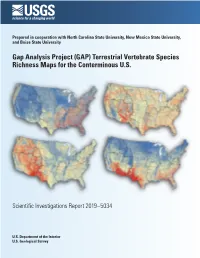

Gap Analysis Project (GAP) Terrestrial Vertebrate Species Richness Maps for the Conterminous U.S

Prepared in cooperation with North Carolina State University, New Mexico State University, and Boise State University Gap Analysis Project (GAP) Terrestrial Vertebrate Species Richness Maps for the Conterminous U.S. Scientific Investigations Report 2019–5034 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover. Mosaic of amphibian, bird, mammal, and reptile species richness maps derived from species’ habitat distribution models of the conterminous United States. Gap Analysis Project (GAP) Terrestrial Vertebrate Species Richness Maps for the Conterminous U.S. By Kevin J. Gergely, Kenneth G. Boykin, Alexa J. McKerrow, Matthew J. Rubino, Nathan M. Tarr, and Steven G. Williams Prepared in cooperation with North Carolina State University, New Mexico State University, and Boise State University Scientific Investigations Report 2019–5034 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior DAVID BERNHARDT, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey James F. Reilly II, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2019 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit https://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS (1–888–275–8747). For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit https://store.usgs.gov. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this information product, for the most part, is in the public domain, it also may contain copyrighted materials as noted in the text. -

North America's Giant Salamander

FNR-536-W HELP THE HELLBENDER North America’s Giant Salamander Nicholas G. Burgmeier Shem D. Unger Brianna Osinski Rod N. Williams Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources WHAT IS A HELLBENDER? The eastern hellbender (Cryptobranchus alleganiensis alleganiensis) is a large, fully aquatic salamander that requires cool, well-oxygenated rivers and streams. Because they require high-quality water and habitat, they are thought to be indicators of healthy stream ecosystems. While individuals may live up to 29 years, possibly longer, many populations of this unique salamander are in decline across their geographic range. Common Nicknames Snot otter Water dog Devil dog Allegheny alligator Water eel Grampus Old lasagna sides Cover photo by T. Travis Brown Photos by the authors, unless otherwise noted. 1 What’s in a Name? What's in a Name? Hidden below (hidden much like our shy hellbender friends) are some of the different names used to refer to hellbenders.Hidden Whatever below you (callhidden them, m oneuch fact li kerings our true, shy they hellbender are one spectacular friends) asalamander!re some of the different names used to refer to hellbenders. Whatever you call them, one fact rings true, they are one spectacular salamander! B S G M U D D O G A B S Z S Q X H A O T W N T L E U J U T V T T E J D V A L U P K H C W P S K D L R L I W M N C D Q E A U G K R L G I A A N R P P E L O W Y J A B R V A Y S N L G L H S E T T G E R E B U F C W E S H O F H C B N P D L J Z T G N R T G R O U N D P U P P Y H A L U I T I X C U E Z E X N A S O J P E C K F N N R B L B N O H Y R E T T O T O N S Y M Y I R V Q A H H F F X W F F D W C M C Y K J E T G L J B V E X L R W K O X A W N Z V I T B Y ALLEGHANY GRAMPUS OSANSHOU* ALLIGATOR GROUNDPUPPY SNOTOTTER CRYPTOBRANCHUS HELLBENDER TWEEG** DEVILDOG MUDDOG WAWAYU*** *Japanese Giant Salamander **Native American term for “Hellbender” ***Chinese Giant Salamander Quick Facts The hellbender is one of the largest North American salamanders (up to 29 inches), and is the sixth Quick Facts largest in the world. -

FOREST REMOVAL and the CASCADE of EFFECTS CORRESPONDING with an OZARK HELLBENDER POPULATION DECLINE Max A.Nickerson1, Amber L

FOREST REMOVAL AND THE CASCADE OF EFFECTS CORRESPONDING WITH AN OZARK HELLBENDER POPULATION DECLINE Max A.Nickerson1, Amber L. Pitt2, Joseph J. Tavano3, Kirsten A. Hecht4, and Joseph C. Mitchell1 ABSTRACT Populations of the endangered Ozark Hellbender salamander (Cryptobranchus alleganiensis bishopi) in the North Fork of the White River (NFWR) in Missouri and other streams have declined precipitously in recent decades. Deforestation of the riparian and nearby upland habitat has corresponded with in-river habitat changes and other interacting stressors that coincide chronologically with the precipitous decline. We review the cascade of effects, including changes in water quality, benthic habitat, illegal and scientific harvesting, and introduced and reintroduced species occurrence that followed deforestation in the context of their impacts on hellbenders and relationship with other stressors such as climate change. In-river habitat changes since the 1960s include benthic microhabitat alterations associated with redistribution of gravel, siltation, and sedimentation and, in part, increases in nuisance vegetation, including periphyton. Deforestation of riparian and nearby upland habitats increased access and opportunities for human activities such as recreation, wildlife collection, and development. The subsequent degradation of stream habitat and water quality following deforestation reduced the carrying capacity for the NFWR Ozark Hellbender population and had negative consequences on population health. Key words: conservation, Cryptobranchus alleganiensis bishopi, deforestation, Ozark Hellbender, sala- manders, sedimentation, river. Published On-line: January 20, 2017 Open Access Download at https://www.flmnh.ufl.edu/bulletin/publications/ ISSN 2373-9991 Copyright © 2017 by the Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida. All rights reserved. Text, images and other media are for nonprofit, educational, or personal use of students, scholars, and the public. -

Conservation Assessment for Ozark Hellbender (Cryptobranchus Alleganiensis Bishopi Grobman)

Conservation Assessment for Ozark hellbender (Cryptobranchus alleganiensis bishopi Grobman) Female on the left (bigger) and male on the right (smaller). Photo credit: Dr. Yue-wern Huang USDA Forest Service, Eastern Region Information compiled by Larry L. Furniss 9/25/2003 Mark Twain National Forest 401 Fairgrounds Road Rolla, MO 65401 This document is undergoing peer review, comments welcome. CONTRIBUTING AUTHORS Jeff Briggler Missouri Department of Conservation [email protected] Susan Rogers U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service [email protected] Larry Furniss U.S. Forest Service [email protected] Yue-wern Huang University of Missouri- Rolla [email protected] Alicia Mathis Southwest Missouri State University [email protected] Stan Trauth Arkansas State University [email protected] Ben Wheeler Arkansas State University [email protected] This Conservation Assessment was prepared to compile the published and unpublished information on Cryptobranchus alleganiensis bishopi Grobman. It does not represent a management decision by the U.S. Forest Service. Though the best scientific information available was used and subject experts were consulted in preparation of this document, it is expected that new information will arise. In the spirit of continuous learning and adaptive management, if you have information that will assist in conserving the subject community and associated taxa, please contact the Eastern Region of the Forest Service - Threatened and Endangered Species Program at 310 Wisconsin Avenue, Suite 580 Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Table