Compounding Injustice: India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"Demons Within"

Demons Within the systematic practice of torture by inDian police a report by organization for minorities of inDia NOVEMBER 2011 Demons within: The Systematic Practice of Torture by Indian Police a report by Organization for Minorities of India researched and written by Bhajan Singh Bhinder & Patrick J. Nevers www.ofmi.org Published 2011 by Sovereign Star Publishing, Inc. Copyright © 2011 by Organization for Minorities of India. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, digital, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise or conveyed via the internet or a web site without prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Inquiries should be addressed to: Sovereign Star Publishing, Inc PO Box 392 Lathrop, CA 95330 United States of America www.sovstar.com ISBN 978-0-9814992-6-0; 0-9814992-6-0 Contents ~ Introduction: India’s Climate of Impunity 1 1. Why Indian Citizens Fear the Police 5 2. 1975-2010: Origins of Police Torture 13 3. Methodology of Police Torture 19 4. For Fun and Profit: Torturing Known Innocents 29 Conclusion: Delhi Incentivizes Atrocities 37 Rank Structure of Indian Police 43 Map of Custodial Deaths by State, 2008-2011 45 Glossary 47 Citations 51 Organization for Minorities of India • 1 Introduction: India’s Climate of Impunity Impunity for police On October 20, 2011, in a statement celebrating the Hindu festival of Diwali, the Vatican pled for Indians from Hindu and Christian communities to work together in promoting religious freedom. -

Concerned Citizens Tribunal - Gujarat 2002 an Inquiry Into the Carnage in Gujarat

Concerned Citizens Tribunal - Gujarat 2002 An inquiry into the carnage in Gujarat Hate Speech The carnage in Gujarat was marked by unprecedented levels of hate speech and hate propaganda. Some examples: Chief Minister Narendra Modi Terming the (Godhra) attack as ‘pre-planned, violent act of terrorism’, Mr Modi said that state government was viewing this attack seriously. — The Times of India, Feb 28, 2002. "With the entire population of Gujarat very angry at what happened in Godhra much worse was expected". — Narendra Modi, at a Press Conference in Gujarat, Feb 28, 2002. Modi said he was ‘absolutely satisfied’ with the way in which the police and State Government handled the backlash from Godhra incident and ‘happy’ that violence was largely contained… "We should be happy that curfew has been imposed only at 26 places while there is anger and people are burning with revenge. Thanks to security arrangements we brought things under control".When asked that not a policeman was visible in most areas where shops were looted and set on fire, he said he hadn’t received any complaint. — The Indian Express, March 1, 2002. "Investigations have revealed that the firing by the Congressman played a pivotal role in inciting the mob." — CM Narendra Modi on Chamanpura incident where former MP Ahsan Jaffri was burned alive with 19 of his relatives. On being asked what could have lead to the Ex-MP opening fire it was ‘probably in his nature’ to do so. — The Hindustan Times, March 2, 2002. Gujarat Chief Minister Narendra Modi on Friday termed ‘barbaric’ the murder of former Congress MP Ehsan Jafri along with 19 of his family members, but said there was firing from inside the house. -

Compounding Injustice: India

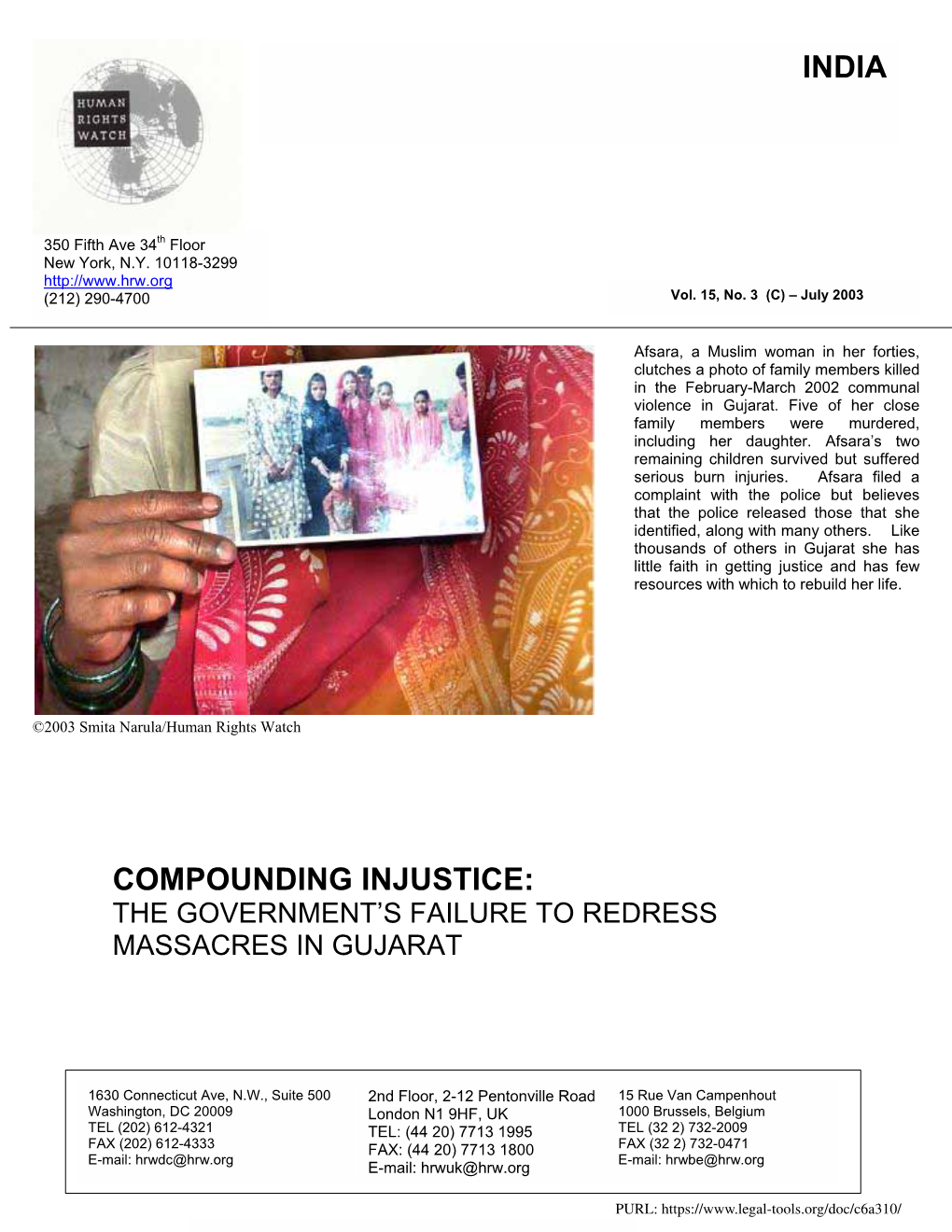

INDIA 350 Fifth Ave 34 th Floor New York, N.Y. 10118-3299 http://www.hrw.org (212) 290-4700 Vol. 15, No. 3 (C) – July 2003 Afsara, a Muslim woman in her forties, clutches a photo of family members killed in the February-March 2002 communal violence in Gujarat. Five of her close family members were murdered, including her daughter. Afsara’s two remaining children survived but suffered serious burn injuries. Afsara filed a complaint with the police but believes that the police released those that she identified, along with many others. Like thousands of others in Gujarat she has little faith in getting justice and has few resources with which to rebuild her life. ©2003 Smita Narula/Human Rights Watch COMPOUNDING INJUSTICE: THE GOVERNMENT’S FAILURE TO REDRESS MASSACRES IN GUJARAT 1630 Connecticut Ave, N.W., Suite 500 2nd Floor, 2-12 Pentonville Road 15 Rue Van Campenhout Washington, DC 20009 London N1 9HF, UK 1000 Brussels, Belgium TEL (202) 612-4321 TEL: (44 20) 7713 1995 TEL (32 2) 732-2009 FAX (202) 612-4333 FAX: (44 20) 7713 1800 FAX (32 2) 732-0471 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] July 2003 Vol. 15, No. 3 (C) COMPOUNDING INJUSTICE: The Government's Failure to Redress Massacres in Gujarat Table of Contents I. Summary............................................................................................................................................................. 4 Impunity for Attacks Against Muslims............................................................................................................... -

Three Years Later, When Cell Phones Ring

Best Breaking News THREE YEARS LATER, WHEN CELL PHONES RING Who spoke to whom, when Gujarat was burning Two CDs with more than 5 lakh entries have been lying with the Gujarat ** Using cellphone tower locations, the data also gives information on the police and are now with the Nanavati-Shah riots panel. These have records physical location of the caller and the person at the other end. of all cellphone calls made in Ahmedabad over the first five days of the riots which saw the worst massacres. PART ONE Two compact discs could change that. For, they contain records of all Tracking VHP’s gen secy on day 1,2 (published 21 November 2004) cellphone calls made in Ahmedabad from February 25, 2002, two days Vishwa Hindu Parishad’s General Secretary in Gujarat is a pathologist called before the horrific Sabarmati Express attack to March 4, five days that saw Jaideep Patel. He was booked for rioting and arson in the Naroda Patiya the worst communal violence in recent history. massacre, the worst post-Godhra riot incident in which 83 were killed, many of them burnt alive. The police closed the case saying there was not This staggering amount of data - there are more than 5 lakh entries - was enough evidence. Records show that Patel, who lives in Naroda, was there investigated over several weeks by this newspaper. They show that Patel when the massacre began, then left for Bapunagar which also witnessed was in touch with the key riot accused, top police officers, including the killings and returned to Naroda. -

Breathing Life Into the Constitution

Breathing Life into the Constitution Human Rights Lawyering In India Arvind Narrain | Saumya Uma Alternative Law Forum Bengaluru Breathing Life into the Constitution Human Rights Lawyering In India Arvind Narrain | Saumya Uma Alternative Law Forum Bengaluru Breathing Life into the Constitution Human Rights Lawyering in India Arvind Narrain | Saumya Uma Edition: January 2017 Published by: Alternative Law Forum 122/4 Infantry Road, Bengaluru - 560001. Karnataka, India. Design by: Vinay C About the Authors: Arvind Narrain is a founding member of the Alternative Law Forum in Bangalore, a collective of lawyers who work on a critical practise of law. He has worked on human rights issues including mass crimes, communal conflict, LGBT rights and human rights history. Saumya Uma has 22 years’ experience as a lawyer, law researcher, writer, campaigner, trainer and activist on gender, law and human rights. Cover page images copied from multiple news articles. All copyrights acknowledged. Any part of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted as necessary. The authors only assert the right to be identified wtih the reproduced version. “I am not a religious person but the only sin I believe in is the sin of cynicism.” Parvez Imroz, Jammu and Kashmir Civil Society Coalition (JKCSS), on being told that nothing would change with respect to the human rights situation in Kashmir Dedication This book is dedicated to remembering the courageous work of human rights lawyers, Jalil Andrabi (1954-1996), Shahid Azmi (1977-2010), K. Balagopal (1952-2009), K.G. Kannabiran (1929-2010), Gobinda Mukhoty (1927-1995), T. Purushotham – (killed in 2000), Japa Lakshma Reddy (killed in 1992), P.A. -

Gujrat Pogrom – a Flagrant Violation of Human Rights and Reflection of Hindu Chauvinism in the Indian Society

Gujrat Pogrom – A Flagrant Violation of Human Rights and Reflection of Hindu Chauvinism in the Indian Society The Incident: Five and half years ago, during the last week of February 2007, the Muslims living across the Indian state of Gujarat witnessed their massacre at the hands of their Hindu compatriots. On 27 February, the stormtroopers of the Hindu right, decked in saffron sashes and armed with swords, tridents, sledgehammers and liquid gas cylinders, launched a pogrom against the local Muslim population. They looted and torched Muslim-owned businesses, assaulted and murdered Muslims, and gang-raped and mutilated Muslim women. By the time the violence spluttered to a halt, about 2,500 Muslims had been killed and about 200,000 driven from their homes. The Gujrat pogrom, which has been documented through recent interviews of perpetrators of the pogrom, was distinguished not only by its ferocity and sadism (foetuses were ripped from the bellies of pregnant women, old men bludgeoned to death) but also by its meticulous advance planning with the full support of government apparatus. The leaders used mobile phones to coordinate the movement of an army of thousands through densely populated areas, targeting Muslim properties with the aid of computerized lists and electoral rolls provided by state agencies. It has been established by independent reports that the savagery of the anti-Muslim violence was planned, coordinated and implemented with the complicity of the police and the state government. The Gujarat carnage was unprecedented in the history of communal riots in India. Never such communal violence took place with so much active collaboration of the state. -

The Ecology of Ethnic Violence: Attacks on Muslims of Ahmedabad in 2002

Qual Sociol (2016) 39:71–95 DOI 10.1007/s11133-015-9320-5 The Ecology of Ethnic Violence: Attacks on Muslims of Ahmedabad in 2002 Raheel Dhattiwala 1 Published online: 28 December 2015 # Springer Science+Business Media New York 2015 Abstract Ethnic violence killed at least a thousand Muslims in Gujarat (western India) in 2002. The role of political elites in orchestrating attacks against Muslims for electoral gains was a conspicuous characteristic of the violence. Yet, as this article demonstrates, the political thesis was insufficient in explaining why neighborhoods, often contiguous, experienced different levels of violence. Alternative explanations, such as interethnic contact, were also found wanting. A unique research design allowing the comparison of neighborhoods in the same electoral ward in the city of Ahmedabad demonstrates the critical role of ecology in explaining microspatial variation in the violence. Even when attacks were politically orches- trated, attackers still acted with some regard to self-preservation in selecting which location to attack. Observational and testimonial evidence based on 22 months of ethnographic fieldwork reveals the importance of two ecological factors: the built environment and the population distribution of potential targets. Together, the two factors heavily shaped crowds’ decisions to attack or escape, thus influencing the subsequent success or failure of the attack. Muslims were most vulnerable where they were concentrated in small numbers and on routes that afforded the attackers obstacle-free entry and retreat. Where the potential targets had an obstacle-free escape route to a large concentration of fellow Muslims, the outcome was looting and arson rather than killing. By implication, the course of politically orchestrated violence was com- plicated by the ecology of the targeted space. -

Müller Indien Ganz Rechts 2014 04 29

1 DEUTSCHLANDFUNK Sendung: Hörspiel/Hintergrund Kultur Dienstag, 29.04.2014 Redaktion: Karin Beindorff 19.15 – 20.00 Uhr Indien ganz rechts Die Karriere des Hindunationalisten Narendra Modi Von Dominik Müller URHEBERRECHTLICHER HINWEIS Dieses Manuskript ist urheberrechtlich geschützt und darf vom Empfänger ausschließlich zu rein privaten Zwecken genutzt werden. Jede Vervielfältigung, Verbreitung oder sonstige Nutzung, die über den in §§ 45 bis 63 Urheberrechtsgesetz geregelten Umfang hinausgeht, ist unzulässig. Deutschlandradio - Unkorrigiertes Manuskript - 1 2 O-Ton Anand Sharma, Wirtschaftsminister Would you insult at hundreds of million of voters in India? .... Respect democracy, respect our country! Sprecher 1 Würden Sie hunderte Millionen Wähler in Indien beleidigen? Würden Sie ihnen vorschreiben, wie sie zu entscheiden haben? Schreiben wir anderen Ländern vor, wie ihre Wähler abstimmen sollen? Respektieren Sie die Demokratie, respektieren Sie unser Land! Atmo Nachrichten CNN-IBN Erzähler Anand Sharma, der amtierende indische Wirtschaftsminister, ärgerte sich, als die US-Bank Goldman Sachs Anfang November 2013 eine Prognose über die Entwicklung der Wirtschaft in Indien veröffentlichte. Schon der Titel „Modi-fying our view“ war eine wenig subtile Wahlempfehlung für den Spitzenkandidaten der größten Oppositionspartei: Narendra Modi von der BJP, der Bharatiya Janata Party, der Indischen Volkspartei. Die mächtige US-Bank machte Stimmung: Sprecher: (Modi ist) ein Agent des Wandels, der Indien von einem Leichtgewicht zu einem Marktschwergewicht -

NCM File No. MIDL/30/0036/12 COMPLAINT of MALEK NIYAZBIBI BANNUMIYAN Dated 10

BEFORE THE NATIONAL COMMISSION FOR MINORITIES, NEW DELHI Re: NCM File No. MIDL/30/0036/12 COMPLAINT OF MALEK NIYAZBIBI BANNUMIYAN dated 10. AFFIDAVIT OF SANJIV RAJENDRA BHATT I, SANJIV RAJENDRA BHAlT, aged about 48 years residing at:, Bungalow No.2, Sushil Nagar Part 11, Opposite Mahatma Gandhi Labour ': Institute, Drive-in Road, Ahmedabad 380 052, do hereby state and ',: solemnly affirm as under: 1. Iam filing this affidavit in furtherance of my earlier affidavit dated April 25, 2012, through which Ihadinter alia sought to bring out certain facts regarding the inadequacies of the investigation carried out by the SIT into the Complaintdated June 08, 2006,made by Mrs.ZakiaJafri pertaining tovarious allegations regarding the larger conspiracy and orchestration behind the Gujarat Riots of 2002. The Complaint of Mrs.ZakiaJafri encompasses the abominable and woeful events which took place inthe State of Gujarat between 'Mbruary, 2002 and May, ZOO2 after the abhorrent Godhra incident on 27th February, 2002.My earlier affidavit sought to bring out certain details regarding the dubious role of the State Government of Gujarat in shielding the high and mighty including the Chief Minister Mr.NarendraModi from lawful inquisition and legal punishment.1 had also averred in my earlier affidavit, that the Honourable Justice Nanavati and Mehta- Commission of Inquiry and the SIT were deliberately turning a blind eye to the overwhelming ddtumentary, oral and circumstantial evidence to conceal the complicity of the State Government of Gujarat and its high functionaries in the Gujarat Carnage of 2002. 2. I have now had the occasion to peruse the Report submitted by SIT in compliance of the order passed by the Honourable Supreme Court on September 12, 2011 in Criminal Appeal No. -

Mrs. Zakia Ahsan Jafri V/S Mr

IN THE COURT OF THE 11th METROPOLITAN MAGISTRATE, AHMEDABAD MRS. ZAKIA AHSAN JAFRI V/S MR. NARENDRA MODI & OTHERS PROTEST PETITION ON THE COMPLAINT DATED 8.6.2006 & AGAINST THE FINAL REPORT OF THE SPECIAL INVESTIGATION TEAM DATED 8.2.2012 (PART I) 1 MAIN INDEX TO PROTEST PETITION Sr.No. Subject Page Nos Opening Page of the Protest Petition Filed on 15.4.2013 1. Main Petition:- PART I 2. Main Petition:- PART II Main Petition Continues PLUS Compilation of Supreme Court Orders in SLP1088/2008 & SLP 8989/2013 Graphic Depicting Distances from Sola Civil Hospital to the Sola Civil Police Station, Commissioner of Police, Ahmedabad’s Office, Airport, Two Crematoriums at Hatkeshwar near Ramol and Gota; Naroda & Gulberg Chart of PCR (Police Control Room Messages) Showing Aggressive Mobilisation at the Sola Civil Hospital Chart of SIB Messages recording the arrival of the Sabarmati Express from Godhra at the Ahmedabad Railway station at Kalupur on 27.2.2002 & Murderous Sloganeering by the VHP and Others Map showing Gujarat-wide Mobilisation through aggressive Funeral Processions on 27.2.2002, 28.2.2002 & 1.3.2992 onwards & attacks on Minorities Map showing Scale of Violence all over Gujarat in 2002 Map showing Details of Deaths, Missing Person, Destruction on Homes, Shrines in 2002 3. ANNEXURES -VOLUME I (Sr Nos 1- 51) 1 – 304 pages News reports related to Provocations, Sandesh Articles, SIB Statistics, Important Letters from SIB, Rahul Sharma, Statistics on Police Firing & Tables Extracted from the SIB Messages/PCR messages from the SIT Papers, VHP Pamphlets & Petitioners Letters to Investigating agency 1 – 162 pages 4. -

Centre Bifurcates J&K Into 2

Follow us on: RNI No. TELENG/2018/76469 @TheDailyPioneer facebook.com/dailypioneer Established 1864 Published From ANALYSIS 9 HYDERABAD 11 SPORTS 16 HYDERABAD DELHI LUCKNOW DNA DATABASE TAX A DEADLIER AUSSIES DOWN ENGLAND BHOPAL RAIPUR CHANDIGARH AND FORENSICS TERROR FOR ENTREPRENEURS IN ASHES OPENER RANCHI BHUBANESWAR DEHRADUN VIJAYAWADA *LATE CITY VOL. 1 ISSUE 303 HYDERABAD, TUESDAY AUGUST 6, 2019; PAGES 16 `3 *Air Surcharge Extra if Applicable BELLAMKONDA SURESH TO LAUNCH HIS SON IN B’WOOD { Page 13 } www.dailypioneer.com NARENDRA MODI FULFILS HIS PROMISE TO THE NATION ARTICLE 370 REVOKED SCRAPPING BEFORE NOW Centre bifurcates J&K into 2 UTs Special powers No special exercised by J&K powers now PNS n NEW DELHI Dual citizenship Single citizenship The government on Monday Separate flag for Tricolour will be the revoked Article 370 which Jammu & Kashmir only flag gave special status to Jammu and Kashmir and proposed Article 360 (Financial Emergency) Article 360 that the state be bifurcated into not applicable applicable two union territories, Jammu No reservation for minorities Minorites will be eligible and Kashmir and Ladakh, such as Hindus and Sikhs for 16% reservation provoking outrage from the NC and PDP and triumph Indian citizens from other People from other States from leaders of India's rul- States cannot buy land or will now be able to purchase ing BJP. Meeting a long-held property in J&K land or property in J&K promise of the BJP, Union RTI not applicable RTI will be applicable Home Minister Amit Shah The president on the recommendation moved a resolution in the Duration of Legislative Assembly duration in Union of Parliament is pleased to declare as Assembly for 6 years Territory of J&K will be for Rajya Sabha that Article 370, which allowed Jammu of 5th of August 2019, all clauses of the 5 years and Kashmir to have its own said Article 370 shall cease to be If a woman from J&K marries If a woman from J&K Constitution, will no longer be operative.. -

Master Thesis Moland Hansen.Pdf (509.4Kb)

Identity, Votes and Violence Degree of Hindu-Muslim Conflict in Gujarat and Rajasthan Katrine Moland Hansen Master Thesis Department of Comparative Politics University of Bergen June 2008 Identity, Votes and Violence Degree of Hindu-Muslim Conflict in Gujarat and Rajasthan Katrine Moland Hansen Master Thesis Department of Comparative Politics University of Bergen June 2008 It has always been a mystery to me how men can feel themselves honoured by the humiliation of their fellow beings Mahatma Gandhi* Abstract The thesis explores variation in the degree of Hindu-Muslim conflict in the Indian states Gujarat and Rajasthan. Gujarat is characterised by Hindu-Muslim political conflict as well as endemic religious violence. In 2002 more than 2000 people, predominantly Muslims were killed in religious violence. The State Government, the Police and the Judiciary have displayed pro-Hindu and anti-Muslim sympathies. The government of Rajasthan is generally not perceived as biased, nor has the state experienced widespread religious violence. The religious conflict is manifest through party politics and the degree of conflict is moderate. The analysis of Hindu-Muslim conflict is two-fold. First, the states are compared in terms of degree of Hindu-Muslim polarisation in conventional politics. Cleavage theory is utilised to explore the relationship between crosscutting and overlapping cleavages and Hindu-Muslim polarisation. The role of actors in constructing religious identities and thereby influencing the degree of religious polarisation will be explored through a constructivist approach to identity. Second, states are compared in terms of violence, judicial and government bias. The role of elites in preparing, enacting and explaining violence is explored through an instrumentalist approach to violence, and the relationship between electoral incentives and Hindu-Muslim violence will also be discussed.