Coping with Injustice with Coping

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rptmanageenginner

Structural Engineer Details Reg. No. Name Type Resident Address Office Address Mobile No. Reg. Date Validity Date Email ID SD-1/089 Ruwala Kautuk Structural b 408, emerald 403, onyx, nr 9825014690 30-Mar-2017 29-Mar-2022 [email protected] Pradipbhai Engineer residency, nr punjabi hall, rajhans society, navrangpura, gulbai tekra, SD-I/002 Vagadia Virendra Structural 25, Vishvakarma 23, Avani Complex, 9825466860 15-Dec-2018 14-Dec-2023 [email protected] Chandulal Engineer Society,Jivrajpark, Navrangpura, Ahmedabad 380051 Ahmedabad 380009 SD-I/00305 MAHENDRA M Structural 142, HANUMAN FALIYA, 142, HANUMAN 9824144249 12-Aug-2015 11-Aug-2020 [email protected] MISTRY Engineer NR. DABHOLI GARDEN, FALIYA, NR. DABHOLI, SURAT- DABHOLI SD-I/00306 ASHWIN Structural as above 1/6 MARUTINAGAR 9824210151 23-Sep-2015 22-Sep-2020 [email protected] MANILAL Engineer AIRPORT ROAD LODHIYA RAJKOT 36001 SD-I/00307 Himanshu Structural SAKAAR, RSC-4, SAKAAR, RSC-4, 9821111493 28-Sep-2015 27-Sep-2020 [email protected] Madhukar Raje Engineer 391/217A, NEAR BEST 391/217A, NEAR QTRS, SECTOR 1, BEST QTRS, SD-I/00308 Katariya Structural as above 12, Trilok row 9898989577 26-Oct-2015 25-Oct-2020 [email protected] Maheshkumar Engineer house, Opp. Trilok Madhubhai Bunglows, SD-I/00309 GAJJAR Structural A-401, ARJUN A-401, ARJUN 9825625461 12-Jan-2016 11-Jan-2021 [email protected] KRUSHNAKANT Engineer ELEGANCE, OPP. ELEGANCE, OPP. ARVINDKUMAR BHAGIRATH SOCIRTY, BHAGIRATH SD-I/00310 PATEL Structural 19, UMIYANAGAR 19, UMIYANAGAR 8401762260 -

"Demons Within"

Demons Within the systematic practice of torture by inDian police a report by organization for minorities of inDia NOVEMBER 2011 Demons within: The Systematic Practice of Torture by Indian Police a report by Organization for Minorities of India researched and written by Bhajan Singh Bhinder & Patrick J. Nevers www.ofmi.org Published 2011 by Sovereign Star Publishing, Inc. Copyright © 2011 by Organization for Minorities of India. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, digital, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise or conveyed via the internet or a web site without prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Inquiries should be addressed to: Sovereign Star Publishing, Inc PO Box 392 Lathrop, CA 95330 United States of America www.sovstar.com ISBN 978-0-9814992-6-0; 0-9814992-6-0 Contents ~ Introduction: India’s Climate of Impunity 1 1. Why Indian Citizens Fear the Police 5 2. 1975-2010: Origins of Police Torture 13 3. Methodology of Police Torture 19 4. For Fun and Profit: Torturing Known Innocents 29 Conclusion: Delhi Incentivizes Atrocities 37 Rank Structure of Indian Police 43 Map of Custodial Deaths by State, 2008-2011 45 Glossary 47 Citations 51 Organization for Minorities of India • 1 Introduction: India’s Climate of Impunity Impunity for police On October 20, 2011, in a statement celebrating the Hindu festival of Diwali, the Vatican pled for Indians from Hindu and Christian communities to work together in promoting religious freedom. -

Charge Sheet

1 CHARGE SHEET Police station Naroda Dist Ahmedabad Charge sheet No 295/08 Date 11.12.08 Name, address & occupation of complainant / informer Shri VK Solanki Service Naroda police station Ahmedabad city. First information report no I CR No 100/02 / Date 28-2-02. Name address of Name address of Property (including Name and address of Charge or accused sent for trial accused not sent up weapons) found with witness. information name in custody on bail. for trial whether particulars of where, of offence & address and not when by & by whom circumstance addressed found & whether connected with it, including forwarded to Magistrate. in concise detail & absconders under what section (show absconder in of law charged. red ink). 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 1. Ashok Died Accused: --------- Nil-------- 1.Complainant him Offence : u/s Uttamchand Korani 1. Gulabbhai self. 143,147,148,149, (Sindhi), Age 43 Kalubhai Vanjhara, 2. Complainant Shri 302,332,323,395, years, Re. Janta Age 19 years, Re. Mahemudbhai 396, 397,398, 435, Nagar Society, Nr. Krushnanagar, Abbasbhai Bagdadi 436, 427, 376, 120 Apnaghar Society, Bhagirath resi at Chetandas’s B, 186,188, 153(A) 2 Naroda Bungalo’s, chali beside ST (1) (A) (B) and part 2. Vijaykumar Thakkarnagar, workshop Naroda 2 of 153 (A) (1) of Takhubhai Parmar, Naroda Patiya, Ahmedabad. IPC and U/s 135 (1) Age. 25 years, Ahmedabad, died in (Naroda I 111/02). of BP Act, in such Re.Mahajaniyawas, police firing in mob 3. Complainant Shri a way that, as the Jatubhai Chapra, at Naroda Patiya. Sumarmiyan incident of burning Saijpur Patiya, Muhammadmiyan alive 58 (Hindu) Naroda 2. -

87 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

87 bus time schedule & line map 87 Kalupur Terminus - Chandkheda View In Website Mode The 87 bus line (Kalupur Terminus - Chandkheda) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Chandkheda: 6:40 AM - 9:30 PM (2) Kalupur Terminus: 7:50 AM - 10:40 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 87 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 87 bus arriving. Direction: Chandkheda 87 bus Time Schedule 26 stops Chandkheda Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 6:40 AM - 9:30 PM Monday 6:40 AM - 9:30 PM Maninagar Maninagar Railway Station, Ahmadābād Tuesday 6:40 AM - 9:30 PM Jawahar Chowk Wednesday 6:40 AM - 9:30 PM Bhairavnath Thursday 6:40 AM - 9:30 PM Friday 6:40 AM - 9:30 PM Sah Alam Darwaja Saturday 6:40 AM - 9:30 PM S. T. Stand Kamnath Mahadev / Raipur Darwaja Sarangpur 87 bus Info Direction: Chandkheda Kalupur Stops: 26 Trip Duration: 47 min Naroda Road, Ahmadābād Line Summary: Maninagar, Jawahar Chowk, Prem Darwaja Bhairavnath, Sah Alam Darwaja, S. T. Stand, Kamnath Mahadev / Raipur Darwaja, Sarangpur, Kalupur, Prem Darwaja, Dariyapur Darwaja, Delhi Dariyapur Darwaja Darwaja, Income Tax O∆ce, Usmanpura, Vadaj Bus Terminuss, Subhash Bridge, Keshav Nagar, Delhi Darwaja Dharmanagar, Ram Nagar, Chintamani Society, Abu Koba Cross Road, Gujarat Stadium, Motera Gam, Income Tax O∆ce Government Engineering College, Santokba Hospital, Shivshakti Nagar, Chandkheda Usmanpura Vadaj Bus Terminuss Subhash Bridge Keshav Nagar Dharmanagar Ram Nagar Chintamani Society Abu Koba Cross Road Ram Bag Road, Ahmadābād Gujarat Stadium -

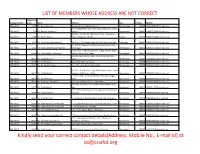

Kindly Send Your Correct Contact Details(Address, Mobile No., E-Mail Id) at [email protected] LIST of MEMBERS WHOSE ADDRESS ARE NOT CORRECT

LIST OF MEMBERS WHOSE ADDRESS ARE NOT CORRECT Membersh Category Name ip No. Name Address City PinCode EMailID IND_HOLD 6454 Mr. Desai Shamik S shivalik ,plot No 460/2 Sector 3 'c' Gandhi Nagar 382006 [email protected] Aa - 33 Shanti Nath Apartment Opp Vejalpur Bus Stand IND_HOLD 7258 Mr. Nevrikar Mahesh V Vejalpur Ahmedabad 380051 [email protected] Alomoni , Plot No. 69 , Nabatirtha , Post - Hridaypur , IND_HOLD 9248 Mr. Halder Ashim Dist - 24 Parganas ( North ) Jhabrera 743204 [email protected] IND_HOLD 10124 Mr. Lalwani Rajendra Harimal Room No 2 Old Sindhu Nagar B/h Sant Prabhoram Hall Bhavnagar 364002 [email protected] B-1 Maruti Complex Nr Subhash Chowk Gurukul Road IND_HOLD 52747 Mr. Kalaria Bharatkumar Popatlal Memnagar Ahmedabad 380052 [email protected] F/ 36 Tarun - Nagar Society Part - 2 Opp Vishram Nagar IND_HOLD 66693 Mr. Vyas Mukesh Indravadan Gurukul Road, Mem Nagar, Ahmedabad 380052 [email protected] 8, Keshav Kunj Society, Opp. Amar Shopping Centre, IND_HOLD 80951 Mr. Khant Shankar V Vatva, Ahmedabad 382440 [email protected] IND_HOLD 83616 Mr. Shah Biren A 114, Akash Rath, C.g. Road, Ahmedabad 380006 [email protected] IND_HOLD 84519 Ms. Deshpande Yogita A - 2 / 19 , Arvachin Society , Bopal Ahmedabad 380058 [email protected] H / B / 1 , Swastick Flat , Opp. Bhawna Apartment , Near IND_HOLD 85913 Mr. Parikh Divyesh Narayana Nagar Road , Paldi Ahmedabad 380007 [email protected] 9 , Pintoo Flats , Shrinivas Society , Near Ashok Nagar , IND_HOLD 86878 Ms. Shah Bhavana Paldi Ahmedabad 380006 [email protected] IND_HOLD 89412 Mr. Shah Rajiv Ashokbhai 119 , Sun Ville Row Houses , Mem Nagar , Ahmedabad 380052 [email protected] B4 Swetal Park Opp Gokul Rowhouse B/h Manezbaug IND_HOLD 91179 Mr. -

Sr. No Age Sex Address 1 64 M Sundarlal Ni Chali, Near

COVID ‐ 19 POSITIVE CASE LIST 05.05.2020, 08:00 PM SR. NO AGE SEX ADDRESS SUNDARLAL NI CHALI, NEAR SANGEETHA FURNITURE, 164M SAIJPUR, AHMEDABAD. 46, PATANI, SANJOGNAGAR, MEGHANINAGAR, 28F AHMEDABAD. 46, PATANI, SANJOGNAGAR, MEGHANINAGAR, 314F AHMEDABAD. 45, BHAVSAR NI CHALI, OPP. SHARDABEN HOSPITAL, 448M SARASPUR, AHMEDABAD. 5 57 M 753/3, AMBAVDI, SARDARNAGAR, AHMEDABAD. 6 25 F 753/2, AMBAVDI, SARDARNAGAR, AHMEDABAD. 7 28 F 753/2, AMBAVDI, SARDARNAGAR, AHMEDABAD. 8 26 M 753/3, AMBAVDI, SARDARNAGAR, AHMEDABAD. 9 8 M 753/3, AMBAVDI, SARDARNAGAR, AHMEDABAD. C‐2, SURDHARA SOCIETY, OPP. RAMINI CHALI, RAKHIAL, 10 35 F AHMEDABAD. C‐2, SURDHARA SOCIETY, OPP. RAMINI CHALI, RAKHIAL, 11 32 F AHMEDABAD. 54, BHOIWALA NI POLE, DILLI CHAKLA, SHAHPUR, 12 33 M AHMEDABAD. 52/1233, GUJRAT HOUSING BOARD, MEGHANINAGAR, 13 45 M AHMEDABAD. 6, HIREN APARTMENT, RAMNAGAR, SABARMATI, 14 53 M AHMEDABAD. 3603, MOTI VHORWAD, ASTODIYA KAJI NA DHABA, 15 56 F JAMALPUR, AHMEDABAD. A‐10, GUIMOHAR SOCIETY, NEAR THE NEW AGE SCHOOL, 16 55 M OPP. MEMON HALL, JUHAPURA‐SARKHEJ ROAD, AHMEDABAD. 206, 2/F, MADNI APARTMENT, KAZI NA DHABA, 17 54 F ASTODIA, AHMEDABAD. SR. NO AGE SEX ADDRESS 22, SHREEMAT SOCIETY, NR DUDHWALI CHALI, MELDI 18 62 F MATA NU MANDIR, BEHRAMPURA, AHMEDABAD. 181, SARVODAY NAGAR SOCIETY, OUTSIDE SHAHPUR 19 30 F GATE, SHAHPUR, AHMEDABAD. 20 75 F 1, MANMANDIR ROW HOUSE, VEJALPUR, AHMEDABAD. VASUDEV DHANJEE NICHALI, GITA MANDIR, 21 32 F AHMEDABAD. 45/K, RATAN POL, SHETH NI POL, MANEK CHOWK, 22 35 F AHMEDABAD. MAHAJAN NO VANDDO, VASANT NAGAR POLICE 23 50 M STATION SAME, JAMALPUR, AHMEDABAD. -

Compounding Injustice: India

INDIA 350 Fifth Ave 34 th Floor New York, N.Y. 10118-3299 http://www.hrw.org (212) 290-4700 Vol. 15, No. 3 (C) – July 2003 Afsara, a Muslim woman in her forties, clutches a photo of family members killed in the February-March 2002 communal violence in Gujarat. Five of her close family members were murdered, including her daughter. Afsara’s two remaining children survived but suffered serious burn injuries. Afsara filed a complaint with the police but believes that the police released those that she identified, along with many others. Like thousands of others in Gujarat she has little faith in getting justice and has few resources with which to rebuild her life. ©2003 Smita Narula/Human Rights Watch COMPOUNDING INJUSTICE: THE GOVERNMENT’S FAILURE TO REDRESS MASSACRES IN GUJARAT 1630 Connecticut Ave, N.W., Suite 500 2nd Floor, 2-12 Pentonville Road 15 Rue Van Campenhout Washington, DC 20009 London N1 9HF, UK 1000 Brussels, Belgium TEL (202) 612-4321 TEL: (44 20) 7713 1995 TEL (32 2) 732-2009 FAX (202) 612-4333 FAX: (44 20) 7713 1800 FAX (32 2) 732-0471 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] July 2003 Vol. 15, No. 3 (C) COMPOUNDING INJUSTICE: The Government's Failure to Redress Massacres in Gujarat Table of Contents I. Summary............................................................................................................................................................. 4 Impunity for Attacks Against Muslims............................................................................................................... -

Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation Councillor List (Term 2021-2026)

Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation Councillor List (term 2021-2026) Ward No. Sr. Mu. Councillor Address Mobile No. Name No. 1 1-Gota ARATIBEN KAMLESHBHAI CHAVDA 266, SHIVNAGAR (SHIV PARK) , 7990933048 VASANTNAGAR TOWNSHIP, GOTA, AHMEDABAD‐380060 2 PARULBEN ARVINDBHAI PATEL 291/1, PATEL VAS, GOTA VILLAGE, 7819870501 AHMEDABAD‐382481 3 KETANKUMAR BABULAL PATEL B‐14, DEV BHUMI APPARTMENT, 9924136339 SATTADHAR CROSS ROAD, SOLA ROAD, GHATLODIA, AHMEDABAD‐380061 4 AJAY SHAMBHUBHAI DESAI 15, SARASVATINAGAR, OPP. JANTA 9825020193 NAGAR, GHATLODIA, AHMEDABAD‐ 380061 5 2-Chandlodia RAJESHRIBEN BHAVESHBHAI PATEL H/14, SHAYONA CITY PART‐4, NR. R.C. 9687250254, 8487832057 TECHNICAL ROAD, CHANDLODIA‐ GHATLODIA, AHMDABAD‐380061 6 RAJESHWARIBEN RAMESHKUMAR 54, VINAYAK PARK, NR. TIRUPATI 7819870503, PANCHAL SCHOOL, CHANDLODIA, AHMEDABAD‐ 9327909986 382481 7 HIRABHAI VALABHAI PARMAR 2, PICKERS KARKHANA ,NR. 9106598270, CHAMUDNAGAR,CHANDLODIYA,AHME 9913424915 DABAD‐382481 8 BHARATBHAI KESHAVLAL PATEL A‐46, UMABHAVANI SOCIETY, TRAGAD 7819870505 ROAD, TRAGAD GAM, AHMEDABAD‐ 382470 9 3- PRATIMA BHANUPRASAD SAXENA BUNGLOW NO. 320/1900, Vacant due to Chandkheda SUBHASNAGAR, GUJ. HO.BOARD, resignation of Muni. CHANDKHEDA, AHMEDABAD‐382424 Councillor 10 RAJSHRI VIJAYKUMAR KESARI 2,SHYAM BANGLOWS‐1,I.O.C. ROAD, 7567300538 CHANDKHEDA, AHEMDABAD‐382424 11 RAKESHKUMAR ARVINDLAL 20, AUTAMNAGAR SOC., NR. D CABIN 9898142523 BRAHMBHATT FATAK, D CABIN SABARMATI, AHMEDABAD‐380019 12 ARUNSINGH RAMNYANSINGH A‐27,GOPAL NAGAR , CHANDKHEDA, 9328784511 RAJPUT AHEMDABAD‐382424 E:\BOARDDATA\2021‐2026\WEBSITE UPDATE INFORMATION\MUNICIPAL COUNCILLOR LIST IN ENGLISH 2021‐2026 TERM.DOC [ 1 ] Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation Councillor List (term 2021-2026) Ward No. Sr. Mu. Councillor Address Mobile No. Name No. 13 4-Sabarmati ANJUBEN ALPESHKUMAR SHAH C/O. BABULAL JAVANMAL SHAH , 88/A 079- 27500176, SHASHVAT MAHALAXMI SOCIETY, RAMNAGAR, SABARMATI, 9023481708 AHMEDABAD‐380005 14 HIRAL BHARATBHAI BHAVSAR C‐202, SANGATH‐2, NR. -

State Zone Commissionerate Name Division Name Range Name

Commissionerate State Zone Division Name Range Name Range Jurisdiction Name Gujarat Ahmedabad Ahmedabad South Rakhial Range I On the northern side the jurisdiction extends upto and inclusive of Ajaji-ni-Canal, Khodani Muvadi, Ringlu-ni-Muvadi and Badodara Village of Daskroi Taluka. It extends Undrel, Bhavda, Bakrol-Bujrang, Susserny, Ketrod, Vastral, Vadod of Daskroi Taluka and including the area to the south of Ahmedabad-Zalod Highway. On southern side it extends upto Gomtipur Jhulta Minars, Rasta Amraiwadi road from its intersection with Narol-Naroda Highway towards east. On the western side it extend upto Gomtipur road, Sukhramnagar road except Gomtipur area including textile mills viz. Ahmedabad New Cotton Mills, Mihir Textiles, Ashima Denims & Bharat Suryodaya(closed). Gujarat Ahmedabad Ahmedabad South Rakhial Range II On the northern side of this range extends upto the road from Udyognagar Post Office to Viratnagar (excluding Viratnagar) Narol-Naroda Highway (Soni ni Chawl) upto Mehta Petrol Pump at Rakhial Odhav Road. From Malaksaban Stadium and railway crossing Lal Bahadur Shashtri Marg upto Mehta Petrol Pump on Rakhial-Odhav. On the eastern side it extends from Mehta Petrol Pump to opposite of Sukhramnagar at Khandubhai Desai Marg. On Southern side it excludes upto Narol-Naroda Highway from its crossing by Odhav Road to Rajdeep Society. On the southern side it extends upto kulcha road from Rajdeep Society to Nagarvel Hanuman upto Gomtipur Road(excluding Gomtipur Village) from opposite side of Khandubhai Marg. Jurisdiction of this range including seven Mills viz. Anil Synthetics, New Rajpur Mills, Monogram Mills, Vivekananda Mill, Soma Textile Mills, Ajit Mills and Marsdan Spinning Mills. -

Three Years Later, When Cell Phones Ring

Best Breaking News THREE YEARS LATER, WHEN CELL PHONES RING Who spoke to whom, when Gujarat was burning Two CDs with more than 5 lakh entries have been lying with the Gujarat ** Using cellphone tower locations, the data also gives information on the police and are now with the Nanavati-Shah riots panel. These have records physical location of the caller and the person at the other end. of all cellphone calls made in Ahmedabad over the first five days of the riots which saw the worst massacres. PART ONE Two compact discs could change that. For, they contain records of all Tracking VHP’s gen secy on day 1,2 (published 21 November 2004) cellphone calls made in Ahmedabad from February 25, 2002, two days Vishwa Hindu Parishad’s General Secretary in Gujarat is a pathologist called before the horrific Sabarmati Express attack to March 4, five days that saw Jaideep Patel. He was booked for rioting and arson in the Naroda Patiya the worst communal violence in recent history. massacre, the worst post-Godhra riot incident in which 83 were killed, many of them burnt alive. The police closed the case saying there was not This staggering amount of data - there are more than 5 lakh entries - was enough evidence. Records show that Patel, who lives in Naroda, was there investigated over several weeks by this newspaper. They show that Patel when the massacre began, then left for Bapunagar which also witnessed was in touch with the key riot accused, top police officers, including the killings and returned to Naroda. -

Breathing Life Into the Constitution

Breathing Life into the Constitution Human Rights Lawyering In India Arvind Narrain | Saumya Uma Alternative Law Forum Bengaluru Breathing Life into the Constitution Human Rights Lawyering In India Arvind Narrain | Saumya Uma Alternative Law Forum Bengaluru Breathing Life into the Constitution Human Rights Lawyering in India Arvind Narrain | Saumya Uma Edition: January 2017 Published by: Alternative Law Forum 122/4 Infantry Road, Bengaluru - 560001. Karnataka, India. Design by: Vinay C About the Authors: Arvind Narrain is a founding member of the Alternative Law Forum in Bangalore, a collective of lawyers who work on a critical practise of law. He has worked on human rights issues including mass crimes, communal conflict, LGBT rights and human rights history. Saumya Uma has 22 years’ experience as a lawyer, law researcher, writer, campaigner, trainer and activist on gender, law and human rights. Cover page images copied from multiple news articles. All copyrights acknowledged. Any part of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted as necessary. The authors only assert the right to be identified wtih the reproduced version. “I am not a religious person but the only sin I believe in is the sin of cynicism.” Parvez Imroz, Jammu and Kashmir Civil Society Coalition (JKCSS), on being told that nothing would change with respect to the human rights situation in Kashmir Dedication This book is dedicated to remembering the courageous work of human rights lawyers, Jalil Andrabi (1954-1996), Shahid Azmi (1977-2010), K. Balagopal (1952-2009), K.G. Kannabiran (1929-2010), Gobinda Mukhoty (1927-1995), T. Purushotham – (killed in 2000), Japa Lakshma Reddy (killed in 1992), P.A. -

Special Report on Ahmedabad City, Part XA

PRG. 32A(N) Ordy. 700 CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 VOLUME V GUJARAT PAR T X-A (i) SPECIAL REPORT ON AHMEDABAD CITY R. K. TRIVEDI Superintendent of Census Operations, Gujarat PRICE Rs. 9.75 P. or 22 Sh. 9 d. or $ U.S. 3.51 CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 LIST OF PUBLICATIONS CENTRAL GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS Census of India, 1961 Volume V-Gujarat is being published in the following parts: * I-A(i) General Report * I-A(ii)a " * I-A(ii)b " * I-A(iii) General Report-Economic Trends and Projections :\< I-B Report on Vital Statistics and Fertility Survey .\< I-C Subsidiary Tables -'" II-A General Population Tables * II-B(l) General Economic Tables (Tables B-1 to B-IV-C) * II-B(2) General Economic Tables (Tables B-V to B-IX) * II-C Cultural and Migration Tables :l< III Household Economic Tables (Tables B-X to B-XVII) * IV-A Report on Housing and Establishments * IV-B Housing and Establishment Tables :\< V-A Tables on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes V-B Ethnographic Notes on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (including reprints) ** VI Village Survey Monographs (25 Monographs) VII-A Selected Crafts of Gujarat * VII-B Fairs and Festivals * VIII-A Administration Report-Enumeration " ~ N ~r£br Sale - :,:. _ _/ * VIII-B Administration Report-Tabulation ) :\' IX Atlas Volume X-A Special Report on Cities * X-B Special Tables on Cities and Block Directory '" X-C Special Migrant Tables for Ahmedabad City STATE GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS * 17 District Census Handbooks in English * 17 District Census Handbooks in Gl~arati " Published ** Village Survey Monographs for SC\-Cu villages, Pachhatardi, Magdalla, Bhirandiara, Bamanbore, Tavadia, Isanpur and Ghclllvi published ~ Monographs on Agate Industry of Cam bay, Wood-carving of Gujarat, Patara Making at Bhavnagar, Ivory work of i\1ahllva, Padlock .i\Iaking at Sarva, Seellc l\hking of S,v,,,-kundb, Perfumery at Palanpur and Crochet work of Jamnagar published - ------------------- -_-- PRINTED BY JIVANJI D.