MARY D. GARRARD, Artemisia Gentileschi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Woman-Slave Analogy: Rhetorical Foundations in American

The Woman-Slave Analogy: Rhetorical Foundations in American Culture, 1830-1900 Ana Lucette Stevenson BComm (dist.), BA (HonsI) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2014 School of History, Philosophy, Religion and Classics I Abstract During the 1830s, Sarah Grimké, the abolitionist and women’s rights reformer from South Carolina, stated: “It was when my soul was deeply moved at the wrongs of the slave that I first perceived distinctly the subject condition of women.” This rhetorical comparison between women and slaves – the woman-slave analogy – emerged in Europe during the seventeenth century, but gained peculiar significance in the United States during the nineteenth century. This rhetoric was inspired by the Revolutionary Era language of liberty versus tyranny, and discourses of slavery gained prominence in the reform culture that was dominated by the American antislavery movement and shared among the sisterhood of reforms. The woman-slave analogy functioned on the idea that the position of women was no better – nor any freer – than slaves. It was used to critique the exclusion of women from a national body politic based on the concept that “all men are created equal.” From the 1830s onwards, this analogy came to permeate the rhetorical practices of social reformers, especially those involved in the antislavery, women’s rights, dress reform, suffrage and labour movements. Sarah’s sister, Angelina, asked: “Can you not see that women could do, and would do a hundred times more for the slave if she were not fettered?” My thesis explores manifestations of the woman-slave analogy through the themes of marriage, fashion, politics, labour, and sex. -

Mother Trouble: the Maternal-Feminine in Phallic and Feminist Theory in Relation to Bratta Ettinger's Elaboration of Matrixial Ethics

This is a repository copy of Mother trouble: the maternal-feminine in phallic and feminist theory in relation to Bratta Ettinger's Elaboration of Matrixial Ethics. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/81179/ Article: Pollock, GFS (2009) Mother trouble: the maternal-feminine in phallic and feminist theory in relation to Bratta Ettinger's Elaboration of Matrixial Ethics. Studies in the Maternal, 1 (1). 1 - 31. ISSN 1759-0434 Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Mother Trouble: The Maternal-Feminine in Phallic and Feminist Theory in Relation to Bracha Ettinger’s Elaboration of Matrixial Ethics/Aesthetics Griselda Pollock Preface Most of us are familiar with Sigmund Freud’s infamous signing off, in 1932, after a lifetime of intense intellectual and analytical creativity, on the question of psychoanalytical research into femininity. -

Lucas Van Leyden: Prints from the Testaments La Salle University Art Museum

La Salle University La Salle University Digital Commons Art Museum Exhibition Catalogues La Salle University Art Museum 3-1984 Lucas Van Leyden: Prints from the Testaments La Salle University Art Museum Brother Daniel Burke FSC Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/exhibition_catalogues Part of the Fine Arts Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation La Salle University Art Museum and Burke, Brother Daniel FSC, "Lucas Van Leyden: Prints from the Testaments" (1984). Art Museum Exhibition Catalogues. 74. http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/exhibition_catalogues/74 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the La Salle University Art Museum at La Salle University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Art Museum Exhibition Catalogues by an authorized administrator of La Salle University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Lucas van Leyden Prints Frcm The Testaments LaSalle College Art Museum March 1 - April 30, 1984 For many years, students of In. Salle College had the privilege of pursuing a course in the history of graphic art at the Alverthorpe Gallery in nearby Jenkintown. Lessing Rosenwald himself would on occasion join our Professor Ihomas Ridington or Herman Gundersheimer and the students for an afternoon with Rerrbrandt, Durer, or Lucas van Leyden. After Mr. Rosenwald's death and the transfer of his collection to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, the course had to be pursued, it need hardly be said, in much reduced circunstances. But the present exhibition, which returns many of Mr. Rosenwald's Lucas van Leyden prints from the National Gallery to the Rosenwald Roc*n in the La Salle Museum, recreates briefly for us the happy circumstances of earlier, halcyon days. -

The Symbolism of Blood in Two Masterpieces of the Early Italian Baroque Art

The Symbolism of blood in two masterpieces of the early Italian Baroque art Angelo Lo Conte Throughout history, blood has been associated with countless meanings, encompassing life and death, power and pride, love and hate, fear and sacrifice. In the early Baroque, thanks to the realistic mi of Caravaggio and Artemisia Gentileschi, blood was transformed into a new medium, whose powerful symbolism demolished the conformed traditions of Mannerism, leading art into a new expressive era. Bearer of macabre premonitions, blood is the exclamation mark in two of the most outstanding masterpieces of the early Italian Seicento: Caravaggio's Beheading a/the Baptist (1608)' (fig. 1) and Artemisia Gentileschi's Judith beheading Halo/ernes (1611-12)2 (fig. 2), in which two emblematic events of the Christian tradition are interpreted as a representation of personal memories and fears, generating a powerful spiral of emotions which constantly swirls between fiction and reality. Through this paper I propose that both Caravaggio and Aliemisia adopted blood as a symbolic representation of their own life-stories, understanding it as a vehicle to express intense emotions of fear and revenge. Seen under this perspective, the red fluid results as a powerful and dramatic weapon used to shock the viewer and, at the same time, express an intimate and anguished condition of pain. This so-called Caravaggio, The Beheading of the Baptist, 1608, Co-Cathedral of Saint John, Oratory of Saint John, Valletta, Malta. 2 Artemisia Gentileschi, Judith beheading Halafernes, 1612-13, Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte, Naples. llO Angelo La Conte 'terrible naturalism'3 symbolically demarks the transition from late Mannerism to early Baroque, introducing art to a new era in which emotions and illusion prevail on rigid and controlled representation. -

Bracha L. Ettinger's the Matrixial Borderspace

Seduction into Reading: 1 Bracha L. Ettinger’s The Matrixial Borderspace Noreen Giffney, Anne Mulhall and Michael O’Rourke Bracha’s Blessing Bracha L. Ettinger in her studio, 2009 (photo: A. Berlowitz) Bracha L. Ettinger, born in Tel Aviv, is a contemporary artist (mainly producing drawings and paintings), a senior clinical psychologist, and a practicing psychoanalyst, who interweaves and enmeshes all three domains by practising what she calls ‘matrixial painting’, a process which challenges the phallic structuration of the Symbolic. Her visual poiesis uncovers the complicities between the twin erasures of sexual difference and jewish difference and this disclosure (rather than foreclosure) of the feminine and the jew in her writing/painting brings about a wholescale reconfiguration of both Western aesthetics and of the (putatively masculine) gaze. 2 Her matrixial artworks have been 2 exhibited extensively in major museums of contemporary art, including The Drawing Center in New York (2001) and most recently in exhibitions at The Freud Museum in London curated by Griselda Pollock (2009) and The Finnish Art Academy in Helsinki (2009). Bracha’s oeuvre , or, better, her oeuverture , a corpus which emphasises an open gravitational mobility, includes a number of books and essays on topics relating to psychoanalysis, philosophy, visual culture, feminism and ethics. 3 Her writing extends and challenges the work of contemporary philosophers and psychoanalysts (many of whom are her friends) including Emmanuel Lévinas, Jean-François Lyotard, Gilles Deleuze, Félix Guattari, Jacques Lacan, Julia Kristeva, Edmond Jabès and Luce Irigaray. A groundbreaking theoretician, Bracha works at the intersection or borderline between feminism, psychoanalysis and aesthetics and for over two decades she has been forging or weaving a new ‘matrixial’ theory and language with major aesthetical, analytical, political, and most crucially ethical implications. -

Griselda Pollock Feminist Interventions in Art's Histories* Is

Griselda Pollock Feminist Interventions in Art's Histories* 1 * Der Beitrag ist eine Is adding women to art history the same as producing feminist art history? Deman gekiirzte Fassung des ding that women be considered, not only changes what is studied and what becomes Vorworteszu dem Buch: Griselda Pollock (Hrsg.), relevant to investigate, but it challenges the existing disciplines politically. Women Vision and Difference. have not been omitted through forgetfulness or mere prejudice. The structural Feminism, Feminity and sexism of most academic disciplines contributes actively to the production and per Histories of Art, Methuen, 1987. petuation of a gender hierarchy. What we learn about the world and its peoples is ideologically patterned in conformity with the social order within which it is produ ced. Women's studies are not just about women but about the social systems and ideological schemas which sustain the domination of men over women within the other mutually inflecting regimes of power in the world, namely those of class and those of race.2 Feminist art history, however, began inside art history. The first question was »Have there been women artists?« We initially thought about women artists in terms of art history's typical procedures and protocols studies of artists (the mono graph) , collections of works to make an oeuvre (catalogues raisonnes), questions of style and iconography, membership of movements and artists' groups, and of course the question of quality. It soon became clear that this would be a straitjacket in which our studies of women artists would reproduce and secure the normative status of men artists and men's art whose superiority was unquestioned in its dis 1 Freely paraphrased from guise as Art and the Artist. -

Unequal Lovers: a Study of Unequal Couples in Northern Art

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications and Creative Activity, School of Art, Art History and Design Art, Art History and Design, School of 1978 Unequal Lovers: A Study of Unequal Couples in Northern Art Alison G. Stewart University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/artfacpub Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Stewart, Alison G., "Unequal Lovers: A Study of Unequal Couples in Northern Art" (1978). Faculty Publications and Creative Activity, School of Art, Art History and Design. 19. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/artfacpub/19 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Art, Art History and Design, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications and Creative Activity, School of Art, Art History and Design by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Unequal Lovers Unequal Lovers A Study of Unequal Couples in Northern Art A1ison G. Stewart ABARIS BOOKS- NEW YORK Copyright 1977 by Walter L. Strauss International Standard Book Number 0-913870-44-7 Library of Congress Card Number 77-086221 First published 1978 by Abaris Books, Inc. 24 West 40th Street, New York, New York 10018 Printed in the United States of America This book is sold subject to the condition that no portion shall be reproduced in any form or by any means, and that it shall not, by way of trade, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise disposed of without the publisher's consent, in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published. -

ARTEMISIA GENTILESCHI ARTEMISIA ARTEMISIA GENTILESCHI E Il Suo Tempo

ARTEMISIA GENTILESCHI ARTEMISIA GENTILESCHI e il suo tempo Attraverso un arco temporale che va dal 1593 al 1653, questo volume svela gli aspetti più autentici di Artemisia Gentileschi, pittrice di raro talento e straordinaria personalità artistica. Trenta opere autografe – tra cui magnifici capolavori come l’Autoritratto come suonatrice di liuto del Wadsworth Atheneum di Hartford, la Giuditta decapita Oloferne del Museo di Capodimonte e l’Ester e As- suero del Metropolitan Museum di New York – offrono un’indagine sulla sua carriera e sulla sua progressiva ascesa che la vide affermarsi a Firenze (dal 1613 al 1620), Roma (dal 1620 al 1626), Venezia (dalla fine del 1626 al 1630) e, infine, a Napoli, dove visse fino alla morte. Per capire il ruolo di Artemisia Gentileschi nel panorama del Seicento, le sue opere sono messe a confronto con quelle di altri grandi protagonisti della sua epoca, come Cristofano Allori, Simon Vouet, Giovanni Baglione, Antiveduto Gramatica e Jusepe de Ribera. e il suo tempo Skira € 38,00 Artemisia Gentileschi e il suo tempo Roma, Palazzo Braschi 30 novembre 2016 - 7 maggio 2017 In copertina Artemisia Gentileschi, Giuditta che decapita Oloferne, 1620-1621 circa Firenze, Gallerie degli Uffizi, inv. 1597 Virginia Raggi Direzione Musei, Presidente e Capo Ufficio Stampa Albino Ruberti (cat. 28) Sindaca Ville e Parchi storici Amministratore Adele Della Sala Amministratore Delegato Claudio Parisi Presicce, Iole Siena Luca Bergamo Ufficio Stampa Roberta Biglino Art Director Direttore Marcello Francone Assessore alla Crescita -

Download Download

Journal of Arts & Humanities Volume 09, Issue 06, 2020: 01-11 Article Received: 26-04-2020 Accepted: 05-06-2020 Available Online: 13-06-2020 ISSN: 2167-9045 (Print), 2167-9053 (Online) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18533/journal.v9i6.1920 Caravaggio and Tenebrism—Beauty of light and shadow in baroque paintings Andy Xu1 ABSTRACT The following paper examines the reasons behind the use of tenebrism by Caravaggio under the special context of Counter-Reformation and its influence on later artists during the Baroque in Northern Europe. As Protestantism expanded throughout the entire Europe, the Catholic Church was seeking artistic methods to reattract believers. Being the precursor of Counter-Reformation art, Caravaggio incorporated tenebrism in his paintings. Art historians mostly correlate the use of tenebrism with religion, but there have also been scholars proposing how tenebrism reflects a unique naturalism that only belongs to Caravaggio. The paper will thus start with the introduction of tenebrism, discuss the two major uses of this artistic technique and will finally discuss Caravaggio’s legacy until today. Keywords: Caravaggio, Tenebrism, Counter-Reformation, Baroque, Painting, Religion. This is an open access article under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. 1. Introduction Most scholars agree that the Baroque range approximately from 1600 to 1750. There are mainly four aspects that led to the Baroque: scientific experimentation, free-market economies in Northern Europe, new philosophical and political ideas, and the division in the Catholic Church due to criticism of its corruption. Despite the fact that Galileo's discovery in astronomy, the Tulip bulb craze in Amsterdam, the diplomatic artworks by Peter Paul Rubens, the music by Johann Sebastian Bach, the Mercantilist economic theories of Colbert, the Absolutism in France are all fascinating, this paper will focus on the sophisticated and dramatic production of Catholic art during the Counter-Reformation ("Baroque Art and Architecture," n.d.). -

Possibilities for Feminist Scenic Design Raynette Halvorsen Smith

Spring 1990 153 Intersections Between Feminism and Post-modernism: Possibilities For Feminist Scenic Design Raynette Halvorsen Smith Introduction Is there latitude in the profession of scenic design for feminist artistic expression? Is it possible to locate a practice in scene design which can shift the feminist critique from the margins to the center of this craft? Or is this profession of scenic design, the oldest recognized design area, too steeped in patriarchal theatre culture to admit feminist expression and retain its identity? It is my position that Post-modernism creates a context that would allow feminist expression in scenic design, expression which, until recent develop ments in feminist theory, has not been possible. This exploration of feminism and Post-modernism cannot outline the details of a new feminist scenic practice, but only point to ideas, directions, and tendencies which allow for such a possibility. First I should clarify what is meant by "feminist expression." There is danger of eliding opposing feminist ideologies in the attempt to characterize this expression. However, in an essay titled "Feminist Art and Avant- Gardism," Angela Partington outlines two important premises broad enough to encompass differences in feminist ideology. She expands feminist expression into the term "feminist art practice" with two major criteria. These are defined as: Raynette Halvorsen Smith is a professional scenic designer and a member of United Scenic Artists Local 829. She has written a number of articles on feminism and design, most notably "Where Are the American Women Scene Designers?", for which she received the Herbert D. Greggs Award from the United States Institute of Theatre Technology. -

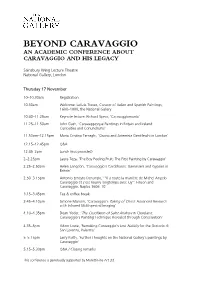

Programme for Beyond Caravaggio

BEYOND CARAVAGGIO AN ACADEMIC CONFERENCE ABOUT CARAVAGGIO AND HIS LEGACY Sainsbury Wing Lecture Theatre National Gallery, London Thursday 17 November 10–10.30am Registration 10.30am Welcome: Letizia Treves, Curator of Italian and Spanish Paintings, 1600–1800, the National Gallery 10.40–11.25am Keynote lecture: Richard Spear, ‘Caravaggiomania’ 11.25–11.50am John Gash, ‘Caravaggesque Paintings in Britain and Ireland: Curiosities and Conundrums’ 11.50am–12.15pm Maria Cristina Terzaghi, ‘Orazio and Artemisia Gentileschi in London’ 12.15–12.45pm Q&A 12.45–2pm Lunch (not provided) 2–2.25pm Laura Teza, ‘The Boy Peeling Fruit: The First Painting by Caravaggio’ 2.25–2.50pm Helen Langdon, ‘Caravaggio's Cardsharps: Gamesters and Gypsies in Britain’ 2.50–3.15pm Antonio Ernesto Denunzio, ‘“Il a toute la manière de Michel Angelo Caravaggio et s'est nourry longtemps avec luy”: Finson and Caravaggio, Naples 1606–10’ 3.15–3.45pm Tea & coffee break 3.45–4.10pm Simone Mancini, ‘Caravaggio's Taking of Christ: Advanced Research with Infrared Multispectral Imaging’ 4.10–4.35pm Dean Yoder, ‘The Crucifixion of Saint Andrew in Cleveland: Caravaggio’s Painting Technique Revealed through Conservation’ 4.35–5pm Adam Lowe, ‘Remaking Caravaggio’s Lost Nativity for the Oratorio di San Lorenzo, Palermo’ 5–5.15pm Larry Keith, ‘Further Thoughts on the National Gallery’s paintings by Caravaggio’ 5.15–5.30pm Q&A / Closing remarks This conference is generously supported by Moretti Fine Art Ltd. BEYOND CARAVAGGIO AN ACADEMIC CONFERENCE ABOUT CARAVAGGIO AND HIS LEGACY Sainsbury -

Artemisia Gentileschi : the Heart of a Woman and the Soul of a Caesar

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 7-13-2010 Artemisia Gentileschi : The eH art of a Woman and the Soul of a Caesar Deborah Anderson Silvers University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Silvers, Deborah Anderson, "Artemisia Gentileschi : The eH art of a Woman and the Soul of a Caesar" (2010). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/3588 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Artemisia Gentileschi : The Heart of a Woman and the Soul of a Caesar by Deborah Anderson Silvers A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Liberal Arts Department of Humanities and Cultural Studies College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Naomi Yavneh, Ph.D. Annette Cozzi, Ph.D. Giovanna Benadusi, Ph.D. Date of Approval: July 13, 2010 Keywords: Baroque, Susanna and the Elders, self referential Copyright © 2010, Deborah Anderson Silvers DEDICATION I would like to dedicate this thesis to my husband, Fon Silvers. Nearly seven years ago, on my birthday, he told me to fulfill my long held dream of going back to school to complete a graduate degree. He promised to support me in every way that he possibly could, and to be my biggest cheerleader along the way.