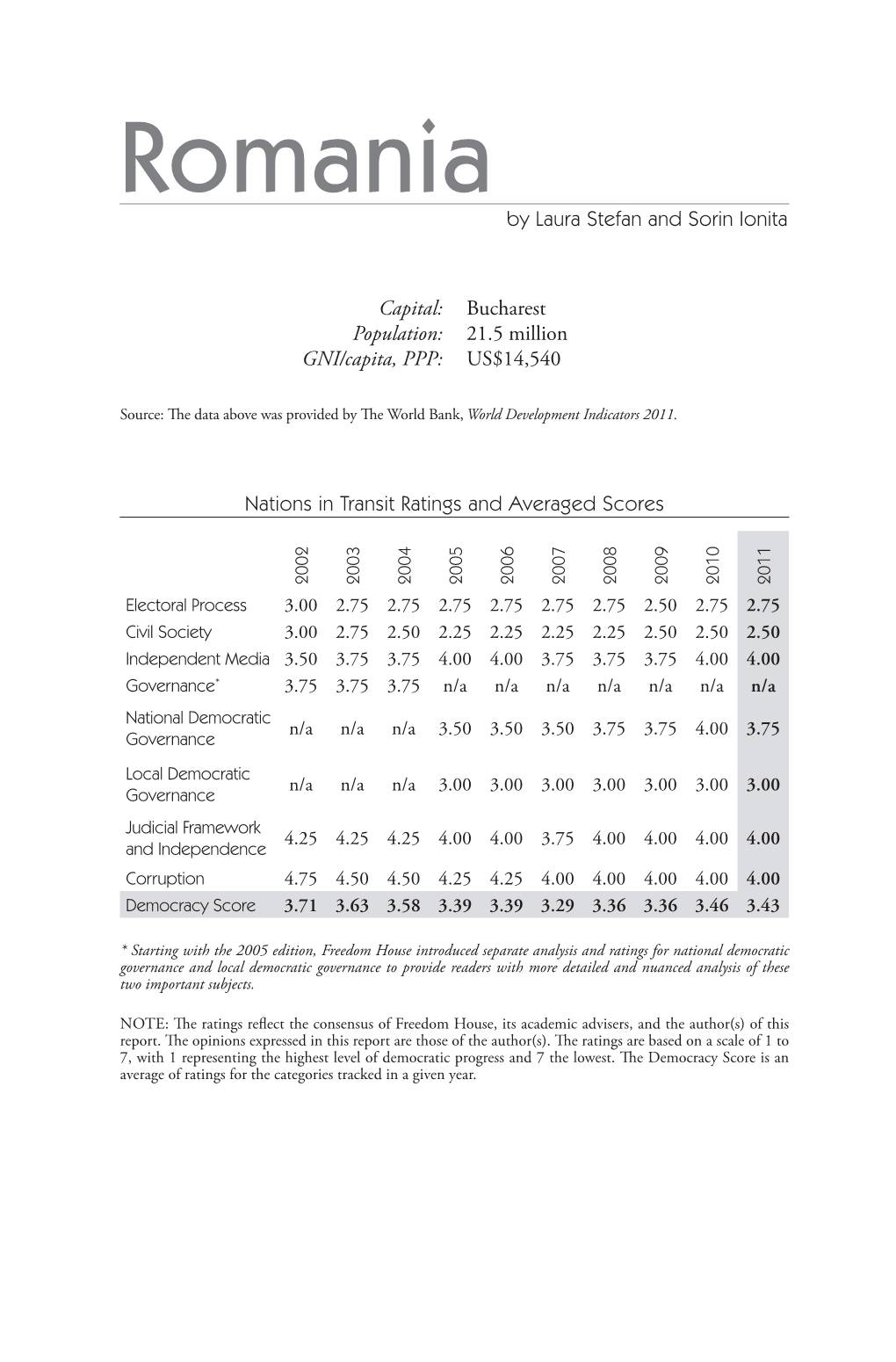

Romania by Laura Stefan and Sorin Ionita

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Curriculum Vitae Europass Personal Information Name, Surname E-Mail Nationality Florin Zeru [email protected] Romani

Curriculum vitae Europass Personal information Name, Surname Florin Zeru E-mail [email protected] Nationality Romanian Professional experience Employer’s name Eurocommunication Association 65 Dej St., Bucharest 1, Romania Activity field Non-governmental, non-profit organization Period December 2020 - present Function Project manager Activities and Florin Zeru is project manager within the project Strategy for the management of the responsibilities Romanian governmental communication, carried out in partnership with the General Secretariat of the Romanian Government. The decision to be selected to that position was based on the solid experience of Florin in the field of European funds. ”Strategy for the management of the Romanian governmental communication” - The aim of the project is to improve and unite the governmental communication at the level of the central public administration in Romania. Period: December 2020 – April 2023 Beneficiary: General Secretariat of the Romanian Government Specific tasks: Coordinates plans and is responsible for the efficient organization and implementation of the activities approved by the project at the Partner level; Ensures and is responsible for the correctness, legality, necessity, and timeliness of operations related to the implementation of the project; Effectively solves unforeseen administrative problems and communicates to the project manager (SGG) about those problems that exceed its decision-making level; Proposes ways to improve administrative activity and ensures the application of changes approved by the project manager (SGG); Supervises compliance with the requirements of the financing contract. Propose amendments to the financing agreement (where applicable); Checks and validates the quality of the documents produced within the project; Participates in Project-level meetings and/or meetings with MA POCA or other management/control institutions. -

Anti-Corruption Policies Revisited Computer Assiste

EU Grant Agreement number: 290529 Project acronym: ANTICORRP Project title: Anti-Corruption Policies Revisited Work Package: WP 6 Media and corruption Title of deliverable: D 6.1 Extensive content analysis study on the coverage of stories on corruption Computer Assisted Content Analysis of the print press coverage of corruption In Romania Due date of deliverable: 30 June, 2016 Actual submission date: 30 June, 2016 Authors: Natalia Milewski , Valentina Dimulescu (SAR) Organization name of lead beneficiary for this deliverable: UNIPG, UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI PERUGIA Project co-funded by the European Commission within the Seventh Framework Programme Dissemination level PU Public X PP Restricted to other programme participants (including the Commission Services) RE Restricted to a group specified by the consortium (including the Commission Services) Co Confidential, only for members of the consortium (including the Commission Services) The information and views set out in this publication are those of the author(s) only and do not reflect any collective opinion of the ANTICORRP consortium, nor do they reflect the official opinion of the European Commission. Neither the European Commission nor any person acting on behalf of the European Commission is responsible for the use which might be made of the following information. 1 CONTENTS 1. The Analysed Media p. 3 2. Most used keywords p.4 3. Most frequent words p.5 4. Word associations p. 13 5. Evolution over time p. 25 6. Differences among the observed newspapers p. 29 7. Remarks on the influence that the political, judicial and socio-cultural systems have on p. 33 the manner in which corruption is portrayed in Romanian media 8. -

Scientific Exorcisms? the Memory of the Communist Security Apparatus

285 Stefano Bottoni PhD University of Florence, Italy ORCID: 0000-0002-2533-2250 SCIENTIFIC EXORCISMS? ARTICLES THE MEMORY OF THE COMMUNIST SECURITY APPARATUS AND ITS STUDY IN ROMANIA AFTER 1989 Abstract This article discusses the institutional attempts to deal with the archival legacy of the Romanian communist security police, Securitate (1945–1989), during the democratic transition in post-communist Romania. The first part draws a short outline of Securitate’s history and activities as one of the main power instruments of the communist dictatorship. The second part of the article shows the development of political attitudes towards institutional attempts to deal with the communist past in the post-communist Romania. This paper describes the reluctant attitude of the ruling circles in the 1990s towards the opening of the Securitate archives and the lustration attempts. The formation of the National Council for the Study of Securitate Archives (Consiliul Național pentru Studierea Arhivelor Securității, CNSAS, legally established 1999) hardly changed the general situation: the archives of the Securitate were transferred to CNSAS with significant delays, and the 2008 ruling of the constitutional court limited its lustration competences. The establishment of the Institute for the Investigation of Communist Crimes and the Memory of the Romanian Exile (Institutul de Investigare a Crimelor Comunismului şi Memoria Exilului Românesc, IICCMER, established 2005) and formation in 2006 of the Presidential Commission for the Analysis of the Communist Dictatorship Institute of National Remembrance 2/2020 286 in Romania led by renowned political scientist Vladimir Tismăneanu together with the research and legal activities of CNSAS contributed to a broader evaluation of the communist regime (although its impact seems to be limited). -

Communism and Post-Communism in Romania : Challenges to Democratic Transition

TITLE : COMMUNISM AND POST-COMMUNISM IN ROMANIA : CHALLENGES TO DEMOCRATIC TRANSITION AUTHOR : VLADIMIR TISMANEANU, University of Marylan d THE NATIONAL COUNCIL FO R EURASIAN AND EAST EUROPEAN RESEARC H TITLE VIII PROGRA M 1755 Massachusetts Avenue, N .W . Washington, D .C . 20036 LEGAL NOTICE The Government of the District of Columbia has certified an amendment of th e Articles of Incorporation of the National Council for Soviet and East European Research changing the name of the Corporation to THE NATIONAL COUNCIL FOR EURASIAN AND EAST EUROPEAN RESEARCH, effective on June 9, 1997. Grants, contracts and all other legal engagements of and with the Corporation made unde r its former name are unaffected and remain in force unless/until modified in writin g by the parties thereto . PROJECT INFORMATION : 1 CONTRACTOR : University of Marylan d PR1NCIPAL 1NVEST1GATOR : Vladimir Tismanean u COUNCIL CONTRACT NUMBER : 81 1-2 3 DATE : March 26, 1998 COPYRIGHT INFORMATIO N Individual researchers retain the copyright on their work products derived from research funded by contract with the National Council for Eurasian and East European Research . However, the Council and the United States Government have the right to duplicate an d disseminate, in written and electronic form, this Report submitted to the Council under thi s Contract, as follows : Such dissemination may be made by the Council solely (a) for its ow n internal use, and (b) to the United States Government (1) for its own internal use ; (2) for further dissemination to domestic, international and foreign governments, entities an d individuals to serve official United States Government purposes ; and (3) for dissemination i n accordance with the Freedom of Information Act or other law or policy of the United State s Government granting the public rights of access to documents held by the United State s Government. -

Monitoring Facebook. Presidential Elections – Romania, November 2019

Monitoring Facebook. Presidential Elections – Romania, November 2019 A report drafted by GlobalFocus Center, Bucharest, in cooperation with MEMO98, Bratislava. Supported by Democracy Reporting International, Berlin. Monitoring Facebook. Presidential Elections – Romania, November 2019 Monitoring Facebook. Presidential Elections – Romania, November 2019 February, 2019 Bucharest, Romania This project was supported by Civitates Monitoring Facebook. Presidential Elections – Romania, November 2019 GlobalFocus Center is an independent international studies’ think tank that produces in-depth research and high-quality analysis on foreign policy, security, European aairs, good governance, and development. Our purpose is to advance expertise by functioning as a platform for cooperation and dialogue among individual experts, NGOs, think-tanks, and public institutions from Romania and foreign partners. We have built, and tested over 10 dierent countries a unique research methodology, proactively approaching the issue of malign interference by analysing societies' structural, weaponisable vulnerabilities. We are building a multi-stakeholder Stratcom platform, for identifying an optimal way of initiating and conducting unied responses to hybrid threats. Our activities are focused on fostering regional security and contributing to the reection process of EU reforms. During November 1-24, 2019, GlobalFocus Center, in cooperation with MEMO98 and Democracy Reporting International (DRI), monitored Facebook during the 10 and 24 November presidential election polls in Romania. AUTHORS GlobalFocus Center: Ana Maria Luca, Run Zamr (editor) ANALYSTS: Alexandra Mihaela Ispas, Ana Maria Teaca, Vlad Iavita, Raluca Andreescu MEMO98: Rasťo Kužel Monitoring Facebook. Presidential Elections – Romania, November 2019 Contents I. INTRODUCTION 4 II. HIGHLIGHTS 5 III. CONTEXT 6 III.1 TRUST IN MEDIA AND SOCIAL MEDIA CONSUMPTION IN ROMANIA 6 III.2 PUBLIC ATTITUDES AND TRUST IN INSTITUTIONS 7 III.3 THE NOVEMBER 2019 PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION 7 IV. -

The Impact of the European Union on Corruption in Romania

The Impact of the European Union on Corruption in Romania Alexandru Hirsu Hamilton College Advisor: Alan Cafruny, Ph. D. Professor of Government Levitt Research Fellowship-Summer 2015 Abstract After the revolution of 1989, Romania confronted with high levels of corruption, and had a difficult time strengthening its democratic process. 10 years later, when the country became an official candidate for accession to the European Union (EU), the Romanian democracy saw hope for consolidation. However, despite the expertise and resources provided by the EU until 2007 in order for Romania to meet the acquis communautaire, the EU failed to bring about sustainable change. An incomplete European framework with guidelines tailored to Romania’s fragile democracy, and inadequate monitoring of the country’s political actions were the main causes for Romania’s slow democratic consolidation. The paper provides an analysis on Romania’s fight against corruption with a focus on the development of the anticorruption agencies, the rule of law, and the public administration from 2006 to 2012. Introduction Although scholarly attention upon corruption has grown over the past years and the number of soft and hard legislative tools to combat corruption has increased, corruption today still represents one of the main threats to the stability of democratic governments. In post- communist satellite states, in particular, corruption has remained a more prevalent issue. Leslie Holmes referred to it as “a rising tide of sleaze in ex-communist Europe,” claiming that “corruption has replaced communism as the scourge of Eastern Europe” (2013, 1163). As an ex- communist state itself, Romania has struggled endlessly with corruption over the past twenty five years. -

The Novelty of the Romanian Press

The Novelty of the Romanian Press Lorela Corbeanu School of Arts and Science Nottingham Trent University - UK [email protected] ABSTRACT High level political corruption has been a constant problem of post-communist Romania, long indicated by international bodies. This continuing situation raises questions about the capacity of the Romanian institutions to reform and fulfill their duties. Among these institutions, the Romanian Press occupies a special place due to its nature and to its connection with politics. This paper will offer an image of the relationship between the post- communist Romanian press and the political world and will point towards a few elements that make it a unique case that deserves to be carefully researched. KEYWORDS Mass-media, moguls, press, political corruption Romania. INTRODUCTION Romanian media moguls are different from In a general negative context, marked by other cases in the post-communist world. reports from the European Commission I will examine two different Romanian (EC Reports on Romania, 2011 – 2004) cases, Sorin Ovidiu Vantu and Dan and other international bodies, pointing to Voiculescu and compare them to other two the severe high level political corruption cases, Paval Rusko form Slovakia and problem, the role of the press as guaranty Vladimir Zelenzy from the Czech Republic. of democracy, transparency and state of The reason I have chosen these cases is to law becomes more relevant than ever. The exemplify how tight the relationship role the press plays in these kinds of between media and politics is in Romania. troubled situations is the ultimate test to I shall continue with a trip through the show the level and the quality of press in history of the Romanian press to underline a particular country. -

Gender and Elections in Romania

GENDER AND ELECTIONS IN ROMANIA ABSTRACT UNDP has been undertaking a series of case study research projects about the opportunities and challenges for ZRPHQ¶VSDUWLFLSDWLRQDVYoters in the Europe CIS region. The present case study presents an analysis of gender and the electoral legislation reform process in Romania, focusing on two aspects of the legal framework factor: WKHHIIHFWRIWKHHOHFWRUDOV\VWHPRQZRPHQ¶VSDUWLFLSDWLRQDQGJHQGHUTXRWDVDVPHDQVRIHQKDQFLQJZRPHQ¶V descriptive representation. An important entry point is to acknowledge that low participation and representation of ZRPHQLVDVHULRXVLVVXHWKDWLPSDFWV5RPDQLD¶VGHPRFUDWL]DWLRQSURFHVV2QWKLVSDWKWRZDrds gender equality in politics, representatives of civil society should be carefully monitoring political actors who may have learned and are skilled at using the discourse of gender equality, but less so the practice. Future public discussions and debates on political participation and representation should focus on the role of political parties in shaping specific democratic differences. The debates should also emphasize the role of the electoral system in ensuring adequate representation of women. If change towards more gender equality in politics is needed, the joint efforts of all key actors are required. TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 1. INTRODUCTION 5 2. METHODOLOGY 6 3. BACKGROUND: WOMEN IN POLITICS BEFORE 1989 7 3.1 RECLAIMING POLITICAL RIGHTS: 19TH AND EARLY 20TH CENTURY 7 3.2 POLITICAL COMRADES DURING COMMUNISM: 1947-1989 8 4. BACKGROUND: WOMEN IN POLITICS AFTER 1989 9 4.1 WOMEN IN THE PARLIAMENT AND LOCAL POLITICS 9 4.2 GENDER EQUALITY AND THE LEGISLATIVE ELECTORAL FRAMEWORK 10 4.3 MORE WOMEN IN POLITICS: FIGHTING FOR GENDER QUOTAS 12 4.3.1 Mandatory (Legislative) Gender Quotas 12 4.3.2 Voluntary (Party) Gender Quotas 13 4.4 INTERNATIONAL SUPPORT FOR MORE WOMEN IN POLITICS: UNDP 14 5. -

Territorial Dimensions of the Romanian Parties: Elections, Party Rules and Organisations Ionescu, Alexandra

www.ssoar.info Territorial dimensions of the Romanian parties: elections, party rules and organisations Ionescu, Alexandra Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Ionescu, A. (2012). Territorial dimensions of the Romanian parties: elections, party rules and organisations. Studia Politica: Romanian Political Science Review, 12(2), 185-210. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-445733 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC-ND Lizenz This document is made available under a CC BY-NC-ND Licence (Namensnennung-Nicht-kommerziell-Keine Bearbeitung) zur (Attribution-Non Comercial-NoDerivatives). For more Information Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.de Territorial Dimensions of the Romanian Parties 185 Territorial Dimensions of the Romanian Parties Elections, Party Rules and Organisations ALEXANDRA IONAŞCU The CEE histories have known numerous tides in instituting genuine electoral democracies. The rapid adoption of the representative rule and the myriad of new parties engaged in the electoral competition, soon after the fall of communism, were primarily conceived as trademarks in explaining political transitions. Aiming at creating closer links between the electorate and the political elites, shaping voters’ allegiance to the national political system, the post-communist electoral processes were promoting strongly fragmentised and volatile party systems1 described by the existence of blurred links with the civil society2. Acting as public utilities3 and not as chains of representation, the newly emergent parties were mainly oriented towards patronage and clientelistic practices4, neglecting the development of local implantations or the consecration of responsive political leaders. -

Romania by Laura Stefan, Dan Tapalaga and Sorin Ionita

Romania by Laura Stefan, Dan Tapalaga and Sorin Ionita Capital: Bucharest Population: 21.5 million GNI/capita: US$13,380 Source: The data above was provided by The World Bank, World Bank Indicators 2010. Nations in Transit Ratings and Averaged Scores 1999–2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 Electoral Process 2.75 3.00 3.00 2.75 2.75 2.75 2.75 2.75 2.75 2.50 2.75 Civil Society 3.00 3.00 3.00 2.75 2.50 2.25 2.25 2.25 2.25 2.50 2.50 Independent Media 3.50 3.50 3.50 3.75 3.75 4.00 4.00 3.75 3.75 3.75 4.00 Governance* 3.50 3.75 3.75 3.75 3.75 n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a National Democratic Governance n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a 3.50 3.50 3.50 3.75 3.75 4.00 Local Democratic Governance n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a 3.00 3.00 3.00 3.00 3.00 3.00 Judicial Framework and Independence 4.25 4.25 4.25 4.25 4.25 4.00 4.00 3.75 4.00 4.00 4.00 Corruption 4.25 4.50 4.75 4.50 4.50 4.25 4.25 4.00 4.00 4.00 4.00 Democracy Score 3.54 3.67 3.71 3.63 3.58 3.39 3.39 3.29 3.36 3.36 3.46 * Starting with the 2005 edition, Freedom House introduced separate analysis and ratings for national democratic governance and local democratic governance to provide readers with more detailed and nuanced analysis of these two important subjects. -

ARTICOLE DIN Publicaţii PERIODICE Cultură Anul XIX/Nr.12 2018

BIBLIOTECA NAÕIONALÅ A ROMÂNIEI BIBLIOGRAFIA NAÕIONALÅ ROMÂNÅ ARTICOLE DIN PUBLICAţII PERIODICE CULTURă anul XIX/nr.12 2018 EDITURA BIBLIOTECII NAÕIONALE A ROMÂNIEI BUCUREØTI BIBLIOTECA NAŢIONALĂ A ROMÂNIEI BIBLIOGRAFIA NAŢIONALĂ ROMÂNĂ Articole din publicaţii periodice. Cultură Bibliografie elaborată pe baza publicaţiilor din Depozitul Legal Anul XIX Nr. 12/2018 Editura Bibliotecii Naţionale a României BIBLIOGRAFIA NAŢIONALĂ ROMÂNĂ SERII ŞI PERIODICITATE Cărţi.Albume.Hărţi: bilunar Documente muzicale tipărite şi audiovizuale: anual Articole din publicaţii periodice. Cultură: lunar Publicaţii seriale: anual Românica: anual Teze de doctorat: semestrial Articole din bibliologie și știința informării: semestrial ©Copyright 2018 Toate drepturile sunt rezervate Editurii Bibliotecii Naţionale a României. Nicio parte din această lucrare nu poate fi reprodusă sub nicio formă, prin mijloc mecanic sau electronic sau stocat într-o bază de date, fără acordul prealabil, în scris, al redacţiei. Colectiv de redacţie: Roxana Pintilie Mihaela Vazzolla Anişoara Vlad Nicoleta Ştefan Florentina Cătuneanu Silvia Căpățână Corina Niculescu Monica Mioara Jichița Coperta: Constantin Aurelian Popovici ARTICOLE DIN PUBLICAŢII PERIODICE. CULTURĂ 3 Cuprins Cuprins ..................................................................................................................... 3 0 GENERALITĂȚI ............................................................................................... 6 004 Știința și tehnologia calculatoarelor. Calculatoare. Prelucrarea și -

The Romanian Double Executive and the 2012 Constitutional Crisis Vlad Perju, Boston College Law School

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School Boston College Law School From the SelectedWorks of Vlad Perju January, 2015 The Romanian Double Executive and the 2012 Constitutional Crisis Vlad Perju, Boston College Law School Available at: http://works.bepress.com/vlad_perju/54/ THE ROMANIAN DOUBLE EXECUTIVE AND THE 2012 CONSTITUTIONAL CRISIS Vlad Perju1 § 1. Introduction In the summer of 2012, Romania experienced the deepest constitutional crisis in its post- communist history. For the European Union (“EU”), which Romania joined in 2007, the crisis amplified an existential challenge posed by a turn to constitutional authoritarianism in its new member states. Coming after similar developments in Hungary, the Romanian crisis forced the “highly interdependent”2 EU to grapple with the question of how to enforce basic principles of constitutionalism within the states. That challenge would have been unthinkable even a decade earlier. In “A Grand Illusion”, an essay on Europe written in 1996, well before the Eastern expansion of the EU, Tony Judt argued that the strongest argument for such an expansion, which he otherwise did not favor, was that membership in the Union would quiet the “own internal demons” of the Eastern 3 European countries and “protect them against themselves.” It turns out, however, that 1 Associate Professor, Boston College Law School and Director, Clough Center for the Study of Constitutional Democracy. I have presented earlier versions of this paper at the ICON conference on Constitutionalism in Central and Eastern Europe at Boston College, the Montpelier Second Comparative Constitutional Law Roundtable, the International and Comparative Law Workshop at Harvard Law School and at the Center for European Studies at Harvard University.