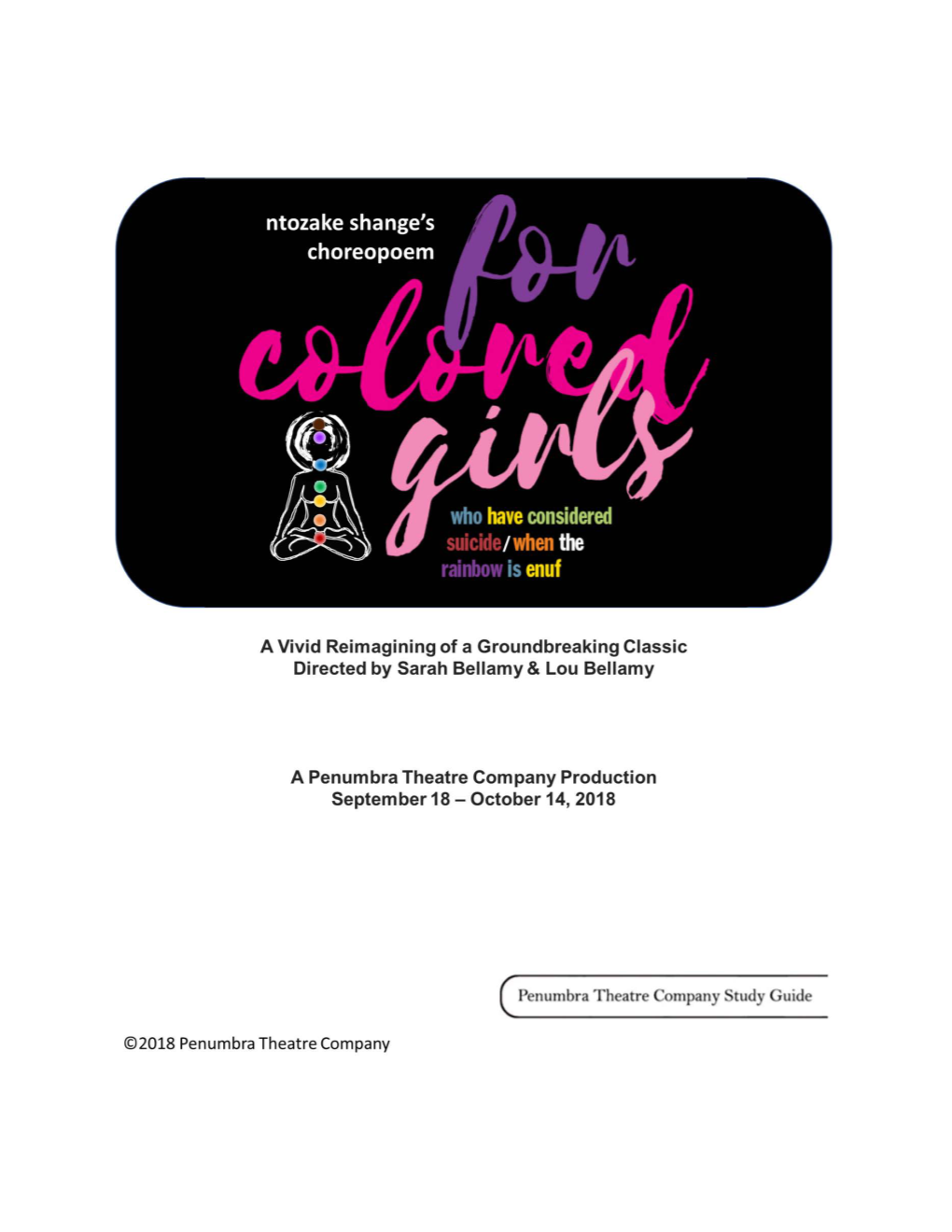

For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide/When the Rainbow Is Enuf by Ntozake Shange

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ishmael Reed Interviewed

Boxing on Paper: Ishmael Reed Interviewed by Don Starnes [email protected] http://www.donstarnes.com/dp/ Don Starnes is an award winning Director and Director of Photography with thirty years of experience shooting in amazing places with fascinating people. He has photographed a dozen features, innumerable documentaries, commercials, web series, TV shows, music and corporate videos. His work has been featured on National Geographic, Discovery Channel, Comedy Central, HBO, MTV, VH1, Speed Channel, Nerdist, and many theatrical and festival screens. Ishmael Reed [in the white shirt] in New Orleans, Louisiana, September 2016 (photo by Tennessee Reed). 284 Africology: The Journal of Pan African Studies, vol.10. no.1, March 2017 Editor’s note: Here author (novelist, essayist, poet, songwriter, editor), social activist, publisher and professor emeritus Ishmael Reed were interviewed by filmmaker Don Starnes during the 2014 University of California at Merced Black Arts Movement conference as part of an ongoing film project documenting powerful leaders of the Black Arts and Black Power Movements. Since 2014, Reed’s interview was expanded to take into account the presidency of Donald Trump. The title of this interview was supplied by this publication. Ishmael Reed (b. 1938) is the winner of the prestigious MacArthur Fellowship (genius award), the renowned L.A. Times Robert Kirsch Lifetime Achievement Award, the Lila Wallace-Reader's Digest Award, a Guggenheim Fellowship, and a Rosenthal Family Foundation Award from the National Institute for Arts and Letters. He has been nominated for a Pulitzer and finalist for two National Book Awards and is Professor Emeritus at the University of California at Berkeley (a thirty-five year presence); he has also taught at Harvard, Yale and Dartmouth. -

View Centro's Film List

About the Centro Film Collection The Centro Library and Archives houses one of the most extensive collections of films documenting the Puerto Rican experience. The collection includes documentaries, public service news programs; Hollywood produced feature films, as well as cinema films produced by the film industry in Puerto Rico. Presently we house over 500 titles, both in DVD and VHS format. Films from the collection may be borrowed, and are available for teaching, study, as well as for entertainment purposes with due consideration for copyright and intellectual property laws. Film Lending Policy Our policy requires that films be picked-up at our facility, we do not mail out. Films maybe borrowed by college professors, as well as public school teachers for classroom presentations during the school year. We also lend to student clubs and community-based organizations. For individuals conducting personal research, or for students who need to view films for class assignments, we ask that they call and make an appointment for viewing the film(s) at our facilities. Overview of collections: 366 documentary/special programs 67 feature films 11 Banco Popular programs on Puerto Rican Music 2 films (rough-cut copies) Roz Payne Archives 95 copies of WNBC Visiones programs 20 titles of WNET Realidades programs Total # of titles=559 (As of 9/2019) 1 Procedures for Borrowing Films 1. Reserve films one week in advance. 2. A maximum of 2 FILMS may be borrowed at a time. 3. Pick-up film(s) at the Centro Library and Archives with proper ID, and sign contract which specifies obligations and responsibilities while the film(s) is in your possession. -

Three Forms of Death in David Rabe's the Basic Training of Pavlo

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Honors Theses Honors College Spring 5-2019 Three Forms of Death in David Rabe’s The Basic Training of Pavlo Hummel and Sticks and Bones Sloan Garner University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/honors_theses Part of the Dramatic Literature, Criticism and Theory Commons Recommended Citation Garner, Sloan, "Three Forms of Death in David Rabe’s The Basic Training of Pavlo Hummel and Sticks and Bones" (2019). Honors Theses. 625. https://aquila.usm.edu/honors_theses/625 This Honors College Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi Three Forms of Death in David Rabe’s The Basic Training of Pavlo Hummel and Sticks and Bones By Sloan Garner A Thesis Submitted to the Honors College of The University of Southern Mississippi In Partial Fulfillment of Honors Requirements May 2019 ii Approved by Alexandra Valint, Ph.D., Thesis Advisor Associate Professor of English, Director of Graduate Studies Luis Iglesias, Ph.D. Interim Director of School of Humanities Stacy Reischman Fletcher, M.F.A. Director of School of Visual and Performing Arts Ellen Weinauer, Ph.D. Dean of Honors College iii Abstract In this thesis, I argue there are three main forms of death that progress chronologically in David Rabe’s The Basic Training of Pavlo Hummel and Sticks and Bones. -

NTOZAKE SHANGE, JAMILA WOODS, and NITTY SCOTT by Rachel O

THEORIZING BLACK WOMANHOOD IN ART: NTOZAKE SHANGE, JAMILA WOODS, AND NITTY SCOTT by Rachel O. Smith A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Purdue University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of English West Lafayette, Indiana May 2020 THE PURDUE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL STATEMENT OF COMMITTEE APPROVAL Dr. Marlo David, Chair Department of English Dr. Aparajita Sagar Department of English Dr. Paul Ryan Schneider Department of English Approved by: Dr. Dorsey Armstrong 2 This thesis is dedicated to my mother, Carol Jirik, who may not always understand why I do this work, but who supports me and loves me unconditionally anyway. 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to first thank Dr. Marlo David for her guidance and validation throughout this process. Her feedback has pushed me to investigate these ideas with more clarity and direction than I initially thought possible, and her mentorship throughout this first step in my graduate career has been invaluable. I would also like to thank the other members of my committee, Dr. Aparajita Sagar and Dr. Ryan Schneider, for helping me polish this piece of writing and for supporting me throughout this two-year program as I prepared to write this by participating in their seminars and working with them to prepare conference materials. Without these three individuals I would not have the confidence that I now have to continue on in my academic career. Additionally, I would like to thank my friends in the English Department at Purdue University and my friends back home in Minnesota who listened to my jumbled thoughts about popular culture and Black womanhood and asked me challenging questions that helped me to shape the argument that appears in this document. -

November 12, 2017

A Love/Hate Story in Black and White Directed by Lou Bellamy A Penumbra Theatre Company Production October 19 – November 12, 2017 ©2017 Penumbra Theatre Company Wedding Band Penumbra’s 2017-2018 Season: Crossing Lines A Letter from the Artistic Director, Sarah Bellamy Fifty years ago a young couple was thrust into the national spotlight because they fought for their love to be recognized. Richard and Mildred Loving, aptly named, didn’t intend to change history—they just wanted to protect their family. They took their fight to the highest court and with Loving v. The State of Virginia, the Supreme Court declared anti-miscegenation law unconstitutional. The year was 1967. We’re not far from that fight. Even today interracial couples and families are met with curiosity, scrutiny, and in this racially tense time, contempt. They represent an anxiety about a breakdown of racial hierarchy in the U.S. that goes back centuries. In 2017 we find ourselves defending progress we never imagined would be imperiled, but we also find that we are capable of reaching beyond ourselves to imagine our worlds anew. This season we explore what happens when the boundlessness of love meets the boundaries of our identities. Powerful drama and provocative conversations will inspire us to move beyond the barriers of our skin toward the beating of our hearts. Join us to celebrate the courage of those who love outside the lines, who fight to be all of who they are, an in doing so, urge us to manifest a more loving, inclusive America. ©2017 Penumbra Theatre Company 2 Wedding Band Table of Contents Introductory Material ........................................................................................................................ -

MASARYK UNIVERSITY BRNO Human Rights Expressed by Voices of the Characters in Ntozake Shange´S Plays

MASARYK UNIVERSITY BRNO FACULTY OF EDUCATION Department of English Language and Literature Human Rights Expressed by Voices of the Characters in Ntozake Shange´s Plays Bachelor Thesis Brno 2018 Supervisor: Author: Mgr. Lucie Podroužková, Ph.D. Jana Veselá, DiS. Bibliografický záznam Veselá, Jana. Základní lidská práva vyjádřena hlasy postav v divadelních hrách Ntozake Shange: bakalářská práce. Brno: Masarykova univerzita, Fakulta pedagogická, Katedra anglického jazyka a literatury, 2018. 62 s. Vedoucí bakalářské práce Mgr. Lucie Podroužková, Ph.D. Bibliography Veselá, Jana. Human Rights Expressed by Voices of the Characters in Ntozake Shange´s Plays: bachelor thesis. Brno: Masaryk University, Faculty of Education, Department of English Language and Literature, 2018. 62 pages. The supervisor of the bachelor thesis Mgr. Lucie Podroužková, Ph.D. Anotace Bakalářská práce Základní lidská práva vyjádřena hlasy postav v divadelních hrách Ntozake Shange pojednává o divadelních hrách Ntozake Shange. Práce obsahuje informace o autorce, představuje typické znaky jejích her. Cílem práce je analýza myšlenkových postojů postav v hrách For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide/When the Rainbow Is Enuf, Spell #7, A Photograph: Lovers in Motion, Boogie Woogie Landscapes a ve hře From Okra to Greens. Součástí rozboru jsou i monology či básně, které slouží také k předvádění na jevišti. Jedná se o The Love Space Demands a I Heard Eric Dolphy in His Eyes. Práce porovnává ženské i mužské kvality postav či jejich charakterové nedostatky zasazené do černošského prostředí s ohledem na kulturní rozdíly mezi černou a bílou komunitou. Závěr práce tvoří zhodnocení oblastí lidských práv, jež jsou obsaženy v názorech postav. Abstract The bachelor thesis Human Rights Expressed by Voices of the Characters in Ntozake Shange´s Plays deals with stage plays by Ntozake Shange. -

Umbra Search: African American History

Umbra Search: African American History Umbra Search African American History is a freely available widget (an element of a graphical user interface that displays) information or provides a specific way for a user to interact with an operation system or an application and search tool via umbrasearch.org that facilitates access to African American history through digitization content, community events and workshops developed by the Givens Collection of African American Literature at the University of Minnesota Libraries’ Archives and Special Collections, with Penumbra Theatre Company. The service is a response to a project dedicated to understanding the role of theater archives in documenting history. However, the scope of immediately went beyond theater and the performing arts to unite the historical artifacts and documents that represent the full depth and breadth of the African American experience—its people, places, ideas, events, movements, and inspirations in hope that this rich history will find new life and form in theater, literature, works of art, journalism, scholarship, teaching curricula, and much more. Hence the project began in 2012 with ‘Preserving the Ephemeral: An Archival Program for Theater and the Performing Arts” (https://www.lib.umn.edu/about/ephemeral/), originally conceived as The African American Theater History Project with funding from the Institute of Museum and Library Services, Preserving the Ephemeral was a collaboration between the University of Minnesota and Penumbra Theatre Company to assess the needs of the theater community, and ethnic theaters in particular, around questions of archives and historical legacy wherein over 300 theater representatives responded to a national survey in partnership with American Theatre Archive Project, and artistic directors and founders from over 60 theaters around the U.S. -

University Microfilms, a XERQ\Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan

72- 19,021 NAPRAVNIK, Charles Joseph, 1936- CONVENTIONAL AND CREATED IMAGERY IN THE LOVE POEMS OF ROBERT BROWNING. The University of Oklahoma, Ph.D. , 1972 Language and Literature, general University Microfilms, A XERQ\Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan (^Copyrighted by Charles Joseph Napravnlk 1972 THIS DISSERTATION HAS BEEN MICROFILMED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED THE UNIVERSITY OF OKIAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE CONVENTIONAL AND CREATED IMAGERY IN THE LOVE POEMS OP ROBERT BROWNING A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY CHARLES JOSEPH NAPRAVNIK Norman, Oklahoma 1972 CONVENTIONAL AND CREATED IMAGERY IN THE LOVE POEMS OF ROBERT BROWNING PROVED DISSERTATION COMMITTEE PLEASE NOTE: Some pages may have indistinct print. Filmed as received. University Microfilms, A Xerox Education Company TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION...... 1 II. BACKGROUND AND RATIONALE.................. 10 III, THE RING, THE CIRCLE, AND IMAGES OF UNITY..................................... 23 IV. IMAGES OF FLOWERS, INSECTS, AND ROSES..................................... 53 V. THE GARDEN IMAGE......................... ?8 VI. THE LANDSCAPE OF LOVE....... .. ...... 105 FOOTNOTES........................................ 126 BIBLIOGRAPHY.............. ...................... 137 iii CONVENTIONAL AND CREATED IMAGERY IN THE LOVE POEMS OP ROBERT BROWNING CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION Since the founding of The Browning Society in London in 1881, eight years before the poet*a death, the poetry of Robert -

Fd Playbill Draft 05

WHTC's New Play Development Series AMERICAN WOMEN presents a Lab production of Actors' Equity Association (AEA), founded in 1913, FREEZER DREAMS represents more than 45,000 actors and stage managers in the United States. Equity seeks to advance, promote and foster the art of live theatre as an essential component of our society. Equity negotiates wages and working conditions, providing a wide range of benefits, including health and pension plans. AEA is a member of the AFL-CIO, By Jess Foster and is affiliated with FIA, an international organization of performing arts unions. The Equity emblem is our mark of Directed by Cyndy A. Marion** excellence. www.actorsequity.org Featuring: Katie Hartman, Sarah Levine, Cynthia Shaw, Heather Lee Rogers, David Sedgwick*, and Jen Wiener Special Props/Sets: John C. Scheffler, Costumes: Derek Nye Lockwood, Lighting Design: Debra Leigh Siegel, Fight Choreography: Michael G. Chin, Assistant Director/ASM: Alanna Dorsett, Stage Management & Sound Design: Elliot Lanes, Master Electrician: Shawn Wysocki Moderated discussion led by Dramaturg Vanessa R. Bombardieri will directly follow each COMING MAY 3-19, 2013 performance Marsha Norman's Pulitzer Prize-winning 'NIGHT, MOTHER Joria Productions 260 West 36th Street, 3rd floor Sat. Nov. 17th at 1pm & 7pm, 2012 Save the Date: For WHTC's 10th Anniversary Celebration! *MemberActors’ Equity/Equity Approved Showcase Monday, January 14th, 2013 **Member SDC at The Players , Gramercy Park 6:30 p.m. - 9:00 p.m. Show Graphic by Jen Wiener/Program designed by Leslie Feffer www.whitehorsetheater.com This program was made possible in part through the sponsorship of The Field and with funding provided by WHTC sponsors Ballet, Wings Theatre Company, Michael Chekhov Theater Company, Mansfield Council for the Arts, Hackmatack Playhouse, and the COMPANY BIOS: Harry Hope Theatre. -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

The Two Gentlemen of Verona by William Shakespeare

ASF Study Materials for The Two Gentlemen of Verona by William Shakespeare Director Greta Lambert Study materials written by Set Design Rob Wolin Susan Willis, ASF Dramaturg Costume Design Elizabeth Novak [email protected] Lighting Design Tom Rodman Contact ASF at: www.asf.net Sound Design Will Burns 1.800.841-4273 1 The Two Gentlemen of Verona by William Shakespeare Welcome to The Two Gentlemen of Verona — a Tale of Friendship and Love Shakespeare knows young love—we immediately think of Romeo and Juliet and the host of romantic comedies he penned. The Characters in the Tour truism is that "the course of true love never did in Verona: run smooth," for the Bard rarely gives any of his Valentine, a young gentleman young lovers an easy time on their way to the altar. Speed, Valentine's page Challenges and hardships season the lovers— Proteus, a young gentleman, their affections are mangled, their friendships Valentine's best friend tested, their self-knowledge questioned, and Launce, his servant their behavior turned unrecognizable even to Crab, Launce's dog, a mutt themselves. Why? Because they are young Julia, the girl Proteus loves and in love, so both inside and out things seem Lucetta, her maid confusing, uncertain, and unsettling. Antonio, Proteus's father In this play, Shakespeare sets his scene in fair Verona, or at least starts it there. Verona in Milan: is home to the two gents who now must leave The Duke, Silvia's father and make their way in the larger outside world Silvia, Valentine's beloved of the Milanese court, where ambition and love Sir Thurio, a wealthy nobleman will entangle and complicate their lives—and in love with Silvia the lives of the young women who love them. -

Race in Hollywood: Quantifying the Effect of Race on Movie Performance

Race in Hollywood: Quantifying the Effect of Race on Movie Performance Kaden Lee Brown University 20 December 2014 Abstract I. Introduction This study investigates the effect of a movie’s racial The underrepresentation of minorities in Hollywood composition on three aspects of its performance: ticket films has long been an issue of social discussion and sales, critical reception, and audience satisfaction. Movies discontent. According to the Census Bureau, minorities featuring minority actors are classified as either composed 37.4% of the U.S. population in 2013, up ‘nonwhite films’ or ‘black films,’ with black films defined from 32.6% in 2004.3 Despite this, a study from USC’s as movies featuring predominantly black actors with Media, Diversity, & Social Change Initiative found that white actors playing peripheral roles. After controlling among 600 popular films, only 25.9% of speaking for various production, distribution, and industry factors, characters were from minority groups (Smith, Choueiti the study finds no statistically significant differences & Pieper 2013). Minorities are even more between films starring white and nonwhite leading actors underrepresented in top roles. Only 15.5% of 1,070 in all three aspects of movie performance. In contrast, movies released from 2004-2013 featured a minority black films outperform in estimated ticket sales by actor in the leading role. almost 40% and earn 5-6 more points on Metacritic’s Directors and production studios have often been 100-point Metascore, a composite score of various movie criticized for ‘whitewashing’ major films. In December critics’ reviews. 1 However, the black film factor reduces 2014, director Ridley Scott faced scrutiny for his movie the film’s Internet Movie Database (IMDb) user rating 2 by 0.6 points out of a scale of 10.