California State University, Northridge Training Parents in Reading Remediation Techniques

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Inventory of the Jay Williams Collection #227

The Inventory of the Jay Williams Collection #227 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center ,. .·~ All Mary Renault letters I·.' RESTRICTED ,' ' ~- __j Cassette tapes of interviews, for Stage Left, Boxes 24,~5 REJSTRICTED .Stol148 by WUJ.uma Box 1 ~i~ ~ace, toi: :tP,e, Soul.; • ty:peaeript with holograph annotation# • 4 pa.sea Aluwn.U8 !!!l_,. lookil like carbon, 130 annotation& - 12 J.'Glilll• l3asil The Rel~ ~ tn,eaor!i>tvith8llll0t.tions .. 5 pages • earl.1 OCfW tyi,esoript - , J.1881&• • later copy ~. ~u,c far1 • 'typeaoript vith holograph annotatione • 3 lJ8811• • c pped th t ~• l.frt;t;.er from Oxford Uniwrsity P.t-a• an4 l page typescnpt 1dtb ~tiona • Theio Behold A ._.( ln1 Mi~ Swl.JA (In] ) ~ ••·:· 2!!!. .utif'ul: ~ .. aecepted for publ:lcation by ~:wm,' • Mtg., l'Onto, ----------• ~oript with holograph annotati<).n&t • 21 paae,• · ~ Beetle • ~script witb holograph annotat1oms • 10 pas$• (J.•}J!a:rJlh~ Presen~ (Jay Williams aud. lrving Wer#t.:Ln) • 1;)1lGIOript 'lr.l,th . ·. holograph Anl30tations • 19 :pa.sea · . • (J.a.~ Boa.t (Will~uu• and In1ng Werstein) · . · ~so:ript Yitb holograph annotations• 17 ~ ,:. c. ""CArbon C<:rf!:f ot type1cript .. annotat1oll8 • 17 ~• (~•-•)l3oth 1"t Q!_ ~ Ol'aul¥l (W:Ul:Lanm and Ir"ri.nS l'-ratein) • ~cr1P' . .·. With lml,¢t&tioM -+t 22 ~• · . ,· ~ ~:t~. Over i'he Itiver rl~ • looks 11ke carl>on rith holoa:ra»h a.n.i. I • notitions ...T ~a :f'airy We tor co.lle~ otuaenti) . i t~ 1'¼!. ~ter, S;e!Siea .. looka like carbon • 9 ~" ,•' ,'.'' ~!s 1'hee ~ State~ )l3.ns1ona • type10,:;tpt .i· 1 ~• !;t l3ree.d Alone - typescript rith bologrm:ph azi.notationa • l3 p,.sea t:arsq;els J\e~!!!'t ~ World • ~ypescript w1:tll, b.olo£r$ph au.otationl • ~ . -

WHAT TEACHERS READ to PUPILS in the MIDDLE GRADES. the Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1969 Educati

This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 69-15,971 TOM, Chow Loy, 1918- WHAT TEACHERS READ TO PUPILS IN THE MIDDLE GRADES. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1969 Education, general University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan Copyright by Chow Loy Tom 1969 WHAT TEACHERS HEAD TO PUPILS IN THE MIDDLE GRADES DISSERTATION Presented in Partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University 3y Chov/Loy Tom, Ed.B., 3.S., M.S. ****** The Ohio State University 1969 Approved by Adviser College of Education VITA September 9» 1918 B o m - Hilo, Hav/aii. 194-1* ... Ed.B., University of Hawaii, Honolulu, Hawaii. 1941.......... Five-Year Diploma, University of Hawaii. 1942-1943...... librarian: Honokaa High and Elementary School, Honokaa, Hav/aii. 1943.......... B.S., with honors, University of Illinois, Urbana, Illinois. 1945-1946 ...... librarian: Reference and Young Adult Depart ments, Allentown Free library, Allentown, Pennsylvania. 1946-1947 ...... librarian: Robert L. Stevenson Intermediate School, Honolulu, Hawaii. 1947-1948... ... librarian: Lanakila Elementary School, Honolulu, Hav/aii. 1948-1949. ... librarian: Benjamin Parker High and Elementary School, Kaneohe, Hav/aii. 1949-195 2..... librarian: Kaimuki High School, 1953-1956...... Honolulu, Hav/aii. 1957-1959...... 1953......... M.S., University of Illinois, Urbana, Illinois. 1956-1957...... Acting librarian: University High School; Instructor: College of Education, University of Illinois, Urbana, Illinois. 1959-1961...... Supervisor & librarian: University High School; Instructor: College of Education, University of Hav/aii, Honolulu, Hav/aii. iii 1961-1965...... Assistant Professor: Coordinator of and teacher in the Library Science Education Program, University of Hav/aii. -

Family Reading Booklist

FAMILY READING BOOKLIST Biblical evaluations of wholesome books for your children and family by David E. Pratte www.gospelway.com/family Family Reading Booklist © Copyright, David E. Pratte, 1994, 2013 Introduction One of the greatest needs for families today is wholesome entertainment. Television, movies, music, etc., are generally filled with immorality, violence, and just plain depression and me- diocrity. Entertainment, like other areas of a Christian’s life, ought to encourage and challenge him to be a better person (Phil 4:8). Most families could use help in finding that kind of entertainment. One excellent source of entertainment can be good books; but many books, especially those written more recently, are also filled with immorality. How do we find good books? The purpose of this booklist is to review some good books I have come across that you may be interested in having your family read. Some of these may be considered “classics,” others are books I just happened across. You may have some difficulty finding some of the books, but you should have enough information here that your library can obtain them by interlibrary loan. I have looked for wholesome qualities in the books such as: faith in God, family devotion, honesty, hard work, courage, helpfulness to others, etc. I have also sought to avoid negative qualities such as sexual explicitness, profanity, violence, drinking alcohol, smoking, gambling, evolution, irreverence toward God, and other forms of ungodliness. I have tried to note when I found such qualities in books, good or bad. Some problems I have considered serious enough to eliminate a book from the list, but in other cases I have kept the book on the list but warned you about a problem. -

Open a World of Possible Ebook

PEN OA WORLD OF POssIBLE Real Stories About the Joy and Power of Reading Edited by Lois Bridges Foreword by Richard Robinson New York • Toronto • London • Auckland • Sydney Mexico City • New Delhi • Hong Kong • Buenos Aires DEDICATION For all children, and for all who love and inspire them— a world of possible awaits in the pages of a book. And for our beloved friend, Walter Dean Myers (1937–2014), who related reading to life itself: “Once I began to read, I began to exist.” b Credit for Charles M. Blow (p. 40): From The New York Times, January 23 © 2014 The New York Times. All rights reserved. Used by permission and protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States. The printing, copying, redistribution, or retransmission of this Content without written permission is prohibited. Credit for Frank Bruni (p. 218): From The New York Times, May 13 © 2014 The New York Times. All rights reserved. Used by permission and protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States. The printing, copying, redistribution, or retransmission of this Content without written permission is prohibited. Scholastic grants teachers permission to photocopy the reproducible pages from this book for classroom use. No other part of this publication may be reproduced in whole or in part, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without permission of the publisher. For information regarding permission, write to Scholastic Inc., 557 Broadway, New York, NY 10012. Cover Designer: Charles Kreloff Editor: Lois Bridges Copy/Production Editor: Danny Miller Interior Designer: Sarah Morrow Compilation © 2014 Scholastic Inc. -

Some Approaches to Teaching the Speculative Literature of Science Fiction and the Supernatural

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 128 788 CS 202 768 TITLE Far Out: Some Approaches to Teaching the Speculative Literature of Science Fiction and the Supernatural. INSTITUTION Los Angeles City Schools, Calif. Div. of Instructional Planning and Services. PUB DATE 74 NOTE 121p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.83 HC-$6.01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Behavioral Objectives; Bibliographies; Curriculum Guides; Fantasy; *Fiction; Films; *Literature Appreciation; *Science Fiction; Secondary Education; Short Courses ABSTRACT This curriculum guide contains course descriptions (for minicourses and semester-long courses), outlines, and class projects for teaching science fiction and the supernatural in junior and senior high schools. The eight course descriptions include objectives, methods, activities, and resources and materials. Lists of science fiction books and films are appended. (JR) *********************************************************************** * Documents acquired by ERIC include many informal unpublished * *materials not available from other sources. ERIC akes every effort* *to obtain the best copy available. Nevertheless, items of marginal * *reproducibility are often encountered and this affects the quality * *of the microfiche and hardcopy reproductions ERIC makes available * *via the ERIC Document Reproduction Service (EDRS). EDRS is not * *responsible for the quality of the original document. Reproductions* *supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original. * *********************************************************************** ,B U S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION WELFARE op . NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF co EDUCATION TmIS DOCUMENT mAS BEEN REPRO- r-- DUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIGIN- oo ATING IT POINTS OF viEw oq OPINIONS \.1 STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRE c SENT OFFICIAL NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF v-4 EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY I Ca FAR OUT 11J Some Approaches to Teaching The Speculative Literature of Science Fiction and the Supernatural ,rqu Los Angeles City Schools, Instructional Planning Division, Publication No. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Danny Dunn Time Traveler by Jay Williams Danny Dunn Time Traveler by Jay Williams

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Danny Dunn Time Traveler by Jay Williams Danny Dunn Time Traveler by Jay Williams. THE DANNY DUNN SERIES By Jay Williams and Raymond Abrashkin. DANNY DUNN AND THE ANTI-GRAVITY PAINT -- " A daydreaming youth accidently launches the first manned flight to outer space. " -- " Danny Dunn and his friend Professor Bullfinch accidentally develop a liquid that defies the power of gravity ." -- illustrated by Ezra Jack Keats. 1956. 1972. McGraw-Hill. Weekly Reader Book Club. Whittlesey House. Brockhampton Press. Scholastic. Pocket Books. Danny Dunn Time Traveler by Jay Williams. Danny Dunn and the Swamp Monster is the 12th book in the series, and was published in 1971. The plot revolves around the search for a mysterious creature, the Lau, that lives in the swamps of northeastern Africa. Given the locations mentioned, it appears to be somewhere in what is now South Sudan, but the final place names do not appear to be known to Google Maps, and so the exact location remains a mystery, as it should be. Of course, it wouldn't be a Danny Dunn story without a cool science MacGuffin, and this episode's contribution is a room temperature superconductor that Professor Bulfinch cooks up in his lab. This time the accident that creates something that scientists have spent decades and millions of dollars searching for, is as much the Professor's fault as Danny's. Simply overcook a pot of polymer on the stove and then give it an electrical shock, and you have something that would change the world as we know it . -

Library Book List by Author

Author Last Name Author First Name Title Handmade in the Northern Forest Guide Skechers Paul Bunyan Lemony Snicket: The Unauthorized Autobiography Abbott Tony Postcard Acheson Dean President at the Creation Adams Alice Medicine Men Adams Douglas Mostly Harmless Adams Douglas Life, The Universe and Everything Adams Douglas Dirk Gently's Holistic Detective Agency Adams Douglas Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy Adams Douglas Restaurant at the End of the Universe Adams Book of Abigail and John Adams Douglas Long Dark Tea-Time of the Soul Agatston, M. Arthur South Beach Diet Agatston, M.C. Arthur South Beach Diet Agnew Spiro T. Go Quietly or Else Ahlberg Allan Little Cat Baby Aiken Joan Wolves of Willoughby Chase Aiken Joan Night Birds on Nantucket Albom Mitch Five People You Meet in Heaven Albright Barbara Natural Knitter, The Alder Ken Measure of all Things Alexander Martha Nobody Asked me if I Wanted a Baby Sister Alexander Lloyd High King Alexander Martha We Never Go to do Anything Alexander Martha No Ducks in our Bathtub Alexandra Belinda Wild Lavender Allard Harry Its So Nice to Have a Wolf Around the House Allen Tim Don't Stand Too Close To A Naked Man Allen Mea Weeds Almond David Skellig Almond David Kits Wilderness Almond David Fire Eaters Alsop Joseph W. I've Seen the Best of it - Memories Ambler Eric Light of Day Ambler Eric Journey Into Fear Ambrose Stephen E. Comrades Ambrose Stephen E. Comrades Ambrus Victor A Country Wedding American Girl Very Funny, Elizabeth American Heart Association Low-Salt Cookbook Ames Mildred Silken Tie Ames Mildred Cassandra - Jamie Ames Mildred Silver Link Amory Cleveland Cat who Came for Christmas, The Amory Cleveland Cat Who Came for Shristmas, The Amoss Berthe Secret Lives Andersen Hans Christian Wild Swans Andersen Hans Christian Nightingale Andersen Hans Christian Steadfast Tin Soldier Anderson Lucia Smallest Life Around Us Anderson Karen Why Cats do That Anderson Mary Rise and Fall of a Teenage Wacko Anderson M. -

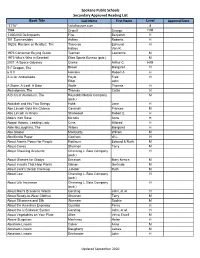

Spokane Public Schools Secondary Approved Reading List

Spokane Public Schools Secondary Approved Reading List Book Title Last Name First Name Level Approval Date "1776" kidsdiscover.com 8 1984 Orwell George H/M 1,000,000 Delinquents Fine Benjamin H 101 SummerJobs Ashley Roberta H 1920s: Rhetoric or Reality?, The Traverso Edmund H Halsey Van R. 1973 Consumer Buying Guide Teeman Lawrence M 1973 Who’s Who in Baseball Elias Sports Bureau (pub.) M 2001: A Space Odyssey Clarke Arthur C. H/M 51st Dragon, The Brown Margaret H 6 X 8 Heinlein Robert A. H A is for Andromeda Hoyle Fred H Elliot John A Stone, A Leaf, A Door Wolfe Thomas H Abandoners, The Thomas Cottle H A-B-Cs of Aluminum, The Reynolds Metals Company M (pub.) Abdullah and His Two Strings Hukk Jane H Abe Lincoln Gets His Chance Cavanah Frances M Abe Lincoln in Illinois Sherwood Robert E. H Abie's Irish Rose Nichols Anne H Abigail Adams, Leading Lady Criss Mildred H Able McLaughlins, The Wilson Margaret H Abo Simbel MacQuitty William M Abolitionist Paper Garrison W.L. H About Atomic Power for People Rodlauer Edward & Ruth M About Caves Shannon Terry M About Checking Accounts Channing L. Bete Company H (pub.) About Glasses for Gladys Ericsson Mary Kentra M About Insects That Help Plants Gibson Gertrude M About Jack’s Dental Checkup Jubelier Ruth M About Law Channing L. Bete Company H (pub.) About Life Insurance Channing L. Bete Company H (pub.) About Man's Economic Wants Gersting John, et al. H About Ready-to-Wear Clothes Shannon Terry M About Silkworms and Silk Wormser Sophie M About the American Economy Guyston Percy H About the U.S.Market System Gersting John, et al. -

Danny Dunn 4

Danny Dunn and the Weather Machine Jay Williams and Raymond Abrashkin All characters in this book are entirely fictitious. The Fourth Danny Dunn Adventures Copyright ©1959. renewed 1977 by Jay Williams and Raymond Abrashkin. Illustrated by Ezra Jack Keats All rights in this book are reserved. This book may not be used for dramatic, motion-, or talking- picture purposes without written authorization from the holder of these rights. Nor may the book or parts thereof be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without permission in writing, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. This book is for Michele, Michael, Timmy and Brett Acknowledgments We are deeply grateful to Nathan Barrey, meteorologist at Bridgeport Airport (Conn.); Patrick Walsh, meteorologist in the New York City Weather Bureau; Julius Schwartz, Consultant in Science, Bureau of Curriculum Research, New York City Schools; Stanley Koencko, president of the Danbury (Conn.) School of Aeronautics; and Louis Huyber, all of whom assisted greatly in the preparation of this book, with technical advice and information. We are also grateful to Herman Schneider for permission to describe materials from his book Everyday Weather and How It Works (McGraw-Hill, 1951). 2 3 4 Chapter One Something from the Sky Two boys and a pretty girl, wearing swimming suits and with towels around their necks, stood in the shade of the woods. The blazing August sunlight was filtered and broken by the leaves which hung limp and dusty overhead. “Gee, it’s dry,” said Irene Miller, shaking her glossy, brown pony-tail out of the way. -

Limelight Vol.3 No.5 September-October 1989

F p , . .rlN LIGHT M Sift IE .2 q EDISON TWP, PUBjlIC LIBRARY NEWSLETTER £5 ir x r x o n n c r r r r L~xcQ~.rx~i~i~ri:r-r ; r r Volume 3, No. 5, September-October 1989 Our doors are open! Beginning October 1, the Edison Township Public Library will be participating in "Open Borrowing". This program is based upon an agreement between LINX, Union Middlesex Regional Library Cooperative, Region IV, Inc. and libraries that wish to follow the "Statement of Procedures, Terms and Conditions Between LINX and Participating Libraries". Listed below are the public libraries that are currently participating in open borrowing. They have agreed to lend materials to all residents of the region living in a community that has a public library that meets all New Jersey State Aid requirements. Berkeley Height# Garwood North Brunswick Milltown Spotewood Clark Highland Park Old Bridge Mountainside Springfield Cranbury Hillside Perth Aaboy New Providence Summit Cranford Janeeburg Plscataway Roselle Park Onion Dunellen Kenilworth Plainfield Scotch Plains Westfield Edison Linden Plalnsboro South Aaboy Woodbrldge Elizabeth Metuchen Rahway South Brunswick Psnwood Middlesex Roselle South River Isn’t it time YOU joined?! Our FRIENDS OF THE LIBRARY membership drive is now in full swing. Annual fees are payable each September. An application form is attached to this newsletter. More are available at the Circulation Desk. Our next general meeting will take place on TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 19, 7:30 PM at the Main Library. We will discuss forthcoming projects and election of new officers for 1990. We really need more participation at our meetings, so please mark your calendar and come join us! Our FRIENDS will be represented at Edison'-s "Fall Festival of Fireworks" on September 23. -

Danny Dunn on a Desert Island Jay Williams, Raymond Abrashkin

Danny Dunn on a Desert Island, 1957, Jay Williams, Raymond Abrashkin, 0140308776, 9780140308778, lPenguin Books, Limited, 1957 DOWNLOAD http://bit.ly/1qqm3X3 http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?search=Danny+Dunn+on+a+Desert+Island DOWNLOAD http://fb.me/2SFDpARyw http://www.jstor.org/stable/21126832428665 http://bit.ly/1sZcPI0 Danny Dunn and the homework machine , Jay Williams, 1958, Fiction, 122 pages. In the 1950s it was unusual to have access to a computer. Danny gets his mother and his teacher upset when he uses one.. Danny Dunn, scientific detective , Jay Williams, Raymond Abrashkin, Paul Sagsoorian, 1975, Juvenile Fiction, 172 pages. Danny Dunn tries to track down the missing manager of the local department store with the aid of a bloodhound robot.. Homer Price , Robert McCloskey, 1943, Juvenile Fiction, 149 pages. Six episodes in the life of Homer Price including one in which he and his pet skunk capture four bandits and another about a donut machine on the rampage.. Shipwreck , Gordon Korman, 2001, Juvenile Fiction, 144 pages. Follows a group of six kids stranded on a deserted island as they embark on a quest for survival that tests their limits.. Whistle for Willie , Ezra Jack Keats, Jan 1, 1964, Juvenile Fiction, 33 pages. Little Peter tries very hard to learn how to whistle for his dog. Island Trilogy, Volume 1 , Gordon Korman, 2006, Juvenile Nonfiction, 416 pages. The popular trilogy follows a group of six children stranded on a deserted island as they embark on a quest for survival that tests their limits.. Mutiny on the Bounty , Charles Nordhoff, 1989, Fiction, 379 pages.