Symbolic Identity and the Cultural Memory of Saints

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Large Castles and Large War Machines In

Large castles and large war machines in Denmark and the Baltic around 1200: an early military revolution? Autor(es): Jensen, Kurt Villads Publicado por: Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra URL persistente: URI:http://hdl.handle.net/10316.2/41536 DOI: DOI:https://doi.org/10.14195/2183-8925_30_11 Accessed : 5-Oct-2021 17:35:20 A navegação consulta e descarregamento dos títulos inseridos nas Bibliotecas Digitais UC Digitalis, UC Pombalina e UC Impactum, pressupõem a aceitação plena e sem reservas dos Termos e Condições de Uso destas Bibliotecas Digitais, disponíveis em https://digitalis.uc.pt/pt-pt/termos. Conforme exposto nos referidos Termos e Condições de Uso, o descarregamento de títulos de acesso restrito requer uma licença válida de autorização devendo o utilizador aceder ao(s) documento(s) a partir de um endereço de IP da instituição detentora da supramencionada licença. Ao utilizador é apenas permitido o descarregamento para uso pessoal, pelo que o emprego do(s) título(s) descarregado(s) para outro fim, designadamente comercial, carece de autorização do respetivo autor ou editor da obra. Na medida em que todas as obras da UC Digitalis se encontram protegidas pelo Código do Direito de Autor e Direitos Conexos e demais legislação aplicável, toda a cópia, parcial ou total, deste documento, nos casos em que é legalmente admitida, deverá conter ou fazer-se acompanhar por este aviso. impactum.uc.pt digitalis.uc.pt Kurt Villads Jensen * Revista de Historia das Ideias Vol. 30 (2009) LARGE CASTLES AND LARGE WAR MACHINES IN DENMARK AND THE BALTIC AROUND 1200 - AN EARLY MILITARY REVOLUTION? In 1989, the first modern replica in Denmark of a medieval trebuchet was built on the open shore near the city of Nykobing Falster during the commemoration of the 700th anniversary of the granting of the city's charter, and archaeologists and interested amateurs began shooting stones out into the water of the sound between the islands of Lolland and Falster. -

Russian Viking and Royal Ancestry

GRANHOLM GENEALOGY RUSSIAN/VIKING ANCESTRY Direct Lineage from: Rurik Ruler of Kievan Rus to: Lars Erik Granholm 1 Rurik Ruler of Kievan Rus b. 830 d. 879 m. Efenda (Edvina) Novgorod m. ABT 876 b. ABT 850 2 Igor Grand Prince of Kiev b. ABT 835 Kiev,Ukraine,Russia d. 945 Kiev,Ukraine,Russia m. Olga Prekrasa of Kiev b. ABT 890 d. 11 Jul 969 Kiev 3 Sviatoslav I Grand Prince of Kiev b. ABT 942 d. MAR 972 m. Malusha of Lybeck b. ABT 944 4 Vladimir I the Great Grand Prince of Kiev b. 960 Kiev, Ukraine d. 15 Jul 1015 Berestovo, Kiev m. Rogneda Princess of Polotsk b. 962 Polotsk, Byelorussia d. 1002 [daughter of Ragnvald Olafsson Count of Polatsk] m. Kunosdotter Countess of Oehningen [Child of Vladimir I the Great Grand Prince of Kiev and Rogneda Princess of Polotsk] 5 Yaroslav I the Wise Grand Duke of Kiew b. 978 Kiev d. 20 Feb 1054 Kiev m. Ingegerd Olofsdotter Princess of Sweden m. 1019 Russia b. 1001 Sigtuna, Sweden d. 10 Feb 1050 [daughter of Olof Skötkonung King of Sweden and Estrid (Ingerid) Princess of Sweden] 6 Vsevolod I Yaroslavich Grand Prince of Kiev b. 1030 d. 13 Apr 1093 m. Irene Maria Princess of Byzantium b. ABT 1032 Konstantinopel, Turkey d. NOV 1067 [daughter of Constantine IX Emperor of Byzantium and Sclerina Empress of Byzantium] 7 Vladimir II "Monomach" Grand Duke of Kiev b. 1053 d. 19 May 1125 m. Gytha Haraldsdotter Princess of England m. 1074 b. ABT 1053 d. 1 May 1107 [daughter of Harold II Godwinson King of England and Ealdgyth Swan-neck] m. -

Heineman Royal Ancestors Medieval Europe

HERALDRYand BIOGRAPHIES of the HEINEMAN ROYAL ANCESTORS of MEDIEVAL EUROPE HERALDRY and BIOGRAPHIES of the HEINEMAN ROYAL ANCESTORS of MEDIEVAL EUROPE INTRODUCTION After producing numerous editions and revisions of the Another way in which the royal house of a given country familiy genealogy report and subsequent support may change is when a foreign prince is invited to fill a documents the lineage to numerous royal ancestors of vacant throne or a next-of-kin from a foreign house Europe although evident to me as the author was not clear succeeds. This occurred with the death of childless Queen to the readers. The family journal format used in the Anne of the House of Stuart: she was succeeded by a reports, while comprehensive and the most popular form prince of the House of Hanover who was her nearest for publishing genealogy can be confusing to individuals Protestant relative. wishing to trace a direct ancestral line of descent. Not everyone wants a report encumbered with the names of Unlike all Europeans, most of the world's Royal Families every child born to the most distant of family lines. do not really have family names and those that have adopted them rarely use them. They are referred to A Royal House or Dynasty is a sort of family name used instead by their titles, often related to an area ruled or by royalty. It generally represents the members of a family once ruled by that family. The name of a Royal House is in various senior and junior or cadet branches, who are not a surname; it just a convenient way of dynastic loosely related but not necessarily of the same immediate identification of individuals. -

Jezierski & Hermanson.Indd

Imagined Communities on the Baltic Rim, from the Eleventh to Fifteenth Centuries Amsterdam University Press Crossing Boundaries Turku Medieval and Early Modern Studies The series from the Turku Centre for Medieval and Early Modern Studies (TUCEMEMS) publishes monographs and collective volumes placed at the intersection of disciplinary boundaries, introducing fresh connections between established fijields of study. The series especially welcomes research combining or juxtaposing diffferent kinds of primary sources and new methodological solutions to deal with problems presented by them. Encouraged themes and approaches include, but are not limited to, identity formation in medieval/early modern communities, and the analysis of texts and other cultural products as a communicative process comprising shared symbols and meanings. Series Editor Matti Peikola, University of Turku, Finland Amsterdam University Press Imagined Communities on the Baltic Rim, from the Eleventh to Fifteenth Centuries Edited by Wojtek Jezierski and Lars Hermanson Amsterdam University Press Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: St. Henry and St. Eric arriving to Finland on the ‘First Finnish Crusade’. Fragment of the fijifteenth-centtury sarcophagus of St. Henry in the church of Nousiainen, Finland Photograph: Kirsi Salonen Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout Amsterdam University Press English-language titles are distributed in the US and Canada by the University of Chicago Press. isbn 978 90 8964 983 6 e-isbn 978 90 4852 899 8 (pdf) doi 10.5117/9789089649836 nur 684 © Wojtek Jezierski & Lars Hermanson / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2016 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. -

Ritual and History

MIRATOR 11:1/2010 1 Ritual and History: Pagan Rites in the Story of the Princess’ Revenge (the Russian Primary Chronicle, under 945–946) 1 Aleksandr Koptev Introduction The Kievan prince Igor is known to have been murdered by tribesmen of the tributary Drevljans during a journey he made to their country with the purpose of collecting the tribute. The case is described in the Primary Chronicle under the year 945: 6453 (945). In this year, Igor’s retinue said to him, ‘The servants of Sveinald are adorned with weapons and fine raiment, but we are naked. Go forth with us, oh Prince, after tribute, that both you and we may profit thereby’. Igor´ heeded their words, and he attacked Dereva in search of tribute. He sought to increase the previous tribute and collected it by violence from the people with the assistance of his followers. After thus gathering the tribute, he returned to his city. On his homeward way, he said to his followers, after some reflection, ‘Go forward with the tribute. I shall turn back, and rejoin you later’. He dismissed his retainers on their journey homeward, but being desirous of still greater booty he returned on his tracks with a few of his followers. The Derevlians heard that he was again approaching, and consulted with Mal, their prince, saying, ‘If a wolf comes among the sheep, he will take away the whole flock one by one, unless he be killed. If we do not thus kill him now, he will destroy us all’. They 1 The article is based on my paper ‘Water and Fire as the Road to the Mythic Other World: Princess Olga and the Murdered Ambassadors in the Russian Primary Chronicle, under 945’ delivered at the Septième Colloque International d’anthropologie du monde indo-européen et de mythologie comparée “Routes et parcours mythiques: des textes à l’archéologie”, Louvain-la-Neuve, March 19–21, 2009. -

Slavic Raid on Konungahella

CM 2014 ombrukket3.qxp_CM 30.04.15 15.46 Side 6 Slavic Raid on Konungahella ROMAN ZAROFF The article explores the naval raid of the Slavic forces on the coastal norwegian port set - tlement of Konungahella in the mid 1130s. The paper analyses the raid in the context of regional politics and from the perspective of Baltic Slavs. It also encompasses the wider political context of contemporary imperial and Polish politics. It addresses the issue of the timing of the raid, participation of other than Pomeranian Slavs, and the reasons why it took place. It focuses on the reasons behind the raid which are surrounded by contro - versy and various interpretations. The paper postulates an alternative explanation to the politically motivated explanations previously accepted. One of the least known and researched historical events in Scandinavian mediaeval history appears to be the Slavic ride and plunder of the important norwegian port and settlement of Kungahälla-Konungahella 1, that took place around 1135/1136. Be - fore we analyse the reasons, causes and implication of this raid, we will concentrate on some background issues including a short description of the expedition and assault on Konungahella. Sources Regretfully our knowledge about this event comes solely from a single historical source, that being Saga of Magnus the Blind and of Harald Gille by Snorri Sturluson. he was an Icelander who was born in 1179 and died in 1249. The Saga of Magnus the Blind and of Harald Gille is part of a larger work known as Heimskringla – a saga or history of the kings of norway. -

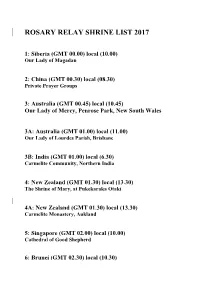

Rosary Relay Shrine List 2017

ROSARY RELAY SHRINE LIST 2017 1: Siberia (GMT 00.00) local (10.00) Our Lady of Magadan 2: China (GMT 00.30) local (08.30) Private Prayer Groups 3: Australia (GMT 00.45) local (10.45) Our Lady of Mercy, Penrose Park, New South Wales 3A: Australia (GMT 01.00) local (11.00) Our Lady of Lourdes Parish, Brisbane 3B: India (GMT 01.00) local (6.30) Carmelite Community, Northern India 4: New Zealand (GMT 01.30) local (13.30) The Shrine of Mary, at Pukekaraka Otaki 4A: New Zealand (GMT 01.30) local (13.30) Carmelite Monastery, Aukland 5: Singapore (GMT 02.00) local (10.00) Cathedral of Good Shepherd 6: Brunei (GMT 02.30) local (10.30) Church of Our Lady’s Assumption 6A: Vietnam (GMT 02.45) local (09.45) Our Lady of La Vang 7: Philippines (GMT 03.00) local (11.00). The National Shrine of Our Lady of Mount Carmel Parish, New Manila, Quezon City 8: Philippines (GMT 03.30) local (11.30) Shrine of the Immaculate Conception, Manila 9: Philippines (GMT 04.00) local (12.00) Our Lady of Manaoag 10: Sri Lanka (GMT 04.30) local (10.00) Shrine of Our Lady of Matara 11: India (GMT 05.00) local (10.30) Shrine of Our Lady of Health, Velankanni 12: Malta (GMT 05.30) local (07.30) Our Lady of Mellieha 13: UAE (GMT 06.00) local (10.00) The Church of St Mary, Dubai 14: Lebanon (GMT 06.30) local (09.30) Our Lady of Lebanon. Harissa 15: Holy Land (GMT 07.00) local (10.00) International Center of Mary of Nazareth. -

Life and Cult of Cnut the Holy the First Royal Saint of Denmark

Life and cult of Cnut the Holy The first royal saint of Denmark Edited by: Steffen Hope, Mikael Manøe Bjerregaard, Anne Hedeager Krag & Mads Runge Life and cult of Cnut the Holy The first royal saint of Denmark Life and cult of Cnut the Holy The first royal saint of Denmark Report from an interdisciplinary research seminar in Odense. November 6th to 7th 2017 Edited by: Steffen Hope, Mikael Manøe Bjerregaard, Anne Hedeager Krag & Mads Runge Kulturhistoriske studier i centralitet – Archaeological and Historical Studies in Centrality, vol. 4, 2019 Forskningscenter Centrum – Odense Bys Museer Syddansk Univeristetsforlag/University Press of Southern Denmark Report from an interdisciplinary research seminar in Odense. November 6th to 7th 2017 Published by Forskningscenter Centrum – Odense City Museums – University Press of Southern Denmark ISBN: 9788790267353 © The editors and the respective authors Editors: Steffen Hope, Mikael Manøe Bjerregaard, Anne Hedeager Krag & Mads Runge Graphic design: Bjørn Koch Klausen Frontcover: Detail from a St Oswald reliquary in the Hildesheim Cathedral Museum, c. 1185-89. © Dommuseum Hildesheim. Photo: Florian Monheim, 2016. Backcover: Reliquary containing the reamains of St Cnut in the crypt of St Cnut’s Church. Photo: Peter Helles Eriksen, 2017. Distribution: Odense City Museums Overgade 48 DK-5000 Odense C [email protected] www.museum.odense.dk University Press of Southern Denmark Campusvej 55 DK-5230 Odense M [email protected] www.universitypress.dk 4 Content Contributors ...........................................................................................................................................6 -

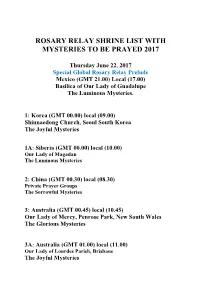

Rosary Relay Shrine List with Mysteries to Be Prayed 2017

ROSARY RELAY SHRINE LIST WITH MYSTERIES TO BE PRAYED 2017 Thursday June 22, 2017 Special Global Rosary Relay Prelude Mexico (GMT 21.00) Local (17.00) Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe The Luminous Mysteries. 1: Korea (GMT 00.00) local (09.00) Shinnaedong Church, Seoul South Korea The Joyful Mysteries 1A: Siberia (GMT 00.00) local (10.00) Our Lady of Magadan The Luminous Mysteries 2: China (GMT 00.30) local (08.30) Private Prayer Groups The Sorrowful Mysteries 3: Australia (GMT 00.45) local (10.45) Our Lady of Mercy, Penrose Park, New South Wales The Glorious Mysteries 3A: Australia (GMT 01.00) local (11.00) Our Lady of Lourdes Parish, Brisbane The Joyful Mysteries 3B: India (GMT 01.00) local (6.30) Carmelite Community, Northern India The Luminous Mysteries 4: New Zealand (GMT 01.30) local (13.30) The Shrine of Mary, at Pukekaraka Otaki The Sorrowful Mysteries 4A: New Zealand (GMT 01.30) local (13.30) Carmelite Monastery, Aukland The Glorious Mysteries 4B: Thailand (01.45) local (8.45) St. Raphael Kalinowski Carmelite Priory Chapel of the Infant Jesus in Sampran. Glorious Mysteries 5: Singapore (GMT 02.00) local (10.00) Good Shepherd Convent Chapel The Joyful Mysteries 6: Brunei (GMT 02.30) local (10.30) Church of Our Lady’s Assumption The Luminous Mysteries 6A: Vietnam (GMT 02.45) local (09.45) Our Lady of La Vang The Sorrowful Mysteries 7: Philippines (GMT 03.00) local (11.00). The National Shrine of Our Lady of Mount Carmel Parish, New Manila, Quezon City The Glorious Mysteries 8: Philippines (GMT 03.30) local (11.30) Shrine of the -

European Race Audit

EUROPEAN RACE AUDIT BRIEFING PAPER NO.5 - SEPTEMBER 2011 Breivik, the conspiracy theory and the Oslo massacre Contents (1) The conspiracy theory and the Oslo massacre 1 (2) Appendix 1: Responses to the Oslo massacre 14 (3) Appendix 2: Documentation of anti-Muslim violence and other related provocations, Autumn 2010-Summer 2011 18 In a closed court hearing on 25 July 2011, 32-year-old But, as this Briefing Paper demonstrates, the myths that Anders Behring Breivik admitted killing seventy-seven Muslims, supported by liberals, cultural relativists and people on 22 July in two successive attacks in and Marxists, are out to Islamicise Europe and that there is a around the Norwegian capital – the first on government conspiracy to impose multiculturalism on the continent buildings in central Oslo, the second on the tiny island of and destroy western civilisation, are peddled each day Utøya, thirty-eight kilometres from Oslo. But he denied on the internet, in extreme-right, counter-jihadist and criminal responsibility, on the basis that the shooting neo-Nazi circles. In this Briefing Paper we also examine spree on the Norwegian Labour Party summer youth certain intellectual currents within neoconservativism camp, which claimed sixty-nine lives, was necessary to and cultural conservatism. For while we readily admit wipe out the next generation of Labour Party leaders in that these intellectual currents do not support the order to stop the further disintegration of Nordic culture notion of a deliberate conspiracy to Islamicise Europe, from the mass immigration of Muslims, and kick start a they are often used by conspiracy theorists to underline revolution to halt the spread of Islam. -

Lake Resorts & Spas

THE BEST OF AUSTRIA 1 rom soaring alpine peaks in the west to the seem- ingly endless valleys and lowlands in the east, Aus- Ftria’s natural beauty is breathtaking. For over a millennium the region has been at the center of European history and culture. Its lively historic cities, like the capital Vienna, Graz, Innsbruck, and Salzburg are as aesthetically pleasing as their dramatic settings. In summer, Austria’s lakes, rivers, and hiking paths come to life, while the winter months are interwoven with hot-spiced wine and ski excursions. The Austrians are elegant and cultured people with a dark, yet resilient sense of humor and a knack for fashioning lifestyle to fit their needs. From 5th generation country farmers to middle class city dwellers to members of the faded aristocracy, sophistication, beauty, and good food are of the utmost importance. For such a small country, Austria has made more than its fair share of global impact. Besides exports like Linzer Torte, Manner wafers, and Red Bull, Vienna is the third UN headquarters’ city, along with New York and Geneva. With some 17,000 diplomats in residence and conveniently located at the crossroads of eastern and western Europe, Austria has the highest density of foreign intelligence agents in the world. Once the seat of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, today’s Austrian capital Vienna is a bustling metropolis with a strong commitment to the good life, and the city is consistently ranked number 1 in quality of life worldwide. Throughout this book, you’ll find Austria’s choice sights, restaurants, and hotels, and this chapter gives you a glimpse of the very best. -

364.Gyorsárverés Numizmatika

Gyorsárverés 364. numizmatika Az árverés anyaga megtekinthető weboldalunkon és irodánkban (VI. Andrássy út 16. III. emelet. Nyitva tartás: H-Sz: 10-17, Cs: 10-19 óráig, P: Zárva) 2020. 17-20-ig. AJÁNLATTÉTELI HATÁRIDŐ: 2020. február 20. 19 óra. Ajánlatokat elfogadunk írásban, személyesen, vagy postai úton, telefonon a 317-4757, 266-4154 számokon, faxon a 318-4035 számon, e-mailben az [email protected], illetve honlapunkon (darabanth.com), ahol online ajánlatot tehet. ÍRÁSBELI (fax, email) ÉS TELEFONOS AJÁNLATOKAT 18:30-IG VÁRUNK. A megvásárolt tételek átvehetők 2020. február 24-én 10 órától. Utólagos eladás február 27-ig. (Nyitvatartási időn kívül honlapunkon vásárolhat a megmaradt tételekből.) Anyagbeadási határidő a 365. gyorsárverésre: február 20. Az árverés FILATÉLIA, NUMIZMATIKA, KÉPESLAP és az EGYÉB GYŰJTÉSI TERÜLETEK tételei külön katalógusokban szerepelnek! A vásárlói jutalék 22% Részletes árverési szabályzat weboldalunkon és irodánkban megtekinthető darabanth.com Tisztelt Ügyfelünk! 33., tavaszi nagyaukciónkra már várjuk a beadásokat, március végéig! 364. aukció: Megtekintés: február 17-20-ig! Tételek átvétele: február 24. 10 órától 363. aukció elszámolás: február 25-től! Amennyiben átutalással kéri az elszámolását, kérjük jelezze e-mailben, vagy telefonon. Kérjük az elszámoláshoz a tétel átvételi listát szíveskedjenek elhozni! Kezelési költség 240 Ft / tétel / árverés. A 2. indításnál 120 Ft A vásárlói jutalék 22% Tartalomjegyzék: Numizmatikai kellékek 30000-30015 Numizmatikai irodalom 30016-30027 Numizmatikával kapcsolatos