Royal Sanctity and the Writing of History on the Peripheries of Latin Christendom, C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Blote Kan Ein Gjere Om Det Berre Skjer I Løynd Kristenrettane I Gulatingslova Og Gragas Og Forholdet Mellom Dei Gunhild Kværness

Blote kan ein gjere om det berre skjer i løynd Kristenrettane i Gulatingslova og Gragas og forholdet mellom dei Gunhild Kværness Noregs forskingsråd KULTs skriftserie nr. 65 m * 'HI Nasjonalbiblioteket Ef Nasjonalbiblioteket Blote kan ein gjere om det berre skjer i løynd Kristenrettane i Gulatingslova og Gragas og forholdet mellom dei Gunhild Kværness Noregs forskingsråd KUL Ts skriftserie nr. 65 Leiar for forskingsprosjektet Religionsskiftet i Norden: Magnus Rindal Senter for studiar i vikingtid og nordisk mellomalder Universitetet i Oslo Postboks 1016 Blindern 0315 Oslo Telefon: 22 85 29 27 Telefaks: 22 85 29 29 E-post: [email protected] Prosjektet er ein del av Noregs forskingsråds program for Kultur- og tradisjonsformidlande forsking (KULT) onalbiblioteket iblioteket / KULTs skriftserie nr. 65 © Noregs forskingsråd og forfattaren 1996 ISSN 0804-3760 ISBN 82-12-00831-2 Noregs forskingsråd Stensberggata 26 Postboks 2700 St. Hanshaugen 0131 Oslo Telefon: 22 03 70 00 Telefaks: 22 03 70 01 Telefaks bibliotek: 800 83001 (grønn linje) Trykk: GCS Opplag: 450 Oslo, november 1996 ZH0SZ &*L / 0 A 1 78 1 gx fl Nasjonalbiblioteket Depotbiblioteket ". hvatki es missagt es f fræsum bessum, {3a es skylt at hafa bat heidr, es sannara reynisk" (. alle stader der noko er rangt i denne framstillinga, bør ein heller halde seg til det som viser seg å vere sannare) Ari fr6si Porgilsson i Islendingabok Gunhild Kværness fullførte eksamen i hovudfag ved Institutt for nordistikk og litteraturvitskap, Universitetet i Oslo, våren 1995. Ho la då fram avhandlinga Blote kan ein gjere om det berre skjer i løynd. Kristenrettane i Gulatingslova og Grågås og forholdet mellom dei, som var skriven i tilknyting til prosjektet "Religionsskiftet i Norden". -

Adam of Bremen on Slavic Religion

Chapter 3 Adam of Bremen on Slavic Religion 1 Introduction: Adam of Bremen and His Work “A. minimus sanctae Bremensis ecclesiae canonicus”1 – in this humble manner, Adam of Bremen introduced himself on the pages of Gesta Hammaburgensis ecclesiae pontificum, yet his name did not sink into oblivion. We know it thanks to a chronicler, Helmold of Bosau,2 who had a very high opinion of the Master of Bremen’s work, and after nearly a century decided to follow it as a model. Scholarship has awarded Adam of Bremen not only with a significant place among 11th-c. writers, but also in the whole period of the Latin Middle Ages.3 The historiographic genre of his work, a history of a bishopric, was devel- oped on a larger scale only after the end of the famous conflict on investiture between the papacy and the empire. The very appearance of this trend in histo- riography was a result of an increase in institutional subjectivity of the particu- lar Church.4 In the case of the environment of the cathedral in Bremen, one can even say that this phenomenon could be observed at least half a century 1 Adam, [Praefatio]. This manner of humble servant refers to St. Paul’s writing e.g. Eph 3:8; 1 Cor 15:9, and to some extent it seems to be an allusion to Christ’s verdict that his disciples quarrelled about which one of them would be the greatest (see Lk 9:48). 2 Helmold I, 14: “Testis est magister Adam, qui gesta Hammemburgensis ecclesiae pontificum disertissimo sermone conscripsit …” (“The witness is master Adam, who with great skill and fluency described the deeds of the bishops of the Church in Hamburg …”). -

1 Zsuzsanna Ajtony [email protected]

Zsuzsanna Ajtony [email protected] Imagology – National Images and Stereotypes in Literature and Culture (Manfred Beller, Joep Leerssen (eds.) Imagology. The Cultural Construction and Literary Representation of National Characters. Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2007) Stereotyping is a natural ordering function of the human and social mind. Stereotypes make reality easier to deal with because they simplify the complexities that make people unique, and this simplification reflects important beliefs and values as well. People have a rich variety of beliefs about typical members of groups including beliefs about traits, behaviours and values of a typical group member. Social identity theory (Tajfel 1978) considers that our relation to the different social or ethnic categories is inherently asymmetrical. Categorizing people according to their ethnic or national affiliation affects the judgment of their features. The ethnic group we belong to is experienced to be “ingroup biased”, continuously being overestimated as opposed to the outgroup. This asymmetrical relation leads to the emergence of national or ethnic stereotypes. As a result, it is an old and widespread tendency that different societies, races or “nations” are endowed with certain features or even characters. It seems that different people’s relationship to other cultures is characterised by ethnocentrism, i.e. anything that is different from one’s own patterns, is considered to be “other”, strange, anomalous or unique. In several languages, the critical analysis of national stereotypes that appear in literature and in other forms of cultural representation is called imagology or image studies. This technical neologism indicates a relatively novel domain of science that studies the national stereotypes as presented in literature and culture. -

The Origin, Development, and History of the Norwegian Seventh-Day Adventist Church from the 1840S to 1889" (2010)

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertations Graduate Research 2010 The Origin, Development, and History of the Norwegian Seventh- day Adventist Church from the 1840s to 1889 Bjorgvin Martin Hjelvik Snorrason Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations Part of the Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, Christianity Commons, and the History of Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Snorrason, Bjorgvin Martin Hjelvik, "The Origin, Development, and History of the Norwegian Seventh-day Adventist Church from the 1840s to 1889" (2010). Dissertations. 144. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations/144 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your interest in the Andrews University Digital Library of Dissertations and Theses. Please honor the copyright of this document by not duplicating or distributing additional copies in any form without the author’s express written permission. Thanks for your cooperation. ABSTRACT THE ORIGIN, DEVELOPMENT, AND HISTORY OF THE NORWEGIAN SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTIST CHURCH FROM THE 1840s TO 1887 by Bjorgvin Martin Hjelvik Snorrason Adviser: Jerry Moon ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH Dissertation Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Title: THE ORIGIN, DEVELOPMENT, AND HISTORY OF THE NORWEGIAN SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTIST CHURCH FROM THE 1840s TO 1887 Name of researcher: Bjorgvin Martin Hjelvik Snorrason Name and degree of faculty adviser: Jerry Moon, Ph.D. Date completed: July 2010 This dissertation reconstructs chronologically the history of the Seventh-day Adventist Church in Norway from the Haugian Pietist revival in the early 1800s to the establishment of the first Seventh-day Adventist Conference in Norway in 1887. -

Beowulf and Typological Symbolism

~1F AND TYPOLOGICAL SYMBOLISM BEO~LF AND TYPOLOGICAL SY~rnOLISM By WILLEM HELDER A Thesis· Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Ar.ts McMaster University November 1971. MASTER OF ARTS (1971) McMASTER UNIVERSITY (English) - Hamilton~ Ontario ~ and Typological Symbolism AUTHOR, Willem Helder~ BoAe (McMaster University) SUPERVISORt" Dro AQ Ao Lee NUMBER OF PAGESg v~ 100 ii PREFACE In view of the prevalence of Christianity in England throughout what we can consider the age of the f3e.o~ poet, an exploration of the influence o·f typological symbolism would seem to be especially useful in the study of ~f. In the Old English period any Christian influence on a poem would perforce be of a patristic and typological nature. I propose to give evidence that this statement applies also to 13Eio'!llJ..J,=:(, and to bring this information to bear particularly on the inter pretation of the two dominant symbols r Reorot and the dragon's hoardo To date, no attempt has been made to look at the poem as a whole in a purely typological perspectivec. According to the typological exegesis of Scripture, the realities of the Old Testament prefigure those of the new dis~ pensation. The Hebrew prophets and also the New Testament apostles consciously made reference to "types" or II figures II , but it was left for the Fathers of the Church to develop typology as a science. They did so to prove to such h.eretics as the lYIani~ chean8 that both Testaments form a unity, and to convince the J"ews that the Old was fulfilled in the New. -

Introduction the Waste-Ern Literary Canon in the Waste-Ern Tradition

Notes Introduction The Waste-ern Literary Canon in the Waste-ern Tradition 1 . Zygmunt Bauman, Wasted Lives: Modernity and Its Outcasts (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2004), 26. 2 . M a r y D o u g las, Purity and Danger: An Analysis of the Concepts of Pollution and Taboo (London: Routledge, 1966/2002), 2, 44. 3 . S usan Signe Morrison, E xcrement in the Late Middle Ages: Sacred Filth and Chaucer’s Fecopoeticss (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008), 153–158. The book enacts what Dana Phillips labels “excremental ecocriticism.” “Excremental Ecocriticism and the Global Sanitation Crisis,” in M aterial Ecocriticism , ed. Serenella Iovino and Serpil Oppermann (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2014), 184. 4 . M o r r i s o n , Excrementt , 123. 5 . Dana Phillips and Heather I. Sullivan, “Material Ecocriticism: Dirt, Waste, Bodies, Food, and Other Matter,” Interdisci plinary Studies in Literature and Environment 19.3 (Summer 2012): 447. “Our trash is not ‘away’ in landfills but generating lively streams of chemicals and volatile winds of methane as we speak.” Jane Bennett, Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010), vii. 6 . B e n n e t t , Vibrant Matterr , viii. 7 . I b i d . , vii. 8 . S e e F i gures 1 and 2 in Vincent B. Leitch, Literary Criticism in the 21st Century: Theory Renaissancee (London: Bloomsbury, 2014). 9 . Pippa Marland and John Parham, “Remaindering: The Material Ecology of Junk and Composting,” Green Letters: Studies in Ecocriticism 18.1 (2014): 1. 1 0 . S c o t t S lovic, “Editor’s Note,” Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment 20.3 (2013): 456. -

FULLTEXT01.Pdf

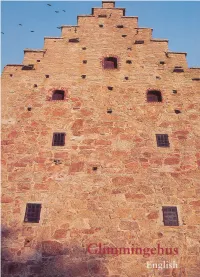

Digitalisering av redan tidigare utgivna vetenskapliga publikationer Dessa fotografier är offentliggjorda vilket innebär att vi använder oss av en undantagsregel i 23 och 49 a §§ lagen (1960:729) om upphovsrätt till litterära och konstnärliga verk (URL). Undantaget innebär att offentliggjorda fotografier får återges digitalt i anslutning till texten i en vetenskaplig framställning som inte framställs i förvärvssyfte. Undantaget gäller fotografier med både kända och okända upphovsmän. Bilderna märks med ©. Det är upp till var och en att beakta eventuella upphovsrätter. SWEDISH NATIONAL HERITAGE BOARD RIKSANTIKVARIEÄMBETET Cultural Monuments in S weden 7 Glimmingehus Anders Ödman National Heritage Board Back cover picture: Reconstruction of the Glimmingehus drawbridge with a narrow “night bridge” and a wide “day bridge”. The re construction is based on the timber details found when the drawbridge was discovered during the excavation of the moat. Drawing: Jan Antreski. Glimmingehus is No. 7 of a series entitled Svenska kulturminnen (“Cultural Monuments in Sweden”), a set of guides to some of the most interesting historic monuments in Sweden. A current list can be ordered from the National Heritage Board (Riksantikvarieämbetet) , Box 5405, SE- 114 84 Stockholm. Tel. 08-5191 8000. Author: Anders Ödman, curator of Lund University Historical Museum Translator: Alan Crozier Photographer: Rolf Salomonsson (colour), unless otherwise stated Drawings: Agneta Hildebrand, National Heritage Board, unless otherwise stated Editing and layout: Agneta Modig © Riksantikvarieämbetet 2000 1:1 ISBN 91-7209-183-5 Printer: Åbergs Tryckeri AB, Tomelilla 2000 View of the plain. Fortresses in Skåne In Skåne, or Scania as it is sometimes called circular ramparts which could hold large in English, there are roughly 150 sites with numbers of warriors, to protect the then a standing fortress or where legends and united Denmark against external enemies written sources say that there once was a and internal division. -

UN GA Gai•! OL®GIAI ALAPKÖNYVTÁR V

UN GA GA i•! OL®GIAI ALAPKÖNYVTÁRV TÁR Könyvjegyzék Kiadja a Nemzetközi Magyar Filológiai Társaság és a Tudományos Ismeretterjesztő Társulat Budapest 1986 Hungarológiai alapkönyvtár -- HUNGAROLÓGIAI ALAPKÖNYVTÁR Könyvjegyzék Kiadja a Nemzetközi Magyar Filológiai Társaság és a Tudományos Ismeretterjesztő Társulat Budapest 1986 A bibliográfiát összeállították: Bevezető rész STAUDER MARIA közreműködésével V. WINDISCH ÉVA Nyelvtudomány D. MATAI MARIA Irodalomtudomány TÓDOR ILDIKÓ és B. HAJTÓ ZSÓFIA Néprajz KOSA LÁSZLÓ Szerkesztette NYERGES JUDIT közreműködésével V. WINDISCH ÉVA Tudományos Ismeretterjesztő Társulat Felelős kiadó: Dr.Rottler Ferenc főtitkár 86.1-199 TIT Nyomda,- -Budapest . - Formátum: A/5 - Terjedelem: 11,125 A/5 ív - Példányszám: 700 Félelős vezető: Dr.Préda Tibor TARTALOMMUTATÓ ELŐSZÓ 9 RŐVIDÍTÉSEK JEGYZÉKE 12 BEVEZETŐ RÉSZ 15 1 A magyarok és Magyarország általában 17 2 A magyar nemzeti bibliográfia 17 2.1 Hungarika-bibliográfiák 19 3 Lexikonok 19 4 Szótárak 20 5 Gyűjtemények katalógusai 21 6 Az egyes tudományterületek segéd- és kézikönyvei 22 6.1 Földrajz, demográfia 22 .6.2 Statisztika 22 6.3 Jog, jogtörténet 22 6.4 Szociológia 23 6.5 Történelem 24 6.51 Általános magyar történeti bibliográfiák, repertóriumok 24 6.511 Történeti folyóiratok repertóriumai 24 6.52 összefoglaló művek, tanulmánykötetek a teljes magyar törté- nelemből 25 6.53 A magyar történelem egyes korszakaira vonatkozó monográ- fiák, tanulmánykötetek, forrásszövegek 28 6.531 Őstörténet, középkor 28 6.532 1526-1849 29 6.533 1849-1919 29 6.534 1919-től napjainkig 30 6.54 Gazdaság- és társadalomtörténet 30 6.55 Művelődéstörténet 32 6.551 Művelődéstörténet általában. Eszmetörténet 32 6.552 Egyháztörténet 33 6.553 Oktatás- és iskolatörténet 33 6.554 Könyvtörténet 35 6.555 Sajtótörténet 35 6.556 Tudománytörténet 36 6.557 Közgyűjtemények, kulturális intézmények története 37 6.558 Életmódtörténet 37 6.56 Történeti segédtudományok. -

Heimskringla III.Pdf

SNORRI STURLUSON HEIMSKRINGLA VOLUME III The printing of this book is made possible by a gift to the University of Cambridge in memory of Dorothea Coke, Skjæret, 1951 Snorri SturluSon HE iMSKrinGlA V oluME iii MAG nÚS ÓlÁFSSon to MAGnÚS ErlinGSSon translated by AliSon FinlAY and AntHonY FAulKES ViKinG SoCiEtY For NORTHErn rESEArCH uniVErSitY CollEGE lonDon 2015 © VIKING SOCIETY 2015 ISBN: 978-0-903521-93-2 The cover illustration is of a scene from the Battle of Stamford Bridge in the Life of St Edward the Confessor in Cambridge University Library MS Ee.3.59 fol. 32v. Haraldr Sigurðarson is the central figure in a red tunic wielding a large battle-axe. Printed by Short Run Press Limited, Exeter CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ................................................................................ vii Sources ............................................................................................. xi This Translation ............................................................................. xiv BIBLIOGRAPHICAL REFERENCES ............................................ xvi HEIMSKRINGLA III ............................................................................ 1 Magnúss saga ins góða ..................................................................... 3 Haralds saga Sigurðarsonar ............................................................ 41 Óláfs saga kyrra ............................................................................ 123 Magnúss saga berfœtts .................................................................. 127 -

Large Castles and Large War Machines In

Large castles and large war machines in Denmark and the Baltic around 1200: an early military revolution? Autor(es): Jensen, Kurt Villads Publicado por: Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra URL persistente: URI:http://hdl.handle.net/10316.2/41536 DOI: DOI:https://doi.org/10.14195/2183-8925_30_11 Accessed : 5-Oct-2021 17:35:20 A navegação consulta e descarregamento dos títulos inseridos nas Bibliotecas Digitais UC Digitalis, UC Pombalina e UC Impactum, pressupõem a aceitação plena e sem reservas dos Termos e Condições de Uso destas Bibliotecas Digitais, disponíveis em https://digitalis.uc.pt/pt-pt/termos. Conforme exposto nos referidos Termos e Condições de Uso, o descarregamento de títulos de acesso restrito requer uma licença válida de autorização devendo o utilizador aceder ao(s) documento(s) a partir de um endereço de IP da instituição detentora da supramencionada licença. Ao utilizador é apenas permitido o descarregamento para uso pessoal, pelo que o emprego do(s) título(s) descarregado(s) para outro fim, designadamente comercial, carece de autorização do respetivo autor ou editor da obra. Na medida em que todas as obras da UC Digitalis se encontram protegidas pelo Código do Direito de Autor e Direitos Conexos e demais legislação aplicável, toda a cópia, parcial ou total, deste documento, nos casos em que é legalmente admitida, deverá conter ou fazer-se acompanhar por este aviso. impactum.uc.pt digitalis.uc.pt Kurt Villads Jensen * Revista de Historia das Ideias Vol. 30 (2009) LARGE CASTLES AND LARGE WAR MACHINES IN DENMARK AND THE BALTIC AROUND 1200 - AN EARLY MILITARY REVOLUTION? In 1989, the first modern replica in Denmark of a medieval trebuchet was built on the open shore near the city of Nykobing Falster during the commemoration of the 700th anniversary of the granting of the city's charter, and archaeologists and interested amateurs began shooting stones out into the water of the sound between the islands of Lolland and Falster. -

Battle of Stiklestad: Supporting Virtual Heritage with 3D Collaborative Virtual Environments and Mobile Devices in Educational Settings

Archived at the Flinders Academic Commons http://dspace.flinders.edu.au/dspace/ Originally published at: Proceedings of Mobile and Ubiquitous Technologies for Learning (UBICOMM 07), Papeete, Tahiti, 04-09 November 2007, pp. 197-203 Copyright © 2007 IEEE. Published version of the paper reproduced here in accordance with the copyright policy of the publisher. Personal use of this material is permitted. However, permission to reprint/republish this material for advertising or promotional purposes or for creating new collective works for resale or redistribution to servers or lists, or to reuse any copyrighted component of this work in other works must be obtained from the IEEE. International Conference on Mobile Ubiquitous Computing, Systems, Services and Technologies Battle of Stiklestad: Supporting Virtual Heritage with 3D Collaborative Virtual Environments and Mobile Devices in Educational Settings Ekaterina Prasolova-Førland Theodor G. Wyeld Monica Divitini, Anders Lindås Norwegian University of Adelaide University Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Adelaide, Australia Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway [email protected] Trondheim, Norway [email protected] [email protected], [email protected] Abstract sociological significance. From reconstructions recording historical information about these sites a 3D Collaborative Virtual Environments (CVEs) realistic image of how these places might have looked in the past can be created. This also allows inhabiting have been widely used for preservation of cultural of these reconstructed spaces with people and artifacts heritage, also in an educational context. This paper for users to interact with. All these features can act as a presents a project where 3D CVE is augmented with valuable addition to a ‘traditional’ educational process mobile devices in order to support a collaborative in history and related subjects. -

Bulletin 2004.Pdf

BULLETIN 2004 Responsible editor: István Monok ❦ Editor: Péter Ekler Translation: Eszter Timár, Elayne Antalffy Publication manager: Barbara Kiss Design: László Kiss ❦ Address and contacts: National Széchényi Library H–1827 Budapest, Buda Royal Palace Wing F, Hungary http://www.oszk.hu phone: (1) 22 43 700 fax: (1) 20 20 804 e-mail: [email protected] ❦ Cover 1: The Apponyi Room of the library Cover 2: Pelbartus de Themeswar: Pomerium de sanctis (Augsburg, 1502) App. H 1583 Cover 3: Janus Pannonius: Panegyricus in laudem Baptistae Guarini Veronensis (Wien, 1512) App. H 1613 Cover 4: The Széchényi Family’s coat of arm Cover photos: József Hapák Pictures illustrating the featured articles are representing the art objects of the exhibition “The World of Yesterday”. Photos taken by Ágnes Bakos and Bence Tihanyi (BTM) ❦ THE NATIONAL SZÉCHÉNYI LIBRARY IS SUPPORTED BY issn: 1589-004x CONTENTS 5 PLAN FOR THE ESTABLISHMENT OF A EUROPEAN CENTRE OF BOOK HISTORY MOKKA-R: THE DIGITAL SHARED CATALOGUE 9 OF EARLY PRINTS FOUND IN THE CARPATHIAN BASIN 1 3 MAGYAR HELIKON. SERIES OF FACSIMILES OF OUR BOOK TREASURES RETROSPECTIVE CONVERSION OF OUR BOOK CATALOGUES IN PROGRESS 1 7 2 1 THE WORLD OF YESTERDAY. LITERARY CONNECTIONS AND ZEITGEIST FROM HISTORICISM TO AVANT-GARDE SÁNDOR APPONYI THE BIBLIOPHILE AND HIS 27 COLLECTION OF HUNGARICA 3 1 MODERNISATION OF OUR MUSIC COLLECTION WITH JAPANESE GOVERNMENT AID OUR ILLUSTRIOUS GUESTS 3 3 3 5 ZOLTÁN FALLENBÜCHL IS EIGHTY )3( Arthur Schnitzler was one of the best known representatives of Austrian literature among the Hungarian readers at the turn of the century. His play, Der Ruf des Lebens was first published in Hungarian by Nyugat Könyvtár, a considerable review being written on it by Zoltán Ambrus in Nyugat 1911.