The Election That Never

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

95 Garrett Liberal Party and General Election of 1915

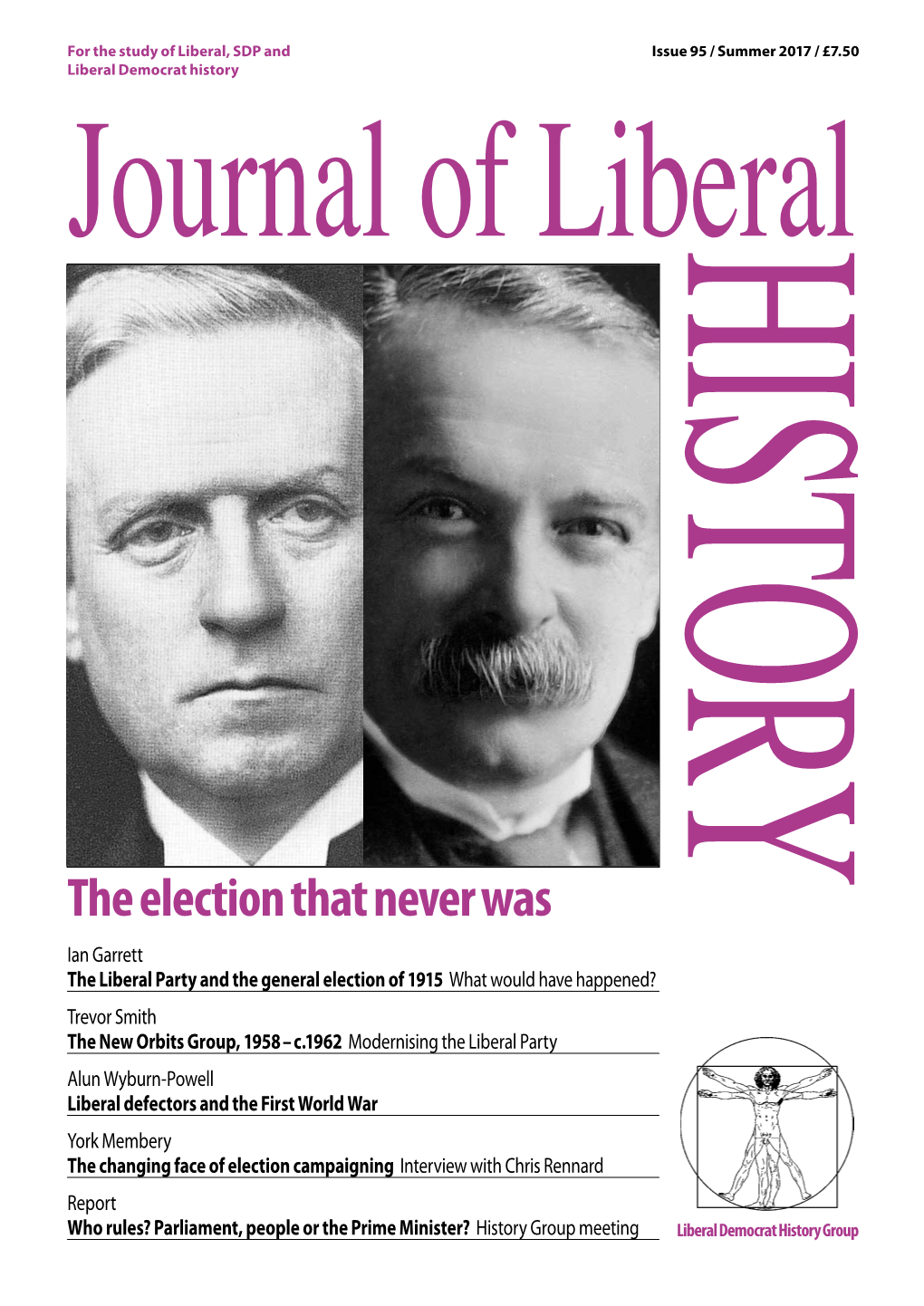

Counterfactual Ian Garrett considers what could have happened in the general election due in 1915 but postponed because of the outbreak of war The Liberal Party and the General Election of 1915 4 Journal of Liberal History 95 Summer 2017 The Liberal Party and the General Election of 1915 lections at the beginning of the twen- outbreak of the First World War provided a suit- tieth century were not of course held on ably dramatic climax to the collapse of Liberal Eone day, as they have been since 1918. Nor, government and party. therefore, would election counts have taken place More modern popular histories have come to largely overnight – it took several weeks for elec- similar conclusions. A. N. Wilson, another writer tion results to emerge from around the country. of fluent prose but shaky history, saw Britain as Nevertheless, it is easy to imagine the sort of stu- in the grip of ‘strikes and industrial unrest … of dio conversations that might have taken place in a proportion unseen since 1848’,3 embroiled in the early stages of a hypothetical election night such an ‘impasse’ over Ireland in 1914 that war broadcast. If war had not broken out, and the seemed preferable as a way out, as something that election of 1915 taken place as expected, would ‘could rally the dissident voices of the Welsh, the such a conversation have proceeded something women, the Irish behind a common cause’.4 And like this? if neither Dangerfield nor Wilson seem particu- larly rigorous, it has proved remarkably difficult ‘Well, Peter Snow, over to you – how is it look- to escape the former’s shadow. -

39 Pack SDP Chronology

CHRONOLOGY OF THE SDP Compiled by Mark Pack 1979 3 May General election won by the Tories. Defeated Labour MPs include Shirley Williams. June Social Democrat Alliance (SDA) reorganises itself into a network of local groups, not all of whose members need be in the Labour Party. July ‘Inquest on a movement’ by David Marquand appears in Encounter. 22 November Roy Jenkins delivers the Dimbleby Lecture, ‘Home thoughts from abroad’. 30 November Bill Rodgers gives a speech at Abertillery: ‘Our party has a year, not much longer, in which to save itself.’ 20 December Meeting of Jenkinsites and others considering forming a new party, organised by Colin Phipps. Robert Maclennan declines invitation. 1980 January NEC refuses to publish report from Reg Underhill detailing Trotskyite infiltration of Labour. 1 May Local elections. Liberal vote changes little, though seats are gained with large advances in Liverpool and control of Adur and Hereford. 31 May Labour Special Conference at Wembley. Policy statement Peace, Jobs, Freedom, including pro-unilateralism and anti-EEC policies, supported. Owen is deeply angered by vitriolic heckling during his speech. 7 June Owen, Rodgers and Williams warn they will leave Labour if it supports withdrawal from the EEC: ‘There are some of us who will not accept a choice between socialism and Europe. We will choose them both.’ 8 June Williams warns that a centre party would have ‘no roots, no principles, no philosophy and no values.’ 9 June Roy Jenkins delivers lecture to House of Commons Press Gallery, calling for a realignment of the ‘radical centre’. 15 June Labour’s Commission of Inquiry backs use of an electoral college for electing the leader and mandatory reselection of MPs. -

97 Winter 2017–18 3 Liberal History News Winter 2017–18

For the study of Liberal, SDP and Issue 97 / Winter 2017–18 / £7.50 Liberal Democrat history Journal of LiberalHI ST O R Y The Forbidden Ground Tony Little Gladstone and the Contagious Diseases Acts J. Graham Jones Lord Geraint of Ponterwyd Biography of Geraint Howells Susanne Stoddart Domesticity and the New Liberalism in the Edwardian press Douglas Oliver Liberals in local government 1967–2017 Meeting report Alistair J. Reid; Tudor Jones Liberalism Reviews of books by Michael Freeden amd Edward Fawcett Liberal Democrat History Group “David Laws has written what deserves to become the definitive account of the 2010–15 coalition government. It is also a cracking good read: fast-paced, insightful and a must for all those interested in British politics.” PADDY ASHDOWN COALITION DIARIES 2012–2015 BY DAVID LAWS Frank, acerbic, sometimes shocking and often funny, Coalition Diaries chronicles the historic Liberal Democrat–Conservative coalition government through the eyes of someone at the heart of the action. It offers extraordinary pen portraits of all the personalities involved, and candid insider insight into one of the most fascinating periods of recent British political history. 560pp hardback, £25 To buy Coalition Diaries from our website at the special price of £20, please enter promo code “JLH2” www.bitebackpublishing.com Journal of Liberal History advert.indd 1 16/11/2017 12:31 Journal of Liberal History Issue 97: Winter 2017–18 The Journal of Liberal History is published quarterly by the Liberal Democrat History Group. ISSN 1479-9642 Liberal history news 4 Editor: Duncan Brack Obituary of Bill Pitt; events at Gladstone’s Library Deputy Editors: Mia Hadfield-Spoor, Tom Kiehl Assistant Editor: Siobhan Vitelli Archive Sources Editor: Dr J. -

'The Left's Views on Israel: from the Establishment of the Jewish State To

‘The Left’s Views on Israel: From the establishment of the Jewish state to the intifada’ Thesis submitted by June Edmunds for PhD examination at the London School of Economics and Political Science 1 UMI Number: U615796 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615796 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 F 7377 POLITI 58^S8i ABSTRACT The British left has confronted a dilemma in forming its attitude towards Israel in the postwar period. The establishment of the Jewish state seemed to force people on the left to choose between competing nationalisms - Israeli, Arab and later, Palestinian. Over time, a number of key developments sharpened the dilemma. My central focus is the evolution of thinking about Israel and the Middle East in the British Labour Party. I examine four critical periods: the creation of Israel in 1948; the Suez war in 1956; the Arab-Israeli war of 1967 and the 1980s, covering mainly the Israeli invasion of Lebanon but also the intifada. In each case, entrenched attitudes were called into question and longer-term shifts were triggered in the aftermath. -

Reports to Conference Spring 2015 Contents

REPORTS TO CONFERENCE SPRING 2015 CONTENTS Contents Page Federal Conference Committee……….……………………….……………..4 Federal Policy Committee......................…………...……………………......9 Federal Executive.............………………... ………………………………...17 Federal Finance and Administration Committee………….….…..............25 Parliamentary Party (Commons)……………………………. ……………...29 …………. Parliamentary Party (Lords)………………………..………………………...35 Parliamentary Party (Europe)………………………….……………………..41 Campaign for Gender Balance……………………………………………...45 Diversity Engagement Group……………………………………………..…50 3 Federal Conference Committee Glasgow 2015 Last autumn we went back to Glasgow for the second year running. As in 2013 we received a superb welcome from the city. We continue to ask all attendees to complete an online feedback questionnaire. A good percentage complete this but I would urge all members to take the time to participate. It is incredibly useful to the conference office and FCC and does influence whether we visit a venue again and if we do, what changes we need to try and make. FCC Changes Following the committee elections at the end of last year there were a number of changes to the membership of FCC. Qassim Afzal, Louise Bloom, Sal Brinton, Prateek Buch, Veronica German, Evan Harris and David Rendel either did not restand or were not re-elected. All played a valuable role on FCC and will be missed. We welcome Jon Ball, Zoe O’Connell and Mary Reid onto the committee as directly elected members. FPC have elected two new representatives onto FCC and we welcome back Linda Jack and Jeremy Hargreaves in these roles. Both have previously served on FCC so are familiar with the way we work. One of the FE reps is also new with Kaavya Kaushik joining James Gurling as an FE rep on FCC. -

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan) -

Special Historic Section 0 What the General Election Numbers Mean - Michael Steed 0 Runners and Riders for Next Leader

0 Liberator at 50 - special historic section 0 What the general election numbers mean - Michael Steed 0 Runners and Riders for next leader Issue 400 - April 2020 £ 4 Issue 400 April 2020 SUBSCRIBE! CONTENTS Liberator magazine is published six/seven times per year. Commentary.............................................................................................3 Subscribe for only £25 (£30 overseas) per year. Radical Bulletin .........................................................................................4..5 You can subscribe or renew online using PayPal at ALL GOOD THINGS COME TO AN END ............................................5 You’ll soon by seeing Liberator only as a free PDF, not in print. Here, the Liberator our website: www.liberator.org.uk Collective explains why, and how this will work Or send a cheque (UK banks only), payable to RUNNERS AND RIDERS .........................................................................6..7 “Liberator Publications”, together with your name Liberator offers a look at Lib Dem leadership contenders and full postal address, to: NEVER WASTE A CRISIS .......................................................................8..9 Be very afraid, even when coronavirus is over, about what the government will seize Liberator Publications the opportunity to do, says Tony Greaves Flat 1, 24 Alexandra Grove GET LIBERALISM DONE .....................................................................10..11 London N4 2LF The answers to the Liberal Democrats’ plight can all be found in the party’s -

The Delius Society Journal Spring 2001, Number 129

The Delius Society Journal Spring 2001, Number 129 The Delius Society (Registered Charity No. 298662) Full Membership and Institutions £20 per year UK students £10 per year US/\ and Canada US$38 per year Africa, Aust1alasia and far East £23 per year President Felix Aprahamian Vice Presidents Lionel Carley 131\, PhD Meredith Davies CBE Sir Andrew Davis CBE Vernon l Iandley MA, FRCM, D Univ (Surrey) Richard I Iickox FRCO (CHM) Lyndon Jenkins Tasmin Little f CSM, ARCM (I Ions), I Jon D. Lilt, DipCSM Si1 Charles Mackerras CBE Rodney Meadows Robc1 t Threlfall Chain11a11 Roge1 J. Buckley Trcaswc1 a11d M11111/Jrrship Src!l'taiy Stewart Winstanley Windmill Ridge, 82 Jlighgate Road, Walsall, WSl 3JA Tel: 01922 633115 Email: delius(alukonlinc.co.uk Serirta1y Squadron Lcade1 Anthony Lindsey l The Pound, Aldwick Village, West Sussex P021 3SR 'fol: 01243 824964 Editor Jane Armour-Chclu 17 Forest Close, Shawbirch, 'IC!ford, Shropshire TFS OLA Tel: 01952 408726 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.dclius.org.uk Emnil: [email protected]. uk ISSN-0306-0373 Ch<lit man's Message............................................................................... 5 Edilot ial....................... .... .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. ... 6 ARTICLES BJigg Fair, by Robert Matthew Walker................................................ 7 Frede1ick Delius and Alf1cd Sisley, by Ray Inkslcr........... .................. 30 Limpsficld Revisited, by Stewart Winstanley....................................... 35 A Forgotten Ballet ?, by Jane Armour-Chclu -

Management Plan 2012 ‐ 2023

ST CATHERINE’S HILL & TOWN COMMON MANAGEMENT PLAN 2012 ‐ 2023 FINAL DRAFT SEPTEMBER 2012 We value our local countryside for its natural beauty and wildlife. This area has been influenced by past generations and is now cared for by a partnership that will take its needs into account for all to enjoy into the future. St Catherine’s Hill & Town Common Management Plan – Final Draft St Catherine’s Hill & Town Common Management Plan 2012 ‐ 2023 Prepared by the St Catherine’s Hill & Town Common Management Plan Steering Group, including Christchurch Borough Council Countryside Service in association with Jude Smith, Rick Minter and Alison Parfitt. “On behalf of the Steering Group I believe that this Plan brings forward a balanced approach to securing the future management of the habitats and landscape on St Catherine’s Hill and Town Common. This will ensure that the most important features are conserved and enhanced with the active involvement of local people. I therefore commend this Plan to you.” Councillor Sue Spittle Chairman, St Catherine’s Hill & Town Common Management Plan Steering Group Citation For bibliography purposes this management plan should be referred to as: Smith, J.E., Parfitt A., Minter, R. & Christchurch Countryside Service. 2012. St Catherine's Hill & Town Common Management Plan, 2012 ‐ 2023. Prepared for St Catherine’s Hill & Town Common Management Plan Steering Group, c/o Christchurch Borough Council, Christchurch. Alison Parfitt Tel: 01242 584982 E‐mail: [email protected] St Catherine’s Hill & Town Common Management Plan – Final Draft CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................ 1 Background....................................................................................................................... 1 Work of the Steering Group ............................................................................................. -

Fixed-Term Parliaments Act

House of Commons House of Lords Joint Committee on the Fixed-Term Parliaments Act Report Session 2019–21 Report, together with formal minutes relating to the report Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 18 March 2021 Ordered by the House of Lords to be printed 18 March 2021 HC 1046 HL 253 Published on 24 March 2021 by authority of the House of Commons and House of Lords Joint Committee on the Fixed-Term Parliaments Act The Joint Committee was appointed to: (a) carry out a review of the operation of the Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011, pursuant to section 7 of that Act, and if appropriate in consequence of its findings, make recommendations for the repeal or amendment of that Act; and (b) consider, as part of its work under subparagraph (a), and report on any draft Government Bill on the repeal of the Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011 presented to both Houses in this session. Membership House of Lords House of Commons Lord McLoughlin (Chair) (Conservative) Aaron Bell MP (Conservative, Newcastle- under-Lyme) Lord Beith (Liberal Democrat) Chris Bryant MP (Labour, Rhondda) Lord Grocott (Labour) Jackie Doyle-Price MP (Conservative, Lord Jay of Ewelme (Crossbench) Thurrock) Baroness Lawrence of Clarendon (Labour) Dame Angela Eagle MP (Labour, Wallasey) Lord Mancroft (Conservative) Maria Eagle MP (Labour, Garston and Halewood) Peter Gibson MP (Conservative, Darlington) Mr Robert Goodwill MP (Conservative, Scarborough and Whitby) David Linden MP (Scottish National Party, Glasgow East) Alan Mak MP (Conservative, Havant) Mrs Maria Miller MP -

Benjamin Britten's Liturgical Music and Its Place in the Anglican

Benjamin Britten’s liturgical music and its place in the Anglican Church Music Tradition By Timothy Miller Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Music and Sound Recording School of Arts, Communication and Humanities University of Surrey August 2012 ©Timothy Miller 2012 ProQuest Number: 10074906 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10074906 Published by ProQuest LLO (2019). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLO. ProQuest LLO. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.Q. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract This study presents a detailed analysis of the liturgical music of Benjamin Britten (1913- 1976). In addition to several pieces Britten wrote for the Anglican liturgy and one for the Roman Catholic Church, a number of other works, not originally composed for liturgical purpose, but which fonction well in a liturgical setting, are included, providing a substantial repertory which has hitherto received little critical commentary. Although not occupying a place of central importance in the composer’s musical output, it is argued that a detailed examination of this liturgical music is important to form a fuller understanding of Britten’s creative character; it casts additional light on the composer’s technical procedures (in particular his imaginative exploitation of tonal structure which embraced modality, free-tonality and twelve-tone ideas) and explores further Britten’s commitment to the idea of a composer serving society. -

62 Cole Yellow Glass Ceiling

ThE YEllow GLAss CEiliNG THE MYSTERY of THE disAppEARING LIBERAL woMEN MPS After women became he 1950 Liberal mani- in promoting women into Par- festo boasted proudly liament and government, the eligible to stand for that ‘the part played Liberal Party managed to do election to Parliament by women in the so again only two years before in 1918, the first councils of the Liberal its own disappearance in the TParty is shown by our unani- merger of 1988. The reasons woman Liberal MP mous adoption of a programme for this striking famine are in for women drawn up by women some ways a familiar story from was elected in 1921. Yet Liberals.’1 Certainly, the two the experience of other parties; only six women ever main parties at that time gave a but there is a dimension to the lower profile to women’s status causes which is distinctively Lib- sat as Liberal MPs, and as an issue, and Liberal policy eral, and which persists today. half of them won only demanding equal pay entitled the party to regard its propos- one election, half were als as, in one reviewer’s assess- Women Liberal MPs elected at by-elections, ment, ‘more Radical than the Only six women ever sat as Lib- Labour Party’s.’2 These pro- eral MPs, and they had an unu- and all but one were posals were, as the manifesto sual profile: half of them won directly related acknowledged, in part the only one election, half were result of the efforts of an almost elected at by-elections, and all to Liberal leaders.