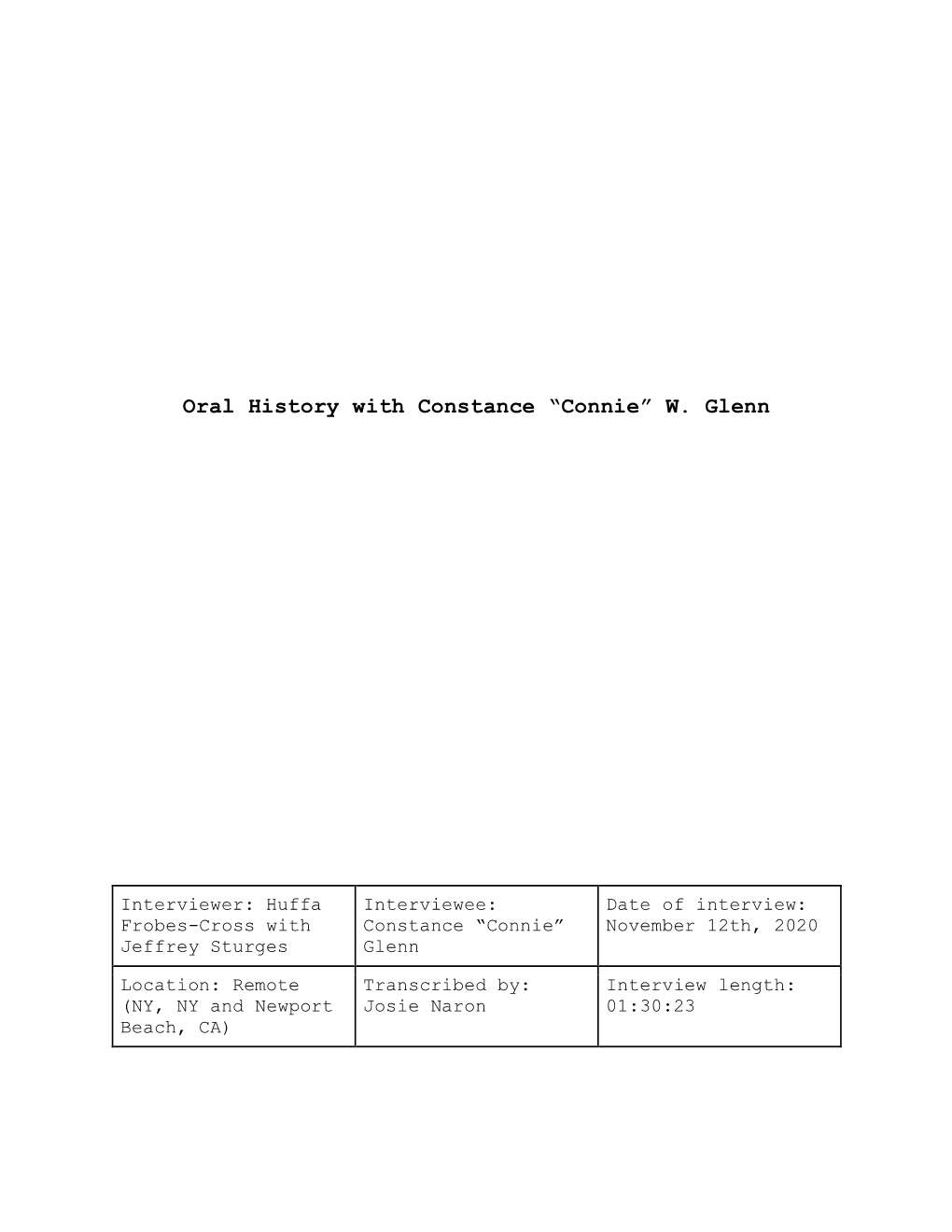

“Connie” W. Glenn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 12. the Avant-Garde in the Late 20Th Century 1

Chapter 12. The Avant-Garde in the Late 20th Century 1 The Avant-Garde in the Late 20th Century: Modernism becomes Postmodernism A college student walks across campus in 1960. She has just left her room in the sorority house and is on her way to the art building. She is dressed for class, in carefully coordinated clothes that were all purchased from the same company: a crisp white shirt embroidered with her initials, a cardigan sweater in Kelly green wool, and a pleated skirt, also Kelly green, that reaches right to her knees. On her feet, she wears brown loafers and white socks. She carries a neatly packed bag, filled with freshly washed clothes: pants and a big work shirt for her painting class this morning; and shorts, a T-shirt and tennis shoes for her gym class later in the day. She’s walking rather rapidly, because she’s dying for a cigarette and knows that proper sorority girls don’t ever smoke unless they have a roof over their heads. She can’t wait to get into her painting class and light up. Following all the rules of the sorority is sometimes a drag, but it’s a lot better than living in the dormitory, where girls have ten o’clock curfews on weekdays and have to be in by midnight on weekends. (Of course, the guys don’t have curfews, but that’s just the way it is.) Anyway, it’s well known that most of the girls in her sorority marry well, and she can’t imagine anything she’d rather do after college. -

Andy Warhol Who Later Became the Most

Jill Crotty FSEM Warhol: The Businessman and the Artist At the start of the 1960s Roy Lichtenstein, Claes Oldenburg and Robert Rauschenberg were the kings of the emerging Pop Art era. These artists transformed ordinary items of American culture into famous pieces of art. Despite their significant contributions to this time period, it was Andy Warhol who later became the most recognizable icon of the Pop Art Era. By the mid sixties Lichtenstein, Oldenburg and Rauschenberg each had their own niche in the Pop Art market, unlike Warhol who was still struggling to make sales. At one point it was up to Ivan Karp, his dealer, to “keep moving things moving forward until the artist found representation whether with Castelli or another gallery.” 1Meanwhile Lichtenstein became known for his painted comics, Oldenburg made sculptures of mass produced food and Rauschenberg did combines (mixtures of everyday three dimensional objects) and gestural paintings. 2 These pieces were marketable because of consumer desire, public recognition and aesthetic value. In later years Warhol’s most well known works such as Turquoise Marilyn (1964) contained all of these aspects. Some marketable factors were his silk screening technique, his choice of known subjects, his willingness to adapt his work, his self promotion, and his connection to art dealers. However, which factor of Warhol’s was the most marketable is heavily debated. I believe Warhol’s use of silk screening, well known subjects, and self 1 Polsky, R. (2011). The Art Prophets. (p. 15). New York: Other Press New York. 2 Schwendener, Martha. (2012) "Reinventing Venus And a Lying Puppet." New York Times, April 15. -

Arc of Achievement Unites Brant and Mellon

SATURDAY, OCTOBER 10, 2020 THIS SIDE UP: ARC OF JACKIE=S WARRIOR LOOMS LARGE IN CHAMPAGNE ACHIEVEMENT UNITES Undefeated Jackie=s Warrior (Maclean=s Music) looks to continue his domination of the 2-year-old colt division as the BRANT AND MELLON headliner in Belmont=s GI Champagne S. Saturday, a AWin and You=re In@ for the Breeders= Cup. A debut winner at Churchill June 19, the bay scored a decisive win in the GII Saratoga Special S. Aug. 7 and was an impressive victor of the GI Runhappy Hopeful S. at Saratoga Sept. 7, earning a 95 Beyer Speed Figure. "He handles everything well," said trainer Steve Asmussen's Belmont Park-based assistant trainer Toby Sheets. "Just like his races are, that's how he is. He's done everything very professionally and he's very straightforward. I don't see the mile being an issue at all." Asmussen also saddles Midnight Bourbon (Tiznow) in this event. Earning his diploma by 5 1/2 lengths at second asking at Ellis Aug. 22, the bay was second in the GIII Iroquois S. at Churchill Sept. 5. Cont. p7 Sottsass won the Arc for Brant Sunday | Scoop Dyga IN TDN EUROPE TODAY by Chris McGrath PRETTY GORGEOUS RISES IN FILLIES’ MILE When Ettore Sottsass was asked which of his many diverse In the battle of the TDN Rising Stars, it was Pretty Gorgeous (Fr) achievements had given him most satisfaction, he gave a shrug. that bested Indigo Girl (GB) in Friday’s G1 Fillies’ Mile at "I don't know," he said. -

Tom Wesselmann Selected Catalogues Bibliography 2019 'Tom Wesselmann', Susan Davidson, Almine Rech Editions

Tom Wesselmann Selected Catalogues Bibliography 2019 'Tom Wesselmann', Susan Davidson, Almine Rech Editions 2016 'Tom Wesselmann - A Different Kind of Woman', Almine Rech, Brenda Schmahmann and Anne Pasternak, Almine Rech Editions 2015 Alexander, Darsie, ‘International Pop Art’, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis Germano Celant (Ed.), ‘Arts & Foods, Expo Milano and Mondadori Electa’, Verona, Italy 2014 ‘Art or Sound’, (exhibition catalogue) Fondazione Prada, Venice, Italy ‘Pop to Popism’, (exhibition catalogue), Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia ‘Ludwig Goes Pop’, (exhibition catalogue), Museum Ludwig, Cologne, Germany ‘The Shaped Canvas’, Revisited, (exhibition catalogue) Luxembourg & Dayan, New York 2013 John Wilmerding, ‘The Pop Object: The Still Life Tradition in Pop Art’ (exhibition catalogue), New York, Acquavella Galleries & Rizzoli ‘Tom Wesselmann, Works on Paper – Steel Drawings – Screenprints – Paintings’, (exhibition catalogue), Samuel Vanhoegaerden Gallery, Knokke, Belgium ‘Ileana Sonnabend; Ambassador for the New’, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, (exhibition catalogue) 2012 Stéphane Aquin, ‘Beyond Pop Art, Tom Wesselmann’ (exhibition catalogue), Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, Montreal, Quebec and Delmonico Books, New York Mildred Glimcher, ‘Happenings’, New York, 1958-1963, Monacelli Press, New York 2011 ‘Tom Wesselmann Draws’ (exhibition catalogue), The Kreeger Museum, Washington, DC 2010 ‘Tom Wesselmann, Plastic Works’, Maxwell Davidson Gallery, New York, (exhibition catalogue) Judith Goldman, Robert & Ethel -

Marianne Boesky Gallery Frank Stella

MARIANNE BOESKY GALLERY NEW YORK | ASPEN FRANK STELLA BIOGRAPHY 1936 Born in Malden, MA Lives and works in New York, NY EDUCATION 1950 – 1954 Phillips Academy (studied painting under Patrick Morgan), Andover, MA 1954 – 1958 Princeton University (studied History and Art History under Stephen Greene and William Seitz), Princeton, NJ SELECTED SOLO AND TWO-PERSON EXHIBITIONS 2021 Brussels, Belgium, Charles Riva Collection, Frank Stella & Josh Sperling, curated by Matt Black September 8 – November 20, 2021 [two-person exhibition] 2020 Ridgefield, CT, Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, Frank Stella’s Stars, A Survey, September 21, 2020 – September 6, 2021 Tampa, FL, Tampa Museum of Art, Frank Stella: What You See, April 2 – September 27, 2020 Tampa, FL, Tampa Museum of Art, Frank Stella: Illustrations After El Lissitzky’s Had Gadya, April 2 – September 27, 2020 Stockholm, Sweeden, Wetterling Gallery, Frank Stella, March 19 – August 22, 2020 2019 Los Angeles, CA, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Frank Stella: Selection from the Permanent Collection, May 5 – September 15, 2019 New York, NY, Marianne Boesky Gallery, Frank Stella: Recent Work, April 25 – June 22, 2019 Eindhoven, The Netherlands, Van Abbemuseum, Tracking Frank Stella: Registering viewing profiles with eye-tracking, February 9 – April 7, 2019 2018 Tuttlingen, Germany, Galerie der Stadt Tuttlingen, FRANK STELLA – Abstract Narration, October 6 – November 25, 2018 Los Angeles, CA, Sprüth Magers, Frank Stella: Recent Work, September 14 – October 26, 2018 Princeton, NJ, Princeton University -

Thomas Demand Roxana Marcoci, with a Short Story by Jeffrey Eugenides

Thomas Demand Roxana Marcoci, with a short story by Jeffrey Eugenides Author Marcoci, Roxana Date 2005 Publisher The Museum of Modern Art ISBN 0870700804 Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/116 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history— from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art museumof modern art lIOJ^ArxxV^ 9 « Thomas Demand Thomas Demand Roxana Marcoci with a short story by Jeffrey Eugenides The Museum of Modern Art, New York Published in conjunction with the exhibition Thomas Demand, organized by Roxana Marcoci, Assistant Curator in the Department of Photography at The Museum of Modern Art, New York, March 4-May 30, 2005 The exhibition is supported by Ninah and Michael Lynne, and The International Council, The Contemporary Arts Council, and The Junior Associates of The Museum of Modern Art. This publication is made possible by Anna Marie and Robert F. Shapiro. Produced by the Department of Publications, The Museum of Modern Art, New York Edited by Joanne Greenspun Designed by Pascale Willi, xheight Production by Marc Sapir Printed and bound by Dr. Cantz'sche Druckerei, Ostfildern, Germany This book is typeset in Univers. The paper is 200 gsm Lumisilk. © 2005 The Museum of Modern Art, New York "Photographic Memory," © 2005 Jeffrey Eugenides Photographs by Thomas Demand, © 2005 Thomas Demand Copyright credits for certain illustrations are cited in the Photograph Credits, page 143. Library of Congress Control Number: 2004115561 ISBN: 0-87070-080-4 Published by The Museum of Modern Art, 11 West 53 Street, New York, New York 10019-5497 (www.moma.org) Distributed in the United States and Canada by D.A.P./Distributed Art Publishers, New York Distributed outside the United States and Canada by Thames & Hudson Ltd., London Front and back covers: Window (Fenster). -

JASPER JOHNS 1930 Born in Augusta, Georgia Currently Lives

JASPER JOHNS 1930 Born in Augusta, Georgia Currently lives and works in Connecticut and Saint Martin Education 1947-48 Attends University of South Carolina 1949 Parsons School of Design, New York Selected Solo Exhibitions 2009 Focus: Jasper Johns, The Museum of Modern Art, New York 2008 Jasper Johns: Black and White Prints, Bobbie Greenfield Gallery, Santa Monica, California Jasper Johns: The Prints, The Madison Museum of Contemporary Art, Madison, Wisconsin Jasper Johns: Drawings 1997 – 2007, Matthew Marks Gallery, New York Jasper Johns: Gray, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 2007 Jasper Johns: From Plate to Print, Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven Jasper Johns: Gray, Art Institute of Chicago; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York Jasper Johns-An Allegory of Painting, 1955-1965, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC; Kunstmuseum Basel, Switzerland States and Variations: Prints by Jasper Johns, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. 2006 Jasper Johns: From Plate to Print, Yale University Art Gallery Jasper Johns: Usuyuki, Craig F. Starr Associates, New York 2005 Jasper Johns: Catenary, Matthew Marks Gallery, New York Jasper Johns: Prints, Amarillo Museum of Art, Amarillo, Texas 2004 Jasper Johns: Prints From The Low Road Studio, Leo Castelli Gallery, New York 2003 Jasper Johns: Drawings, The Menil Collection, Houston, Texas Jasper Johns: Numbers, Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland; Los Angeles County Museum of Art Past Things and Present: Jasper Johns since 1983, Walker Art Center Minneapolis; Greenville County Museum of -

American Friends Musée D'orsay San Francisco Trip Itinerary February 3

American Friends Musée d’Orsay San Francisco Trip Itinerary February 3-5, 2016 AFMO welcomes you to celebrate opening of the Pierre Bonnard: Painting Arcadia exhibition at the Legion of Honor And to Enjoy Exceptional Private Homes, Collections and Art Tours Itinerary (more detailed information on activities can be found below this itinerary) Wednesday, February 3 John and Gretchen Berggruen Home and Private Collection (5pm) Welcome Dinner at The Park Tavern in the private dining room, The Eden Lounge (7pm) Thursday, February 4 Frances Bowes Home and Private Collection (late morning) Lunch hosted by Sotheby's at The Wayfare Tavern Tea at the home of Diane Wilsey, President of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco (FAMSF), to view her collection (4pm) Donors' Opening of Pierre Bonnard: Painting Arcadia exhibition at Legion of Honor, AFMO group invited by the FAMSF (6:30-8:30pm) Friday, February 5 Curator-led tour of Pier 24 Photography, the private photographs museum (10-11:30am) Pricing of trip, per person: $1750: for AFMO members at the Sponsor level and above ($1000+ level, these levels are “Dual”, thus valid for two people, this $1750/person member trip price is valid for up to two participants/membership). $2000: for non-members or members at the Friend level ($250-$999, this level is valid for one person only.) Hotel information: We are holding a limited number of rooms at the Hotel Vitale, a luxury boutique hotel near the Embarcadero and Financial District that was recommended to AFMO. Please contact the AFMO office about reserving a room: by email at [email protected] or by telephone at (212) 508-1639. -

The Unexpected and Influential Berggruen Gallery

The Unexpected and Influential Berggruen Gallery May 2019 Barely a stone’s throw from the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, I recently discovered Berggruen Gallery, a three-story art gallery with bright and airy windows. The unusual setting immediate piqued my interest, as most galleries prefer to wall over the windows to create studio lighting. Walking past the location on my daily trek to work, I am able to catch glimpses of sculptures and paintings inside the sparely decorated building. Finally my curiosity gets the best of me and I decide to use my lunch hour to explore the unique space. My first impression of the gallery with its natural-colored woods and simple white walls is that it feels welcoming and friendly. Although I walk in without an appointment, the receptionist enthusiastically greets me and encourages me to explore the space. As I wander around, my eye is immediately drawn to a split staircase on my right. When I look downstairs, I can sense a large cavernous space beneath me, and glancing up at the soaring ceilings, I can make out a few pieces on the upper landing. It creates the sense that the entire building is open and transparent. While I’m there, I have an opportunity to speak with Gretchen Berggruen, who owns the gallery along with partner and husband John Berggruen. Originally located on Grant Avenue for four 10 HAWTHORNE STREET SAN FRANCISCO CA 94105 TEL 415 781 4629 [email protected] BERGGRUEN.COM decades, the gallerists relocated to Hawthorne Street in early 2017 with help from architect Jennifer Weiss (who also happens to be Gretchen’s daughter). -

Hold Still: Looking at Photorealism RICHARD KALINA

Hold Still: Looking at Photorealism RICHARD KALINA 11 From Lens to Eye to Hand: Photorealism 1969 to Today presents nearly fifty years of paintings and watercolors by key Photorealist taken care of by projecting and tracing a photograph on the canvas, and the actual painting consists of varying degrees (depending artists, and provides an opportunity to reexamine the movement’s methodology and underlying structure. Although Photorealism on the artist) of standard under- and overpainting, using the photograph as a color reference. The abundance of detail and incident, can certainly be seen in connection to the history, style, and semiotics of modern representational painting (and to a lesser extent while reinforcing the impression of demanding skill, actually makes things easier for the artist. Lots of small things yield interesting late-twentieth-century art photography), it is worth noting that those ties are scarcely referred to in the work itself. Photorealism is textures—details reinforce neighboring details and cancel out technical problems. It is the larger, less inflected areas (like skies) that contained, compressed, and seamless, intent on the creation of an ostensibly logical, self-evident reality, a visual text that relates are more trouble, and where the most skilled practitioners shine. almost entirely to its own premises: the stressed interplay between the depiction of a slice of unremarkable three-dimensional reality While the majority of Photorealist paintings look extremely dense and seem similarly constructed from the ground up, that similarity is and the meticulous hand-painted reproduction of a two-dimensional photograph. Each Photorealist painting is a single, unambiguous, most evident either at a normal viewing distance, where the image snaps together, or in the reducing glass of photographic reproduction. -

Interview Transcripts Peter Brant

Washington Post Peter Brant, childhood friend Peter Brant: I do consider him a friend in the sense that we knew each other so well. But by the time that he left around 13 to go to New York Military Academy, I think that I really didn’t have much contact with him until he came back to New York and was in business for -- you know, he’s a success coming into the New York. I didn’t really see him very much, hardly at all until the ‘80s and then I kind of reconnected with him in the ‘90s and we were social friends. I played golf with him. He’d been to my house several times in the ‘90s. Michael E. Miller (Washington Post): This one here or -- Brant: No. Miller: Connecticut? Brant: No, I’d been to Mar-a-Lago, not a member there but my sister is. I was a member of the golf course that he has here in Palm Beach but only because it was a corporate membership. And my partner at that time, who is my cousin, who’d been my partner for many, many years and whose father was my father’s partner, loves to play golf and he was a member. So I might have played there twice in my life, you know. So there’s no real connection then. You know, he would write me a letter every now and then, just talking about marriage or whatever and -- 1 Miller: Seeking your advice on things or -- Brant: No, no, no, no, no. -

Frankie on Snowfall in Cazoo Oaks

THURSDAY, 3 JUNE 2021 FRANKIE ON SNOWFALL LAST CALL FOR BREEZERS AT GORESBRIDGE IN NEWMARKET By Emma Berry IN CAZOO OAKS NEWMARKET, UKCCA little later than scheduled, the European 2-year-old sales season will conclude on Thursday with the Tattersalls Ireland Goresbridge Breeze-up, which has returned to Newmarket for a second year owing to ongoing Covid travel restrictions. What was already a bumper catalogue for a one-day sale of more than 200 horses has been beefed up still by the inclusion of 16 wild cards that have been rerouted from other recent sales for a variety of reasons. They include horses with some pretty starry pedigrees, so be prepared for some of the major action to take place late in the day. Indeed the last three catalogued all have plenty to recommend them on paper. Lot 241 from Mayfield Stables is the American Pharoah colt out of the Irish champion 2-year-old filly Damson (Ire) (Entrepreneur). Cont. p5 Snowfall | PA Sport IN TDN AMERICA TODAY by Tom Frary BAFFERT SUSPENDED FROM CHURCHILL AFTER MEDINA Aidan O=Brien has booked Frankie Dettori for the G3 Musidora SPLIT POSITIVE S. winner Snowfall (Jpn) (Deep Impact {Jpn}) in Friday=s G1 Trainer Bob Baffert was suspended for two years by Churchill Downs Cazoo Oaks at Epsom, for which 14 fillies were confirmed on after the split sample of GI Kentucky Derby winner Medina Spirit (Protonico) came back positive. Click or tap here to go straight to Wednesday. Registering a career-best when winning by 3 3/4 TDN America.