Interview Transcripts Peter Brant

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Leah Johnson

Roman - iii LEAH JOHNSON Scholastic Press / New York i_328_9781338503265.indd 3 1/8/20 2:38 PM Roman - iv Text copyright © 2020 by Leah Johnson Photos © Shutterstock: i crown and throughout (Anne Punch), i background and throughout (InnaPoka), 1 background and throughout (alexdndz), 31 icons and throughout (marysuper studio), 55, 180 emojis (Rawpixel . com). All rights reserved. Published by Scholastic Press, an imprint of Scholastic Inc., Publishers since 1920. scholastic, scholastic press, and associated log os are trademarks and/or registered trademarks of Scholastic Inc. The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third- party websites or their content. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or other wise, without written permission of the publisher. For information regarding permission, write to Scholastic Inc., Attention: Permissions Department, 557 Broadway, New York, NY 10012. This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data available ISBN 978-1-338-50326-5 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 20 21 22 23 24 Printed in the U.S.A. 23 First edition, June 2020 Book design by Stephanie Yang i_328_9781338503265.indd 4 1/8/20 2:38 PM one I’m clutching my tray with both hands, hoping that Beyoncé grants me the strength to make it to my usual lunch table without any incidents. -

Don Jr. Thinks Trump Is Acting Crazy”: the President’S COVID Joyride Has the Family Divided | Vanity Fair

10/7/2020 “Don Jr. Thinks Trump Is Acting Crazy”: The President’s COVID Joyride Has the Family Divided | Vanity Fair 2020 “Don Jr. Thinks Trump Is Acting Crazy”: The President’s COVID Joyride Has the Family Divided The president’s recklessness at Walter Reed has Don Jr. pushing for an intervention, but Ivanka and Jared “keep telling Trump how great he’s doing,” a source says. B Y G A B R I E L S H E R M A N OCTOBER 5, 2020 BY GRAEME SLOAN/BLOOMBERG/GETT Y IMAGES. https://www.vanityfair.com/news/2020/10/don-jr-thinks-trump-is-acting-crazy-presidents-covid-joyride-has-family-divided 1/4 10/7/2020 “Don Jr. Thinks Trump Is Acting Crazy”: The President’s COVID Joyride Has the Family Divided | Vanity Fair onald Trump’s erratic and reckless behavior in the last 24 hours has opened a rift in the Trump family over how to rein in the out-of-control president, according to two Republicans briefed on the family conversations. Sources said Donald Trump Jr. is deeply upset by his father’s decision to drive around Walter Reed National Military DMedical Center last night with members of the Secret Service while he was infected with COVID-19. “Don Jr. thinks Trump is acting crazy,” one of the sources told me. The stunt outraged medical experts, including an attending physician at Walter Reed. According to sources, Don Jr. has told friends that he tried lobbying Ivanka Trump, Eric Trump, and Jared Kushner to convince the president that he needs to stop acting unstable. -

Prototyp Moderného Obrancu Slovenský Hokejista Michal Čajkovský Sa V Sparte Praha Stal Jedným Z Najlepších Obrancov Najvyššej Českej Súťaže

25 rokov tipovania na Slovensku nike.sk NAJLEPŠIE KURZY – SUPERŠANCA 1 X 2 5408 MAR. ČILIČ – R. BAUTISTA AGUT 1,38 3,00 8:05 5415 C. SUAREZOVÁ NAVARROVÁ – E. KULIČKOVOVÁ 1,32 3,30 11:05 12651 BANSKÁ BYSTRICA – HK POPRAD 1,63 4,60 4,25 17:30 12652 KOMETA BRNO – HC PARDUBICE 1,63 4,55 4,65 18:00 12653 INGOLSTADT – SCHWENNINGEN 1,53 4,95 4,90 19:30 12631 NANCY – NIMES 1,48 3,80 7,60 20:00 Piatok • 22. 1. 2016 • 70. ročník • číslo 17 • cena 0,60 12632 HAMBURG – BAYERN MNÍCHOV 11,8 6,35 1,24 20:30 12621 F. LOPEZ – J. ISNER 2,30 1,60 0:05 App Store pre iPad a iPhone / Google Play pre Android 12622 M. RAONIC – V. TROICKI 1,27 3,70 0:05 Adam Žampa sa na štart Bohatší TV program v Kitzbüheli postaví pre športovcov za každú cenu Strana 37 POZOR! UŽ DNES Chlpy nie sú problémStrana 44 odkazuje majster sveta Peter Sagan médiám, ktoré si zobrali na mušku jeho nohy Strany 10 a 11 WWW.SPORT.SK Prototyp moderného obrancu Slovenský hokejista Michal Čajkovský sa v Sparte Praha stal jedným z najlepších obrancov najvyššej českej súťaže. 2 NÁZORY piatok ❘ 22. 1. 2016 PRIAMA REČ Lákadlom je RICHARDA LINTNERA atraktívny trojkový formát Optimizmus pre zápasom hokejo- žérov odohrajú proti sebe dva zápasy vých hviezd vo mne vyvoláva fakt, že Na Slovensku celkom isto (hrací čas 20 minút), víťazi sa stretnú po dlhých rokoch je naša súťaž sku- „bude aj Winter Classic, nevieme však kedy. -

Vaccine Rollout Underway Governor Prioritizes Vaccinations for Those Ages 65 and Older; Local Front-Line Caregivers, fi Rst Responders Receive Doses

7A COVID-19 case count Get the latest on testing, new cases, and number of deaths in Pinellas County. 2021 the danger zone for box offi cece What movies will lure audiences back into the theaters? Check out our list of 12 of the most anticipated fi lms of 2021. 3B December 31, 2020 www.TBNweekly.com Volume 42, No. 41 * Visit TBNweekly.com/coronavirus for more TRACKING THE CORONAVIRUS CRISIS Also Inside COVID-19 Vaccine rollout underway Governor prioritizes vaccinations for those ages 65 and older; local front-line caregivers, fi rst responders receive doses and Drug Administration’s emergency use across the state have received doses of number should start going up in the near authorization Dec. 18 and is the second By SUZETTE PORTER the COVID-19 vaccines, and as a part of vaccine to receive this approval. future. their allocation, hospitals received enough Tampa Bay Newspapers Gov. Ron DeSantis released an execu- Adam Rudd, CEO of Largo Medical Cen- rst doses to vaccinate their entire frontline tive order Dec. 23 that says the state’s fi ter said, “The safety of our caregivers has As of Christmas day, 113,946 Florid- health care staff and have vaccine remain- phase of the vaccine shall only be used remained fi rst and foremost throughout ians had received their fi rst dose of the ing. St. Pete Beach on long-term care facilities residents and this pandemic and we are excited that we COVID-19 vaccine, including 8,832 in Pi- Largo Medical Center recently an- staff; persons age 65 and older; and health are now able to provide COVID-19 vac- The Game of Kings will return to the nellas County, according to a report from nounced it had started vaccination clinics cines to our frontline caregivers. -

Rule Changes Promise Exciting Season

Online Guide to the main events of the English POLO season FINANCIAL TIMES SPECIAL REPORT | Saturday May 26 2012 ft.com/polo www.ft.com/polo | twitter.com/ftreports Rule changes promise exciting season Patrons have rethought teams, raising expectations of a year of surprises, writes Bob Sherwood he English high-goal polo sea- son is shaping up to be one of the most open and unpredicta- ble for years, with all of the 16 Tor so teams that will compete at the top level having undergone significant reshuffles of professional players this year. Add to that the return of one of polo’s great forces, Ellerston – whose patron is James Packer, son of Kerry Packer, the late Australian media tycoon and polo enthusiast – to UK high goal for the first time since 2008, and expectations of a classic season have rarely been higher. Unusually, polo insiders have been loath to make predictions. Even the professionals chose to sit on the fence when contributing to the annual Polo Times predictions for the season. “So many teams and combinations have changed that it is difficult to know how it’s going to turn out,” says Max Routledge, the 21-year-old five- goal professional and one of the Eng- lish game’s rising stars. Alterations to handicaps forced Alterations designed to speed up the game and stop the best players from hogging the ball have contributed to some surprising results Reuters some of the changes. However, Routledge believes changes to polo’s best option. The combined handicap of includes Luke Tomlinson, the Eng- Cartier, the jewellery maker, switched rule book in 2011, designed to speed a high-goal team must not exceed 22. -

Publications Student Award Winner

©Sidelines, Inc.,Volume 2014$4.00 2601 All Rights- January Reserved 2014 For Horse People • About Horse People www.sidelinesnews.com January 2014 Stunning: Special Stallion and Breeding Section Quentin Judge and HH Dark de la Hart In this issue: • How Leah Little Beat Cancer • Foxhunting With Rita Mae Brown • Ricky Bostwick’s Polo Life FOR HORSE PEOPLE • ABOUT HORSE PEOPLE SIDELINES JANUARY 2014 1 Incorporating 20 HORSES USA PUBLISHER Samantha Charles [email protected] EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Jan Westmark [email protected] 828-575-3965 Contents ASsistant Editor Dani Moritz Senior Staff Writer Lauren Giannini What’s Happenin’ Eventing CONTRIBUTING WRITERS 34 Ingate Alexa Cheater, Arianna Delin, 76 Woodge Fulton: Sydney Masters-Durieux, 98 Off Centerline Doris Degner-Foster, Amy Herzog, When Opportunity Knocks Kathryn Murphy, Kim MacMillan, 116 Asides Katie Navarra, Jennifer Ward, 86 USC Aiken Eventing Team Marissa Quigley PHOTOGRAPHERS 102 Eric Moore: David Lominska, Jack Mancini , Features Flashpoint, Alan Fabricant, Susan Stickle Lauren R. Giannini, Shawn McMillen 16 Second Chances From Football to the Show Ring Kim & Allen MacMillan, Emily Allongo, 20 Anything Is Possible: Leah Little Anne Hoover, Beth Grant, Mandy Su SIDELINES COLUMNISTS 44 Good Food Hunting: Polo Sophie St. Clair – Juniorside Lisa Hollister, Esq - Equine Law A Taste of New Year’s 70 Ricky Bostwick’s Polo Life Ann Reilly - Sports Psychology 50 My Story: Back to the Future with Butet Maria Wynne – European Connection INTERNS 60 Foxhunting with Rita Mae Brown -

NOTHING to HIDE: Tools for Talking (And Listening) About Data Privacy for Integrated Data Systems

NOTHING TO HIDE: Tools for Talking (and Listening) About Data Privacy for Integrated Data Systems OCTOBER 2018 Acknowledgements: We extend our thanks to the AISP Network and Learning Community, whose members provided their support and input throughout the development of this toolkit. Special thanks to Whitney Leboeuf, Sue Gallagher, and Tiffany Davenport for sharing their experiences and insights about IDS privacy and engagement, and to FPF Policy Analyst Amy Oliver and FPF Policy Intern Robert Martin for their contributions to this report. We would also like to thank our partners at Third Sector Capital Partners and the Annie E. Casey Foundation for their support. This material is based upon work supported by the Corporation for National and Community Service (CNCS). Opinions or points of view expressed in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official position of, or a position that is endorsed by, CNCS or the Social Innovation Fund. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 2 Why engage and communicate about privacy? ................................................................................................................................................. 2 Using this toolkit to establish social license to integrate data ..................................................................................................................... -

Whose History and by Whom: an Analysis of the History of Taiwan In

WHOSE HISTORY AND BY WHOM: AN ANALYSIS OF THE HISTORY OF TAIWAN IN CHILDREN’S LITERATURE PUBLISHED IN THE POSTWAR ERA by LIN-MIAO LU (Under the Direction of Joel Taxel) ABSTRACT Guided by the tenet of sociology of school knowledge, this study examines 38 Taiwanese children’s trade books that share an overarching theme of the history of Taiwan published after World War II to uncover whether the seemingly innocent texts for children convey particular messages, perspectives, and ideologies selected, preserved, and perpetuated by particular groups of people at specific historical time periods. By adopting the concept of selective tradition and theories of ideology and hegemony along with the analytic strategies of constant comparative analysis and iconography, the written texts and visual images of the children’s literature are relationally analyzed to determine what aspects of the history and whose ideologies and perspectives were selected (or neglected) and distributed in the literary format. Central to this analysis is the investigation and analysis of the interrelations between literary content and the issue of power. Closely related to the discussion of ideological peculiarities, historians’ research on the development of Taiwanese historiography also is considered in order to examine and analyze whether the literary products fall into two paradigms: the Chinese-centric paradigm (Chinese-centricism) and the Taiwanese-centric paradigm (Taiwanese-centricism). Analysis suggests a power-and-knowledge nexus that reflects contemporary ruling groups’ control in the domain of children’s narratives in which subordinate groups’ perspectives are minimalized, whereas powerful groups’ assumptions and beliefs prevail and are perpetuated as legitimized knowledge in society. -

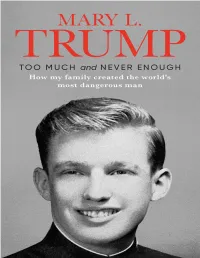

Donald Had Started Branding All of His Buildings in Manhattan, My Feelings About My Name Became More Complicated

Thank you for downloading this Simon & Schuster ebook. Join our mailing list to get updates on new releases, deals, recommended reads, and more from Simon & Schuster. CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP Already a subscriber? Provide your email again so we can register this ebook and send you more of what you like to read. You will continue to receive exclusive offers in your inbox. For my daughter, Avary, and my dad If the soul is left in darkness, sins will be committed. The guilty one is not he who commits the sin, but the one who causes the darkness. —Victor Hugo, Les Misérables Author’s Note Much of this book comes from my own memory. For events during which I was not present, I relied on conversations and interviews, many of which are recorded, with members of my family, family friends, neighbors, and associates. I’ve reconstructed some dialogue according to what I personally remember and what others have told me. Where dialogue appears, my intention was to re-create the essence of conversations rather than provide verbatim quotes. I have also relied on legal documents, bank statements, tax returns, private journals, family documents, correspondence, emails, texts, photographs, and other records. For general background, I relied on the New York Times, in particular the investigative article by David Barstow, Susanne Craig, and Russ Buettner that was published on October 2, 2018; the Washington Post; Vanity Fair; Politico; the TWA Museum website; and Norman Vincent Peale’s The Power of Positive Thinking. For background on Steeplechase Park, I thank the Coney Island History Project website, Brooklyn Paper, and a May 14, 2018, article on 6sqft.com by Dana Schulz. -

What Would Happen If Melania and Donald Trump Got a Divorce?

2/7/2020 What Happens If Melania and Donald Trump Get A Divorce - Melania Trump's Prenup Details SUBSCRIBE SIGN IN What Would Happen If Melania and Donald Trump Got a Divorce? We asked high-profile divorce attorneys to speculate on the prenup—and what a presidential breakup would look like. by CORYNNE CIRILLI JAN 12, 2018 PHILIP FRIEDMAN/STUDIO D (TORN PHOTOGRAPH); CHIP SOMODEVILLA/GETTY IMAGES (TRUMPS) avesdrop on a steakhouse lunch between divorce attorneys and you’re likely to hear them engaging in their current favorite sport: speculating on the marital arrangement between Donald E and Melania Trump. “We love talking about it,” one recently told me. “What’s in the prenup? Did it get renegotiated during the campaign, or after he won? How would a split play out?... It’s irresistible conversational fodder.” During his two previous divorces, Trump stuck mostly to the prenup; although Ivana Trump contested it, she reportedly got $14 million, a New York apartment, a Connecticut mansion, and Mar-a-Lago once a year, as well as $650,000 annually for alimony and child support. Marla Maples contested hers, too, and is said to have been awarded around $2 million. But now that the stakes are higher, we asked a few of the country’s top matrimonial lawyers for their take on what could happen if the rst couple were to split. T&C;: HOW IS THE TRUMP PRENUPTIAL AGREEMENT MOST LIKELY STRUCTURED? Thomas Kretchmar, associate, Chemtob Moss & Forman: I can’t speak to them directly, but in a New York high-net-worth marriage, a prenup is primarily designed to https://www.townandcountrymag.com/society/politics/a14481104/melania-donald-trump-divorce/ 1/6 2/7/2020 What Happens If Melania and Donald Trump Get A Divorce - Melania Trump's Prenup Details protect what is already owned prior to the marriage, versus things that may be accumulated moving forward. -

Arc of Achievement Unites Brant and Mellon

SATURDAY, OCTOBER 10, 2020 THIS SIDE UP: ARC OF JACKIE=S WARRIOR LOOMS LARGE IN CHAMPAGNE ACHIEVEMENT UNITES Undefeated Jackie=s Warrior (Maclean=s Music) looks to continue his domination of the 2-year-old colt division as the BRANT AND MELLON headliner in Belmont=s GI Champagne S. Saturday, a AWin and You=re In@ for the Breeders= Cup. A debut winner at Churchill June 19, the bay scored a decisive win in the GII Saratoga Special S. Aug. 7 and was an impressive victor of the GI Runhappy Hopeful S. at Saratoga Sept. 7, earning a 95 Beyer Speed Figure. "He handles everything well," said trainer Steve Asmussen's Belmont Park-based assistant trainer Toby Sheets. "Just like his races are, that's how he is. He's done everything very professionally and he's very straightforward. I don't see the mile being an issue at all." Asmussen also saddles Midnight Bourbon (Tiznow) in this event. Earning his diploma by 5 1/2 lengths at second asking at Ellis Aug. 22, the bay was second in the GIII Iroquois S. at Churchill Sept. 5. Cont. p7 Sottsass won the Arc for Brant Sunday | Scoop Dyga IN TDN EUROPE TODAY by Chris McGrath PRETTY GORGEOUS RISES IN FILLIES’ MILE When Ettore Sottsass was asked which of his many diverse In the battle of the TDN Rising Stars, it was Pretty Gorgeous (Fr) achievements had given him most satisfaction, he gave a shrug. that bested Indigo Girl (GB) in Friday’s G1 Fillies’ Mile at "I don't know," he said. -

Idioms-And-Expressions.Pdf

Idioms and Expressions by David Holmes A method for learning and remembering idioms and expressions I wrote this model as a teaching device during the time I was working in Bangkok, Thai- land, as a legal editor and language consultant, with one of the Big Four Legal and Tax companies, KPMG (during my afternoon job) after teaching at the university. When I had no legal documents to edit and no individual advising to do (which was quite frequently) I would sit at my desk, (like some old character out of a Charles Dickens’ novel) and prepare language materials to be used for helping professionals who had learned English as a second language—for even up to fifteen years in school—but who were still unable to follow a movie in English, understand the World News on TV, or converse in a colloquial style, because they’d never had a chance to hear and learn com- mon, everyday expressions such as, “It’s a done deal!” or “Drop whatever you’re doing.” Because misunderstandings of such idioms and expressions frequently caused miscom- munication between our management teams and foreign clients, I was asked to try to as- sist. I am happy to be able to share the materials that follow, such as they are, in the hope that they may be of some use and benefit to others. The simple teaching device I used was three-fold: 1. Make a note of an idiom/expression 2. Define and explain it in understandable words (including synonyms.) 3. Give at least three sample sentences to illustrate how the expression is used in context.