Race, Colour and West Indian Cricket in CLR James

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sample Download

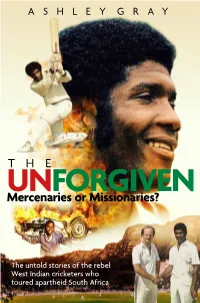

ASHLEY GRAY THE UN FORGIVEN THE MercenariesUNFORGIVEN or Missionaries? The untold stories of the rebel West Indian cricketers who toured apartheid South Africa Contents Introduction. 9. Lawrence Rowe . 26. Herbert Chang . 56. Alvin Kallicharran . 71 Faoud Bacchus . 88 Richard Austin . .102 . Alvin Greenidge . 125 Emmerson Trotman . 132 David Murray . .137 . Collis King . 157. Sylvester Clarke . .172 . Derick Parry . 189 Hartley Alleyne . .205 . Bernard Julien . .220 . Albert Padmore . .238 . Monte Lynch . 253. Ray Wynter . 268. Everton Mattis . .285 . Colin Croft . 301. Ezra Moseley . 309. Franklyn Stephenson . 318. Acknowledgements . 336 Scorecards. .337 . Map: Rebel Origins. 349. Selected Bibliography . 350. Lawrence Rowe ‘He was a hero here’ IT’S EASY to feel anonymous in the Fort Lauderdale sprawl. Shopping malls, car yards and hotels dominate the eyeline for miles. The vast concrete expanses have the effect of dissipating the city’s intensity, of stripping out emotion. The Gallery One Hilton Fort Lauderdale is a four-star monolith minutes from the Atlantic Ocean. Lawrence Rowe, a five-star batsman in his prime, is seated in the hotel lounge area. He has been trading off the anonymity of southern Florida for the past 35 years, an exile from Kingston, Jamaica, the highly charged city that could no longer tolerate its stylish, contrary hero. Florida is a haven for Jamaican expats; it’s a short 105-minute flight across the Caribbean Sea. Some of them work at the hotel. Bartender Alyssa, a 20-something from downtown Kingston, is too young to know that the neatly groomed septuagenarian she’s serving a glass of Coke was once her country’s most storied sportsman. -

Cricket Memorabilia Society Postal Auction Closing at Noon 10

CRICKET MEMORABILIA SOCIETY POSTAL AUCTION CLOSING AT NOON 10th JULY 2020 Conditions of Postal Sale The CMS reserves the right to refuse items which are damaged or unsuitable, or we have doubts about authenticity. Reserves can be placed on lots but must be agreed with the CMS. They should reflect realistic values/expectations and not be the “highest price” expected. The CMS will take 7% of the price realised, the vendor 93% which will normally be paid no later than 6 weeks after the auction. The CMS will undertake to advertise the memorabilia for auction on its website no later than 3 weeks prior to the closing date of the auction. Bids will only be accepted from CMS members. Postal bids must be in writing or e-mail by the closing date and time shown above. Generally, no item will be sold below 10% of the lower estimate without reference to the vendor.. Thus, an item with a £10-15 estimate can be sold for £9, but not £8, without approval. The incremental scale for the acceptance of bids is as follows: £2 increments up to £20, then £20/22/25/28/30 up to £50, then £5 increments to £100 and £10 increments above that. So, if there are two postal bids at £25 and £30, the item will go to the higher bidder at £28. Should there be two identical bids, the first received will win. Bids submitted between increments will be accepted, thus a £52 bid will not be rounded either up or down. Items will be sent to successful postal bidders the week after the auction and will be sent by the cheapest rate commensurate with the value and size of the item. -

Black Internationalism and African and Caribbean

BLACK INTERNATIONALISM AND AFRICAN AND CARIBBEAN INTELLECTUALS IN LONDON, 1919-1950 By MARC MATERA A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in History Written under the direction of Professor Bonnie G. Smith And approved by _______________________ _______________________ _______________________ _______________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey May 2008 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Black Internationalism and African and Caribbean Intellectuals in London, 1919-1950 By MARC MATERA Dissertation Director: Bonnie G. Smith During the three decades between the end of World War I and 1950, African and West Indian scholars, professionals, university students, artists, and political activists in London forged new conceptions of community, reshaped public debates about the nature and goals of British colonialism, and prepared the way for a revolutionary and self-consciously modern African culture. Black intellectuals formed organizations that became homes away from home and centers of cultural mixture and intellectual debate, and launched publications that served as new means of voicing social commentary and political dissent. These black associations developed within an atmosphere characterized by a variety of internationalisms, including pan-ethnic movements, feminism, communism, and the socialist internationalism ascendant within the British Left after World War I. The intellectual and political context of London and the types of sociability that these groups fostered gave rise to a range of black internationalist activity and new regional imaginaries in the form of a West Indian Federation and a United West Africa that shaped the goals of anticolonialism before 1950. -

The Empire Strikes Back

nother Test match series it spelt out an enlightened prophecy of between England and the what was to come. West Indians gets under way - and again, no doubt, But patronising paternalism had a long Amore than a few Englishmen will be course to run yet. Oh dear me, it did. complaining before the summer is out Three years after that first tour by that the West Indians do not have a Hawke's men, Pelham Warner's older proper appreciation of the grand old brother, RSA Aucher Warner, brought game. In as much as they hit too hard the first 'unofficial' (as Lord's called it) with the bat, and bowl too fast with the collective and multiracial team across ball. to England. It was made up of players Although the regular challenge between from Trinidad, Barbados, and British the two sides has only been deemed Guiana. On the day they disembarked at 'official' by the mandarins of the Eng¬ Southampton from the banana boat, the lish game at Lord's for just over 60 London Evening Star carried a large years, we are in fact fast approaching a cartoon featuring Dr WG Grace, the The centenary of cricket contests between English cricket champion, in a tower¬ the Caribbean teams and the 'Mother ing, regal pose, bat in hand instead of Country' of the old British Empire. scimitar, while around him cowered The first English touring side was led and simpered seven or eight black men, Empire by the redoubtable autocrat, Lord 'I all shedding tears and imploring the shave twice a day, my professionals doctor, 'sorry, sah, we have only come only once: a sign we each know our to learn, sah'. -

House of Lords Official Report

Vol. 807 Tuesday No. 138 3 November 2020 PARLIAMENTARYDEBATES (HANSARD) HOUSE OF LORDS OFFICIAL REPORT ORDEROFBUSINESS Questions Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy....................619 Qualifications .................................................................................................................622 Life in the UK Test ........................................................................................................626 Covid-19: Christmas Breaches of Restrictions ...............................................................629 Covid-19: Places of Worship Private Notice Question ..................................................................................................632 Business of the House Motion on Standing Orders .............................................................................................636 Conduct Committee Motion to Agree..............................................................................................................637 Prisoners (Disclosure of Information About Victims) Bill Commons Reason............................................................................................................644 Non-Domestic Rating (Rates Retention, Levy and Safety Net and Levy Account: Basis of Distribution) (Amendment) Regulations 2020 Motion to Approve ..........................................................................................................649 Defence and Security Public Contracts (Amendment) (EU Exit) Regulations 2020 Motion -

Cricket As a Diasporic Resource for Caribbean-Canadians by Janelle Beatrice Joseph a Thesis Submitted in Conformity with the Re

Cricket as a Diasporic Resource for Caribbean-Canadians by Janelle Beatrice Joseph A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Exercise Sciences University of Toronto © Janelle Beatrice Joseph 2010 Cricket as a Diasporic Resource for Caribbean-Canadians Janelle Beatrice Joseph Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Exercise Sciences University of Toronto 2010 Abstract The diasporic resources and transnational flows of the Black diaspora have increasingly been of concern to scholars. However, the making of the Black diaspora in Canada has often been overlooked, and the use of sport to connect migrants to the homeland has been virtually ignored. This study uses African, Black and Caribbean diaspora lenses to examine the ways that first generation Caribbean-Canadians use cricket to maintain their association with people, places, spaces, and memories of home. In this multi-sited ethnography I examine a group I call the Mavericks Cricket and Social Club (MCSC), an assembly of first generation migrants from the Anglo-Caribbean. My objective to “follow the people” took me to parties, fundraising dances, banquets, and cricket games throughout the Greater Toronto Area on weekends from early May to late September in 2008 and 2009. I also traveled with approximately 30 MCSC members to observe and participate in tours and tournaments in Barbados, England, and St. Lucia and conducted 29 in- depth, semi-structured interviews with male players and male and female supporters. I found that the Caribbean diaspora is maintained through liming (hanging out) at cricket matches and social events. Speaking in their native Patois language, eating traditional Caribbean foods, and consuming alcohol are significant means of creating spaces in which Caribbean- Canadians can network with other members of the diaspora. -

24Th Annual Sir Garfield Sobers International Schools Tournament July 2010 Fixtures

24th Annual Sir Garfield Sobers International Schools Tournament July 2010 Fixtures Day 1 Mon 5th Zone A Phoenix Academy - Barbados VS. BCL - Barbados Carlton BYE Bermuda Development Dominica Combined Schools VS. Queen's Park Club Cricket Coaching School T & T Banks Bequia Community High School VS. Dulwich College - UK Bridgefeild Xenon Academy - Guyana VS. St Clair Dacon School - St Vincent Inch Marlow Zone B Oxley College - Australia VS. Lester Vaughan School - Barbados Briar Hall BYE Combermere - Barbados FourSquare Shenfield School - UK VS. BCC - Barbados Oval Corinth Secondary School - St.Lucia VS. St Mary's School - T & T YMPC Top Level Academy - Guyana VS. Presentation College - T & T Wayne Daniel Day 2 Tues 6th Zone A Xenon Academy - Guyana VS. Bequia Community High School James Bryan St Clair Dacon School - St Vincent VS. Dominica Combined Schools Content Bermuda Development VS. BCL - Barbados Wayne Daniel BYE Dulwich College - UK Phoenix Academy - Barbados VS. Queen's Park Club Cricket Coaching School T & T Briar Hall Zone B Oxley College - Australia VS. Shenfield School - UK Crab Hill BYE Corinth Secondary School - St.Lucia Combermere - Barbados VS. BCC - Barbados Banks Conrad Presentation College - T & T VS. St Mary's School - T & T Hunte Top Level Academy - Guyana VS. Lester Vaughan School - Barbados Hoytes Day 3 Wed 7th Zone B Oxley College - Australia VS. St Mary's School - T & T James Bryan Day 4 Thurs 8th Zone A Phoenix Academy - Barbados VS. Xenon Academy - Guyana Wayne Daniel Dominica Combined Schools BYE Bequia Community High School VS. BCL - Barbados Empire St Clair Dacon School - St Vincent VS. -

Race and Cricket: the West Indies and England At

RACE AND CRICKET: THE WEST INDIES AND ENGLAND AT LORD’S, 1963 by HAROLD RICHARD HERBERT HARRIS Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Arlington in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT ARLINGTON August 2011 Copyright © by Harold Harris 2011 All Rights Reserved To Romelee, Chamie and Audie ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My journey began in Antigua, West Indies where I played cricket as a boy on the small acreage owned by my family. I played the game in Elementary and Secondary School, and represented The Leeward Islands’ Teachers’ Training College on its cricket team in contests against various clubs from 1964 to 1966. My playing days ended after I moved away from St Catharines, Ontario, Canada, where I represented Ridley Cricket Club against teams as distant as 100 miles away. The faculty at the University of Texas at Arlington has been a source of inspiration to me during my tenure there. Alusine Jalloh, my Dissertation Committee Chairman, challenged me to look beyond my pre-set Master’s Degree horizon during our initial conversation in 2000. He has been inspirational, conscientious and instructive; qualities that helped set a pattern for my own discipline. I am particularly indebted to him for his unwavering support which was indispensable to the inclusion of a chapter, which I authored, in The United States and West Africa: Interactions and Relations , which was published in 2008; and I am very grateful to Stephen Reinhardt for suggesting the sport of cricket as an area of study for my dissertation. -

Cricket As a Catalyst for West Indian Independence: 1950-1962

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 8-21-2013 12:00 AM 'Massa Day Done:' Cricket as a Catalyst for West Indian Independence: 1950-1962 Jonathan A. Newman The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Don Morrow The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Kinesiology A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Arts © Jonathan A. Newman 2013 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Sports Studies Commons Recommended Citation Newman, Jonathan A., "'Massa Day Done:' Cricket as a Catalyst for West Indian Independence: 1950-1962" (2013). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 1532. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/1532 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ‘Massa Day Done:’ Cricket as a Catalyst for West Indian Independence, 1950-1962. Thesis format: Monograph by Jonathan Newman Graduate Program in Kinesiology A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Jonathan Newman 2013 Abstract This thesis examined the manner in which West Indies cricket became a catalyzing force for West Indians in moving towards political independence from Britain during the period 1950- 1962. West Indians took a game that was used as a means of social control during the colonial era, and refashioned that game into a political weapon to exact sporting and especially political revenge on their colonial masters. -

Next Issue: Washington Youth Cricket . Charlotte Int

Next Issue: Washington Youth Cricket . Charlotte Int. Cricket Club . Private Cricket Grounds 2 AMERICAN CRICKETER WINTER ISSUE 2009 American Cricketer is published by American Cricketer, Inc. Copyright 2009 Publisher - Mo Ally Editor - Deborah Ally Assistant Editor - Hazel McQuitter Graphic & Website Design - Le Mercer Stephenson Legal Counsel - Lisa B. Hogan, Esq. Accountant - Fargson Ray Editorial: Mo Ally, Peter Simunovich, ICC, Ricardo Innis, Colorado Cricket League, Erik Petersen Nino DiLoreto, Clarence Modeste, Peter Mc Dermott Major U.S. Distribution: New Jersey • Dreamcricket.com - Hillsborough Florida • All Major Florida West Indian Food Stores • Bedessee Sporting Goods - Lauderhill • Joy Roti Shop - Lauderhill • Tropics Restaurant - Pembroke Pines • The Hibiscus Restaurant - Lauderhill and Orlando • Caribbean Supercenter - Orlando • Timehri Restaurant - Orlando California • Springbok Bar & Grill - Van Nuys & Long Beach Colorado • Midwicket - Denver New York • Bedessee Sporting Goods - Brooklyn • Global Home Loan & Finance - Floral Park International Distribution: • Dubai, UAE • Auckland, New Zealand • Tokyo, Japan • Georgetown, Guyana, South America • London, United Kingdom • Victoria, British Columbia, Canada • Kingston, Jamaica, West Indies • Barbados, West Indies • Port-of-Spain, Trinidad & Tobago, West Indies • Sydney, Australia • Antigua, West Indies Mailing Address: P.O. Box 172255 Miami Gardens, FL 33017 Telephone: (305) 851-3130 E-mails: Publisher - [email protected] Editor - [email protected] Web address: www.americancricketer.com Volume 5 - Number 1 Subscription rates for the USA: Annual: $25.00 Subscription rates for outside the USA: Annual: $35.00 WINTER ISSUE 2009 WWW.AMERICANCRICKETER.COM 3 From the Publisher and the Editor In this issue Mo and Deborah Ally www.americancricketer.com American Cricketer and friends would like to extend our sympathy to cricketers and families in the tragedy at Lahore, Pakistan. -

The Big Three Era Starts

151 editions of the world’s most famous sports book WisdenEXTRA No. 12, July 2014 England v India Test series The Big Three era starts now Given that you can bet on almost anything these most recent book was a lovely biography of Bishan days, it would have been interesting to know the odds Bedi – a stylist who played all his international cricket on the first Test series under N. Srinivasan’s ICC before India’s 1983 World Cup win and the country’s chairmanship running to five matches. (Actually, on wider liberalisation. Since then, the IPL has moved the reflection, let’s steer clear of the betting issue.) But goalposts once again. Menon is in an ideal position to certainly, until this summer, many assumed that – examine what Test cricket means to Indians across the barring the Ashes – the five-Test series was extinct. Yet, social spectrum. here we are, embarking on the first since 2004-05 – The Ranji Trophy has withstood all this to remain when England clung on to win 2–1 in South Africa. the breeding ground for Indian Test cricketers. Although Not so long ago, five- or even six-match series it has never commanded quite the same affection as between the leading Test nations were the core of the the County Championship, it can still produce its fair calendar. Sometimes, when it rained in England or share of romance. We delve into the Wisden archives someone took an early lead in the subcontinent, the to reproduce Siddhartha Vaidyanathan’s account of cricket could be dreary in the extreme. -

Decolonisation and the Imperial Cricket Conference, 1947–1965: a Study in Transnational Commonwealth History?

Decolonisation and the Imperial Cricket Conference, 1947–1965: A Study in Transnational Commonwealth History? by Usha Iyer A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy at the University of Central Lancashire September 2013 Student Declaration Concurrent registration for two or more academic awards *I declare that while registered as a candidate for the research degree, I have not been a registered candidate or enrolled student for another award of the University or other academic or professional institution Material submitted for another award *I declare that no material contained in the thesis has been used in any other submission for an academic award and is solely my own work Signature of Candidate: Type of Award : PhD School : School of Sport, Tourism and the Outdoors Abstract The game of cricket is often discussed as an enduring legacy of the British Empire. This dissertation examines the response of the Imperial Cricket Conference (ICC) as the official governing body of ‘international’ men’s cricket to developments related to decolonisation of the British Empire between 1947 and 1965. This was a period of intense political flux and paradigmatic shifts. This study draws on primary sources in the form of records of ICC and MCC meetings and newspaper archives, and a wide-ranging corpus of secondary sources on the history of cricket, history of the Commonwealth and transnational perspectives on history. It is the contention of this dissertation that these cricket archives have hitherto not been exploited as commentary on decolonisation or the Commonwealth. Due attention is given to familiarising the reader with the political backdrop in the Empire and Commonwealth against which the ICC is studied.