The Development of an Archive of Explicit Stylistic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Savannah Scottish Games & Highland Gathering

47th ANNUAL CHARLESTON SCOTTISH GAMES-USSE-0424 November 2, 2019 Boone Hall Plantation, Mount Pleasant, SC Judge: Fiona Connell Piper: Josh Adams 1. Highland Dance Competition will conform to SOBHD standards. The adjudicator’s decision is final. 2. Pre-Premier will be divided according to entries received. Medals and trophies will be awarded. Medals only in Primary. 3. Premier age groups will be divided according to entries received. Cash prizes will be awarded as follows: Group 1 Awards 1st $25.00, 2nd $15.00, 3rd $10.00, 4th $5.00 Group 2 Awards 1st $30.00, 2nd $20.00, 3rd $15.00, 4th $8.00 Group 3 Awards 1st $50.00, 2nd $40.00, 3rd $30.00, 4th $15.00 4. Trophies will be awarded in each group. Most Promising Beginner and Most Promising Novice 5. Dancer of the Day: 4 step Fling will be danced by Premier dancer who placed 1st in any dance. Primary, Beginner and Novice Registration: Saturday, November 2, 2019, 9:00 AM- Competition to begin at 9:30 AM Beginner Steps Novice Steps Primary Steps 1. Highland Fling 4 5. Highland Fling 4 9. 16 Pas de Basque 2. Sword Dance 2&1 6. Sword Dance 2&1 10. 6 Pas de Basque & 4 High Cuts 3. Seann Triubhas 3&1 7. Seann Triubhas 3&1 11. Highland Fling 4 4. 1/2 Tulloch 8. 1/2 Tulloch 12. Sword Dance 2&1 Intermediate and Premier Registration: Saturday, November 2, 2019, 12:30 PM- Competition to begin at 1:00 PM Intermediate Premier 15 Jig 3&1 20 Hornpipe 4 16 Hornpipe 4 21 Jig 3&1 17 Highland Fling 4 22. -

Physical Education Dance (PEDNC) 1

Physical Education Dance (PEDNC) 1 Zumba PHYSICAL EDUCATION DANCE PEDNC 140 1 Credit/Unit 2 hours of lab (PEDNC) A fusion of Latin and international music-dance themes, featuring aerobic/fitness interval training with a combination of fast and slow Ballet-Beginning rhythms that tone and sculpt the body. PEDNC 130 1 Credit/Unit Hula 2 hours of lab PEDNC 141 1 Credit/Unit Beginning ballet technique including barre and centre work. [PE, SE] 2 hours of lab Ballroom Dance: Mixed Focus on Hawaiian traditional dance forms. [PE,SE,GE] PEDNC 131 1-3 Credits/Units African Dance 6 hours of lab PEDNC 142 1 Credit/Unit Fundamentals, forms and pattern of ballroom dance. Develop confidence 2 hours of lab through practice with a variety of partners in both smooth and latin style Introduction to African dance, which focuses on drumming, rhythm, and dances to include: waltz, tango, fox trot, quick step and Viennese waltz, music predominantly of West Africa. [PE,SE,GE] mambo, cha cha, rhumba, samba, salsa. Bollywood Ballroom Dance: Smooth PEDNC 143 1 Credit/Unit PEDNC 132 1 Credit/Unit 2 hours of lab 2 hours of lab Introduction to dances of India, sometimes referred to as Indian Fusion. Fundamentals, forms and pattern of ballroom dance. Develop confidence Dance styles focus on semi-classical, regional, folk, bhangra, and through practice with a variety of partners. Smooth style dances include everything in between--up to westernized contemporary bollywood dance. waltz, tango, fox trot, quick step and Viennese waltz. [PE,SE,GE] [PE,SE,GE] Ballroom Dance: Latin Irish Dance PEDNC 133 1 Credit/Unit PEDNC 144 1 Credit/Unit 2 hours of lab 2 hours of lab Fundamentals, forms and pattern of ballroom dance. -

Wilson Area School District Planned Course Guide

Board Approved April 2018 Wilson Area School District Planned Course Guide Title of planned course: Music Theory Subject Area: Music Grade Level: 9-12 Course Description: Students in Music Theory will learn the basics and fundamentals of musical notation, rhythmic notation, melodic dictation, and harmonic structure found in Western music. Students will also learn, work on, and develop aural skills in respect to hearing and notating simple melodies, intervals, and chords. Students will also learn how to analyze a piece of music using Roman numeral analysis. Students will be expected to complete homework outside of class and will be graded via tests, quizzes, and projects. Time/Credit for this Course: 3 days a week / 0.6 credit Curriculum Writing Committee: Jonathan Freidhoff and Melissa Black Curriculum Map August: ● Week 1, Unit 1 - Introduction to pitch September: ● Week 2, Unit 1 - The piano keyboard ● Week 3, Unit 1 - Reading pitches from a score ● Week 4, Unit 1 - Dynamic markings ● Week 5, Unit 1 - Review October: ● Week 6, Unit 1 - Test ● Week 7, Unit 2 - Dividing musical time ● Week 8, Unit 2 - Rhythmic notation for simple meters ● Week 9, Unit 2 - Counting rhythms in simple meters November: ● Week 10, Unit 2 - Beat units other than the quarter note and metrical hierarchy ● Week 11, Unit 2 - Review ● Week 12, Unit 2 - Test ● Week 13, Unit 4 - Hearing compound meters and meter signatures December: ● Week 14, Unit 4 - Rhythmic notation in compound meters ● Week 15, Unit 4 - Syncopation and mixing beat divisions ● Week -

![[BEGIN NICK LETHERT PART 01—Filename: A1005a EML Mmtc]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5265/begin-nick-lethert-part-01-filename-a1005a-eml-mmtc-175265.webp)

[BEGIN NICK LETHERT PART 01—Filename: A1005a EML Mmtc]

Nick Lethert Interview Narrator: Nick Lethert Interviewer: Dáithí Sproule Date: 1 December, 2017 DS: Dáithí Sproule NL: Nick Lethert [BEGIN NICK LETHERT PART 01—filename: A1005a_EML_mmtc] DS: Here we are – we are recording. It says “record” and the numbers are going up. This is myself and Nick Lethert making a second effort at our interview. It’s the first of December, isn’t it? NL: It is. DS: And we’re at the Celtic Junction. I suppose we’ll start at the same place as we started the last time, which was, I just think chronologically, and I think of, what is your background, what is the background of your father, your family, and origins, and your mother. NL: I grew up just down the street from the Celtic Junction in Saint Mark’s parish to a household where the first twelve or so years I lived with my father, who was of German Catholic heritage and my mother, who was Irish Catholic. Both of my mother’s parents came from Connemara. They met in Saint Paul, and I lived with my grandmother, who was from a little village, a tiny little village called Derroe, which is in Connemara over in the area by Carraroe, Costello, sort of bogland around there. My grandmother was a very intense person, not the least of which because her husband, who grew up in Maam Cross, a little further up in the mountains in Connemara, left her and the family when they had three young children, so it made for sort of a Dickens-like life for her and for her three kids, one of which was my mother. -

Children's Perceptions of Anacrusis Patterns Within Songs

----------------------Q: B ; ~~ett, P. D. (1992). Children's perceptions of anacrusis.......... patterns within songs.~ Texas.... Music Education Research. T. Tunks, Ed., 1-7. Texas Music Education Research - 1990 1 Children's Perceptions of Anacrusis Patterns within Songs Peggy D. Bennett The University of Texas at Arlington In order to help children become musically literate, music teachers have reduced the complexity of musical sound into manageable units or patterns for study. Usually, these patterns are then arranged into a sequence that presumes level of difficulty, and educators lead children through a curriculum based on a progression of patterns "from simple to complex." This practice of using a sequential, "patterned" approach to elementary music education in North America was embraced in 'the 1960's and 1970's when the methodologies of Hungarian, Zoltan Kodaly, and German, Carl Orff, were imported and introduced to American teachers, Touting the "sound before symbol" approach, these methods, for many teachers, replaced the notion of training students to recognize symbols, then to perform the sounds the symbols represented. For many teachers of young children, this era of imported methods reversed the way they taught music, and the organization of music into patterns for study was a monumental aspect of these changes. A "pattern" approach to music education is supported by speech and brain research which indicates that, even when iteJ:t1s are not grouped, individuals naturally process information by organizing it into patterns for retention and recall (Neisser, 1967; Buschke, 1976; Miller, 1956; Glanzer, 1976). Similar processing occurs when musical stimuli are presented (Cooper & Meyer, 1960; Mursell, 1937; Lerdahl & lackendoff, 1983, p. -

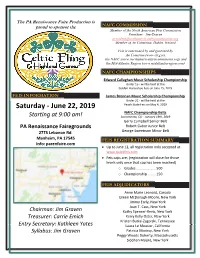

June 22, 2019

The PA Renaissance Faire Production is proud to sponsor the NAFC COMMISSION Member of the North American Feis Commission President: Jim Graven [email protected] Member of An Coimisiun, Dublin, Ireland Feis is sanctioned by and governed by An Comisiun (www.clrg.ie), the NAFC (www.northamericanfeiscommission.org) and the Mid-Atlantic Region (www.midatlanticregion.com) NAFC CHAMPIONSHIPS Edward Callaghan Music Scholarship Championship Under 15 - will be held at the Golden Horseshoe Feis on June 15, 2019 FEIS INFORMATION James Brennan Music Scholarship Championship Under 21 - will be held at the Peach State Feis on May 4, 2019 Saturday - June 22, 2019 NAFC Championship Belts Starting at 9:00 am! Sacramento, CA - January 19th, 2019 Gerry Campbell Senior Belt PA Renaissance Fairegrounds Robert Gabor Junior Belt 2775 Lebanon Rd. George Sweetnam Minor Belt Manheim, PA 17545 FEIS REGISTRATION SUMMARY Info: parenfaire.com Up to June 12, all registration only accepted at www.quickfeis.com Feis caps are: (registration will close for those levels only once that cap has been reached) o Grades ..................... 500 o Championship ......... 150 FEIS ADJUDICATORS Anne Marie Leonard, Canada Eileen McDonagh-Moore, New York Jimmy Early, New York Joan T. Cass, New York Chairman: Jim Graven Kathy Spencer-Revis, New York Treasurer: Carrie Emich Kerry Kelly Oster, New York Kristen Butke-Zagorski, Tennessee Entry Secretary: Kathleen Yates Laura Le Meusier, California Syllabus: Jim Graven Patricia Morissy, New York Peggy Woods Doherty, Massachusetts Siobhan Moore, New York COMPETITION FEES CELTIC FLING FEIS FESTIVAL Feis Admission includes ONE day ticket to the festival Competition Fees FEES (you can purchase a second day ticket at registration) Solo Dancing / TR / Sets / Non-Dance Kick-off concert on Friday featuring great performers! $ 10 Bring your appetite and enjoy delicious foods and (per competitor and per dance) refreshing wines, ales & ciders while listening to the live Preliminary Championship music! Gates open at 4PM. -

Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday

Pg 1 Vanda's Ballroom Classes. Pg 2 Different instructors for Belly Dancy and Irish Dance. For more info visit https://dancespotofdupage.com/ MARCH 2021 Unless marked otherwise, classes are beginner level. SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY 1 2 3 4 5 6 6:05-6:55 PM 6:05-6:55 PM Adult Ballet Advanced Waltz live or via Zoom Privates/ and Foxtrot Privates/ 7:05 - 7:55 PM Semi Privates Semi Privates NO CLASSES NO CLASSES Beginner Ballroom available 7:05 - 7:55 PM available Variety Interm Ballroom Variety 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 6:05-6:55 PM 6:05-6:55 PM Adult Ballet Advanced Waltz 6:05 - 6:55 PM live or via Zoom Privates/ and Foxtrot Privates/ Swing and Latin Privates/ NO CLASSES 7:05 - 7:55 PM Semi Privates Semi Privates Technique Semi Privates Beginner Ballroom available 7:05 - 7:55 PM available available Variety Interm Ballroom Variety 14 15 16 17 ST PATRICK'S DAY 18 19 20WELCOME SPRING! 6:05-6:55 PM Adult Ballet 6:05-6:55 PM 6:05 - 6:55 PM Privates/ live or via Zoom Privates/ Advanced Waltz Privates/ Swing and Latin Privates/ and Foxtrot Semi Privates 7:05 - 7:55 PM Semi Privates Semi Privates Semi Privates 7:05 - 7:55 PM Technique available Beginner Ballroom available available available Interm Ballroom Variety Variety 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 6:05-6:55 PM 6:05-6:55 PM Adult Ballet Advanced Waltz 6:05 - 6:55 PM Privates/ live or via Zoom Privates/ and Foxtrot Privates/ Swing and Latin Privates/ Semi Privates 7:05 - 7:55 PM Semi Privates Semi Privates Technique Semi Privates available Beginner Ballroom available 7:05 - 7:55 PM available available Variety Interm Ballroom Variety 28 29 30 31 6:05-6:55 PM 6:05-6:55 PM Adult Ballet Advanced Waltz Privates/ live or via Zoom Privates/ and Foxtrot 605 E. -

Radio 3 Listings for 30 May – 5 June 2009 Page

Radio 3 Listings for 30 May – 5 June 2009 Page 1 of 39 SATURDAY 30 MAY 2009 3.35am Vivaldi, Antonio (1678-1741): Nisi Dominus (Psalm 127), RV 608 SAT 01:00 Through the Night (b00klc29) Matthew White (countertenor) 1.00am Arte dei Suonatori Chopin, Fryderyk (1810-1849): Three pieces for piano Eduardo Lopez (conductor) 1.16am Beethoven, Ludwig van (1770-1827): Sonata quasi una fantasia 3.55am in C sharp minor for piano, Op 27, No 2 (Moonlight) Copi, Ambroz (b.1973): Psalm 108: My heart is steadfast Havard Gimse (piano) Chamber Choir AVE Andraz Hauptman (conductor) 1.31am Dvorak, Antonin (1841-1904): Song to the Moon (Rusalka, Op 4.00am 114) Arnic, Blaz (1901-1970): Suite about the well, Op 5 1.37am Slovenian Radio and Television Symphony Orchestra Grieg, Edvard (1843-1907): I Love Thee (Hjertets melodier, Op Lovrenc Arnic (conductor) 5) - arr Max Reger 1.39am 4.32am Coward, Noel (1899-1973): I'll follow my secret heart Paganini, Niccolo (1782-1840): Duetto amoroso (Conversation Piece) Tomaz Lorenz (violin) Yvonne Kenny (soprano) Jerko Novak (guitar) Melbourne Symphony Orchestra Vladimir Kamirski (conductor) 4.42am Bellini, Vincenzo (1801-1835): Vanne o rosa fortunate; Bella 1.44am Nice, che d'amore Strauss, Johann II (1825-1899): Wein, Weib und Gesang, arr Nicolai Gedda (tenor) Alban Berg for string quartet, piano and harmonium Miguel Zanetti (piano) Canadian Chamber Ensemble Raffi Armenian (conductor) 4.48am Berlioz, Hector (1803-1869): Overture: Waverley, Op 1 1.55am The Radio Bratislava Symphony Orchestra Kunzen, Friedrich (1761-1817): -

Billboard 1978-05-27

031ÿJÚcö7lliloi335U7d SPOTLIG B DALY 50 GRE.SG>=NT T HARTFJKJ CT UolOo 08120 NEWSPAPER i $1.95 A Billboard Publication The International Music -Record -Tape Newsweekly May 27, 1978 (U.S.) Japanese Production Tax Credit 13 N.Y. DEALERS HIT On Returns Fania In Court i In Strong Comeback 3y HARUHIKO FUKUHARA Stretched? TOKYO -March figures for By MILDRED HALL To Fight Piracy record and tape production in Japan WASHINGTON -The House NBC Opting underscore an accelerating pace of Ways and Means Committee has re- By AGUSTIN GURZA industry recovery after last year's ported out a bill to permit a record LOS ANGELES -In one of the die appointing results. manufacturer to exclude from tax- `AUDIO VIDISK' most militant actions taken by a Disks scored a 16% increase in able gross income the amount at- For TRAC 7 record label against the sale of pi- quantity and a 20% increase in value tributable to record returns made NOW EMERGES By DOUG HALL rated product at the retail level, over last year's March figures. And within 41/2 months after the close of By STEPHEN TRAIMAN Fania Records filed suit Wednesday NEW YORK -What has been tales exceeded those figures with a his taxable year. NEW YORK -Long anticipated, (17) in New York State Supreme held to be the radio industry's main 5S% quantity increase and a 39% Under present law, sellers of cer- is the the "audio videodisk" at point Court against 13 New York area re- hope against total dominance of rat- value increase, reports the Japan tain merchandise -recordings, pa- of test marketing. -

Barn Dance Square Dance Ceilidh Twmpath Contra Hoe Down 40'S

Paul Dance Caller and Teacher Have a look then get in touch [email protected] [email protected] Barn Dance 0845 643 2095 Local call rate from most land lines Square Dance (Easy level to Plus) Ceilidh Twmpath Contra Hoe Down 40’s Night THE PARTY EVERYONE CAN JOIN IN AND EVERYONE CAN ENJOY! So you are thinking of having a barn dance! Have you organised one before? If you haven't then the following may be of use to you. A barn dance is one of the only ways you can get everyone involved from the start. NO experience is needed to take part. Anyone from four to ninty four can join in. The only skill needed is being able to walk. All that is required is to be able to join hands in a line or a circle, link arms with another dancer, or join hands to make an arch. The rest is as easy as falling off a log. You dance in couples and depending on the type of dance you can dance in groups from two couples, four couples, and upwards to include the whole floor. You could be dancing in lines, in coloumns, in squares or in circles,. It depends on which dance the caller calls. The caller will walk everyone through the dance first so all the dancers know what the moves are. The caller will call out all the moves as you dance until the dancers can dance the dance on their own. A dance can last between 10 and 15 minutes including the walk through. -

August 2012 Newsletter

August 2012 Newsletter ------------------------------------ Yesterday & Today Records P.O.Box 54 Miranda NSW 2228 Phone: (02) 95311710 Email:[email protected] www.yesterdayandtoday.com.au ------------------------------------------------ Postage Australia post is essentially the world’s most expensive service. We aim to break even on postage and will use the best method to minimise costs. One good innovation is the introduction of the “POST PLUS” satchels, which replace the old red satchels and include a tracking number. Available in 3 sizes they are 500 grams ($7.50) 3kgs ($11.50) 5kgs ($14.50) P & P. The latter 2 are perfect for larger interstate packages as anything over 500 grams even is going to cost more than $11.50. We can take a cd out of a case to reduce costs. Basically 1 cd still $2. 2cds $3 and rest as they will fit. Again Australia Post have this ludicrous notion that if a package can fit through a certain slot on a card it goes as a letter whereas if it doesn’t it is classified as a “parcel” and can cost up to 5 times as much. One day I will send a letter to the Minister for Trade as their policies are distinctly prejudicial to commerce. Out here they make massive profits but offer a very poor number of services and charge top dollar for what they do provide. Still, the mail mostly always gets there. But until ssuch times as their local monopoly remains, things won’t be much different. ----------------------------------------------- For those long term customers and anyone receiving these newsletters for the first time we have several walk in sales per year, with the next being Saturday August 25th. -

Troubled Voices Martin Dowling a Troubles Archive Essay

Troubled Voices A Troubles Archive Essay Martin Dowling Cover Image: Joseph McWilliams - Twelfth March (1991) From the collection of the Arts Council of Northern Ireland About the Author Martin Dowling is a historian, sociologist, and fiddle player, and lecturer in Irish Traditional Music in the School of Music and Sonic Arts in Queen’s University of Belfast. Martin has performed internationally with his wife, flute player and singer Christine Dowling. He teaches fiddle regularly at Scoil Samhradh Willy Clancy and the South Sligo Summer School, as well as at festivals and workshops in Europe and America. From 1998 until 2004 he was Traditional Arts Officer at the Arts Council of Northern Ireland. He is the author of Tenant Right and Agrarian Society in Ulster, 1600-1870 (Irish Academic Press, 1999), and has held postdoctoral fellowships in Queen’s University of Belfast and University College Dublin. Recent publications include “Fiddling for Outcomes: Traditional Music, Social Capital, and Arts Policy in Northern Ireland,” International Journal of Cultural Policy, vol. 14, no 2 (May, 2008); “’Thought-Tormented Music’: Joyce and the Music of the Irish Revival,” James Joyce Quarterly, vol. 44, no. 1 (2008); and “Rambling in the Field of Modern Identity: Some Speculations on Irish Traditional Music,” Radharc: a Journal of Irish and Irish-American Studies, vols. 5-7 (2004-2006), pp. 109-136. He is currently working on a monograph history of Irish traditional music from the death of harpist-composer Turlough Carolan (1738) to the first performance of Riverdance (1994). Troubled Voices Street singers and pedlars of broadsheets had for two centuries been important figures in Irish political and social life.