Voting Rights for Prisoners

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cynulliad Cenedlaethol Cymru the National Assembly for Wales

Cynulliad Cenedlaethol Cymru The National Assembly for Wales Y Pwyllgor Menter a Busnes The Enterprise and Business Committee Dydd Iau, 27 Medi 2012 Thursday, 27 September 2012 Cynnwys Contents Cyflwyniad, Ymddiheuriadau a Dirprwyon Introductions, Apologies and Substitutions Sesiwn Ddiweddaru gyda’r Gweinidog Cyllid am Bolisi Caffael yr Undeb Ewropeaidd Update Session with the Minister for Finance on European Union Procurement Policy Sesiwn Ddiweddaru gyda’r Dirprwy Weinidog Amaethyddiaeth, Bwyd, Pysgodfeydd a Rhaglenni Ewropeaidd ynglŷn â Rhaglen Horizon 2020 a Chronfeydd Strwythurol yr UE Update Session with the Deputy Minister for Agriculture, Food, Fisheries and European Programmes Regarding the Horizon 2020 Programme and EU Structural Funds Cynnig Gweithdrefnol Procedural Motion Yn y golofn chwith, cofnodwyd y trafodion yn yr iaith y llefarwyd hwy ynddi. Yn y golofn dde, cynhwysir trawsgrifiad o’r cyfieithu ar y pryd. In the left-hand column, the proceedings are recorded in the language in which they were spoken. The right-hand column contains a transcription of the simultaneous interpretation. Aelodau’r pwyllgor yn bresennol Committee members in attendance 27/09/2012 Byron Davies Ceidwadwyr Cymreig Welsh Conservatives Yr Arglwydd/Lord Elis- Plaid Cymru Thomas The Party of Wales Julie James Llafur Labour Alun Ffred Jones Plaid Cymru The Party of Wales Eluned Parrott Democratiaid Rhyddfrydol Cymru Welsh Liberal Democrats Nick Ramsay Ceidwadwyr Cymreig (Cadeirydd y Pwyllgor) Welsh Conservatives (Committee Chair) Jenny Rathbone Llafur -

Annual Report and Financial Statement 2017

Cross-Party Group Annual Report. 2017-2018 Cross Party Group on Food Jenny Rathbone AM, David Melding AM, Jeremy Miles AM, Huw Irranca- Davies AM, Mike Hedges AM, Caroline Jones AM, Suzy Davies AM 1. Group membership and office holders. Jenny Rathbone AM (Chair) Secretary: To be elected at next meeting Other Outside Bodies Attending: Public Health Wales Cancer Research UK National Federation of Women’s Institutes (NFWI) Wales Tenovus Public Health Wales Food Waste Prevention Food Cardiff NHS Shared Services NHS Education Catering Cardiff and Vale UHB ABMU Health Board WRAP Cardiff and Vale Public Health Team NHS UNISON Local residents Frosty’s Green Grocers CLAS Cymru All Wales Nutrition University of South Wales Welsh Government Food Division Federation of City Farms & Community Gardens Exeter University Cardiff School of Geography and Planning Women’s Institute British Dietetic Association Annual Report Cross Party Group on Food 2017-2018 2. Previous Group Meetings. Meeting 1 Meeting date: 10th May 2017 Attendees: Jenny Rathbone AM Suzy Davies AM Huw Irranca Davies AM Christian Webb, Simon Thomas’ Office Jack Sellers, David Melding’s Office Bethan Proctor, Jenny Rathbone’s Office Peter Wong, Jenny Rathbone’s Office Amber Tatton, Jenny Rathbone’s Office Amber Wheeler, University of South Wales Katie Palmer, Food Cardiff David Morris, Welsh Government Emma Williams, Federation of City Farms & Community Gardens Rebecca Sandover, PhD student, Exeter University Dr. Ana Moragues Faus, Cardiff School of Geography and Planning Sarah Thomas, -

4.3 Presidential Government

11 MM VENKATESHWARA COMPARATIVE POLITICAL OPEN UNIVERSITY SYSTEMS www.vou.ac.in COMPARATIVE POLITICAL SYSTEMS POLITICAL COMPARATIVE COMPARATIVE POLITICAL SYSTEMS MA [POLITICAL SCIENCE] [MAPS-105] VENKATESHWARA OPEN UNIVERSITYwww.vou.ac.in COMPARATIVE POLITICAL SYSTEMS MA [Political Science] MAPS 105 BOARD OF STUDIES Prof Lalit Kumar Sagar Vice Chancellor Dr. S. Raman Iyer Director Directorate of Distance Education SUBJECT EXPERT Ms. Puppy Gyadi Assistant Professor CO-ORDINATOR Mr. Tauha Khan Registrar Authors Dr Biswaranjan Mohanty: Units (3.3, 6.2, 7.2-7.3) © Dr Biswaranjan Mohanty, 2019 Vikas Publishing House: Units (1, 2, 3.0-3.2, 3.4-3.10, 4, 5, 6.0-6.1, 6.3-6.9, 7.0-7.1, 7.4-7.9, 8, 9, 10) © Reserved, 2019 All rights reserved. No part of this publication which is material protected by this copyright notice may be reproduced or transmitted or utilized or stored in any form or by any means now known or hereinafter invented, electronic, digital or mechanical, including photocopying, scanning, recording or by any information storage or retrieval system, without prior written permission from the Publisher. Information contained in this book has been published by VIKAS® Publishing House Pvt. Ltd. and has been obtained by its Authors from sources believed to be reliable and are correct to the best of their knowledge. However, the Publisher and its Authors shall in no event be liable for any errors, omissions or damages arising out of use of this information and specifically disclaim any implied warranties or merchantability or fitness for any particular use. Vikas® is the registered trademark of Vikas® Publishing House Pvt. -

Sentencing and Immediate Custody in Wales: a Factfile

Sentencing and Immediate Custody in Wales: A Factfile Dr Robert Jones Wales Governance Centre at Cardiff University January 2019 Acknowledgements ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author would especially like to thank Lucy Morgan for all of her help in producing this report. I would also like to thank staff working at the Ministry of Justice who have responded to the many requests for information made during the course of this research. Finally, I am extremely grateful to Alan Cogbill, Emyr Lewis, Ed Poole, Huw Pritchard and Richard Wyn Jones for their insightful comments on an earlier draft of this report. ABOUT US The Wales Governance Centre is a research centre that forms part of Cardiff University’s School of Law and Politics undertaking innovative research into all aspects of the law, politics, government and political economy of Wales, as well the wider UK and European contexts of territorial governance. A key objective of the Centre is to facilitate and encourage informed public debate of key developments in Welsh governance not only through its research, but also through events and postgraduate teaching. In July 2018, the Wales Governance Centre launched a new project into Justice and Jurisdiction in Wales. The research will be an interdisciplinary project bringing together political scientists, constitutional law experts and criminologists in order to investigate: the operation of the justice system in Wales; the relationship between non-devolved and devolved policies; and the impact of a single ‘England and Wales’ legal system. CONTACT DETAILS Wales Governance Centre at Cardiff University, 21 Park Place, Cardiff, CF10 3DQ. Web: http://sites.cardiff.ac.uk/wgc/ ABOUT THE AUTHOR Robert Jones is a Research Associate at the Wales Governance Centre at Cardiff University. -

The Local Authorities (Conduct of Referendums) (Wales) Regulations 2008

EXPLANATORY MEMORANDUM TO THE LOCAL AUTHORITIES (CONDUCT OF REFERENDUMS) (WALES) REGULATIONS 2008 This Explanatory Memorandum has been prepared by the Local Government Policy Division and is laid before the National Assembly for Wales. PART 1 1. Description 1.1 This Instrument provides for the organisation of the holding of a referendum in a local authority in Wales to decide whether that authority should adopt a political structure involving (amongst others) a directly elected mayor. The Instrument provides for the questions to be put to the electorate, the publicity for a referendum, limits on expenditure, the conduct of the local authority concerned, plus the manner of voting, counting and matters connected with the register. 2. Matters of special interest to the Subordinate Legislation Committee 2.1 None. 3. Legislative Background 3.1 The powers enabling this Instrument to be made are contained in sections 45, 105 and 106 of the Local Government Act 2000. The functions of the National Assembly for Wales under these provisions have been transferred to the Welsh Ministers by virtue of section 162 of, and paragraph 30 of, Schedule 11 to the Government of Wales Act 2006. The Instrument is being made using the affirmative resolution procedure. 4. Purpose and intended effect of the legislation 4.1 This Instrument will revoke and replace, with appropriate amendments, The Local Authorities (Conduct of Referendums) (Wales) Regulations 2004 (SI No 870 (W.85)) (the 2004 Regulations). The principal changes made in these draft Regulations are to implement the changes made by the Electoral Administration Act 2006, which, inter alia, introduces measures to prevent electoral fraud. -

Cofnod Y Trafodion the Record of Proceedings

Cofnod y Trafodion The Record of Proceedings Y Pwyllgor Amgylchedd a Chynaliadwyedd The Environment and Sustainability Committee 22/10/2015 Trawsgrifiadau’r Pwyllgor Committee Transcripts Cynnwys Contents 4 Cyflwyniad, Ymddiheuriadau a Dirprwyon Introductions, Apologies and Substitutions 5 Ymchwiliad i ‘Dyfodol Ynni Callach i Gymru?’ Inquiry into ‘A Smarter Energy Future for Wales?’ 36 Ymchwiliad i ‘Dyfodol Ynni Callach i Gymru?’ Inquiry into ‘A Smarter Energy Future for Wales?’ 66 Cynnig o dan Reol Sefydlog 17.42 i Benderfynu Gwahardd y Cyhoedd o’r Cyfarfod Motion under Standing Order 17.42 to Resolve to Exclude the Public from the Meeting Cofnodir y trafodion yn yr iaith y llefarwyd hwy ynddi yn y pwyllgor. Yn ogystal, cynhwysir trawsgrifiad o’r cyfieithu ar y pryd. The proceedings are recorded in the language in which they were spoken in the committee. In addition, a transcription of the simultaneous interpretation is included. Aelodau’r pwyllgor yn bresennol Committee members in attendance Mick Antoniw Llafur Labour Jeff Cuthbert Llafur Labour Russell George Ceidwadwyr Cymreig Welsh Conservatives Llyr Gruffydd Plaid Cymru The Party of Wales Janet Haworth Ceidwadwyr Cymreig Welsh Conservatives Alun Ffred Jones Plaid Cymru (Cadeirydd y Pwyllgor) The Party of Wales (Committee Chair) Julie Morgan Llafur Labour William Powell Democratiaid Rhyddfrydol Cymru Welsh Liberal Democrats Jenny Rathbone Llafur Labour Eraill yn bresennol Others in attendance Chris Blake Cyfarwyddwr y Cymoedd Gwyrdd Director, The Green Valleys David Clubb Cyfarwyddwr, -

NORTH WALES Skills & Employment Plan 2019–2022

NORTH WALES Skills & Employment Plan 2019–2022 North Wales Regional Skills Partnership DRAFT (October 2019) Skills and Employment Plan 2019–2022 Foreword It is a pleasure to present our new Skills and Employment Plan for North Wales 2019– 2022. This is a three-year strategic Plan that will provide an insight into the supply and demand of the skills system in the region, and crucially, what employers are telling us are their needs and priorities. It is an exciting time for North Wales, with recent role in the education and skills system is central, positive figures showing growth in our and will continue to be a cornerstone of our employment rate and productivity. Despite this work. positive trajectory, there are many challenges, We have focussed on building intelligence on uncertainties and opportunities that lie ahead. the demand for skills at a regional and sectoral As a region, we need to ensure that our people level, and encouraged employers to shape the and businesses are able to maximise solutions that will enhance North Wales’ skills opportunities like the Growth Deal and performance. As well as putting forward technological changes, and minimise the priorities in support of specific sectors, the Plan impact of potential difficulties and also sets out the key challenges that face us uncertainties, like the risk of a no-deal Brexit. and what actions are needed to encourage a Skills are fundamental to our continuing change in our skills system. economic success. Increasingly, it is skills, not just The North Wales Regional Skills Partnership (RSP) qualifications that employers look for first. -

Written Response by WG

Agenda Item: 4 Meeting of: Democratic Services Committee Date of Meeting: Monday, 22 July 2019 Relevant Scrutiny Committee: Corporate Performance and Resources Written Response by the Welsh Government to the Report of the Equality, Report Title: Local Government and Communities Committee entitled Diversity in Local Government - April 2019 To apprise Members of the Minister for Housing and Local Government response to the Welsh Assembly Equality, Local Government and Purpose of Report: Communities Committees recommendations in relation to Diversity in Local Government Report Owner: Head of Democratic Services Responsible Officer: Jeff Rees Elected Member and This is an internal matter and, therefore, no consultation has been Officer Consultation: necessary. The Council will be required to abide with any changes required as a result of Policy Framework: any new statutory legislation. Executive Summary: • On Wednesday 26 June, the National Assembly for Wales debated the Equality, Local Government and Communities Committee (ELGCC) report on Diversity in Local Government. • The Committee made 22 recommendations in its report which were predominantly for the Welsh Government. These ranged from publicity campaigns to encourage greater diversity of candidates standing for election, to mock elections for young people to run concurrently with Assembly elections. Some of the Committee’s recommendations would require new and additional resources from the Welsh Government. • Set out at Appendix A, is a copy of the Minister's response to the Committee's recommendations. 1 Recommendation 1. That the recommendations of the Welsh Assembly Equality, Local Government and Communities Committee's recommendations in relation to Diversity in Local Government and the Minister's response be noted. -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Public

------------------------ Public Document Pack ------------------------ Public Accounts Committee Meeting Venue: Committee Room 3 - Senedd Meeting date: Tuesday, 10 February 2015 Meeting time: 09.00 For further information please contact: Michael Kay Committee Clerk 0300 200 6565 [email protected] Agenda 1 Introductions, apologies and substitutions (09:00) 2 Papers to note (09:00-09:05) (Pages 1 - 3) Intra-Wales - Cardiff to Anglesey - Air Service: Letter from James Price, Welsh Government (2 February 2015) (Pages 4 - 6) Committee Correspondence: Letter from the Auditor General for Wales to Eluned Parrott AM (4 February 2015) - Welsh Government Investment in Roath Basin (Pages 7 - 14) 3 Hospital Catering and Patient Nutrition: Written Update from the Welsh Government (09:05-09:15) (Pages 15 - 23) PAC(4)-05-15 Paper 1 - Professor Jean White - NHS Wales 4 Motion under Standing Order 17.42 to resolve to exclude the public from the meeting for the following business: (09:15) Item 5 and 6 5 Briefing from the Wales Audit Office on Managing Early Departures across Welsh Public Bodies (09:15-09:45) (Pages 24 - 83) PAC(4)-05-15 Paper 2 - Managing Early Departures across Welsh Public Bodies 6 Scrutiny of Accounts 2013-14: Consideration of Draft Report (09:45- 10:20) (Pages 84 - 127) PAC(4)-05-15 Paper 3 - Scrutiny of Accounts Draft Report Agenda Item 2 Public Accounts Committee Meeting Venue: Committee Room 3 - Senedd Meeting date: Tuesday, 3 February 2015 Meeting time: 09.00 - 11.00 This meeting can be viewed on Senedd TV at: http://senedd.tv/en/2604 -

Justice in Wales

Justice in Wales Dr Sarah Nason, Prifysgol Bangor University (May 2020) Contents: Summary………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..1 Chapter One: Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………………………..7 Chapter Two: Criminal Justice…………………………………………………………………………………………………8 2.1 Criminal justice at the ‘jagged edges’ of devolution………………………………………………8 2.2 Specific ‘jagged edge’ problems………………………………………………………………………….11 2.3 Managing complexity and the need for leadership……………………………………………..13 2.4 The need for improved evidenced based evaluation of policy initiatives; the need for more disaggregated Wales-only data…………………………………………………………….14 2.5 Scrutiny and accountability…………………………………………………………………………………15 Chapter Three: Administrative Justice………………………………………………………………………………….19 3.1 Public administrative law…………………………………………………………………………………….20 3.2 Administrative justice institutions……………………………………………………………………….23 3.3 ‘Jagged edges’ and oversight………………………………………………………………………………27 Chapter Four: Family Justice…………………………………………………………………………………………………28 4.1 Family justice: Introduction, key issues and oversight…………………………………………29 4.2 Cafcass Cymru…………………………………………………………………………………………………….30 4.3 Taking children into care…………………………………………………………………………………….30 4.4 Family Drug and Alcohol Courts (FDACs)…………………………………………………………….31 Chapter Five: Civil Justice……………………………………………………………………………………………………..32 Chapter Six: Information, Advice and Assistance, Including Legal Aid………………………………..…33 Chapter Seven: Funding for Justice in Wales………………………………………………………………………..35 Chapter Eight: -

Emergency Employment Proxy Vote Application Form

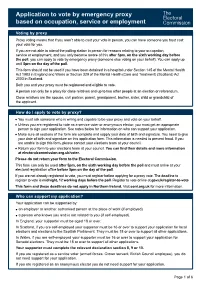

Application to vote by emergency proxy based on occupation, service or employment Voting by proxy Proxy voting means that if you aren’t able to cast your vote in person, you can have someone you trust cast your vote for you. If you are not able to attend the polling station in person for reasons relating to your occupation, service or employment, and you only become aware of this after 5pm, on the sixth working day before the poll, you can apply to vote by emergency proxy (someone else voting on your behalf). You can apply up until 5pm on the day of the poll. This form should not be used if you have been detained in a hospital under Section 145 of the Mental Health Act 1983 in England and Wales or Section 329 of the Mental Health (Care and Treatment) (Scotland) Act 2003 in Scotland. Both you and your proxy must be registered and eligible to vote. A person can only be a proxy for close relatives and up to two other people at an election or referendum. Close relatives are the spouse, civil partner, parent, grandparent, brother, sister, child or grandchild of the applicant. How do I apply to vote by proxy? You must ask someone who is willing and capable to be your proxy and vote on your behalf. Unless you are registered to vote as a service voter or anonymous elector, you must get an appropriate person to sign your application. See notes below for information on who can support your application. Make sure all sections of the form are complete and supply your date of birth and signature. -

(Anonymous Electors) Regulations 2008 No.2869

EXPLANATORY MEMORANDUM TO THE POLITICAL DONATIONS AND REGULATED TRANSACTIONS (ANONYMOUS ELECTORS) REGULATIONS 2008 2008 No. 2869 1. This explanatory memorandum has been prepared by the Ministry of Justice and is laid before Parliament by Command of Her Majesty. 2. Purpose of the instrument 2.1 The Regulations prescribe the form of evidence required from an elector who is registered anonymously in an electoral register who wishes to make a loan or donation to a political party. 3. Matters of special interest to the Select Committee on Statutory Instruments 3.1 None 4. Legislative Context 4.1 Political parties may only accept donations and loans from an individual if that person is registered in an electoral register. The Electoral Administration Act 2006 (c.22) established a framework for anonymous registration, allowing a registration officer to create an anonymous entry on the electoral register for a person whose safety, or that of people they live with, would be at risk if the register contained their name and address. The Representation of the People (England and Wales) Regulations 2001 (S.I.2001/341) and the Representation of the People (Scotland) Regulations 2001 (S.I.2001/497) provide that when a person has been entered on the register as an anonymous elector they are issued with a certificate of anonymous registration. The Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000 (c.41) provides that when reporting a donation or loan from an anonymously registered elector to the Electoral Commission a political party must state that it has seen evidence that the elector has an anonymous entry in the electoral register and provide a copy of that evidence.