CHAPTER 30 Department of Health and Environmental Control— Coastal Division

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boats and Harbors Publication 9-06

® $4.00 -and-har ats bo bo rs .c w. o w m BOATS & HARBORS w SECOND SEPTEMBER ISSUE 2019 VOLUME 62 NO. 13 Covering The East Coast, Gulf Coast, West Coast & Inland Waterways “THE” MARINE MARKETPLACE PH: (931) 484-6100 • Email: [email protected] Ok Bird Brain, there’ s the boat, let’ s see how your aim is.......people first, sails second, and new wax job third! BOATS AND HARBORS® P. O. Drawer 647 Crossville, TN 38557-0647 USA PAGE 2 - SECOND SEPTEMBER ISSUE 2019 See Us on the WEB at www.boats-and-harbors.com BOATS & HARBORS WANT VALUE FOR YOUR ADVERTISING DOLLAR? DENNIS FRANTZ • FRANTZ MARINE CORPORATION, INC. CELLULAR (504) 430-7117• Email: [email protected] • Email: [email protected] (ALL SPECIFICATIONS AS PER OWNER AND NOT GUARANTEED BY BROKER) 320' x 60' x 28 - Built 1995, 222' x 50' clear deck; U.S. flag. Over 38 Years in the Marine Industry Class: ABS +A1 +DP2. 280' L x 60' B x 24' D x 19' - loaded draft. Blt in 2004, US Flag, Class 1, +AMS, +DPS-2. Sub Ch. L & I. 203' x 50' clear deck. OSV’s - Tugs - Crewboats - Pushboats - Barges 272' L x 56' B x 18' D x 6' - light draft x 15' loaded draft. Built in 1998, Class: ABS +A1, +AMS, DPS-2. AHTS: 262' L x 58' B x 23' depth x 19' - loaded draft. Built in 195' x 35' x 10' 1998, Class: ABS + A1, Towing Vessel, AH (E) + AMS, DPS-2, SOLAS, US Flag. 260 L x 56 B x 18D x 6.60' - light draft x 15.20' loaded draft. -

Unali'yi Lodge

Unali’Yi Lodge 236 Table of Contents Letter for Our Lodge Chief ................................................................................................................................................. 7 Letter from the Editor ......................................................................................................................................................... 8 Local Parks and Camping ...................................................................................................................................... 9 James Island County Park ............................................................................................................................................... 10 Palmetto Island County Park ......................................................................................................................................... 12 Wannamaker County Park ............................................................................................................................................. 13 South Carolina State Parks ................................................................................................................................. 14 Aiken State Park ................................................................................................................................................................. 15 Andrew Jackson State Park ........................................................................................................................................... -

Winter/Spring 2013-2014

FRESPACE Findings Winter/Spring 2013/2014 President’s Report water is a significant shock to our animals and is a hindrance to our equipment cleaning efforts 2013 has certainly been a year of change for us: during maintenance. Susan Spell, our long serving ParkWinter 2008 Allocated $78 for FRESPACE to become Manager, left us early in the year to be near an ill a non-profit member of the Edisto Chamber of family member. This had consumed much of her Commerce. The Board feels that the expense is time over the previous year or so. We will miss justified based on the additional publicity EBSP her. and FRESPACE will receive from the Chamber’s Our new Park Manager, Jon Greider, many advertising initiatives. joined us during the summer. He has been most The ELC water cooler no longer works. helpful to us and we look forward to working The failure occurred during the recent hard with him. freeze. When the required repair is identified Our Asst. Park Manager, Jimmy “Coach” FRESPACE is prepared to help defray the costs. Thompson, retired late in Dec. He has always Authorized up to $150 to install pickets been there to help us and we are going to miss around the ELC rain barrels. Currently the “Coach”. barrels are unsightly and in a very visible area. Our new Asst. Park Manager, Brandon Goff, assumed his new duties shortly after the Our Blowhard team recently was in need of first of 2014. additional volunteers. Ida Tipton sent out an email Dan McNamee, our Interpretive Ranger blast from Bill Andrews, our Blowhard Team lead, over the last several years, left us in the early fall describing our needs as well as describing what to go to work at the Low Country Institute. -

Galveston, Texas

Galveston, Texas 1 TENTATIVE ITINERARY Participants may arrive at beach house as early as 8am Beach geology, history, and seawall discussions/walkabout Drive to Galveston Island State Park, Pier 21 and Strand, Apffel Park, and Seawolf Park Participants choice! Check-out of beach house by 11am Activities may continue after check-out 2 GEOLOGIC POINTS OF INTEREST Barrier island formation, shoreface, swash zone, beach face, wrack line, berm, sand dunes, seawall construction and history, sand composition, longshore current and littoral drift, wavelengths and rip currents, jetty construction, Town Mountain Granite geology Beach foreshore, backshore, dunes, lagoon and tidal flats, back bay, salt marsh wetlands, prairie, coves and bayous, Pelican Island, USS Cavalla and USS Stewart, oil and gas drilling and production exhibits, 1877 tall ship ELISSA Bishop’s Palace, historic homes, Pleasure Pier, Tremont Hotel, Galveston Railroad Museum, Galveston’s Own Farmers Market, ArtWalk 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS • Barrier Island System Maps • Jetty/Breakwater • Formation of Galveston Island • Riprap • Barrier Island Diagrams • Town Mountain Granite (Galveston) • Coastal Dunes • Source of Beach and River Sands • Lower Shoreface • Sand Management • Middle Shoreface • Upper Shoreface • Foreshore • Prairie • Backshore • Salt Marsh Wetlands • Dunes • Lagoon and Tidal Flats • Pelican Island • Seawolf Park • Swash Zone • USS Stewart (DE-238) • Beach Face • USS Cavalla (SS-244) • Wrack Line • Berm • Longshore Current • 1877 Tall Ship ELISSA • Littoral Zone • Overview -

SOUTH CAROLINA Our Land, Our Water, Our Heritage

SOUTH CAROLINA Our Land, Our Water, Our Heritage LWCF Funded Places in LWCF Success in South Carolina South Carolina The Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF) has provided funding to Federal Program help protect some of South Carolina’s most special places and ensure ACE Basin NWR recreational access for hunting, fishing and other outdoor activities. Cape Romain NWR South Carolina has received approximately $295 million in LWCF *Chattooga WSR funding over the past five decades, protecting places such as Fort Congaree NP Sumter National Monument, Cape Romain, Waccamaw and Ace Basin Cowpens NB National Wildlife Refuges, Congaree National Park, and Francis Marion Fort Sumter NM National Forest as well as sites protected under the Civil War Battlefield Francis Marion NF Preservation Program *Longleaf Pine Initiative Ninety Six NHS Sumter-Francis Marion NF Forest Legacy Program (FLP) grants are also funded under LWCF, to Sumter NF help protect working forests. The FLP cost-share funding supports Waccamaw NWR timber sector jobs and sustainable forest operations while enhancing wildlife habitat, water quality and recreation. For example, the FLP Federal Total $ 192,800,000 contributed to places such as the Catawba-Wateree Forest in Chester County and the Savannah River Corridor in Hampton County. The FLP Forest Legacy Program assists states and private forest owners to maintain working forest lands $ 39,400,000 through matching grants for permanent conservation easement and fee acquisitions, and has leveraged approximately $39 million in federal Habitat Conservation (Sec. 6) funds to invest in South Carolina’s forests, while protecting air and $ 1,700,000 water quality, wildlife habitat, access for recreation and other public American Battlefield Protection benefits provided by forests. -

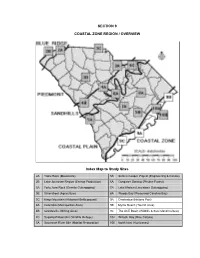

Coastal Zone Region / Overview

SECTION 9 COASTAL ZONE REGION / OVERVIEW Index Map to Study Sites 2A Table Rock (Mountains) 5B Santee Cooper Project (Engineering & Canals) 2B Lake Jocassee Region (Energy Production) 6A Congaree Swamp (Pristine Forest) 3A Forty Acre Rock (Granite Outcropping) 7A Lake Marion (Limestone Outcropping) 3B Silverstreet (Agriculture) 8A Woods Bay (Preserved Carolina Bay) 3C Kings Mountain (Historical Battleground) 9A Charleston (Historic Port) 4A Columbia (Metropolitan Area) 9B Myrtle Beach (Tourist Area) 4B Graniteville (Mining Area) 9C The ACE Basin (Wildlife & Sea Island Culture) 4C Sugarloaf Mountain (Wildlife Refuge) 10A Winyah Bay (Rice Culture) 5A Savannah River Site (Habitat Restoration) 10B North Inlet (Hurricanes) TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR SECTION 9 COASTAL ZONE REGION / OVERVIEW - Index Map to Coastal Zone Overview Study Sites - Table of Contents for Section 9 - Power Thinking Activity - "Turtle Trot" - Performance Objectives - Background Information - Description of Landforms, Drainage Patterns, and Geologic Processes p. 9-2 . - Characteristic Landforms of the Coastal Zone p. 9-2 . - Geographic Features of Special Interest p. 9-3 . - Carolina Grand Strand p. 9-3 . - Santee Delta p. 9-4 . - Sea Islands - Influence of Topography on Historical Events and Cultural Trends p. 9-5 . - Coastal Zone Attracts Settlers p. 9-5 . - Native American Coastal Cultures p. 9-5 . - Early Spanish Settlements p. 9-5 . - Establishment of Santa Elena p. 9-6 . - Charles Towne: First British Settlement p. 9-6 . - Eliza Lucas Pinckney Introduces Indigo p. 9-7 . - figure 9-1 - "Map of Colonial Agriculture" p. 9-8 . - Pirates: A Coastal Zone Legacy p. 9-9 . - Charleston Under Siege During the Civil War p. 9-9 . - The Battle of Port Royal Sound p. -

(J3+5Q I-’ /Fq.057 I I SENSITIVITY of COASTAL ENVIRONMENTS and WILDLIFE to SPILLED OIL ALAS KA - SHELIKOF STRAIT REGION

i (J3+5q i-’ /fq.057 I I SENSITIVITY OF COASTAL ENVIRONMENTS AND WILDLIFE TO SPILLED OIL ALAS KA - SHELIKOF STRAIT REGION - Daniel D. Domeracki, Larry C. Thebeau, Charles D. Getter, James L. Sadd, and Christopher H. Ruby Research Planning Institute, Inc. Miles O. Hayes, President 925 Gervais Street Columbia, South Carolina 29201 - with contributions from - Dave Maiero Science Applications, Inc. and Dennis Lees - Dames and Moore PREPARED FOR: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Outer Continental Shelf Environmental Assessment Program Juneau, Alaska RPI/R/81/2/10-4 Contract No. NA80RACO0154 February 1981 .i i . i ~hou~d read: 11; Caption !s Page 26, Figure four distinct biO1~~~cal rocky shore show~ng algae 2oner and P Exposed (1) barnacle (Balanus glandula) zone, zones: (3) -and ~~~e. blue mussel zone, ~ar-OSUsJ (4) barnacle ~B_ - . 27 -.--d. 29 ..-.A =~na beaches . 31 fixposed tidal flats (low biomass) . 33 Mixed sand and gravel beaches . 35 Gravel beaches . 37 Exposed tidal flats (moderate biomass) . 39 Sheltered rocky shores . ...*.. 41 Sheltered tidal flats . 43 Marshes ● =*...*. 45 Critical Species and Habitats . 47 Marine Mammals . ...*. 48 Coastal Marine Birds. 50 Finish . ...*.. 54 Shellfish . ...**.. ● *...... ...*.. ..* 56 Critical Intertidal Habitats . 58 Salt Marshes . 58 Sheltered Tidal Flats. 59 Sheltered Rocky Shores . 59 Critical Subtidal Habitats . 60 Nearshore Subtidal Habitats . ...*.. 60 Seagrass Beds . ...* ● . 62 Kelp Beds ● . ...**. ● .*...*. ...* . 63 ● . TABLE OF CONTENTS (continued) PAGE Discussion of Habitats with Variable to Slight Sensitivity. ...*..... 65 Introduction . 65 Exposed Rocky Shores. 65 Beaches . ● . 66 Exposed Tidal Flats.. 67 Areas of Socioeconomic Importance . 68 Mining Claims . 68 Private Property ● . 69 Public Property . ...*.. 69 Archaeological Sites. -

Container-‐On-‐Barge for Illinois Fueled by Biodiesel an Operating

Container-on-Barge for Illinois Fueled by Biodiesel An Operating Plan and Business Plan August 27, 2011 Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction and Overview ------------------------------------------------------------------- 4 2.0 Research/Investigation/Reports -------------------------------------------------------------------- 6 3.0 Lessons to Consider -------------------------------------------------------------------- 8 4.0 Inland Rivers Operations -------------------------------------------------------------------- 9 4.1 Ownership -------------------------------------------------------------------- 9 4.2 Towboats/Barges -------------------------------------------------------------------- 9 4.3 River Operations Modes -------------------------------------------------------------------- 10 4.4 The “Power Split” -------------------------------------------------------------------- 12 4.5 River Freight Pricing -------------------------------------------------------------------- 13 5.0 Designing Illinois COB -------------------------------------------------------------------- 15 5.1 Design Alternatives -------------------------------------------------------------------- 15 5.1.1 Purchased -------------------------------------------------------------------- 15 5.1.2 Leased -------------------------------------------------------------------- 18 5.1.3 Unit Tow -------------------------------------------------------------------- 19 6.0 Gulf COB – Cargo Flexibility -------------------------------------------------------------------- 21 7.0 COB Program -

Harbor Information

Vineyard Sound MV Land Bank Property * Keep our Waters Clean Moorings/Launch Service ad * eek Ro ing Cr Herr \ REMEMBER: All local waters are now a \ TISBURY TOWN MOORINGS are located insideWEST CHOP the VINEYARD Vineyard HAVEN Haven Harbor L (Town of a breakwater and can be rented on a first-come, first-servek basis. e Tisbury) NO DISCHARGE ZONE. T Drawbridge a s h m o o CONTACT THE HARBORMASTER ON CHANNEL 9. No Anchorage No Anchorage Heads must be sealed in all waters within 3 miles of shore and Moorings are 2-ton blocks on heavy chain and are maintained Channel Enlarged area Lagoon Pond the Vineyard Sound. regularly. They are to be used at boat owners’ risk. For ANCHORAGE, see map other side and/or consult the har- We provide FREE PUMPOUT service to mariners in Vineyard bormaster. Haven Harbor, Lagoon Pond and Lake Tashmoo. Call Vineyard o Haven pumpout on Channel 9 between 9 a.m. and 4 p.m., RUN GENERATING PLANTS AND ENGINE POWER o Anchorage seven days a week. EQUIPMENT BETWEEN 9 A.M. AND 9 P.M. ONLY. m I Ice * h R Repairs s Private moorings are available to rent from Gannon & WC NO PLASTICS OR TRASH OVERBOARD. Littering is MV Land Bank a Restrooms Property subject to a fine (up to $25,000 for each violation) and arrest. Benjamin, Maciel Marine, and the M.V. Shipyard or contact T Boat Ramp W Boaters must deposit trash only in the dumpsters and recy- Vineyard Haven Launch Service on Channel 72. e Water k dd Dinghy Dock cling bins at Owen Park and at Lake Street. -

National Register of Historic Places NATIONAL Multiple Property Documentation Form REGISTER

NFS Form 10-900-b . 0MB Wo. 1024-0018 (Jan. 1987) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service ,.*v Q21989^ National Register of Historic Places NATIONAL Multiple Property Documentation Form REGISTER This form is for use in documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Type all entries. A. Name of Multiple Property Listing________________________________________ Historic Resources of South Carolina State Parks________________________ B. Associated Historic Contexts_____________________________________________ The Establishment and Development of South Carolina State Parks__________ C. Geographical Data The State of South Carolina [_JSee continuation sheet D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60 and the Secretary of the Interior's Standards for Planning and Evaluation. Signature of gertifying official Date/ / Mary W. Ednonds, Deputy State Historic Preservation Officer, SC Dept. of Archives & His tory State or Federal agency and bureau I, heceby, certify that this multiple property documentation form has been approved by the National Register as a basis for ewalua|ing selaled properties for listing in the National Register. Signature of the Keeper of the National Register Date E. -

The Port of Portland's Marine Operations

The Port of Portland’s Marine Operations The Local Economic Benefits of Worldwide Trade Prepared for: August 2013 Contact Information Ed MacMullan, John Tapogna, Sarah Reich, and Tessa Krebs of ECONorthwest prepared this report. ECONorthwest is solely responsible for its content. ECONorthwest specializes in economics, planning, and finance. Established in 1974, ECONorthwest has over three decades of experience helping clients make sound decisions based on rigorous economic, planning and financial analysis. For more information about ECONorthwest, visit our website at www.econw.com. For more information about this report, please contact: Ed MacMullan Senior Economist 99 W. 10th Ave., Suite 400 Eugene, OR 97401 541-687-0051 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ...................................................................................................... ES-1 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1 2 Global Trade, Local Benefits ...................................................................................... 3 3 Intermodal Transportation Efficiencies .................................................................... 9 4 The Auto-Transport Story .......................................................................................... 10 5 The Potash Story ........................................................................................................ 12 6 The Portland Shipyard Story .................................................................................... -

Report on Survey of U.S. Shipbuilding and Repair Facilities 2001

Report on Survey of U.S. Department of Transportation Maritime U.S. Shipbuilding and Administration Repair Facilities 2001 REPORT ON SURVEY OF U.S. SHIPBUILDING AND REPAIR FACILITIES 2001 Prepared By: Office of Shipbuilding and Marine Technology December 2001 INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Introduction .......................................................................................................... 1 Overview of Major Shipbuilding and Repair Base ................................................ 5 Major U.S. Private Shipyards Summary Classification Definitions ....................... 6 Number of Shipyards by Type (Exhibit 1) ........................................................... 7 Number of Shipyards by Region (Exhibit 2) ........................................................ 8 Number of Shipyards by Type and Region (Exhibit 3) ........................................ 9 Number of Building Positions by Maximum Length Capability (Exhibit 4) ........... 10 Number of Build and Repair Positions (Exhibit 5) ............................................... 11 Number of Build and Repair Positions by Region (Exhibit 6) .............................. 12 Number of Floating Drydocks by Maximum Length Capability (Exhibit 7) .......... 13 Number of Production Workers by Shipyard Type (Exhibit 8) ............................. 14 Number of Production Workers by Region (Exhibit 9) ........................................ 15 Number of Production Workers: 1982 – 2001 (Exhibit 10) ................................. 16 Listing