An Enduring Spirit: the Photography of Thomas Merton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MASTER PLAN DOCUMENT.Indd

Master Plan for the RICHARDSON OLMSTED COMPLEX Buffalo, NY September 2009 9.29.09 Prepared For: THE RICHARDSON CENTER CORPORATION By: CHAN KRIEGER SIENIEWICZ CKS ARCHITECTURE AND URBAN DESIGN in collaboration with: Richardson Center Corporation (RCC) Richardson Architecture Center, Inc Reed Hilderbrand *Stanford Lipsey, Chairman Peter J. Atkinson - Capital Projects Manager, Landscape Architecture Publisher, The Buffalo News Harvard University Art Museums Watertown, MA *Howard Zemsky, Vice Chairman Anthony Bannon - Director, Urban Design Project President, Taurus Capital Partners, LLC. George Eastman House Public Process URBAN DESIGN PROJECT Buffalo, NY *Christopher Greene, Secretary Barbara A. Campagna, FAIA, LEED AP - Graham Gund Architect of the Partner, Damon & Morey, LLP National Trust for Historic Preservation City Visions/ City Properties Real Estate Development *Paul Hojnacki, Treasurer Brian Carter, Ex Offi cio - Dean and Professor, Louisville, KY President, Curtis Screw Company University at Buffalo School of Architecture and Planning Clarion Associates Carol Ash, Commissioner Louis Grachos - Director, Economic Modeling NYS Offi ce of Parks, Recreation, and Historic Preservation Albright-Knox Art Gallery Chicago, Il *Clinton Brown, President Robert Kresse – Attorney, Parsons Brinckerhoff Clinton Brown Co. Architecture, PC Hiscock & Barclay, LLP Permitting Buffalo, NY Paul Ciminelli, President & CEO Lynn J. Osmond - President and CEO, Ciminelli Development Company Chicago Architecture Foundation Bero Architecture Historic Preservation -

James Skalman, M.F.A

JAMES SKALMAN work tel: 619.849.2618 fax: 619.849.7033 email: [email protected] website: www.jamesskalman.com EDUCATION 1984 Master of Fine Arts, Painting/Sculpture University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, 1981 Bachelor of Arts, Painting/Printmaking San Diego State University TEACHING EXPERIENCE 1991 - present Point Loma Nazarene University, Professor Department of Art and Design, Chair 2000-2012 1986 - 1991 San Diego State University, Adjunct Instructor 1986 - 1987 Grossmont College, Visiting Instructor 1982 - 1984 University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill , Graduate T.A. SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2012-13 Las Vistas, a site-specific installation commissioned by San Diego State University for the SDSU downtown Gallery, San Diego, California 2001 Sudan Interior Mission: SNOW, a site-specific installation commissioned by BIOLA University, Los Angeles, California 1998 Water Level, an outdoor site-specific sculpture on the campus of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill 1995-96 "Samuel...?" , an installation, commissioned by the Museum of Contemporary Art, San Diego 1994-95 La Torre, an installation, commissioned by Installation Gallery as part of " inSITE94 " , La Torre de Tijuana , Tijuana, B.C. , Mexico 1991 Side Pockets, David Lewinson Gallery, Del Mar, CA. 1989 Field Plug, an installation commissioned by the University Gallery, University of Massachusetts at Amherst 1989 Hall, an outdoor sculptural project commissioned by Artpark, Lewiston, New York. 1988 Containment, an installation commissioned by the La Jolla Museum of Contemporary -

Education 2014 Virginia Commonwealth University, MFA

Erika Diamond 66 Panorama Dr., Asheville, NC 28806, 704.575.1493, [email protected] Education 2014 Virginia Commonwealth University, MFA Fiber 2000 Rhode Island School of Design, BFA Sculpture 1998 Edinburgh College of Art, The University of Edinburgh, Independent Study/Exchange Residencies 2019 UNC Asheville STEAM Studio, Asheville, NC 2018 Studio Two Three, Richmond, VA 2018 Platte Forum, Denver, CO 2016 ABK Weaving Center, Milwaukee, WI 2016 STARworks Center for Creative Enterprise, Star, NC 2014 Black Iris Gallery, Richmond, VA 2011 McColl Center for Visual Art, Charlotte, NC 2006-10 Little Italy Peninsula Arts Center, Mount Holly, NC 2006 McColl Center for Visual Art, Charlotte, NC Awards and Grants 2020 Artist Support Grant, Haywood County Arts Council, Waynesville, NC Artist Relief Grant, United States Artists, Chicago, IL Special Project Grant, Fiber Art Now, East Freetown, MA Mecklenburg Creatives Resiliency Grant, Arts & Science Council, NC 2019 American Craft Council, Conference Equity Award, Philadelphia, PA 2017 Adjunct Faculty Grant, VCU, School of the Arts, Richmond, VA 2016 American Craft Council, Conference Scholarship, Omaha, NE 2015 Regional Artist Project Grant, Arts & Science Council, Charlotte, NC 2014 VCU Arts Graduate Research Grant, VCU, Richmond, VA 2013 Graduate Assistantship Award, VCU, School of the Arts, Richmond, VA 2012 Graduate Assistantship Award, VCU, School of the Arts, Richmond, VA 2008 Cultural Project Grant, Arts & Science Council, Charlotte, NC 1996-20 RISD Alumni Scholarship, RISD, Providence, RI 1998-19 Leslie Herman Young Scholarship, RISD Sculpture Department, Providence, RI Exhibitions 2021 Armor, Center for Visual Art, Denver, CO (forthcoming) Amplify, Virginia Museum of Contemporary Art, Virginia Beach, VA (forthcoming) Summer Workshop Faculty Exhibition, Appalachian Center for Craft, Smithville, TN Imminent Peril – Queer Collection (Solo), Iridian Gallery, Richmond, VA Family Room, Form & Concept Gallery, Santa Fe, NM Queer Threads, Katzen Art Center, American University, Washington, D.C. -

The History of Photography: the Research Library of the Mack Lee

THE HISTORY OF PHOTOGRAPHY The Research Library of the Mack Lee Gallery 2,633 titles in circa 3,140 volumes Lee Gallery Photography Research Library Comprising over 3,100 volumes of monographs, exhibition catalogues and periodicals, the Lee Gallery Photography Research Library provides an overview of the history of photography, with a focus on the nineteenth century, in particular on the first three decades after the invention photography. Strengths of the Lee Library include American, British, and French photography and photographers. The publications on French 19th- century material (numbering well over 100), include many uncommon specialized catalogues from French regional museums and galleries, on the major photographers of the time, such as Eugène Atget, Daguerre, Gustave Le Gray, Charles Marville, Félix Nadar, Charles Nègre, and others. In addition, it is noteworthy that the library includes many small exhibition catalogues, which are often the only publication on specific photographers’ work, providing invaluable research material. The major developments and evolutions in the history of photography are covered, including numerous titles on the pioneers of photography and photographic processes such as daguerreotypes, calotypes, and the invention of negative-positive photography. The Lee Gallery Library has great depth in the Pictorialist Photography aesthetic movement, the Photo- Secession and the circle of Alfred Stieglitz, as evidenced by the numerous titles on American photography of the early 20th-century. This is supplemented by concentrations of books on the photography of the American Civil War and the exploration of the American West. Photojournalism is also well represented, from war documentary to Farm Security Administration and LIFE photography. -

PHSC News Vol 18-01

VOLUME 18-01, MAY 2018 FITNECESSITY IN THIS ISSUE Fitnecessity .......................... 1 PHSC Presents .................... 2 Photo Book 101 .................. 3 Spring Camera Fair ............ 4 Photos With Fix ................... 5 Equipment Review .............. 6 WebLinks .............................. 7 PHSC Events........................ 8 Bets for Contact .................. 9 Up until the twentieth century, peoples of most nations, Western or not, actually Ask Phinny .........................10 spent their days in prolonged physical activity. Farming, hunting, daily survival and even early industrialization required extensive human exertion. To complicate Classifieds ..........................11 matters, a longstanding class-based view of labour as demeaning which trickled down to a steadily growing middle and mercantile class, created a negative psychosocial meaning for exercise. As various means of saving labour slowly became the norm, questions about maintaining national strength with a population PHSC NEWS growing weak on ‘soft’ occupations began to rise. Writers such as H.G. Wells Editor - Sonja Pushchak (1866-1946) offered a bleak picture of labour avoidance with novels like The Time Distribution - David Bridge Machine (1895). In it, the delicate and helpless Eloi race, insinuated as ancestors of Contributors - David Bridge, the coddled Victorian upper class, were literally food for the Morlocks, the powerful Louise Freyburger, John Morden but monstrous descendents of the labouring classes. Secular and religious associations sprang up in Europe to meet the challenge of making citizens physically fit. Sweden got a head start with Per Henrik Ling (1776-1839), a pioneer in seeing the advantages of exercise. But it wasn’t until the economical marriage of photographic techniques and printing technology [email protected] that the information became broadly accessible. The images above, published in www.phsc.ca Schwedische Haus-Gymnastik nach dem System P.H. -

Public/Private

PUBLIC/PRIVATE Pairings with Works from the GERALD MEAD COLLECTION Bruce Adams, Charles Agel, Charlotte Albright, Laylah Ali, James Allen, Frank Altamura, Francisco Amaya, Neils Yde Andersen, Reed Anderson, David Andree, Steven Andresen, Cory Arcangel, Peter Arvidson, Rita Argen Auerbach Robert Baeumler, Sara Baker-Michalak, Vincent Baldassano, John Baldessari, Carol Barclay, Stefani Bardin, George Barker, Shelby Baron, Michael Basinski, Steve Baskin, Patricia Layman Bazelon, Howard Beach, Raphael Beck, Mary Begley, Michael Beitz, Sylvie Bélanger, Nancy Belfer, Larry Bell, Roberley Bell, Eric Bellmann, Sheldon Berlyn, Diane Bertolo, Amanda Besl, Charles Bigelow, Edward Bisone, Mark Bizub, Marvin Bjurlin, A. R. Blabac, Jeanette Blair, Robert Blair, Donald Blumberg, Joseph Bochynski, Malcolm Bonney, Robert Booth, Priscilla Bowen, Joel Brenden, Harvey Breverman, Alfred Briggs, Lawrence Brose, Bliss Brothers, Mia Brownell, AnJanette Brush, Barbara Buckman, Robert Budin, Paulo Buennos, Charles Burchfield, Philip Burke, Diane Bush, Scott Bye, Law rence Calcagno, Daniel Calleri, George Campos, Bill Cannon, Paul Francis Canorro, Ellen Carey, Jay Carrier, Patri cia Carter, Carla Castellani, Wendell Castle, Nicholas Chaltas, Sapphira Charles, Carl Chiarenza, Lori Christmas tree, John Chmura, George Merritt Clark, Charles Clough, Ethelyn Pratt Cobb, Adele Cohen, William Cooper, Lukia Costello, Veronique Cote, Matthew Crane, Annie Crawford, Robert Creeley, Frances Crohn, Colleen Cunningham, Bill Currie, George Curtis, D’Arcy Curwen, Val Cushing, Yolanda Daliz, Thomas Aquinas Daly, Allan D’Arcangelo, Peter D’Arcangelo, Kara Daving, Ethel M. C. Davis, Alfred Dixon, Marion Dodds, Russell Drisch, Seymour Drumlevitch, Brian Duffy, Donna Jordan Dusel, Nancy Dwyer, Eugene Dyczkowski, Frank Eckmair, Virginia Cuthbert Elliott, Philip Elliott, Andrew Engel, Hal English, Robbie Evans, Al Harris F., Marion Faller, Ami Farnham, Jackie Felix, Donna Fierle, Robert Finn, Robert Flock, Hollis Frampton, Pamela Frandina-Meheran, William Carson Francis, Mark Freeland, A. -

Roger Ballen Nominert Til Lucie Awards

18-10-2010 09:46 CEST Roger Ballen nominert til Lucie Awards Roger Ballen´s utstilling 'Photographs 1982-2009' kuratert av Dr Anthony Bannon for George Eastman House i New York er én av 5 nominerte i klassen 'årets kurator/utstilling' i den prestisjefulle Lucie Awards som deles ut i New York 27. Oktober 2010. Roger Ballens utstilling vises på Stenersen Museet i Oslo frem til 23. januar 2010. CURATOR/EXHIBITION OF THE YEAR -ENGAGED OBSERVERS:DOCUMENTARY PHOTOGRAPHY SINCE THE 60'S CURATED BY BRETT ABBOTT AT THE J PAUL GETTY MUSEUM, LOS ANGELES. - THE MODERN CENTURY CURATED BY PETER GALASSI FOR MUSEUM OF MODERN ART (MOMA), NEW YORK. EXPOSED: VOYERUSIM, SURVEILLANCE AND THE CAMERA CURATED BY SANDRA S. PHILLIPS FOR FOR TATE MODERN, LONDON. MEXICAN SUITCASE CURATED BY CYNTHIA YOUNG FOR INTERNATIONAL CENTER OF PHOTOGRAPHY. ROGER BALLEN: PHOTOGRAPHS 1982 - 2009 CURATED BY THE DR. ANTHONY BANNON FOR THE GEORGE EASTMAN HOUSE, NEW YORK. THE ADVISORY BOARD IS COMPRISED OF INDIVIDUALS RESPONSIBLE FOR IDENTIFYING AND NOMINATING EACH YEAR'S ROUND OF MASTER PHOTOGRAPHERS WHO WILL RECEIVE LUCIE AWARDS. The following individuals sit on the Lucie Award Advisory Board: Anthony Bannon, Director The George Eastman House, New York Nailya Alexander, Curator Nailya Alexander Gallery, New York Darsie Alexander, Curator Baltimore Museum, Baltimore Susan Aurinko, Director Flatfile Galleries, Chicago Kimberly Ayl, President Icon International, Los Angeles Bill Becker, Curator The American Museum of Photography Joseph Bellows, Curator Joseph Bellows Gallery, La Jolla -

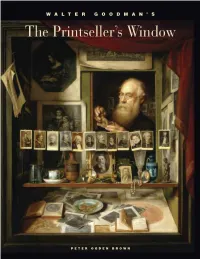

The Printseller's Window: Solving a Painter's Puzzle, on View at the Memorial Art Gallery of the University of Rochester from August 14–November 8, 2009

WALTER GOODMAN’S WALTER GOODMAN’S The Printseller’s Window The Printseller’s Window PETER OGDEN BROWN PETER OGDEN BROWN WALTER GOODMAN’S The Printseller’s Window PETER OGDEN BROWN 500 University Avenue, Rochester NY 14607, mag.rochester.edu Author: Peter O. Brown Editor: John Blanpied Project Coordinator: Marjorie B. Searl Designer: Kathy D’Amanda/MillRace Design Associates Printer: St. Vincent Press First published 2009 in conjunction with the exhibition Walter Goodman’s The Printseller’s Window: Solving a Painter’s Puzzle, on view at the Memorial Art Gallery of the University of Rochester from August 14–November 8, 2009. The exhibition was sponsored by the Thomas and Marion Hawks Memorial Fund, with additional support from Alesco Advisors and an anonymous donor. ISBN 978-0-918098-12-2 (alk. paper) ©2009 Memorial Art Gallery of the University of Rochester. All rights reserved. Except as permitted under current legislation, no part of this work may be photocopied, stored in a retrieval system, published, performed in public, adapted, broadcast, transmitted, recorded, or reproduced in any form or by any means, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. Every attempt has been made to identify owners of copyright. Errors or omissions will be corrected in subsequent editions. Cover illustration: Walter Goodman (British, 1838–1912) The Printseller’s Window, 1883 Oil on canvas 52 ¼” x 44 ¾” Marion Stratton Gould Fund, 98.75 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My pursuit of the relatively unknown Victorian painter Walter Goodman and his lost body of work began shortly after the Memorial Art Gallery’s acquisition of The Printseller’s Window1 in 1998. -

2010 George Eastman House Exhibitions

2010 George Eastman House Exhibitions What We're Collecting Now: Colorama The Family Photographed Curated by Jessica Johnston Curated by George Eastman House/Ryerson June 19–October 17 University Photographic Preservation & Collections Management students Jennie McInturff, Rick What We're Collecting Now: Art/Not-Art Slater, Jacob Stickann, Emily Wagner, and Andrew Curated by George Eastman House/Ryerson Youngman University Photographic Preservation & Collections September 5, 2009-July 18, 2010 Management students Jami Guthrie, Emily McKibbon, Loreto Pinochet, Paul Sergeant, D’arcy Where We Live White, and Soohyun Yang Curated by Alison Nordström, Todd Gustavson, July 24–October 24 Kathy Connor, Joseph R. Struble, Caroline Yeager, Jessica Johnston, and Jamie M. Allen Taking Aim: Unforgettable Rock ’n’ Roll October 3, 2009-February 14, 2010 Photographs Selected by Graham Nash October 30–January 30, 2011 How Do We Look Curated by Alison Nordström and Jessica Johnston All Shook Up: Hollywood and the Evolution of October 17, 2009-March 14, 2010 Rock ’n’ Roll Curated by Caroline Frick Page Roger Ballen: Photographs 1982–2009 October 30–January 16, 2011 Curated by Anthony Bannon February 27–June 6 Machines of Memory: Cameras from the Technology Collection Portrait Curated by Todd Gustavson Curated by Jamie M. Allen Ongoing February 27–October 17 The Remarkable George Eastman Persistent Shadow: Curated by Kathy Connor and Rick Hock Considering the Photographic Negative Ongoingz Curated by Jessica Johnston and Alison Nordström March 20–October -

James Blue, Buffalo, and the Complex Urban Documentary

The Wor ames Blue CONTENTS Acknowledgements Anthony Bannon excerpts from an Interview with James Blue Gerald O'Grady 12 -20 James Blue's Octagon Elmer Ploetz ,., ..- . 21 -23 James Blue and the Complex Urban Documentary Credits Thursday, October 13, 6:30 - 9 p.m. at Burchfield Penney AN OVERVIEW OF BLUE'S WORK 6:30 - 9 p.m. Reception and overview of James Blue's Career, including screenings and discussions of Blue's early work, rise, and influence Friday, October 14, the Center for the Fine Arts, rm. 112, UB North Campus at 7 p.m. USIA & JAMES BLUE THE SCHOOL AT RINCON SANTO, COLUMBIA (1962, 10 min., 16mm) A FEW NOTES ON OUR FOOD PROBLEM (1968,35min.,16mm) Documentary about the world's food crisis. Nominated for an Academy Award in 1968. THE MARCH TO WASHINGTON (1963-64,33 min., 16mm) Documentary about the historic Civil Rights March on Washington. Saturday, October 15 at 2 p.m. at the Burchfield-Penney Art Center VIDEO AND THE CITY WHO KILLED THE FOURTH WARD? (1 hr. excerpt, 1976177) INVISIBLE CITY (1 hr. 1979) discussion with producer Lynn Corcoran Saturday, October 15 at 7 p.m. at the Market Arcade Film &Arts Centre INTERNATIONAL ACCLAIM :BLUE'S APPROACH TO WAR IN ALGERIA AMAL (1960,21 rnin, 16 mm) A short film about land development and farming in Algeria. OLIVE TREES OF JUSTICE (1962,90 rnin., 16mm) Blue's only feature film, which received the Critics Prize at the Cannes Film Festival. Sunday, October 16, 1 pm at Burchfield-Penney Art Center BLUE AND ETHNOGRAPHIC FILM KENYA BORAN PARTS I & II (with David MacDougal, 1974,66 min. -

AFTER ATGET: TODD WEBB PHOTOGRAPHS NEW YORK and PARIS

e.RucSCHOELCHERanglcB'PAS a 'ihi\elU'S(k'h,iil(n e. hni • AFTER ATGET: DANTOM^79 TODD WEBB OUS PERMi T AFTER ATGET: TODD WEBB PHOTOGRAPHS NEW YORK and PARIS DIANA TUITE INTRODUCTION byBRITTSALVESEN BOWDOIN COLLEGE MUSEUM OF ART BRUNSWICK, MAINE This catalogue accompanies the COVER Fig. 26 (detail): exhibition A/Tt-rAf^ff; Todd Webb Todd Webb (American, 1905-2000) Photographs New York and Paris Rue Alesia, Paris (Oscar billboards), 1951 on view from October 28, 2011 through Vintage gelatin silver print January 29, 2012 at Bowdoin College 4x5 inches Museum of Art. Evans Gallery and Estate of Todd and Lucille Webb The exhibition and catalogue are generously supported by the PAGES 2-3 Fig. 1 (detail): Todd Webb Stevens L. Frost Endowment Fund, Harlem, NY (5 boys leaning on fence), 1946 the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation, Vintage gelatin silver print the Estate of Todd and Lucille Webb, 5x7 inches and Betsy Evans Hunt and Evans Gallery and Christopher Hunt. Estate of Todd and Lucille Webb Bowdoin College Museum of Art PHOTOGRAPHY CREDITS 9400 College Station Bowdoin College Museum of Art, Brunswick, Maine 04011 Brunswick, Maine, Digital Image © Pillar 207-725-3275 Digital Imaging: Figs. 4, 15, 28 © Berenice www.bowdoin.edu/art-museum Abbott / Commerce Graphics, NYC: 15, © Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Designer: Katie Lee Museum of Art, New York, NY: 28 New York, New York Evans Gallery and Estate of Todd and Editor: Dale Tucker Lucille Webb, Portland, Maine © Todd Webb, Courtesy of Evans Gallery Printer: Penmor Lithographers and Estate of Todd and Lucille Webb, Lewiston, Maine Portland, Maine USA, Digital Image © Pillar Digital Imaging: Figs. -

George Eastman Museum Annual Report 2019

George Eastman Museum Annual Report 2019 Contents Exhibitions 2 Traveling Exhibitions 3 Film Series at the Dryden Theatre 4 Programs & Events 5 Online 7 Education 8 The L. Jeffrey Selznick School of Film Preservation 8 Photographic Preservation & Collections Management 8 Photography Workshops 9 Loans 10 Object Loans 10 Film Screenings 14 Acquisitions 15 Gifts to the Collections 15 Photography 15 Moving Image 18 Technology 19 George Eastman Legacy 20 Richard and Ronay Menschel Library 25 Purchases for the Collections 25 Photography 25 Moving Image 26 Technology 26 George Eastman Legacy 26 Richard and Ronay Menschel Library 26 Conservation & Preservation 27 Conservation 27 Photography 27 Moving Image 29 Technology 30 Eastman Legacy 30 Richard and Ronay Menschel Library 30 Film Preservation 30 Financial 31 Treasurer’s Report 31 Statement of Financial Position 32 Statement of Activities and Change in Net Assets 33 Fundraising 34 Members 34 Corporate Members 36 Annual Campaign 36 Designated Giving 37 Planned Giving 40 Trustees, Advisors & Staff 41 Board of Trustees 41 George Eastman Museum Staff 42 George Eastman Museum, 900 East Avenue, Rochester, NY 14607 Exhibitions Exhibitions on view in the museum’s galleries during 2019. MAIN GALLERIES DRYDEN THEATRE MANSION Nathan Lyons: In Pursuit of Magic Abbas Kiarostami: 24 Frames 100 Years Ago: George Eastman in 1919 Curated by Lisa Hostetler, curator in charge, January 2–March 31, 2019 Curated by Jesse Peers, archivist, Department of Photography, and Jamie M. Allen, George Eastman Legacy Collection Stephen B. and Janice G. Ashley Associate Peter Bo Rappmund: Tectonics January 1–December 30, 2019 Curator, Department of Photography April 16–July, 6 2019 January 25–June 9, 2019 From the Camera Obscura to Lena Herzog: Last Whispers the Revolutionary Kodak The Art of Warner Bros.