Stellarium User Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Creating a Sonified Spacecraft Game Using Happybrackets and Stellarium

Proceedings of the 17th Linux Audio Conference (LAC-19), CCRMA, Stanford University, USA, March 23–26, 2019 CREATING A SONIFIED SPACECRAFT GAME USING HAPPYBRACKETS AND STELLARIUM Angelo Fraietta Ollie Bown UNSW Art and Design UNSW Art and Design University of New South Wales, Australia University of New South Wales, Australia [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT the field of view. For example, Figure 2 shows how the player might view Saturn from Earth, while Figure 3 shows how the player may This paper presents the development of a virtual spacecraft simula- view Saturn from their spacecraft. The sonic poi generates sound tor game, where the goal for the player is to navigate their way to that is indicative of the player’s field of view. Additionally, the poi various planetary or stellar objects in the sky with a sonified poi. provides audible feedback when the player zooms in or out. The project utilises various open source hardware and software plat- forms including Stellarium, Raspberry Pi, HappyBrackets and the Azul Zulu Java Virtual Machine. The resulting research could be used as a springboard for developing an interactive science game to facilitate the understanding of the cosmos for children. We will describe the challenges related to hardware, software and network integration and the strategies we employed to overcome them. 1. INTRODUCTION HappyBrackets is an open source Java based programming environ- ment for creative coding of multimedia systems using Internet of Things (IoT) technologies [1]. Although HappyBrackets has focused primarily on audio digital signal processing—including synthesis, sampling, granular sample playback, and a suite of basic effects–we Figure 2: Saturn viewed from the ground from Stellarium. -

Filter Performance Comparisons for Some Common Nebulae

Filter Performance Comparisons For Some Common Nebulae By Dave Knisely Light Pollution and various “nebula” filters have been around since the late 1970’s, and amateurs have been using them ever since to bring out detail (and even some objects) which were difficult to impossible to see before in modest apertures. When I started using them in the early 1980’s, specific information about which filter might work on a given object (or even whether certain filters were useful at all) was often hard to come by. Even those accounts that were available often had incomplete or inaccurate information. Getting some observational experience with the Lumicon line of filters helped, but there were still some unanswered questions. I wondered how the various filters would rank on- average against each other for a large number of objects, and whether there was a “best overall” filter. In particular, I also wondered if the much-maligned H-Beta filter was useful on more objects than the two or three targets most often mentioned in publications. In the summer of 1999, I decided to begin some more comprehensive observations to try and answer these questions and determine how to best use these filters overall. I formulated a basic survey covering a moderate number of emission and planetary nebulae to obtain some statistics on filter performance to try to address the following questions: 1. How do the various filter types compare as to what (on average) they show on a given nebula? 2. Is there one overall “best” nebula filter which will work on the largest number of objects? 3. -

Celestial Navigation (Fall) NAME GROUP

SIERRA COLLEGE OBSERVATIONAL ASTRONOMY LABORATORY EXERCISE Lab N03: Celestial Navigation (Fall) NAME GROUP OBJECTIVE: Learn about the Celestial Coordinate System. Learn about stellar designations. Learn about deep sky object designations. INTRODUCTION: The Horizon Coordinate System is simple, but flawed, because the altitude and azimuth measures of stars change as the sky rotates. Astronomers have developed an improved scheme called the Celestial Coordinate System, which is fixed with the stars. The two coordinates are Right Ascension and Declination. Declination ranges from the North Celestial Pole to the South Celestial Pole, with the Celestial Equator being a line around the sky at the midline of those two extremes. We will use these coordinates when navigating using the SC001 and SC002 charts. There are many ways to designate stars. The most common is called the Bayer designations. The Bayer designation of a star starts with a Greek letter. The brightest star in the constellation gets “alpha” (the first letter in the Greek alphabet), the second brightest star gets “beta,” and so on. (The Greek alphabet is shown below.) The Bayer designation must also include the constellation name. There are only 24 letters in the Greek alphabet, so this system is obviously very limited. The Greek alphabet 1) Alpha 7) Eta 13) Nu 19) Tau 2) Beta 8) Theta 14) Xi 20) Upsilon 3) Gamma 9) Iota 15) Omicron 21) Phi 4) Delta 10) Kappa 16) Pi 22) Chi 5) Epsilon 11) Lambda 17) Rho 23) Psi 6) Zeta 12) Mu 18) Sigma 24) Omega A more extensive naming system is called the Flamsteed designation. -

Successful Observing Sessions HOWL-EEN FUN Kepler’S Supernova Remnant Harvard’S Plate Project and Women Computers

Published by the Astronomical League Vol. 69, No. 4 September 2017 Successful Observing Sessions HOWL-EEN FUN Kepler’s Supernova Remnant Harvard’s Plate Project and Women Computers T HE ASTRONOMICAL LEAGUE 1 he 1,396th entry in John the way to HR 8281, is the Dreyer’s Index Catalogue of Elephant’s Trunk Nebula. The T Nebulae and Clusters of left (east) edge of the trunk Stars is associated with a DEEP-SKY OBJECTS contains bright, hot, young galactic star cluster contained stars, emission nebulae, within a large region of faint reflection nebulae, and dark nebulosity, and a smaller region THE ELEPHANT’S TRUNK NEBULA nebulae worth exploring with an within it called the Elephant’s 8-inch or larger telescope. Trunk Nebula. In general, this By Dr. James R. Dire, Kauai Educational Association for Science & Astronomy Other features that are an entire region is absolute must to referred to by the check out in IC pachyderm 1396 are the proboscis phrase. many dark IC 1396 resides nebulae. Probably in the constellation the best is Cepheus and is Barnard 161. This located 2,400 light- dark nebula is years from Earth. located 15 To find IC 1396, arcminutes north start at Alpha of SAO 33652. Cephei, a.k.a. The nebula Alderamin, and go measures 5 by 2.5 five degrees arcminutes in southeast to the size. The nebula is fourth-magnitude very dark. Myriad red star Mu Cephei. Milky Way stars Mu Cephei goes by surround the the Arabic name nebula, but none Erakis. It is also can be seen in called Herschel’s this small patch of Garnet Star, after the sky. -

Wynyard Planetarium & Observatory a Autumn Observing Notes

Wynyard Planetarium & Observatory A Autumn Observing Notes Wynyard Planetarium & Observatory PUBLIC OBSERVING – Autumn Tour of the Sky with the Naked Eye CASSIOPEIA Look for the ‘W’ 4 shape 3 Polaris URSA MINOR Notice how the constellations swing around Polaris during the night Pherkad Kochab Is Kochab orange compared 2 to Polaris? Pointers Is Dubhe Dubhe yellowish compared to Merak? 1 Merak THE PLOUGH Figure 1: Sketch of the northern sky in autumn. © Rob Peeling, CaDAS, 2007 version 1.2 Wynyard Planetarium & Observatory PUBLIC OBSERVING – Autumn North 1. On leaving the planetarium, turn around and look northwards over the roof of the building. Close to the horizon is a group of stars like the outline of a saucepan with the handle stretching to your left. This is the Plough (also called the Big Dipper) and is part of the constellation Ursa Major, the Great Bear. The two right-hand stars are called the Pointers. Can you tell that the higher of the two, Dubhe is slightly yellowish compared to the lower, Merak? Check with binoculars. Not all stars are white. The colour shows that Dubhe is cooler than Merak in the same way that red-hot is cooler than white- hot. 2. Use the Pointers to guide you upwards to the next bright star. This is Polaris, the Pole (or North) Star. Note that it is not the brightest star in the sky, a common misconception. Below and to the left are two prominent but fainter stars. These are Kochab and Pherkad, the Guardians of the Pole. Look carefully and you will notice that Kochab is slightly orange when compared to Polaris. -

Sphere, Sweet Sphere: Recycling to Make a New Planetarium Page 83

Online PDF: ISSN 23333-9063 Vol. 45, No. 3 September 2016 Journal of the International Planetarium Society Sphere, sweet sphere: Recycling to make a new planetarium Page 83 Domecasting_Ad_Q3.indd 1 7/20/2016 3:42:33 PM Executive Editor Sharon Shanks 484 Canterbury Ln Boardman, Ohio 44512 USA +1 330-783-9341 [email protected] September 2016 Webmaster Alan Gould Lawrence Hall of Science Planetarium Vol. 45 No. 3 University of California Berkeley CA 94720-5200 USA Articles [email protected] IPS Special Section Advertising Coordinator 8 Meet your candidates for office Dale Smith (See Publications Committee on page 3) 12 Honoring and recognizing the good works of Membership our members Manos Kitsonas Individual: $65 one year; $100 two years 14 Two new ways to get involved Institutional: $250 first year; $125 annual renewal Susan Reynolds Button Library Subscriptions: $50 one year; $90 two years All amounts in US currency 16 Vision2020 update and recommended action Direct membership requests and changes of Vision2020 Initiative Team address to the Treasurer/Membership Chairman Printed Back Issues of Planetarian 20 Factors influencing planetarium educator teaching IPS Back Publications Repository maintained by the Treasurer/Membership Chair methods at a science museum Beau Hartweg (See contact information on next page) 30 Characterizing fulldome planetarium projection systems Final Deadlines Lars Lindberg Christensen March: January 21 June: April 21 September: July 21 Eclipse Special Section: Get ready to chase the shadow in 2017 December: October 21 38 Short-term event, long-term results Ken Miller Associate Editors 42 A new generation to hook on eclipses Jay Ryan Book Reviews April S. -

A Guide to Free Desktop Planetarium Software Resources

Touring the Cosmos through Your Computer: A Guide to Free Desktop Planetarium Software Resources Matthew McCool Southern Polytechnic SU E-mail: [email protected] Summary Key Words This paper reviews ten free software applications for viewing the cosmos Open source astronomy through your computer. Although commercial astronomy software such as Astronomy software Starry Night and Slooh make for excellent viewing of the heavens, they come Digital universes at a price. Fortunately, there is astronomy software that is not only excellent but also free. In this article I provide a brief overview of ten popular free Desktop Planetarium software programs available for your desktop computer. Astronomy Software Table 1. Ten free desktop planetarium applications. Software Computer Platform Web Address Significant strides have been made in free Asynx Windows 2000, XP, NT www.asynx-planetarium.com Desktop Planetarium software for modern commercial computers. Applications range Celestia Linux x86, Mac OS X, Windows www.shatters.net/celestia from the simple to the complex. Many of Deepsky Free Windows 95/98/Me/XP/2000/NT www.download.com/Deepsky- Free/3000-2054_4-10407765.html these astronomy applications can run on several computer platforms (Table 1). DeskNite Windows 95/98/Me/XP/2000/NT www.download.com/DeskNite/ 3000-2336_4-10030582.html Digital Universe Irix, Linux, Mac OS X, Windows www.haydenplanetarium.org/ Most amateur astronomers can meet their universe/download celestial needs using one or more of these Google Earth Linux, Mac OS X, Windows http://earth.google.com/ applications. While applications such as MHX Astronomy Helper Windows Me/XP/98/2000 www.download.com/MHX- Stellarium and Celestia provide a more or Astronomy-Helper/ less comprehensive portal to the heavens, 3000-2054_4-10625264.html more specialised programs such as Solar Solar System 3D Simulator Windows Me/XP/98/2000/NT www.download.com/ System 3D Simulator provide narrow, but Solar-System-3D-Simulator/ focused functionality. -

Stellarium User Guide

Stellarium User Guide Matthew Gates 25th January 2008 Copyright c 2008 Matthew Gates. Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sec- tions, no Front-Cover Texts, and no Back-Cover Texts. A copy of the license is included in the section entitled "GNU Free Documentation License". 1 Contents 1 Introduction 6 2 Installation 7 2.1 SystemRequirements............................. 7 2.2 Downloading ................................. 7 2.3 Installation .................................. 7 2.3.1 Windows ............................... 7 2.3.2 MacOSX............................... 7 2.3.3 Linux................................. 8 2.4 RunningStellarium .............................. 8 3 Interface Guide 9 3.1 Tour...................................... 9 3.1.1 TimeTravel.............................. 10 3.1.2 MovingAroundtheSky . 10 3.1.3 MainTool-bar ............................ 11 3.1.4 TheObjectSearchWindow . 13 3.1.5 HelpWindow............................. 14 3.1.6 InformationWindow . 14 3.1.7 TheTextMenu ............................ 15 3.1.8 OtherKeyboardCommands . 15 4 Configuration 17 4.1 SettingtheDateandTime .. .... .... ... .... .... .... 17 4.2 SettingYourLocation. 17 4.3 SettingtheLandscapeGraphics. ... 19 4.4 VideoModeSettings ............................. 20 4.5 RenderingOptions .............................. 21 4.6 LanguageSettings............................... 21 -

Physical Processes in the Interstellar Medium

Physical Processes in the Interstellar Medium Ralf S. Klessen and Simon C. O. Glover Abstract Interstellar space is filled with a dilute mixture of charged particles, atoms, molecules and dust grains, called the interstellar medium (ISM). Understand- ing its physical properties and dynamical behavior is of pivotal importance to many areas of astronomy and astrophysics. Galaxy formation and evolu- tion, the formation of stars, cosmic nucleosynthesis, the origin of large com- plex, prebiotic molecules and the abundance, structure and growth of dust grains which constitute the fundamental building blocks of planets, all these processes are intimately coupled to the physics of the interstellar medium. However, despite its importance, its structure and evolution is still not fully understood. Observations reveal that the interstellar medium is highly tur- bulent, consists of different chemical phases, and is characterized by complex structure on all resolvable spatial and temporal scales. Our current numerical and theoretical models describe it as a strongly coupled system that is far from equilibrium and where the different components are intricately linked to- gether by complex feedback loops. Describing the interstellar medium is truly a multi-scale and multi-physics problem. In these lecture notes we introduce the microphysics necessary to better understand the interstellar medium. We review the relations between large-scale and small-scale dynamics, we con- sider turbulence as one of the key drivers of galactic evolution, and we review the physical processes that lead to the formation of dense molecular clouds and that govern stellar birth in their interior. Universität Heidelberg, Zentrum für Astronomie, Institut für Theoretische Astrophysik, Albert-Ueberle-Straße 2, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany e-mail: [email protected], [email protected] 1 Contents Physical Processes in the Interstellar Medium ............... -

Stellarium for Cultural Astronomy Research

RESEARCH The Simulated Sky: Stellarium for Cultural Astronomy Research Georg Zotti Ludwig Boltzmann Institute for Archaeological Prospection and Virtual Archaeology, Vienna, Austria [email protected] Susanne M. Hoffmann Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena, Michael-Stifel-Center/ Institut für Informatik and Physikalisch- Astronomische Fakultät, Jena, Germany [email protected] Alexander Wolf Altai State Pedagogical University, Barnaul, Russia [email protected] Fabien Chéreau Stellarium Labs, Toulouse, France [email protected] Guillaume Chéreau Noctua Software, Hong Kong [email protected] Abstract: For centuries, the rich nocturnal environment of the starry sky could be modelled only by analogue tools such as paper planispheres, atlases, globes and numerical tables. The immer- sive sky simulator of the twentieth century, the optomechanical planetarium, provided new ways for representing and teaching about the sky, but the high construction and running costs meant that they have not become common. However, in recent decades, “desktop planetarium programs” running on personal computers have gained wide attention. Modern incarnations are immensely versatile tools, mostly targeted towards the community of amateur astronomers and for knowledge transfer in transdisciplinary research. Cultural astronomers also value the possibili- ties they give of simulating the skies of past times or other cultures. With this paper, we provide JSA 6.2 (2020) 221–258 ISSN (print) 2055-348X https://doi.org/10.1558/jsa.17822 ISSN (online) 2055-3498 222 Georg Zotti et al. an extended presentation of the open-source project Stellarium, which in the last few years has been enriched with capabilities for cultural astronomy research not found in similar, commercial alternatives. -

May / June 2010 Amateur Astronomy Club Issue 93.1/94.1 29°39’ North, 82°21’ West

North Central Florida’s May / June 2010 Amateur Astronomy Club Issue 93.1/94.1 29°39’ North, 82°21’ West Member Member Astronomical International League Dark-Sky Association NASA Early Morning Launch of Discovery STS-131 Provides Quite a Show! Photo Below: Taken in Titusville on SR 406 / 402 Causeway by Mike Lewis. The camera is a Nikon D2X with Nikon 400mm / f2.8 lens on automatic exposure (f8 @ 1/250s). “First night launch I’ve made it to in a while, and it was great.” - Mike Lewis Photo Below: Time-lapse photo by Howard Cohen taken from SW Gainesville (190 sec- onds long, beginning 6:22:52 a.m. EDT). “I like others was struck by the comet-like contrail that eventually followed the shuttle as it gained altitude.” - Howard Cohen Newberry Sports Complex and Observatory Rich Russin The President’s Corner As we head to press, work continues towards the establishment of an agree- ment between the AAC, the NSC, and the City of Newberry that would establish a permanent observing site on the grounds of the Newberry Sports Complex. The outcome will almost certainly be known before the next newsletter. For those of you not familiar with the project, the club has been offered an op- portunity to establish a base for both club and outreach events. Part of the pro- posal includes a permanent observing site, onsite storage, and possibly an ob- servatory down the road. In return, the club will provide an agreed upon number of outreach events and astronomy related support for the local school science programs. -

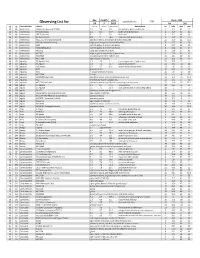

Observing List

day month year Epoch 2000 local clock time: 2.00 Observing List for 24 7 2019 RA DEC alt az Constellation object mag A mag B Separation description hr min deg min 39 64 Andromeda Gamma Andromedae (*266) 2.3 5.5 9.8 yellow & blue green double star 2 3.9 42 19 51 85 Andromeda Pi Andromedae 4.4 8.6 35.9 bright white & faint blue 0 36.9 33 43 51 66 Andromeda STF 79 (Struve) 6 7 7.8 bluish pair 1 0.1 44 42 36 67 Andromeda 59 Andromedae 6.5 7 16.6 neat pair, both greenish blue 2 10.9 39 2 67 77 Andromeda NGC 7662 (The Blue Snowball) planetary nebula, fairly bright & slightly elongated 23 25.9 42 32.1 53 73 Andromeda M31 (Andromeda Galaxy) large sprial arm galaxy like the Milky Way 0 42.7 41 16 53 74 Andromeda M32 satellite galaxy of Andromeda Galaxy 0 42.7 40 52 53 72 Andromeda M110 (NGC205) satellite galaxy of Andromeda Galaxy 0 40.4 41 41 38 70 Andromeda NGC752 large open cluster of 60 stars 1 57.8 37 41 36 62 Andromeda NGC891 edge on galaxy, needle-like in appearance 2 22.6 42 21 67 81 Andromeda NGC7640 elongated galaxy with mottled halo 23 22.1 40 51 66 60 Andromeda NGC7686 open cluster of 20 stars 23 30.2 49 8 46 155 Aquarius 55 Aquarii, Zeta 4.3 4.5 2.1 close, elegant pair of yellow stars 22 28.8 0 -1 29 147 Aquarius 94 Aquarii 5.3 7.3 12.7 pale rose & emerald 23 19.1 -13 28 21 143 Aquarius 107 Aquarii 5.7 6.7 6.6 yellow-white & bluish-white 23 46 -18 41 36 188 Aquarius M72 globular cluster 20 53.5 -12 32 36 187 Aquarius M73 Y-shaped asterism of 4 stars 20 59 -12 38 33 145 Aquarius NGC7606 Galaxy 23 19.1 -8 29 37 185 Aquarius NGC7009